By Christopher Miskimon

A British squadron lay wrecked on the waters of Lake Erie. Six vessels of war floated in ruins and 135 English sailors lay dead or wounded. While smoke still rose above the shot-riddled hulks, the American commander, Oliver Hazard Perry, composed his now-famous message: “We have met the enemy and they are ours.” With the utterance of these words, Lake Erie became de facto American waters, and U.S. soldiers on land were free to resume their advance against the British forces on the northwestern frontier. That advance would culminate in the Battle of the Thames.

To this point, the War of 1812 had proven a very mixed adventure for the Americans. There had been a number of surprisingly successful engagements at sea, where the small but aggressive U.S. Navy had bested the Royal Navy in several ship-to-ship battles. While these victories had little impact on the overall war, they were well-publicized morale boosters. On land, however, the tiny American army, bolstered by thousands of militia, faced a much more difficult struggle. Several invasions of Canada, both in the east and west, had failed miserably. Militia troops were poorly organized and often refused outright to serve outside American borders. Much of the militia’s leadership was composed of political appointees, often of dubious military quality.

Such problems affected American forces in the Northwest Territory, where animosity ran high against both the indigenous Native American tribes and the British rulers of Canada. The Indians were natural enemies of the Americans in a bitter, ongoing struggle over land and resources that had lasted for centuries. In concert, anger at the British ran high as well; Great Britain desired to check American expansion westward, allying itself with local tribes and providing them with arms and supplies to be used against American settlers. For several years the Shawnee leader Tecumseh, along with his brother Tenskwatawa, also known as “the Prophet,” had sought to unite the disparate tribes in a multitribal confederacy that could better resist white migration. With the onset of the second war between the United States and Great Britain, Tecumseh threw in his lot with the British.

“Remember the Raisin”

American efforts in the Northwest had started with an invasion of Upper Canada by William Hull, governor of Michigan Territory, in July 1812. This offensive failed miserably, resulting in Detroit falling into British hands. In January 1813, an American force was defeated at Frenchtown, Michigan, with most of the force taken prisoner after Brig. Gen. James Winchester surrendered his men to British Colonel Henry Proctor. When Proctor withdrew, he callously or carelessly left behind some of his Indian allies to guard the wounded prisoners. Depending on accounts, between 30 and 60 of the wounded Americans were killed by the Indians. When this was reported in the American press as the “Raisin River Massacre,” outrage spread across the nation and “Remember the Raisin!” became a western battle cry.

Hull’s replacement, William Henry Harrison, was at the time the governor of Indiana Territory. Harrison had achieved national fame for his part in the Battle of Tippecanoe on November 7, 1811, and was popular in the West. When Hull surrendered Detroit, a replacement was needed and western politicians, particularly Kentuckians, lobbied hard for Harrison to be appointed commander, even though Winchester, who held a regular army commission, was preferred in Washington (this was before Winchester’s defeat at Frenchtown). The Kentuckians even went so far as to make Harrison a major general of the Kentucky militia so that he would outrank Winchester, despite the fact that he was serving as governor of a different territory at the time. On September 17, 1812, the administration of President James Madison gave Harrison command of all forces in the Northwest.

By the time Harrison received word of his promotion it was too late in the year to begin campaigning, so instead he occupied his troops by launching raids against hostile Indians and building fortifications to resist British assaults. Efforts to resume the offensive were further hampered when, in March 1813, U.S. Secretary of War James Armstrong ordered Harrison to take a strictly defensive posture. Besides demonstrating a notable lack of faith in the western governor, Armstrong had been advised that the American treasury was too empty to fund operations on that front.

Victory on Lake Erie

With the arrival of spring, Harrison’s fortifications were put to the test. With Lake Erie still under British control, Proctor resumed his offensive. Accompanied by his ally Tecumseh, he returned to American soil to launch attacks against Fort Meigs in May and Fort Stephenson in July. Both attacks were repulsed by the Americans. At Fort Meigs, a counterattack by Kentucky militia under General Green Clay drove the British back at great loss. At Fort Stephenson, Kentucky marksmen and a stiff defense likewise denied the British victory.

Tensions arose during both operations between the British and their Indian allies. Once again, prisoners were executed by the Indians despite Tecumseh’s alleged attempt to stop them, and there was the constant problem of native warriors deserting the army. While these things infuriated Proctor, Indian cultural rules of warfare did not require an individual to remain with a war party any longer than he chose to do so. After the unsuccessful engagements, Proctor returned to the Canadian side of the border at Fort Malden, near Amherstburg.

Along with these battles, Harrison kept himself occupied, moving frequently to Cleveland to coordinate with Commodore Perry. Eager to see Perry gain control of Lake Erie, Harrison even loaned the young seaman some of his troops to fill out the crews on his small squadron of warships. So far inland, experienced sailors were in critically short supply.

The critical battle for Lake Erie took place on September 10, 1813. Perry’s squadron of nine warships, four of them small gunboats, faced off against a British force of six vessels under Commander Robert Barclay of the Royal Navy. Action commenced at 10:45 am and continued until 3 pm, by which time four of the British ships had struck their colors in surrender. Their remaining vessels attempted to flee but were quickly run down by the Americans. It had been a sharp, intense engagement; 68 were killed and 190 wounded on both sides, but the result was American control of Lake Erie.

Harrison and Perry on the Offensive

With the American naval victory, Proctor decided that his position at Fort Malden was untenable and began to withdraw northward toward the town of Sandwich. Tecumseh and his Indian allies were upset; to them, a British retreat was tantamount to abandonment, but Proctor had no real choice. He was badly outnumbered, even though the American army was mostly militia. Fort Malden was practically devoid of provisions, and with the elimination of the British naval squadron, resupply was out of the question.

Control of Lake Erie meant the American army was also on the move. Harrison sent out a call for militia from the nearby states and territories. Troops poured in until there were perhaps 6,000 men under arms, the largest contingent arriving from Kentucky under their governor, Isaac Shelby, a 63-year-old veteran of the Revolutionary War Battle of Kings Mountain. Many of the troops were mounted, although only Congressman Richard Johnson’s regiment took its own horses along; the rest were left behind in a large corral that Harrison had built.

Perry was eager to help Harrison exploit the hard-won naval battle, using his ships to transport soldiers for the pursuit of Proctor and Tecumseh. To facilitate this cooperation, over the previous winter and spring Harrison had ordered the construction of some 90 bateaux (flat-bottomed boats commonly used on the local rivers) in Cleveland. The army moved first to Camp Portage in Ohio, then relayed to South Bass Island and finally to Middle Sister Island, closer to Amherstburg. As the Americans closed in, Proctor burned both Fort Malden and the Amherstburg Navy Yard and sought to preserve his dwindling force, between 700 and 900 Englishmen. They left ingloriously, carrying as many of their provisions with them as they could.

After reaching Sandwich, the British-Indian force turned eastward, following the southern shore of Lake St. Clair to the mouth of the Thames River. Crossing over to the river’s north bank, they continued eastward, following the river. The retreat was pitiful to see. The British had to dispose of much of their supplies as they went, often simply dumping them into the river. Each day the force grew smaller as Indian warriors, discouraged by the withdrawal, melted away into the surrounding woods in large numbers. Making things worse, frequent rains soaked the already demoralized troops. Families and camp followers straggled behind, preventing the British from destroying the bridges the Americans must use to pursue them. To assuage Tecumseh, Proctor promised to make a stand upriver at a point near Chatham, Ontario. However, neither of them knew the area very well, and plans were inchoate at best.

Behind them, Harrison’s army landed near Amherstburg on September 27 and quickly took up the chase. He detached most of his regulars to garrison Fort Detroit, Sandwich, and a temporary position named Fort Covington, near the ruins of Fort Malden, before moving on with a force of 3,500 men, the bulk of them Kentucky militia. The mounted Kentuckians were under the command of Colonel Richard M. Johnson, whose brother James served as lieutenant colonel. Perry’s ships shadowed the force on shore, moving alongside them. Upon reaching the River Thames, only three of his gunboats, Scorpion, Porcupine, and Tigris, could clear the bar at its entrance; the rest were too large. Perry continued on with the ships until he turned command over to fellow naval officer Jesse Elliot. Eager to join the impending fight, Perry had gone ashore as a volunteer aide to General Harrison.

Finding Favorable Terrain

As his men marched east, Proctor spent most of his time riding ahead of the main column, ostensibly on reconnaissance of the army’s route, his family accompanying him. This would later open his conduct to accusations of cowardice and poor leadership. On October 3, upon reaching the point where he had promised to make a stand with Tecumseh, Proctor decided that the terrain was unfavorable and ordered his troops to continue marching. Nevertheless, the Indian leader gathered some of his warriors, whose total number had dwindled to around 600, along with a small British detachment and laid an ambush for the approaching Americans. Unfortunately for Tecumseh, Harrison was warned about the surprise attack by sympathetic locals. He sent up two six-pounder field guns and opened fire on the hiding enemy. Having lost the vital element of surprise, the dejected Indians and British fell back and rejoined the main column.

Meanwhile, Proctor returned from his reconnaissance and led his army toward Moraviantown, a Christian Indian village he had purchased as winter quarters for his troops. The sick and wounded were moved there ahead of the remaining fit men, now numbering around 450, most of them from the 41st Regiment of Foot. By October 5, Harrison’s horsemen were hot on the heels of their foe. That morning the boats carrying the British reserve ammunition were captured. The advancing Americans had been finding discarded supplies for days. The battle would be joined two miles west of Moraviantown.

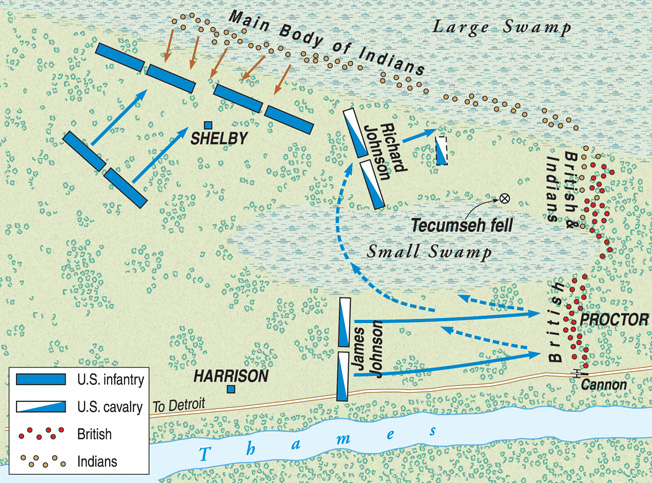

Proctor had at last found a position whose terrain was more favorable to defense, a wedge-shaped clearing in the thick, swampy forests. He placed his regulars at the narrow end of the wedge, between the river on his left and a large wooded swamp on the right. Along the river between it and the Detroit road was a tangle of thick brush that helped secure their left flank. The right flank was secured by the swamp itself, known as the Backmetack Marsh, too thick for horsemen to traverse and difficult even for infantry.

The British soldiers formed a line 300 yards long between the two natural obstacles. The ground in front of their line had another patch of boggy swampland in the middle, forcing any attacker to split his force. Just inside the swamp on the British right, Tecumseh and his warriors took up positions in place to outflank the Americans as they approached the British line. Proctor placed one six-pounder cannon on the road itself. With the flanks secure and terrain that would channel their opponents into a frontal attack, the British had a fairly good defensive position from which to fight. Also, their opponents were almost completely militia, whose reputation against regulars was mixed at best. Still, the question remained whether the British had the numbers to repulse a determined American assault. Exhaustion and hunger further hampered the English force.

Breaking the British Lines

When Harrison and his army arrived shortly after noon, he wondered himself about the prospects of charging British regulars across such unfavorable terrain. Colonel Johnson rode up and requested permission to personally charge the British line with his regiment of mounted Kentucky volunteers. Harrison refused, fearful of the casualties such a charge might sustain against closed ranks of well-drilled enemy regulars. Instead, he ordered Major Eleazar Wood to perform a reconnaissance of Proctor’s lines.

Wood’s observations changed Harrison’s mind. The major had discovered that the British, instead of aligning themselves in the standard close-order formations of the day, were spread out in open order, alone or in small groups, using trees for cover. Proctor had dispersed his men in this way at the urging of Tecumseh, who advised that fighting in such terrain required a more native arrangement. While such a formation was suited to the Indian style of warfare, it unfortunately served to disperse the firepower of the British muskets and isolated the Redcoats from each other. It was a flaw that Harrison quickly noted and decided to exploit.

With the British unable to mass their firepower, the American general gave permission for Johnson to lead his cavalry against them. His regiment’s strength was some 950 troops in 12 companies, divided equally into two battalions. One would advance along the right side of the field against the British left, while the other would move against the mixed force of Indians and regulars on the enemy right. Johnson considered the mixed group the more dangerous of the two and took personal command of the battalion facing them. He gave the other battalion to his brother James. Most of the militia infantry formed on the American left facing Backmetack Marsh, commanded by Governor Shelby.

By the time all was ready, it was after 3 pm. American skirmishers moved forward and exchanged fire with the British, then the cavalry charged, shouting the war cry: “Remember the Raisin!” On the right, James Johnson led his horsemen galloping into the British line. Scattered musket fire met them but did nothing to slow the Americans’ momentum. Within seconds, the riders pierced the ragged British line, breaking through and then turning to attack their enemy from the rear. Confusion reigned; British troops began to break and flee. A private from the 41st Foot, Shadrach Byfield, later wrote of the chaos: “After exchanging a few shots, our men gave way. I was in the act of retreating when one of our sergeants exclaimed ‘For God’s sake, men, stand and fight.’ I stood by him and fired one shot, but the line was broken and the men were retreating.”

The British troops were suddenly and shockingly defeated. The majority of them were taken prisoner by James Johnson’s cavalry, which had suffered only three wounded in their charge. British casualties, not counting prisoners, were also relatively light: 12 dead and 22 wounded. Their single six-pounder gun had been overrun without firing a shot; either its crew had been too surprised by the charge to fire, or perhaps its ammunition had been ruined by the rain or lost during the earlier retreat. At some point during the rout, Proctor himself retreated northeast toward Moraviantown with those few regulars who had avoided capture. James Johnson turned his cavalry north and rode quickly to assist his brother against Tecumseh and his warriors.

The Death of Tecumseh

On the American left, Richard Johnson used an old frontier trick against the Indians. A group of 20 volunteers agreed to charge ahead of the main body. With luck, the natives would empty their muskets at them, allowing the rest to approach in relative safety. These men galloped toward the warriors, taking cover in the swampy woods ahead. The ruse worked. Gunfire erupted from the trees, concentrating on the leading horsemen. Casualties were high—fully 75 percent of the 20 Americans were either killed or wounded. The rest of the Kentucky horsemen rode directly toward the tree line unopposed.

Once there, however, they began to encounter difficulty. Inside the marsh the ground was soft and covered in thick brush that formed a natural abatis, preventing the cavalrymen from entering on horseback. Richard Johnson ordered them to dismount and fight on foot. Pressed heavily, Tecumseh’s men began to fall back slowly, their own flank left uncovered by the rout of the British. Farther down the Indian line where the militia infantry had moved up near the Indian right, the warriors noticed that the Kentuckians appeared reluctant to advance any closer. The warriors decided to attack, hoping to push back the seemingly hesitant white men. Charging out from the swamp, they quickly formed a wedge between two of the militia brigades, which began to fall back.

Harrison saw what was happening and acted quickly, restoring the American lines by sending in a fresh regiment of Kentucky troops, assisted by Shelby and Oliver Hazard Perry. It was too much for the Indians, who fell back to their former positions in the swamp.

Now came a critical moment in the battle. Richard Johnson was still astride his horse despite having suffered four separate wounds; his hapless mount was itself wounded seven times. The colonel had stayed in the saddle to more easily direct his dismounted troops, but it made him a tempting target. Now a solitary Indian chief charged at him, firing a shot that hit Johnson in the hand. When he still kept in his saddle, the Indian drew his tomahawk and charged. Despite the injury to his hand, and with his opponent drawing quickly closer, Johnson managed to draw his pistol and fire a load of buck and ball (one musket ball and three smaller buckshot) at the onrushing Indian. The attacker was struck in the chest and fell to the ground, dead.

Claims later arose (although not from Johnson) that the slain Indian was Tecumseh, who was killed during the battle. However, given the chaotic nature of the battle, no one was certain who had killed the chief. Richard Johnson, wounded and fighting for his life, would likely not have known who was attacking him and in fact never claimed overtly that he was Tecumseh’s killer. He was often credited with the feat anyway, and while he never claimed it, neither did he particularly deny it. Whatever the truth, Tecumseh was indeed dead, and his loss sapped the warriors’ will to continue the fight. They quickly retreated into the swamps and woods, leaving the field to the exultant Americans. The battle was effectively over.

A Stunning Strategic Victory at the Battle of the Thames

Considering the strategic significance of the Battle of the Thames, overall casualties were light. The fight against Tecumseh’s warriors had cost the Americans seven dead and 19 wounded, while Harrison counted 33 dead Indians on the field, with an additional unknown number of dead and wounded carried off by their comrades. Total British casualties including prisoners rose to over 600 for the entire campaign. Tecumseh’s body was dismembered and made into souvenirs for the victorious Americans, a sign of the essential bitterness and hatred that permeated conflict between the frontiersmen and the Native Americans. “Tecumseh razor strops,” as they were known, were brandished with relish across the frontier. Many other Indian bodies were also mutilated after the battle. It is entirely possible that Tecumseh’s remains were carried off by some of his warriors and that some other hapless participant was torn apart in his place. A few of the frontier troops respected the slain leader. Charles Sherman, an Ohio militia officer, thought enough of the Indian to name his third son William Tecumseh Sherman, the future general of Civil War fame.

These relatively low casualty numbers belied the importance of the American victory. Combined with the defeat on Lake Erie, British operations in Upper Canada were effectively over. With Lower (Eastern) Canada under imminent threat of invasion by American forces from New York, the British could not spare men or supplies for a counteroffensive. Parts of Upper Canada would remain under American occupation until the Treaty of Ghent ended the war with the restoration of prewar lines in December 1814. For his part, Proctor was court-martialed and censured for his abject failure. His rank and pay were suspended for six months, although the Prince Regent later reduced the general’s punishment to a public reprimand—which was bad enough. Proctor returned to England, his career over, and died in obscurity in 1822.

For the Native American Confederacy, the Battle of the Thames was an utter and total disaster. Tecumseh, the one leader who had been able to unite the disparate tribes, was dead. Several of the tribes were so dismayed by the defeat that they made peace with Harrison later in the month. Their alliance with Britain was over, and the Northwest Territory was henceforth American. Indian hopes of retaining their land and British designs for an Indian buffer state had both been dashed in a single brief encounter in the swamp.

“Old Tippecanoe”: The Shortest Serving President

The battle had far-ranging implications for the Americans as well. Besides the elimination of an organized Native American block to eventual expansion, the battle was the first significant land victory for American forces during the war. It provided a vital boost to flagging morale and made the political careers of a number of participants. While Harrison was dogged by political enemies and virtually sat out the rest of the war, the battle enhanced his reputation and helped in his successful bid for the presidency in 1840. After a remarkable election underscored by the improbable reinvention of Harrison as “Old Tippecanoe,” a humble farmer, the Whig Party managed to capture the White House for Harrison. Tragically, Harrison became ill during his first month in office and died on April 4, 1841—exactly one month after taking office. Harrison’s tenure remains by far the shortest presidency in American history.

Similarly, Richard Johnson prospered politically, serving as vice president to the man Harrison defeated in 1840, Democratic President Martin Van Buren. Accounts, some greatly exaggerated, of his fight on the Thames figured prominently in Johnson’s campaign. Beyond these two leaders, three future governors, three lieutenant governors, four senators, and 20 congressmen could later claim to have been at the Battle of the Thames, making it one of the most politically decisive engagements in the course of American history, and one of the nation’s few shining moments in the controversial and little understood War of 1812.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments