By John Walker

At 11:02 am on August 9, 1945, an American warplane dropped an atomic device nicknamed “Fat Man” onto the city of Nagasaki, Japan. The bomb, generating the explosive power of 22,000 tons of TNT, killed at least 30,000 people instantly. It was the second of two atomic bombs dropped in three days’ time on Japan by an American government intent on forcing the aggressor nation’s unconditional surrender and hastening an end to World War II. But it was also the day that the Soviet invasion of Manchuria officially began.

Since the previous midnight, Soviet armies numbering over a million men, backed by armored, air, and naval forces, had begun sweeping into Manchuria—the Japanese puppet state on the East Asian mainland that the occupiers called Manchukuo—in what would be the last great military operation of World War II. The Soviet assault, a classic double-pincer movement with attacks from the west, north, and east, extended across water and land fronts some 2,730 miles from the Mongolian desert to the densely forested coast of the Sea of Japan. (You can read more about the Soviet Union’s involvement in the Second World War, including the bitter fighting across the Eastern Front, inside the pages of WWII History magazine.)

“The Scale of These Attacks is Not Large”

After bewildered Japanese units on the Manchurian border were hit with heavy shelling and massive ground assaults in the early morning hours of August 9, Japan’s Imperial headquarters issued an emergency announcement reporting that the Soviet Union had declared war on Japan and had begun entering Manchurian territory, but added absurdly, “The scale of these attacks is not large.” In reality, the first elements of a 1.5-million-man Soviet host, backed by small cavalry units of its ally, Outer Mongolia, were already in motion. Infantry, tank, horse cavalry, and mounted infantry, supported by river flotillas, air fleets, and 4,300 Soviet planes, would commence the invasion by striking Japanese convoys and cities in Manchuria and North Korea.

The Soviet Pacific Fleet stood ready to carry the invasion to the islands north of Japan—Sakhalin and the Kurils—which czarist Russia had lost to the Japanese 40 years earlier, along with the lease to the strategic warm-water port of Port Arthur, at the end of the Russo-Japanese War in 1905. For Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, the time had come to gather as much Asian booty as possible, while also erasing some of the stain remaining from the devastating, unexpected 1905 defeat—the first time an emerging Asian power had defeated a European power in the modern era.

As Nazi Germany’s continuing conquests in Europe threatened to spread the war to other continents and turn the conflict into another true global war, the Japanese and Russians in April 1941 concluded a five-year neutrality pact that served the interests of both nations well. Japan’s expansionist ambitions lay to the south and east, and it needed to guard against a threat from the rear. Russia, even before Japan found itself in a life-and-death struggle along with Nazi Germany, desired no complications in Asia. When the Germans invaded Russia in June 1941, Stalin, assured his eastern flank was secure, safely threw all his resources into the war in the West. Indeed, until August 8, 1945, Soviet neutrality in the East was so scrupulously preserved that American B-29 bombers that force-landed on Russian territory during raids on Japan had to remain there.

The Strangulation of Japan by American Blockade

Although peace on the Russian-Manchurian border continued to suit the two neighbors well, by 1944 it no longer suited the United States. There were more than a million Japanese soldiers in Manchuria and eastern China who could be redeployed against the Allies at any time. An invasion of Manchuria by the Russians was the obvious means of deflecting such a threat. In December 1944, after almost three years of massive efforts by the United States, including the employment of a quarter-million Americans on the Asian mainland supplying and advising Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Army in its futile operations against the Japanese, U.S. commanders concluded that Japan’s forces in Asia could not be defeated by the Chinese.

Neither Chiang’s Kuomintang Army, nor Mao Zedong’s Communist guerrilla forces mounted even the most minimal opposition to Japanese occupiers. Both organizations were clearly more interested in what would happen after the war ended and the Japanese were driven from the Asian mainland. Washington therefore turned to the only other power capable of defeating the Japanese—the Soviet Union. Throughout the winter of 1944-1945, with increasing urgency, Washington solicited Russian participation in the war against Japan. American field commanders wanted all the help they could get to diminish the numbers of Japanese they would have to confront in the climactic battles in the Pacific Theater. Great Britain’s prime minister, Winston Churchill, and American President Franklin D. Roosevelt were heartened by Stalin’s promise to launch 60 Soviet divisions against Japan within three months of Germany’s collapse.

Washington realized that the Russians wouldn’t fight unless they received tangible rewards for doing so. To destroy the Nazis, the Soviets had already contributed 25 times the human sacrifice made by all the other Allies combined. At a conference at Yalta in early February 1945, Stalin presented his demands for an eastern commitment: the Kuril Islands (a mostly uninhabited chain that ran from Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula to the northernmost tip of the Japanese home island of Hokkaido), southern Sakhalin Island, the lease of Port Arthur, access to Dalian as a free port, control of the southern Manchurian railway, and recognition of Soviet suzerainty over Outer Mongolia. On February 8, the fifth day at Yalta, Roosevelt agreed to Stalin’s terms; by doing so, he made important Chinese territorial commitments without first consulting the Chinese. The agreements were nominally subject to Chiang Kai-shek’s endorsement, in return for which Moscow pledged to recognize the Nationalists as China’s sole legitimate rulers.

By June 1945, after a three-month bloodbath secured the island of Okinawa—the final stepping-stone to a land invasion of Japan—American commanders welcomed any alternative that would avert the necessity of a ground assault. The prospect of using atomic weapons against the Japanese didn’t yet loom in their minds; their hopes of achieving victory without launching an amphibious invasion of Japan rested upon blockade, incendiary aerial bombardment, and Russian entry into the war. In the weeks to come, the successful testing of an atomic weapon on July 16 made the new American president, Harry Truman, far less enthusiastic about Russian intervention and expansionism in Asia.

Japan was slowly being strangled by an economic blockade that had brought her war-making capacity almost to a halt. In addition, beginning with the horrific firebombing of Tokyo on March 9, General Curtis LeMay’s conventional bomber force was in the process of virtually destroying Japan. B-29 bombers flying from the Mariana Islands had already leveled most of Japan’s major cities, killing some 200,000 civilians. By mid-1945, all these factors rendered an Allied invasion of the Japanese mainland increasingly unnecessary, and to some American political leaders the Soviet invasion of Manchuria seemed superfluous. Stalin had his own agenda, however, and Soviet participation in the Far East, agreed upon at Yalta, was at the top of his list.

The Soviet Far East Command

Their initial response to the August 9 invasion showed once again that the Japanese were either grossly unaware, or simply refused to accept, the direness of their predicament. Even those in Tokyo who had accepted that Stalin was “waiting for the ripe persimmon to fall,” and who had been repeatedly warned of Soviet troop movements eastward, had concluded that the Russians wouldn’t be ready to attack in Manchuria until autumn or the spring of 1946.

Inside Manchuria, Japan’s Kwangtung Army, commanded by General Otozo Yamada, was nowhere near operational readiness; its best units had been sent to Okinawa and Kyushu months earlier. Few demolition charges had been laid, air support was negligible, and some senior commanders were absent from their posts. In the early months of 1945, tens of thousands of refugees from the Japanese home islands had moved to Manchuria with all their possessions, believing the colony to be a safe haven. Incredibly, no steps were taken to evacuate these Japanese civilians, on the grounds that such precautions would promote defeatism. Stalin’s objective was massive territorial gain, and he was prepared to pay heavily for it. For the Manchurian invasion, the Soviets made medical provisions for 540,000 casualties, including 160,000 dead (a forecast predicated on an assessment of Japan’s paper strength). Stalin had for years maintained 40 divisions on the Manchurian border, and in the spring of 1945 he doubled his forces there. Between May and June, some 3,000 locomotives labored tirelessly along the Trans-Siberian rail link, transferring an additional 40 Soviet divisions on a month-long journey eastward to the Mongolian and Manchurian borders.

After traveling 6,000 miles from Europe by rail, Soviet units marched the last 200 miles to the Manchurian border across the treeless Mongolian desert in blazing heat. As part of Stalin’s agreement with the Allies, the United States helped feed and arm the Soviet host; some 500 new Sherman tanks were offloaded at Russian ports. As Russian troops approached the frontier, elaborate camouflage and deception schemes were adopted; senior Soviet officers traveled under false names and didn’t wear rank insignia. The 6th Guards Tank Army left all its tanks, self-propelled artillery, and vehicles in Czechoslovakia, picking up new equipment manufactured by the Soviet Ural factories.

For the first time in the war, the Soviets created a full-fledged separate theater of operations. The Soviet Far East Command’s plan, implemented by its commander, Marshal Aleksandr Vasilevsky, was simple but massive, calling for envelopment of the Japanese defenses on three axes, followed by the capture of Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands and, possibly, even northern Hokkaido. The pincer movement would be carried out on the west by the 654,000-man Trans-Baikal Front, commanded by Marshal Rodion Malinovsky, while the 1st Far East Front, commanded by Marshal K.A. Meretskov and numbering 586,589 soldiers, attacked from the east. In the northeast, General M.A. Purkayev’s 2nd Far Eastern Front, comprising 337,096 men, would launch supporting attacks against the center of the pocket. This was to be a blitzkrieg offensive, relying on speed to preempt Japanese responses. Japan’s Kwangtung Army—estimated by Moscow to number over a million men but with an actual strength of 713,724 second-line troops organized into 24 infantry divisions, nine infantry brigades, and two tank brigades—was to be denied any respite to form new defensive lines.

The so-called Manchukuo Army, raised from local Chinese collaborators, numbered 170,000 men but possessed neither the will nor the means to give much combat support to the Japanese. Also aiding the Japanese were 44,000 cavalry troops in Inner Mongolia. Elsewhere in the theater—in Korea, Sakhalin, and the Kurils—the Japanese forces numbered 289,000 men. Most of the remaining divisions of the Kwangtung Army were newly formed from reservists, conscripts, and troops cannibalized from other units. Training was extremely limited in all units, and equipment and material shortages plagued the army at every level.

A Quantitative and Qualitative Armored Advantage

The most vital of the Soviet elements arrayed against the Japanese were the quantity and quality of its armored vehicles: a total of 3,704 tanks and 1,852 self-propelled guns. To offset the steep decline in combat efficiency of the Kwangtung Army, new plans called for delaying actions at the borders by a fraction of the army while the main Japanese forces gathered to hold a mere quarter of southeast Manchuria in the Tunghua area. The Japanese hoped the raw terrain, vast distances, and determined resistance would exhaust the Soviets before they reached the Tunghua area. Final plans, however, were not completed until June—too late to complete all the required redeployments and new fortifications. Even worse, lower echelon Japanese commanders remained ignorant of the plans, and millions of civilians in Manchuria were not warned that they would largely be abandoned to the Soviet invaders.

The Japanese defenders possessed 1,155 armored vehicles (mostly armored cars and light tanks), 5,360 artillery pieces, and 1,800 aircraft, of which only 50 were legitimate first-line planes. The Imperial Japanese Navy contributed nothing to the defense of Manchuria, the occupation of which it had always opposed on strategic grounds. Most of the Kwangtung Army’s heavy military equipment and best armored and elite infantry units had been transferred to the Pacific Theater over the previous three years. By 1945 the Kwangtung Army, with limited mobility and experience and almost no modern antitank weaponry, had only enough ammunition to issue its riflemen a meager 100 rounds apiece.

Failures in Japanese Military Intelligence

The Japanese military made several other grave miscalculations. Believing the western approaches from Mongolia were impassable due to the vast Mongolian desert and the natural barrier formed by the Grand Khingan Mountains, they assumed that any attack coming from the west would have to follow the old railroad line to either Hailar or Solun from the eastern tip of Mongolia. The Soviets did attack along these routes, but their main attack went through the supposedly impassable Grand Khingan range south of Solun into the center of Manchuria.

Japanese military intelligence also failed to determine how many soldiers the Soviets were actually transferring to the Siberian front. Marshal Vasilevsky’s original orders called for his forces to attack on the morning of August 11. When news of the American bombing of Hiroshima arrived, he was told to advance his timetable by two days. It was clear to the Russians that Japan’s surrender was imminent, and the need to physically occupy territory and ensure its subsequent jurisdiction became tantamount. Advance units of the Trans-Baikal Front crossed the border into Inner Mongolia and Manchuria at 12:10 am on the morning of August 9 without artillery or air preparation. The 6th Guards Tank Army, spearheading the front’s offensive, advanced in two columns of corps 45 miles apart.

The Kwangtung Army Capitulates

By nightfall, Russian reconnaissance units, forward detachments, and advanced guard units had reached the foothills of the Grand Khingan Mountains, 93 miles into Manchuria. Due to the rapid Soviet advance and ongoing Japanese redeployments, the only significant resistance came on the left flank, where the Soviet 36th Army’s assault route traversed fortified border installations. Meanwhile, Soviet and Mongolian mechanized cavalry and tank brigades on the right flank advanced in two huge columns and penetrated 55 miles into the arid wastes of Inner Mongolia, sweeping aside small detachments of Inner Mongolian cavalry. On the evening of August 9, in the absence of any notable Japanese reaction, the commander of the 6th Tank Guards Army made final plans for securing the mountain passes and beginning the difficult passage through them.

Progress of the 6th Guards Tank Army continued to be spectacular, although the task of resupplying its armored vehicles quickly became a problem. The advance corps began receiving airlifted shipments of fuel beginning on August 11. By August 14, the Trans-Baikal Front had crossed the Grand Khingan Mountains in all sectors and continued its advance, moving to secure the ultimate objectives of the campaign, the cities of Mukden and Changchun. On the northern flank, the 36th Army continued its siege of the Hailar fortifications in northwest Manchuria. Bypassed and isolated by the Soviet first echelon, the defenders at Hailar put up a fierce but losing battle. Although rated only 15 percent combat effective, the Japanese 80th Independent Mixed Brigade required the combined might of two Soviet divisions and an imposing arsenal of artillery to pound it into submission. On August 18, the surviving 3,827 defenders at Hailar surrendered.

On August 15, the Soviet-Mongolian Cavalry-Mechanized Group, advancing in two columns, ran into heavy opposition from the Inner Mongolian 3rd, 5th, and 7th Cavalry Divisions at Kanbao. After two days of fighting, General I.S. Pliyev’s southern column defeated the Inner Mongolians, took 1,634 prisoners, and occupied the city. On August 18, the Soviet-Mongolian units reached the outskirts of Kalgan. Although the Japanese High Command already had announced the capitulation of the Kwangtung Army, the defenders of the fortified region northwest of Kalgan didn’t end their resistance until August 21.

Japan’s Heavy Fortifications in Manchuria

With that accomplished, the Soviet-Mongolian Group crossed the Great Wall of China and proceeded toward Beijing, uniting on the march with units of the Chinese Communist 8th Route Army. Also on August 15, the 6th Guards Tank Army resumed its advance, opposed by decaying elements of the 63rd and 117th Japanese Infantry divisions and Mongolian cavalry forces. The Soviet 7th Guards Mechanized Corps moved east toward Chanchun, while the 9th Guards Mechanized Corps and the 5th Guards Tank Corps moved southeast toward Mukden. On the 19th, the main Soviet forces approached both cities, and two days later the united 6th Guards Tank Army occupied both Mukden and Chanchun, followed by the arrival of Soviet airborne detachments at both locations. Because of fuel shortages, further movement of the 6th Guards Tank Army to Port Arthur and Dalian was by rail.

The Trans-Baikal Front had now achieved its objectives well ahead of schedule; for all practical purposes, organized resistance ceased after August 18. Activity from that time on involved collecting prisoners, disarming Japanese units, and making administrative moves to occupy the remaining areas of central and southern Manchuria. Japanese units that had withdrawn into central Manchuria when the Soviet offensive began, such as the 117th Infantry Division or those units already deployed in central Manchuria, never significantly opposed the Soviets.

Marshal Meretskov’s 1st Far East Front faced conditions far different from those of the Trans-Baikal Front. The 435-mile frontage of the 1st Far East Front, running from the Ussuri River town of Iman to the Sea of Japan, was shorter, and the Japanese border districts of eastern Manchuria were more heavily fortified than those in the west. Some of the complexes were large, sophisticated, reinforced concrete structures. With no artillery bombardments except at Hutou, the Soviets advanced all along the front at 1 am on August 9 in the worst of weather conditions. Many attacks came over terrain the Japanese believed impassable to huge forces.

The Soviet 5th Army—12 divisions and 692 armored vehicles—spearheaded the front’s main assault. With three rifle corps abreast, it struck the front and north flank of the Volynsk center of resistance, held by one battalion of the Japanese 124th Infantry Division. Tanks and self-propelled guns supported each rifle division on the main axes of advance. By nightfall, the three corps of the 5th Army had torn a gaping hole 25 miles wide in the Japanese defenses and advanced 15 miles into the Japanese rear. Follow-on units reduced remaining Japanese strongpoints in the Volynsk, Suifenho, and Lumintai sectors. The 1st Far East Front’s primary objective was the heavily fortified road junction of Mutanchiang, a crucial communications center and headquarters of the Japanese First Area Army. Impressed with the progress made by his 5th Army, Meretskov ordered the acceleration of the advance upon that city. On the night of August 11, advance units of the 5th Army approached the outer fortifications of Mutanchiang, setting the stage for one of the few multidivision, set-piece battles in the Manchurian campaign. The 1st Red Banner Army supported the attack of the 5th Army by advancing on the right (northern) flank. Opposing the Soviets and waiting behind heavily forested terrain were the Japanese 126th Infantry Division and elements of the 135th Infantry Division.

Soviet divisions were forced to build roads through the forest to advance; many Japanese, never learning that they had been ordered to withdraw, resolved to fight to the death. The battle raged for two full days beginning on August 15 and accounted for half the Soviet casualties in the entire campaign. After Soviet tanks penetrated all the way to the headquarters of the 126th Division, a squad of firemen from a transport unit, each armed with a 15-kilogram explosive, attacked the five lead tanks in a suicide charge, one tank per man, and successfully demolished all five tanks.

Reaching the 38th Parallel

After the 1st Red Banner Army finally cleared the city on the night of August 16, it began an advance to the northwest in the direction of Harbin; meanwhile, units of the 5th Army skirted south of the city to continue southwest toward Kirin and Ningan. On August 18, with the final announcement of Japanese capitulation, the 1st Red Banner Army and the 5th Army deployed to receive and process surrendering Japanese units.

On August 20, elements of the 1st Red Banner Army reached Harbin, where they united with Soviet airborne forces and with amphibious forces of the 15th Army, 2nd Far East Front. In the southern sector of the 1st Far East Front’s area of operations, meanwhile, combined-arms Soviet armies attacked to the west and southwest; one objective was to cut Japanese communications from Korea to Manchuria. With Japan’s surrender pending, rifle units of the Soviet 25th Army, with naval support, staked out claims along the northeastern face of the Korean Peninsula through a series of overland marches and amphibious landings. By the end of August, Red Army units had reached the 38th Parallel, the previously agreed-upon demarcation line for the shared occupation of Korea.

Supporting operations of the 2nd Far East Front took place on a broad front over a wide variety of terrain. Some of the bitterest fighting in the campaign occurred when Japanese units of the 134th and 123rd Infantry Divisions and the 135th Independent Mixed Brigade resisted the Soviet advances. General Purkayev deployed his forces in three separate sectors, each with distinct axes of advance and objectives. The main attack came in the center, where Lt. Gen. S.K. Mamonov’s 15th Army—three rifle divisions—crossed the Amur River and overwhelmed the enemy’s fortified regions at Fuchin. It then advanced along the Sungari River via a gap in the mountains to Harbin in central Manchuria, where it united with units of the 1st Far East Front. The 2nd Far East Front completed its mission successfully—tying up Japanese forces in northern Manchuria and preventing them from intervening in the main attacks further south—although not without difficulties.

The Battles for the Kurils

The Russians contended with constant bad weather and difficult terrain as well as resistance as formidable as anywhere else in the theater; the difficulties it encountered were due in part to warnings the Japanese had of the attack, and the difficulties the 2nd Red Banner Army experienced moving its forces across the Amur River as it took up positions on the right flank of Mamonov’s 15th Army. While Soviet armies completed the occupation of Manchuria after the Japanese surrender, amphibious units were assaulting the Pacific islands promised to Stalin at Yalta. Some 8,000 soldiers were dispatched across 500 nautical miles of sea to the Kurils. The northern Kurils were defended by 25,000 Imperial troops, of which 8,480 were deployed on the northernmost island of Shannshir, 18 miles in length and six feet wide.

On the night of August 14, Shannshir’s senior officer, Maj. Gen. Fusaka Tsutsumi, was instructed to listen to the emperor’s broadcast the next day. Having done so, Tsutsumi awaited the arrival of an American occupation force, which he had no intention of fighting. Instead, in the early morning hours of August 18, without warning or parley, a Russian division assaulted Shannshir. The Red Army knew little about the difficulties of opposed landings from the sea, and it possessed none of the Allies’ inventory of specialized amphibious equipment. As could have been predicted, the Shannshir operation turned chaotic for the landing force, garrison troops without combat experience.

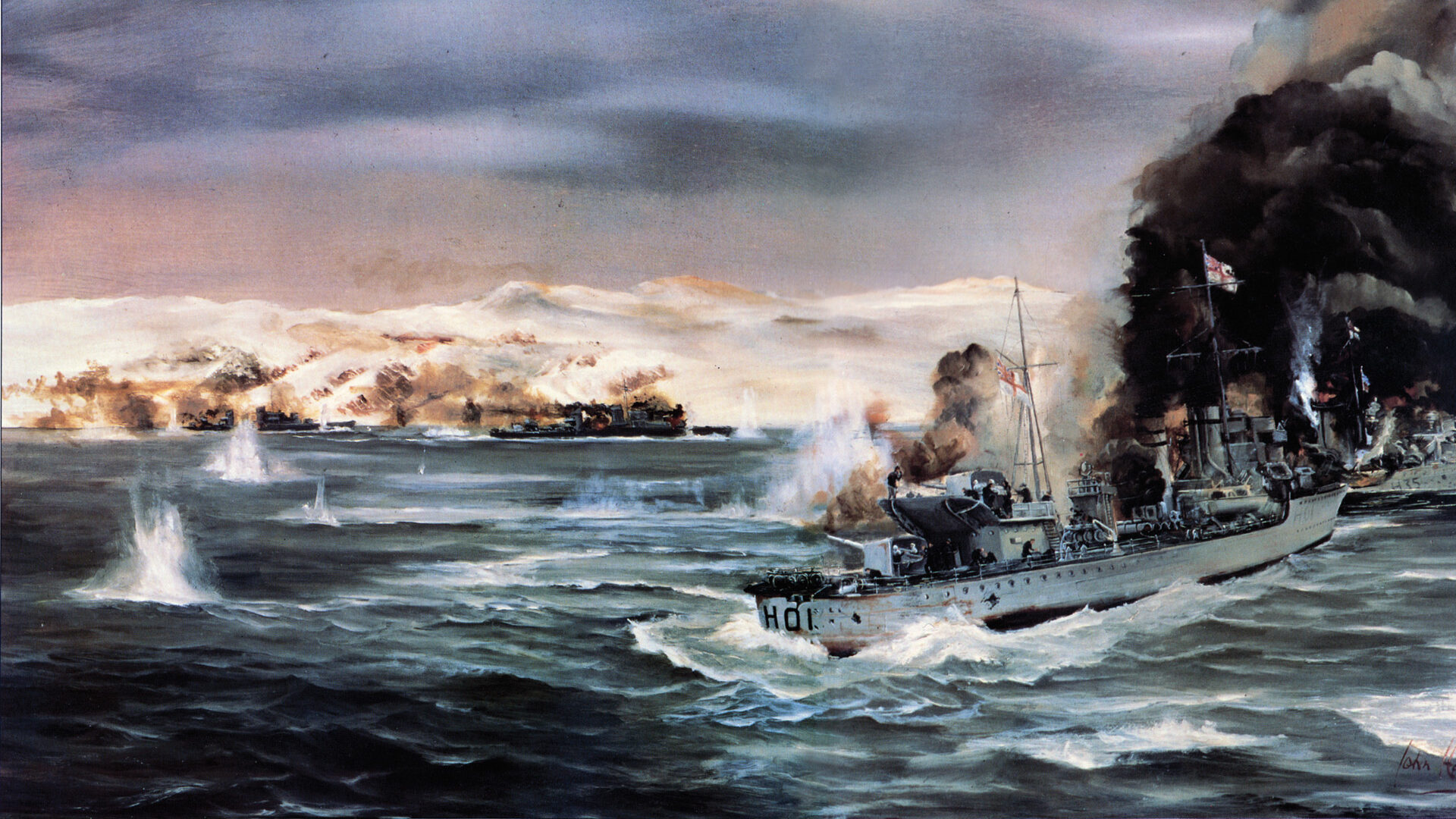

At 5:30 am on August 18, Japanese shore batteries opened fire on Soviet ships as they made their approach, sinking some and setting others afire. The invaders’ communications collapsed as Russian sailors labored under heavy fire to improvise rafts to land guns and tanks. A counterattack by 20 Japanese tanks gained some ground, and what was almost certainly the last kamikaze air attack of the war struck a Soviet destroyer escort. On the morning of August 19, the Soviet commander on Shannshir received orders to hasten the island’s capture. Soon afterward, a Japanese delegation arrived at Russian headquarters to arrange a surrender. The next morning, however, some coastal batteries still fired on Soviet ships in the Second Kuril Strait and were heavily bombed in return. Tsutsumi’s men finally quit fighting on the night of August 21, having lost 614 men killed.

The Bitter Battle for Sakhalin

Sakhalin represented a less serious challenge, for its nearest point lay only six miles off the Asian coast and its northern part was Soviet territory. The island was vastly larger, however, 560 miles long and between 19 and 62 miles wide. Japan had held the southern half since 1905, a source of bitter Russian resentment. Sakhalin’s terrain was inhospitable: swamp ridden, mountainous, and densely forested. For reasons of pride, the Japanese had lavished precious resources on fortifying the place, and, as a result, the Soviet troops who began the assault on August 11 made scant headway. Only after bitter fighting did the Soviets capture the key strongpoint of Honda, where defenders fought to the last man.

The weather was poor for air support, and many Soviet tanks became bogged, leaving the infantry to struggle through on foot in an attempt to outflank the Japanese positions. Early on August 16, the Japanese launched human-wave counterattacks, allowing the Russians to inflict massive casualties. The next day, yard by yard, Soviet troops forced passage through the forests, battering the defenders with air attacks and artillery. On the night of August 17, the local Japanese defenders in the frontier defensive zone surrendered. Elsewhere on Sakhalin, scattered garrisons continued their resistance. When the Soviet Northern Pacific Flotilla landed a storming force at the port of Maoka on August 20, they mowed down civilians at the shoreline, after which Japanese troops opened fire. Thick fog hampered gunfire observation, and defenders had to be painstakingly cleared from the quays and then the city’s center. A Soviet account later claimed disingenuously that “Japanese propaganda had successfully imbued the city’s inhabitants with fears of ‘Russian brutality.’” The result was that much of the population fled into the forests, and some people were evacuated to Hokkaido. Women were especially influenced by the propaganda, which convinced them that arriving Russian troops would shoot them and strangle their children.

The Soviets claimed to have killed 300 Japanese in Maoka and taken another 600 prisoners; the rest of the garrison fled inland. Sakhalin was finally secured on August 26, four days behind the Soviet schedule. Stalin harbored more far-reaching designs on Japanese territory. Before the Manchurian assault began, Soviet troops were earmarked to land on the Japanese home island of Hokkaido, and to occupy its northern half as soon as northern Korea was secured. On the evening of August 18, Vasilevsky signaled Moscow, asking permission to proceed with a Hokkaido attack scheduled to last from August 19 to September 1. For 48 hours, Moscow was silent, brooding. After a second request for orders was sent by Vasilevsky on August 20, he was told by Stalin to continue preparations and be ready to attack on the night of August 23. Meanwhile, the Americans considered possible landings in the Kurils and at the mainland port of Dalian to secure bases—in breach of the Yalta agreement—before the Soviets could reach them. Both sides, however, finally backed off. Washington recognized that any attempt to preempt the Soviets from occupying their agreed territories could precipitate an unwanted crisis.

The Soviet Invasion of Manchuria: The Political Justification, According to the Russians

After Truman cabled Moscow, summarily rejecting Stalin’s proposal that the Russians should receive the surrender of Japanese forces on north Hokkaido, Moscow on August 22 dispatched new orders to its Far East Command, canceling the proposed Hokkaido landings. The Americans confined themselves to hastening Marine forces to key points on and near the coast of mainland China with orders to hold these until Chiang Kai-shek’s forces could assume control. Only a huge American commitment of men and transport aircraft enabled the Nationalists to reestablish themselves in the east during the autumn of 1945. In Manchuria and the island operations, the Soviets claimed to have killed, wounded, or captured 674,000 Japanese troops, at a cost to the Red Army of 12,031 dead and 24,424 sick or wounded. Stalin’s Far Eastern conquests thus incurred about the same human cost as the American seizure of Okinawa. Japan claimed 21,000 killed, but the true figure was probably closer to 80,000. Far from the Soviets fulfilling others’ fears that they would prolong their presence in Manchuria for imperialistic reasons (Stalin had promised the Allies to recognize Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists as the sole legitimate government in China), Chiang had to beg Stalin’s occupying forces to remain long enough to allow the Nationalists time to send their own troops to take possession.

The Soviets withdrew between January and May 1946, having systematically pillaged the region of every scrap of industry. They justified this by claiming that their booty was not Chinese property but Japanese owned and thus represented legitimate war reparations. The victors took home everything they could move; they dismantled steel mills and other industrial plants and used the confiscated Manchurian railway to ship the spoils back to the Soviet Union. Hundreds of thousands of Japanese captives, civilian and military alike, found themselves laboring for the Russians in Siberia for long periods of time, enduring extremely harsh conditions on substandard rations.

“They Had No Respect for Our People”

Chiang Kai-shek’s occupation of Manchuria proved strategically unwise; his forces there found themselves cut off when the Chinese civil war erupted. Vast quantities of American military aid provided to his armies counted for nothing beside the corruption and incompetence of his regime. In 1949, Mao Zedong became master of China, excluding only the island of Formosa, which became Chiang’s pocket nation-state, modern-day Taiwan.

The Japanese slogan “Asia for Asians” achieved fulfillment in a fashion undreamed of by those who had coined it. Both within and without Manchuria, the Chinese had received news of Stalin’s onslaught with mixed feelings; in the first days, local people greeted the Soviet armies enthusiastically. The days and weeks that followed the Russian occupation, however, came as a brutal shock to the allegedly liberated citizens of many towns and villages. Manchurian women, rejoicing at the defeat of the Japanese, soon became horrified at the conduct of the Russians, as they found themselves facing wholesale rape—a favorite tactic by Russian soldiers across occupied Germany and Eastern Europe.

Communist guerrilla Zuo Yong was among those appalled by the behavior of many members of the Red Army: “The Russians were our allies—we were all in the same boat,” he said. “We thought of their soldiers as our brothers. The problem, however, as we discovered, was that they had no respect for our people.” Another guerrilla, Jiang De, added with a shrug, “The Russians simply behaved in the same way they did everywhere else.”

Some maps would have helped illustrate this story.