By Louis Ciotola

The final outcome of the Franco-Prussian War was decided on September 2, 1870. On that day, more than 100,000 French troops, including Emperor Napoleon III, surrendered to the Prussian Army at Sedan. But despite the crushing German victory and the crippling loss of their head of state, the French were not prepared to admit defeat. The heart of their nation, the city of Paris, had yet to fall, and honor dictated that until it did France must fight on. The Prussian leadership understood this as well, knowing that to finish the war victoriously they would have to take the French capital, a city they considered a den of iniquity and mockingly branded the new Babylon. Neither side had any misconceptions regarding the long and grueling struggle that lay ahead. It would be a bitter test of national pride and human perseverance.

The moment affairs were settled at Sedan, the Prussian military leadership, helmed by Chief of the General Staff Helmuth von Moltke and Minister of War Albrecht von Roon, sent their armies racing toward Paris. With one French army freshly wiped out, another under siege at Metz, and no new ones prepared to do battle, the road to the capital was wide open. Moltke and Roon ordered most of their forces to Paris, leaving only elements of the First and Second Armies under Prince Frederick-Charles of Prussia to continue the investment of Metz and Strasbourg. Nothing could prevent a siege of Paris. For France, it was only a matter of how long the war could be dragged out, in the slender hope that such resistance would wear down the German alliance or attract outside intervention.

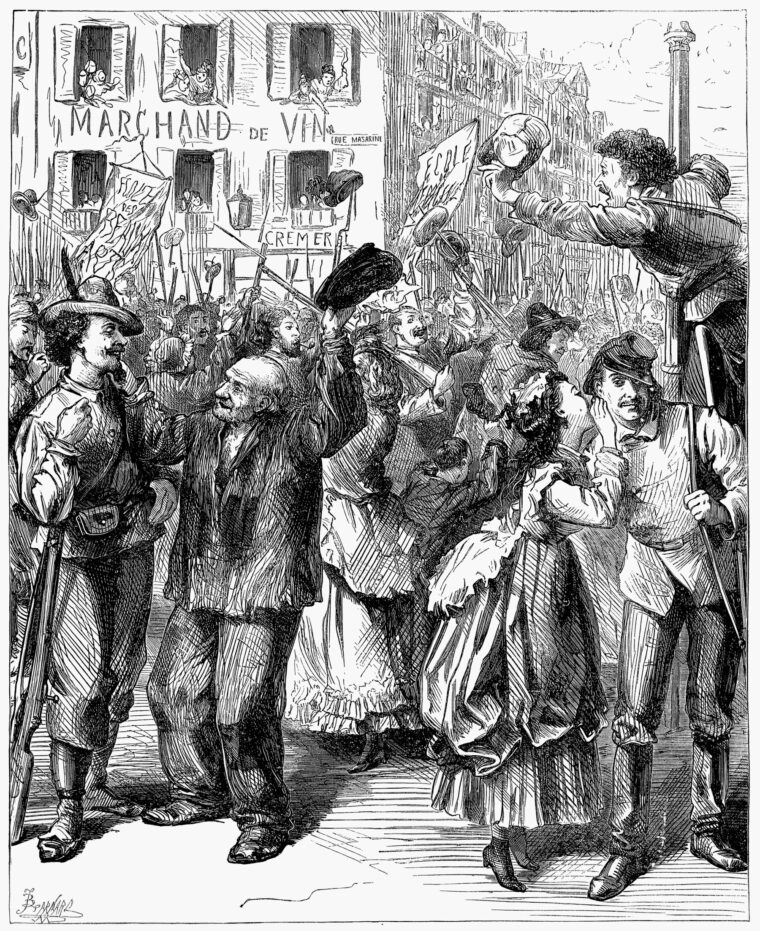

Parisians learned of the disaster at Sedan on September 3, and cries went up immediately to overthrow Napoleon. Most prominent among the voices was that of Jules Favre, a Parisian deputy who had fiercely opposed the war. Favre made a parliamentary motion calling for Napoleon’s abdication, and the following day a mob of 60,000 Parisians chanting “Death to the Bonapartes!” and “Long live the nation!” massed in support of a republic. Favre and his chief compatriot, Assemblyman Leon Gambetta, along with other notable Parisian leaders, were swept up by the mob and taken to the Hôtel de Ville, where French republics traditionally were proclaimed.

Favre and Gambetta were unprepared to proclaim anything more than a provisional government, and on September 4 they formed the Government of National Defense, the first governing body of the Third French Republic. General Louis Trochu was named president, Favre became vice president and minister of foreign affairs, and Gambetta was appointed minister of the interior. The new government was dominated by moderates, but leftists were also present in the political lineup. The leftists, or “Reds,” pushed for a communal style of government and demanded that the war against Prussia continue to the bitter end. Others, like Favre, hoped that France’s change of regime would prompt Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck to call for an armistice.

Paris Prepares for the Prussian Advance

With an immediate armistice unlikely, Paris prepared to endure a lengthy siege. Between 1840 and 1870, the French government had spent more than 140 million francs upgrading the capital’s defenses. The result was a truly modern fortress of epic proportions that would be virtually impossible for the Germans to take by storm. A 30-foot wall surrounded the city, behind which lay a moat crowded with a flotilla of gunboats and a series of 16 external forts. The total perimeter of the fortifications was 38 miles, meaning that an enemy army would have to create a front at least 50 miles long to effectively invest Paris. Such a prospect meant that the besieging army would be spread dangerously thin. Paris’s 3,000 cannons made the task before the Germans even more daunting. With 450 shells per artillery piece, the French were equipped to give as good as they got.

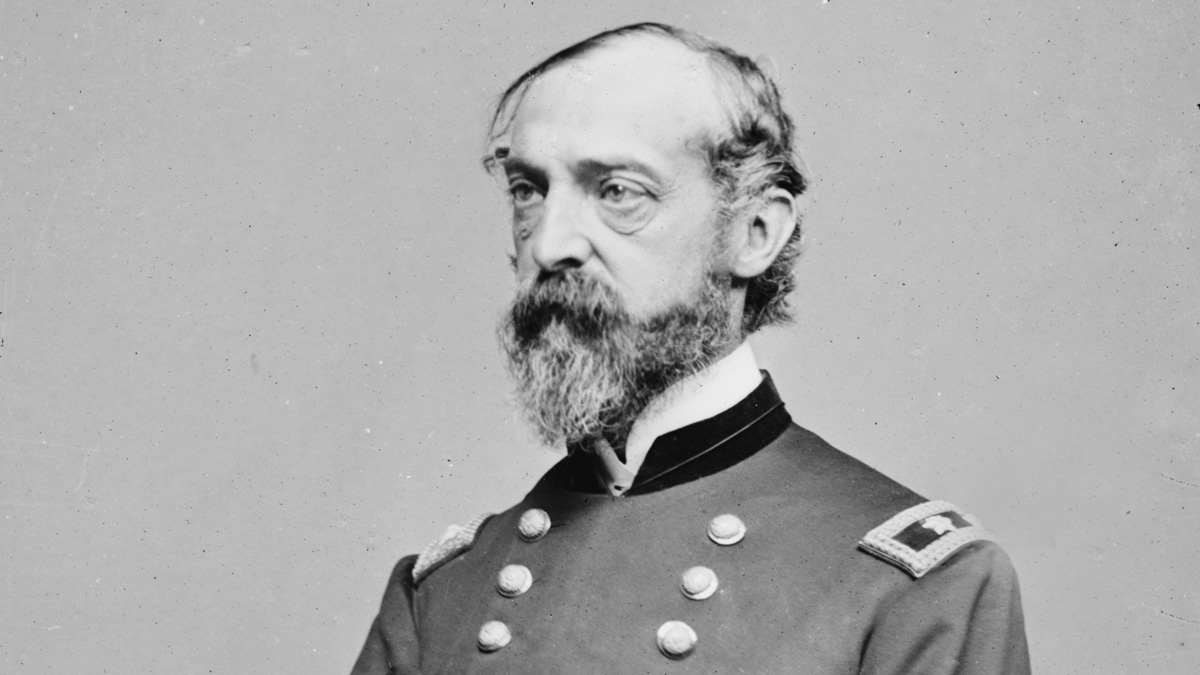

Trochu wasted no time putting his men to work bolstering the existing defenses; as far as manpower was concerned, there was no shortage. XIII Corps under General Joseph Vinoy, having failed to reach Sedan in time, fell back to defend Paris following the battle. Combined with additional stragglers, 60,000 regular army personnel now manned the city’s defenses. They were supplemented by 13,000 naval veterans and more than 100,000 volunteer soldiers, known as Mobiles, from the provinces. Behind them was the 350,000-man National Guard, or Garde Sedentaire. Although massive in number, the Mobiles and the Garde, which was essentially the people of Paris in arms, were poorly trained and lacked experience. Trochu conceded, “We have many men, but few soldiers.”

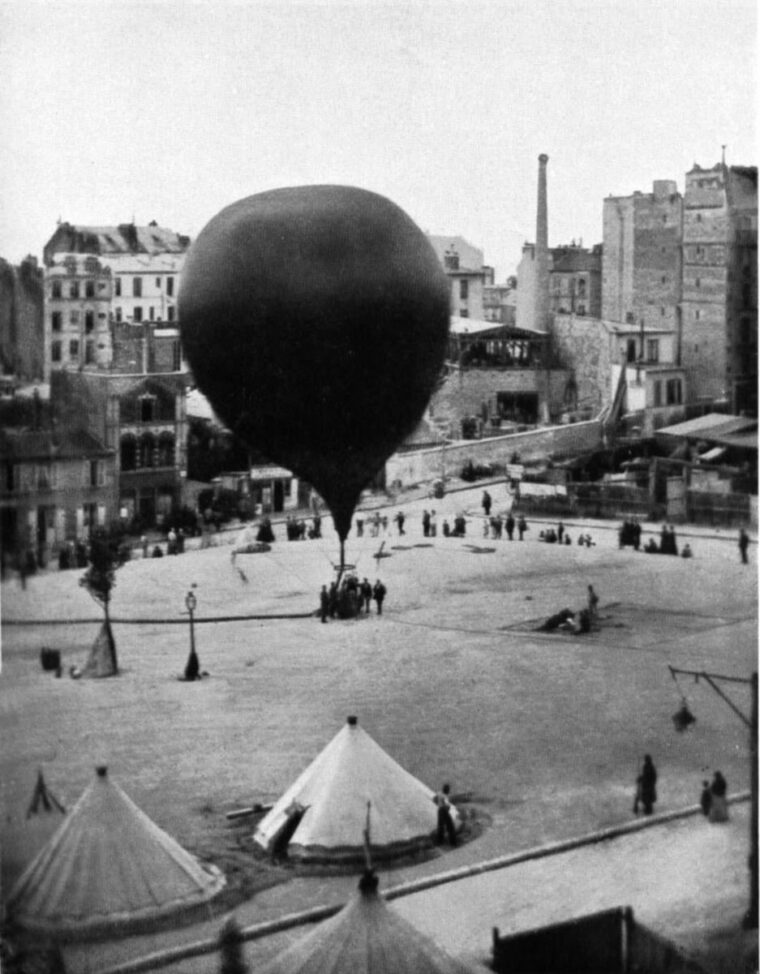

Nevertheless, Paris made a monumental effort to prepare for the siege. The entire city was virtually transformed overnight into a gigantic arsenal. Factories were converted to manufacture war matériel, the Louvre museum became an armament shop, Orleans Station produced balloons for communicating with the provinces, and Gaité Theatre made uniforms. Hospitals sprang up to take care of the anticipated sick and wounded, and bivouacs were set up to house the soldiers. The greatest fear among defenders was the prospect of disease and famine that a long siege inevitably would bring. Eighty days’ worth of flour, grain, and fuel were procured for the estimated two million people of Paris, not including the hundreds of thousands of troops. Soldiers herded livestock from the surrounding countryside into the city and began digging graves to stave off epidemics.

“A Heroic Folly”

Despite the grim prospect of starvation and disease, the people of Paris remained almost naively upbeat, trusting fully in their defenses. Their spirit was infectious and convinced numerous foreign observers that Paris would fight to the death. The crown prince of Prussia, Frederick-William, was not convinced. He wrote in his diary on September 16 that the people of Paris did not share the enthusiasm of their newspapers. Only two days earlier, Trochu had led a massive military parade through the city and publicly declared, “Never has any general had before his eyes such a spectacle as you have just given me.” Privately, however, he was more realistic, calling the siege “a heroic folly which we will commit to save the national honor when all else is lost.”

The Germans gave the Parisians little time to increase their confidence. On September 17, they began encircling maneuvers. The Army of the Meuse under Albert, crown prince of Saxony, moved to the north of Paris, while Frederick-William veered the Third Army to the south. In all, some 122,000 German infantry and 24,000 cavalry snaked their way around the city. Moltke’s men found the surrounding countryside stripped bare, with all roads, bridges, canals, and railroads destroyed. The result was an even greater dependency on growing supply lines, which Moltke was forced to defend with more and more men. Never far from his mind was the fear that the French could mass their forces to exploit Prussian weaknesses and possibly even break out from the besieged city.

The French were not about to allow the encirclement of Paris without a fight. One of the fieriest generals, Auguste-Alexandre Ducrot, demanded immediate action, and on September 19, with Trochu’s consent, he struck the Prussians along the Versailles road. His goal was to secure the Châtillon Heights, but Ducrot was able to capture only one redoubt. The French ranks, packed tightly together, were sitting ducks for the Prussian artillery. Ducrot withdrew when he realized the endeavor had become pointless.

The Prussians chose not to pursue their foe into the southern fortifications, a decision that indicated clearly their planned strategy of siege over attack. The following day, the siege began officially when cavalry patrols from Albert’s and Frederick-William’s armies met at St. Germain-en-Laye, cutting off the last road from Paris. The Germans then began to settle in, comfortably inhabiting the surrounding villages, most of which had been abandoned by their former residents. In striking contrast, the French survivors of Châtillon returned to Paris and received harsh ridicule that almost descended into a riot.

By the end of September, the number of German troops surrounding Paris had grown to over 200,000. General Leonhard von Blumenthal, chief of staff to Frederick-William, voiced lingering concerns. “Our lines are so weakly held that, if the enemy should attack at one point with the whole of his force concentrated, we must be beaten back and have our line cut through,” he said. “Fortunately, he does not understand his business, and wastes his strength striking out blindly in all directions.”

Gambetta’s Flight from Paris

By early October, the French defenders realized that the Germans had no intention of storming the city. The siege bogged down into little more than minor artillery duels. As a result, both soldiers and civilians grew increasingly bored—a potentially dangerous development for the new republic. Political agitation on the left was beginning to stir. Balloons leaving Paris regularly took news to the provinces, but information reached the capital much more sporadically. The city was rife with rumors that the Prussians were retreating, a patent falsehood that only served to increase civil unrest.

Boredom was beginning to demoralize the German soldiers as well, but Bismarck remained obstinate regarding the war. Meeting with Favre, the Prussian chancellor pushed demands for Alsace and the German-speaking portion of Lorraine. Negotiations went nowhere. Meanwhile, morale in Paris received a slight boost with Gambetta’s successful balloon flight out of the city. A large crowd gathered to watch as the minister soared out of sight, determined to keep the war effort going in the provinces.

The Fight for Le Bourget

The French spent October testing the German perimeter and fine-tuning their tactics in preparation for a future breakout. Minor sorties against L’Hay and Châtillon failed to gain ground, but they did yield valuable experience for the untested soldiers on how to advance with covering fire. On October 21, Trochu ordered his men to attack the Sannois Plateau, the anticipated target for a future massive sortie. A total of 8,000 troops participated in the attack, suffering 500 casualties and capturing nothing. Trochu, however, viewed the sorties as a success, convincing him that a breakout was within the realm of possibility. Unfortunately for civilian morale, Parisians mistook the minor assaults for fully committed attacks and grew increasingly resentful with each withdrawal.

On the night of October 27, a more serious attack took place on Le Bourget, a fortified town in German hands just north of the investment line. Ambitious French commander Carey de Bellemare, ignoring the fact that the town was surrounded by heights occupied by German artillery, commenced a daring night assault with 250 of the most aggressive soldiers in Paris. As he had anticipated, French victory was swift.

Proud of his accomplishment, de Bellemare met with Trochu to ask for both reinforcements and a promotion, spurred on by Parisian newspapers praising the rare victory. Trochu did not share in the excitement, but rather was outraged by de Bellemare’s impetuousness. Le Bourget, Trochu said, was indefensible, and its capture merely increased the death toll for no good reason. Even the typically aggressive Ducrot backed his commander’s position on the matter. De Bellemare continued to press his case, but Trochu refused to reinforce the town.

Meanwhile, the Germans were also hotly debating the value of Le Bourget. Many among them, most prominently Moltke, thought the position as precarious as Trochu did. Frederick-William, for one, considered the fort not worth retaking. The commander in the sector, Crown Prince Albert, however, took its recapture as a matter of pride. On October 29, he ordered a strong reconnaissance of the new enemy position with every intention of attacking in force as soon as possible.

As soon as the reconnaissance force returned, Prussian artillery opened fire on Le Bourget from the surrounding heights. At 8 am on the 30th, 6,000 soldiers of the Prussian Guard swarmed forward, utilizing the new tactic of spread-out skirmish lines to reduce the impact of the French guns. Before long, the Prussians were inside the town, battling tenacious defenders house to house. The Prussian surge became irresistible; the French withdrew after the loss of another 1,200 men. Although the Prussian loss was a mere 477, the victory did nothing to alter the opinion of many in the Prussian leadership that the entire incident had been completely pointless.

The Coup in Paris

As the fighting raged in Le Bourget, Parisians were getting word of a worse catastrophe. News arrived that 173,000 French soldiers had surrendered at Metz. As at Sedan, an entire army had been lost. Frederick-Charles was free to either aid in the siege of Paris or advance on Tours in order to halt Gambetta’s efforts to forge a new provincial army. Then came the last straw. In what was impeccably bad timing, eminent statesman Adolphe Thiers returned to Paris bearing the news that his attempts to procure outside help for France had proven fruitless. Thiers urged the government to accept Prussian terms for an armistice. The radical left accused the government of treason. Having believed government propaganda that victory was still possible, Parisians were shocked by Theirs’s revelations. With spirits at a new low, the situation was ripe for an uprising.

Within hours, tensions came to a boil. What began as left-wing demonstrations quickly turned into a coup. The Reds invaded the Hôtel de Ville, taking the government hostage and declaring a commune. Hours later, however, the insurgents lost their nerve when a battalion of Mobiles entered the basement of the building. The communards fled, some escaping while others were arrested. Their indecisiveness cost them their revolution, and the incident convinced Bismarck that peace talks with the unstable French were pointless.

“I shall only re-enter Paris dead or victorious”

The new French republic was saved, but morale remained low as conditions within the city continued to deteriorate. Fuel reserves were slowly disappearing, and winter was just around the corner. Food supplies were becoming scarce, and the weakened population became increasingly susceptible to smallpox. Then, as if part of some wonderful dream, magnificent news arrived in Paris. On November 9, Gambetta’s new Army of the Loire won a great victory over the Prussians at Coulmiers and triumphantly reentered Orleans. For the first time in the war, France had a victory of substance to celebrate. Trochu and Ducrot had renewed reason to attempt a massive breakout.

Throughout October, Ducrot planned a giant attack in the northwest toward the Sannois Plateau. The point of assault was Gennevilliers, where a small peninsula was formed by the Seine and German defenses were weakest. Upon breaking out, the French army would head for the channel coast where, with the assistance of the navy, it could organize resistance with the provinces. The pessimistic Trochu had little faith in the plan but felt compelled to allow it to go forward. He demanded, however, that Ducrot change the point of attack to the Châtillon Heights and attempt a linkup with Gambetta advancing out of Orleans.

The change in plans required moving tens of thousands of men and nearly 400 guns laboriously across Paris to the new target area. Trochu compromised with a plan to attack southeast across the Marne and a swing west to merge with the Army of the Loire. The revised strategy offered the chance to cut off the Prussian headquarters at Versailles from the principal German railhead at Lagny and sever supplies south of Paris.

The changes left little time to revise the plan, and things went sour from the start. The balloon carrying word of the new plan to Gambetta failed to reach its intended target, sailing off course for 15 hours and eventually landing in Norway. Meanwhile, Prussian intelligence had advance word of the planned sortie, and Moltke ordered the southern front reinforced. On the morning of November 29, the French government issued a proclamation announcing the sortie to the people of Paris. Ducrot boldly declared: “I swear before you and the entire nation; I shall only re-enter Paris dead or victorious.” Inspired by such words, Paris overflowed with confidence. Unfortunately, other French commanders did not share those sentiments.

From Defeat to Disaster

Things began badly. Heavy rain from the previous few days had left the Marne dangerously swollen. Debris from blown bridges clogged the river, and it was not until daybreak that pontoons were in place. Ducrot began to panic, but fear of a riot in Paris precluded any notion of canceling the attack. Trochu agreed to postpone the primary assault until the following day, but he neglected to call off the diversionary assaults. As a result, attacks by Vinoy on Choisy-le-Roi and L’Hay went unsupported and cost 1,300 needless casualties. A second assault at Malmaison was equally disastrous. Meanwhile, Moltke calmly reinforced the threatened sector with a division of Saxons as Parisians celebrated prematurely in the streets.

Early on November 30, the French established bridgeheads over the Marne at Champigny and Brie and, with the aid of artillery, easily secured the towns. The next objective was to prove more difficult. Ascending the Villiers Plateau, the French were met by heavy fire from the defending Württemburgers. Well dug in and shielded by a stone wall, the Württemburgers were relatively safe from artillery and rifle fire while being free to unload upon the enemy. Nevertheless, the French charged fearlessly, surging forward three times but failing to dislodge the enemy. Their dead littered the field.

Ducrot was the most fearless among them. He rode his white horse into the face of enemy fire as if intending to die as his proclamation the day before had promised. Seeing the offensive stalled, he ordered III Corps to launch a flanking attack against the Villiers Plateau by way of Neuilly and Noisy-le-Grand. Due to a shortage of pontoons, the corps did not move until afternoon. Meanwhile, Ducrot initially mistook newly arriving Saxon troops for III Corps. Fortunately for him, he was able to amend the error with quick thinking. Ordering his men to lay prostrate, Ducrot surprised the Saxons at close range and sent them scrambling away.

Ducrot’s improvisation successfully gave III Corps more time, but it soon proved to be in vain. When the first division arrived under de Bellemare—of all people—it marched in the wrong direction, uselessly advancing on Brie rather than Noisy-le-Grand. At the same time, the Germans wrecked another flanking attack at Coeuilly. Ducrot made up his mind that the sortie had failed, but retreat was impossible—Paris would explode. His only option was to go on the defensive. By nightfall, only Champigny, Brie and a tiny fraction of the Villiers Plateau remained in French hands. Almost nothing had been gained, at the cost of an additional 5,200 men. The Germans lost half as many.

Defeat turned into disaster when Gambetta, misinformed by Favre via balloon message that the sortie was a success, divided his army and marched on Fontainbleau. Frederick-Charles was ready—the result was a foregone conclusion. The crushing of the Army of the Loire came while survivors of the great sortie trudged despondently back into Paris and desperate French soldiers combed the battlefield in search of meat from dead horses.

To Bombard Paris

Ducrot requested a 24-hour truce in order to collect his wounded, a proposal the Prussians eagerly accepted since it gave them time to prepare a counteroffensive. On the morning of December 2 the Prussian guns opened fire. The bombardment was fierce, but the French stubbornly bore its deadly brunt. When the Germans charged forward, the defenders refused to budge. The attack nearly broke through at Champigny, but the French fought tenaciously and eventually forced the enemy to pull back. By the end of the day there was barely any change in the front.

The French resistance had been so potent that Moltke feared a counterassault. Ducrot thought otherwise. Although depressed by the prospect of reentering Paris in defeat, he could not sanction renewing the sortie. In all, 12,000 French soldiers had been lost, along with all hope of victory. The next morning he ordered his men back across the Marne and offered his resignation, determined to die as a common soldier in the ranks. Trochu refused.

Parisians scarcely reacted to news that the sortie had failed. More pressing concerns preoccupied their minds. Hunger was now the biggest issue. Political agitation took a backseat as the population used all its energy to simply stay alive. The price of food had skyrocketed, and what food remained was far from the typical Parisian diet. Horse meat was consumed regularly by citizens and soldiers, along with cats and dogs. Not surprisingly, the one-time pets developed an acute fear of humans, as did the hardy rats, which also became a hot commodity. Citizens even raided the zoos, making meals of everything from elephants to kangaroos. Only the lions, tigers, and monkeys were spared.

Although better supplied and less miserable than their French counterparts, the German soldiers were also growing tired of the stalemate around Paris. The German public was tired as well. Bismarck, keenly attuned to such sentiments, feared that the war was taking too long and favored bombarding Paris into submission. Prior to the siege he had brazenly remarked that “eight days without café au lait” would break Parisian spirits. Now he feared that the continuing resistance would tempt foreign powers to intervene against Prussia, especially Great Britain, where public sentiment was sympathetic to the Parisians’ plight.

Moltke, however, opposed the strategy as counterproductive, arguing that the earlier bombardment of Strasbourg had increased French resolve rather than shattering it. Bombing Paris, he warned, would be a waste of ammunition and a logistical nightmare. Becoming increasingly impatient with the generals, Bismarck threatened his king, William, with political turmoil in Berlin should the bombardment not occur.

Bombarding Paris into Submission

The French refused to sit idly by while the Prussians pondered whether or not to bombard the capital. Yet another sortie was launched against Le Bourget. What transpired on December 21 was the most pathetic French debacle to date. The Prussians greeted their assailants with heavy artillery fire. French marines charged forward through the freezing cold into a deathtrap. Sheer perseverance alone enabled them to reach Le Bourget, but exhaustion prevented them from maintaining the house-to-house combat that followed. The French troops failed to even reach Le Bourget, their dense ranks annihilated by Prussian artillery.

Meanwhile, a subsequent offensive under Vinoy met equally disastrous results at Villie-Evrard. Having successfully taken the town, Vinoy’s men were surprised hours later when the German defenders, who had taken refuge in cellars, suddenly emerged from their hiding places. Shocked, the French evacuated the village in complete disorder. In all, the two sorties cost the French another 2,000 casualties.

At a council of war on December 17, Prussian leaders concluded at last that Paris must be bombarded into submission. “The men are freezing and falling sick,” cried Bismarck, “the war is dragging out, the neutrals are interfering in our affairs, and France is arming.” Moltke relented. Only Frederick-William voiced objections, citing humanitarian reasons against shelling civilians. The king sided with Bismarck, ordering the bombardment of Paris to commence as soon as possible.

On January 5, 1871, the heavy guns opened fire on Paris. In the space of four or five hours each day, usually beginning around 10 pm, Prussian artillery heaved between 300 and 400 shells into the French capital. There was little accuracy. Anything could be hit. Overall, the bombardment did very little damage. The casualty rate, which totaled only 97 dead and 278 wounded, was low enough that Parisians could go about their daily lives as usual. Morale remained unchanged; in fact, some Parisians took heart in the belief that the bombardment was a sign of Prussian desperation. Ironically, more Germans were dying as a result of the bombardment than French; their gun crews were painfully close to the front line and exposed to snipers.

Cold and hunger remained the true killers in Paris along with a new threat, typhoid fever, caused by the necessity of drinking unfiltered water from the filthy Seine. Particularly horrible were the frequent scenes of malnourished children wandering the streets in search of food and eating the bark from trees lining the Champs-Elysees.

Trochu’s Last Sortie

Hope ran out. On January 15, the French government began to seriously debate capitulation. The Mobiles protested that the National Guard had not yet shed blood for the nation; the Guardsmen were eager to prove them wrong. With his men pining for another sortie, Trochu could hardly refuse without risking open rebellion. On January 16, he decided to make one last strike toward Versailles, the strongest sector in the German line. Trochu ordered Vinoy on the left to attack Montretout, while de Bellemare in the center moved against Buzenval, and Ducrot on the right stormed Malmaison. Such a complicated plan invited catastrophe.

The sortie was set to commence at dawn on the 19th, but Ducrot’s column, impeded by mud and fog, did not arrive at its staging area at the appointed time, compelling Trochu to delay the attack. Finally, fearful of losing what little tactical surprise he had, he ordered the sortie to begin at 10 am without the right column. Almost miraculously, things started well for the French. Vinoy reached St. Cloud while de Bellemare’s troops ascended the Garches-La-Bergeria Plateau.

By noon, Prussian worries subsided as both Vinoy and de Bellemare ran out of steam and ground to a halt. When Ducrot finally arrived that afternoon, he could not get his troops to advance, despite his usual heroics on his white horse. The National Guard, which the day before had boasted about its military prowess, fought horrendously, inflicting almost as many casualties on each other as the enemy. Fed up, Trochu ordered a withdrawal early the next morning.

“Civil War is a Few Yards Away, Famine a Few Hours.”

Trochu wasted no time informing the government that he refused to assume the responsibility for any new operations. It did not matter. Fairly or not, the government was through with him anyway, and relieved him of duty. Vinoy assumed command of the French forces in Paris. The rest of the government prepared to pursue peace with the Germans and appointed Favre to reopen negotiations with Bismarck.

In response, encouraged by anarchists and communists, Red elements within the Guard rose against the republic on January 22. Unlike October, the coup did not end peacefully. Fighting erupted between the Guard and the Mobiles outside the Hôtel de Ville. Only the timely arrival of Vinoy with reinforcements sent the Guard fleeing and prevented the disorder from spreading. Conditions within Paris had become intolerable. Rations were down to nine ounces per citizen. Unless the situation improved soon, revolution was imminent. Favre warned, “Civil war is a few yards away, famine a few hours.”

Armistice and Chaos

Two days later, Favre began negotiations with Bismarck. The major point of contention involved how many French soldiers could remain under arms. Bismarck demanded that all but two army regiments be disarmed, while Favre begged that the National Guard be permitted to retain its arms, fearful that a new rebellion would ensue should the government attempt to confiscate their rifles. Ever the realist, Bismarck warned Favre that the Guard would likely rise anyway, saying it would be in France’s best interests to keep more loyal soldiers armed to deal with the threat. Favre continued to insist. Bismarck relented, allowing the Guard to maintain its arms, but only one army regiment. Favre was satisfied. It was a diplomatic victory for which Paris would pay dearly.

According to the armistice terms, the French would pay a 200 million franc indemnity and surrender Paris’s perimeter fortresses. Signed on January 27, the stipulations took effect the following day, ending the siege of Paris. In total, the French had suffered an estimated 28,450 military and 6,251 civilian casualties, along with another 4,800 infant and elderly deaths. It was a bitter precursor of 20th-century total war. As a final gesture, Bismarck granted Favre’s wish that Paris fire the final shot of the siege. On March 1, the German army triumphantly paraded through the city.

Bismarck’s prediction came true 18 days later, when the French left rose against the government and established the Paris Commune. During the ensuing two months, more Frenchmen would die in the political infighting than had perished during the entire siege of Paris. It was a bitterly ironic conclusion to the heroic, if doomed, defense of the City of Light by patriotic citizens at both ends of the political spectrum.

“The heart of their nation, the city of Paris, had yet to fall, and honor dictated that until it did France must fight on.”

70 years later, the French no longer had that kind of determination, much to Hitler’s delight.

(My great-great grandfather was in the Prussian army in 1870. He never made it back to his home in Danzig, but to this day his descendants still live in the Gdansk area — and still speak German as their preferred language.)