By Michael W. Williams

Buried in the October 24, 1944, edition of the New York times was the headline: “German Ex-Officer Held as Nazi Spy: Captain in Kaiser’s Army, 62 and Foster

Daughter Accused of Sending Ship Data Before U.S. Entered War.” The article sketched a portion of the espionage careers of Simon Emil Koedel, a U.S. Army veteran, and his native-born foster daughter Marie Hedwig Koedel.

A Spy in the First World War

Born in Wurzburg, Germany, Simon Koedel immigrated to America in 1904 and traveled across the country before volunteering for the U.S. Army in October 1908. Soon after his 1911 discharge Koedel found work as a projectionist in movie houses. In November 1912, he became a U.S. citizen, taking the final oath in New York City. He met and married a fellow immigrant from Germany named Anna.

Koedel had been secretly sending shipping information to Germany when he decided he could contribute more by spying in England. He booked passage to Holland in April 1915, obtained an emergency passport, and sailed for England.

After snooping in Scotland and England he was arrested on suspicion of espionage in Liverpool and detained. British authorities deported him to the United States. Koedel sailed for Holland again in 1916 and made his way to Germany where he was commissioned as a captain in the German Army. Back in the States he bolstered his credentials as a loyal citizen by volunteering as a “Four Minute Man” to give talks to encourage patrons to buy Liberty Bonds.

Agent A2011 of the Abwehr

In the 1920s, Koedel and his wife took two orphaned siblings into their home, a five-year-old boy named Philip and a three-year-old girl, Marie. Koedel and his wife separated but did not divorce until 1933, when Koedel married Hulde Nelson.

Although Koedel’s mother had died, he and Hulde traveled to Germany in 1934, ostensibly to attend the Oberammergau Passion Play. Shortly after returning home, Koedel sent documentation of the services he had performed for Germany to Ernst Hanfstaengl. Known as “Putzi,” Hanfstaengl was a German-American and Hitler confidant who became Germany’s foreign press chief. Koedel followed this with a letter to Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels proclaiming that he and his family would remain loyal to Germany.

In 1935 Philip was sentenced to 71/2 to 15 years in prison for robbery. Koedel turned to Marie, an attractive 18-year-old, to further his espionage efforts. She sailed to Germany in July 1936 for Abwehr training.

After six months in Nazi Germany, Marie returned to New York. The Abwehr enrolled Simon Koedel as Agent A2011, the “A” indicating Koedel was a foreign agent. The “2” identified him with the Bremen sub branch soon to be headed by Johannes Bischoff, and the number “11” meant he was one of the first agents recruited for that network.

After Hitler’s 1936 occupation of the Rhineland, the head of Abwehr’s Section I, Major Hans Piekenbrock, reorganized his agents and designated the United States as a target of secondary importance. At the time America was a decidedly soft target. Koedel made good use of his time and his $200 monthly stipend. He recognized his lack of formal education in American English, written English in particular. Here is where Marie could help. She completed two years of high school and was a native speaker.

Koedel Infiltrates the Army Ordnance Association

Koedel applied for membership in the Army Ordnance Association (AOA), a trade organization for contractors for the U.S. military. AOA members had access to so much sensitive information that the FBI screened its candidates, but Koedel had not yet appeared on the agency’s radar screen. In August 1939 the AOA accepted Koedel.

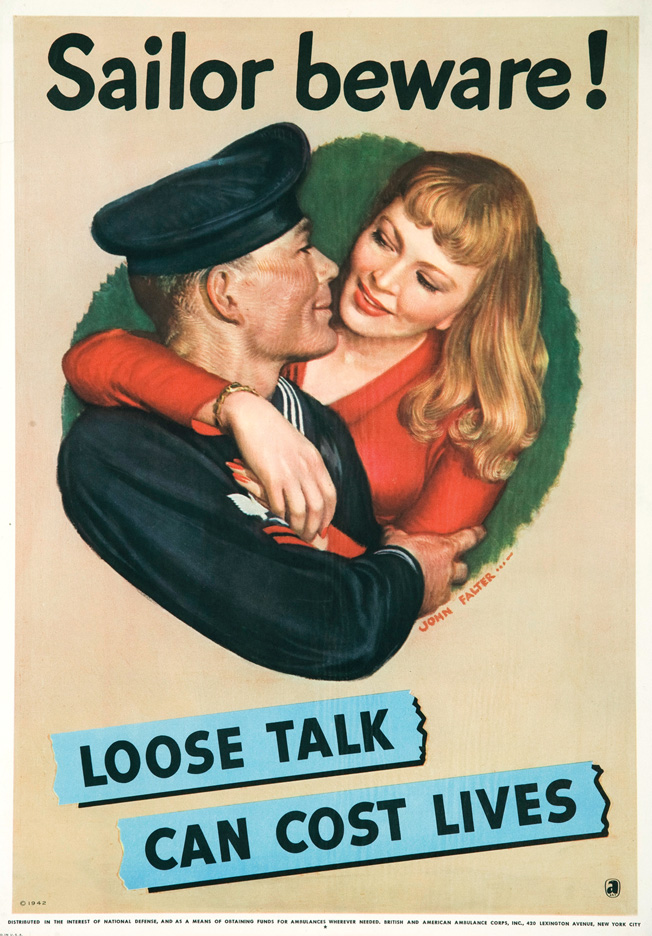

A few weeks later, Koedel received the cablegram he eagerly awaited. The message from “Hartmann” contained the word “alloy,” the coded combination that activated the Koedels as spies. As a projectionist, Koedel rarely worked a shift of more than five hours, and his work hours alternated, enabling him to vary his routine. Each day he brought to work a pair of pearl-handled binoculars, used to help sharpen the focus of films. They also came in handy during ferry boat rides if he wanted to read the names of ships.

Another factor that made Koedel an effective spy was his ability to glean valuable intelligence from mundane sources. One of Nazi Germany’s greatest intelligence coups had its origin in an article Koedel clipped from the New York Times. The story explained that a “scrambler” phone had been set up in a soundproof room in the White House basement to protect President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s transatlantic conversations. Roosevelt had used the phone since September 1. The enterprising Nikolaus Bensmann, one of Koedel’s Abwehr handlers, passed this information on. By March 1942 the Germans had a system that produced transcripts of transatlantic calls hours after an intercept.

The most crucial use of this technology took place on July 29, 1943, when British Prime Minister Winston Churchill phoned Roosevelt to discuss developments in Italy. The bloody Allied advance up the Italian boot can in part be traced Koedel’s work.

Koedel aggressively exercised his privileges as a member of the AOA. Members had to right to visit any U.S. munitions plants simply by showing their cards. However, when Koedel was turned away twice at the Army Chemical Warfare Center at Edgewood Arsenal near Baltimore, he called AOA headquarters, which protested to the War Department. On December 7, 1939, Koedel received a guided tour of the Edgewood Arsenal.

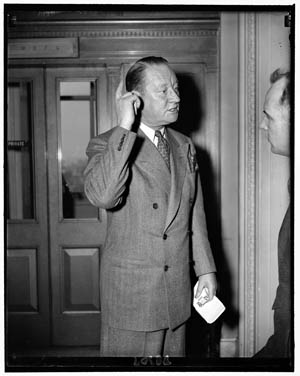

Attending AOA meetings allowed Koedel to meet administration officials and members of Congress. Senator Robert Rice Reynolds, a populist Democrat from North Carolina, had a seat on the Military Affairs Committee. Koedel convinced Rice to send him weekly reports from the State Department Munitions Board listing permits issued for exports of war materials to Britain.

Over 600 of Koedel’s reports got through to Bremen. Often Koedel walked into the German Consulate in New York and handed a white envelope to Robert Raehmel, an official who joined the consulate in 1939. Either Koedel sensed danger or Bremen warned him to discontinue this practice. His visits to the consulate ceased in early 1941. The Koedels mailed the bulk of their finds to overseas drops in Italy, Spain, and Portugal.

Simon Koedel: An Uncommon Kind of Spy

persuaded by Simon Koedel to share sensitive weekly reports from the State Department Munitions Board.

To a great extent Koedel’s success as a spy was due to the fact that he did not act like one. He did not employ aliases or false addresses; he often acted with boldness, and above all, he made no attempt to hide his love for Germany.

In the fall of 1939, Marie Koedel met John R. Walters. Likely, she was more attracted by Walters’s job at Republic Aviation than by his personal charms. In January 1940 Walters proposed. Shortly afterward, Marie broke off the engagement saying she and her father were German agents gathering information and that she could not interrupt their work.

Walters went to the FBI and was interviewed three times between February 14 and May 28, 1940. The FBI did not believe that his fiancée was a waterfront Mata Hari. In desperation, Walters telephoned the German Consulate in New York declaring he had told the FBI the Koedels were spies.

Koedel himself contacted the FBI in May 1940, when he strode into the New York field office to complain that a stranger told him that the FBI had a file on him. If this bluster was intended to show he had nothing to hide, Koedel overplayed that impression, penning several pro-German letters that were forwarded to the FBI by recipients.

Between June 1940 and May 1942, concerned citizens sent 14 of Koedel’s letters to the FBI. Unlike the typed, sober-minded letters in Koedel’s correspondence with the AOA, members of Congress, and defense contractors, these handwritten missives were riddled with errors in syntax and spelling.

Under Surveillance

In October 1941 the FBI put Koedel under surveillance, assigning Special Agent C. Lester Trotter to tail him. Koedel proved a slippery customer, changing transportation and loitering for long stretches of time.

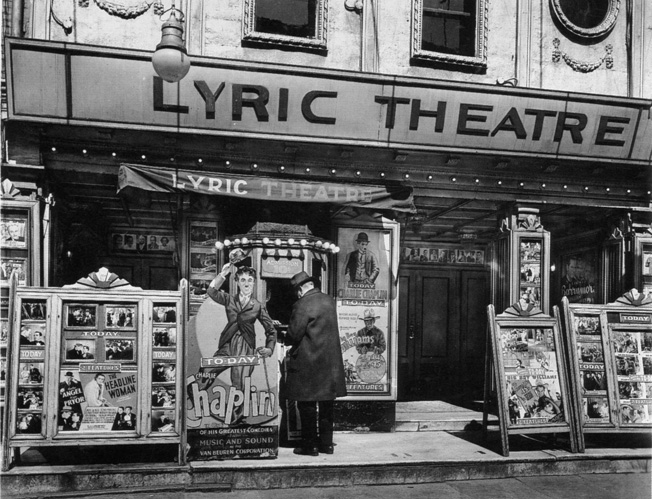

On Saturday the 25th, Trotter followed Koedel from the Lyric Theater with a rolled up newspaper tucked under an arm. He took the subway to Brooklyn and walked past dockyard warehouses before he stopped at a vacant store on Van Brunt Street and began fumbling with the latch. When Koedel turned back to the street the newspaper was gone. Trotter found the door locked. When Trotter returned to the abandoned storefront he found the door open with a man inside and two more outside dusting off an old automobile seat.

as a projectionist at the theater as cover for his spying on behalf of Hitler’s Third Reich.

Despite Koedel’s manner, his inordinate interest in shipping, and his use of a mail drop, the FBI did not pursue him aggressively until after Pearl Harbor. The FBI put Koedel under surveillance again because an interview of a former German Consulate employee had triggered renewed interest. The employee recalled a “Simon Coettel” who had visited the consulate and always left an envelope for Robert Raehmel. A 30-day cover of Koedel’s mail turned up nothing of interest. During eight days of surveillance, he never set foot near the waterfront. Abwehr records retrieved in Bremen after the war prove that Agent A2011 continued to submit reports through 1943.

A Case Without Evidence

Koedel revived the case against himself by writing Maj. Gen. Thomas A. Terry, head of the Second Service Command of the Eastern Defense Frontier. Koedel took issue with Terry, quoted as saying America’s cunning enemies would gladly use prostitutes to spread venereal disease among Allied soldiers. This letter prompted Terry to convene a meeting. He goaded the FBI into action, informing the agency of his efforts and forwarding a copy of Koedel’s letter.

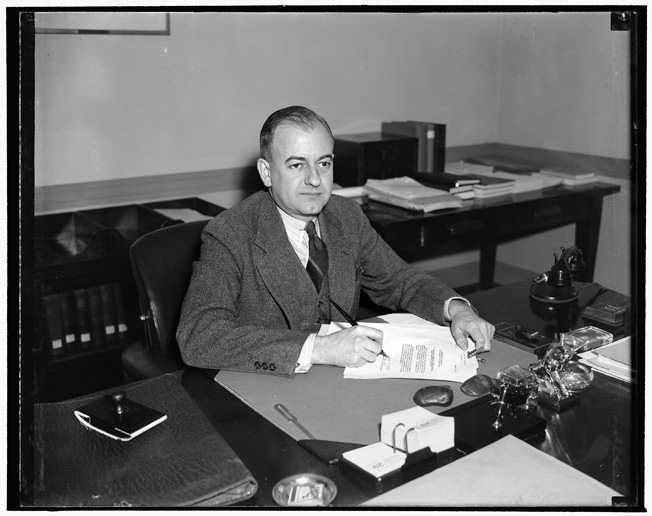

Assistant Director P.E. Foxworth assembled typed transcripts of all the Koedel letters sent to the FBI and recommended that the Attorney General’s office determine if his letters violated laws against sedition. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover sent the request to Assistant Attorney General Wendell Berge. Berge asked for additional investigation into Koedel’s activities.

In the fall of 1942, the FBI conducted a series of interviews with Simon Koedel, his family, co-workers, neighbors, and anyone who had reported his activities. The picture that emerged was of a tough man to pin down. Koedel denied that his activities had anything to do with spying.

Koedel carried what he called “a small pair of opera glasses” to keep projectors at the Lyric Theater in focus. His letters were written to provide “constructive criticism” and not to slander the U.S. Army.

Koedel agreed to an FBI search of his apartment, which turned up nothing. Instead of appearing for his next interview Koedel sent his lawyer, Charles Meisel, who said he had advised Koedel to cooperate because Meisel believed Koedel had not done anything wrong.

Agent Lawrence Brown again interviewed John Walters, who repeated what he had told the FBI in 1940. Walters produced several handwritten and one typed letter he had received from Marie. However, the FBI laboratory was unable to identify a match with any confirmed espionage correspondence.

Koedel’s Investigations Becomes Inactive

Saddled with witnesses deemed reluctant or unreliable and lacking documents to reinforce extensive circumstantial evidence of espionage, the FBI investigation stalled. Terry took matters into his own hands. On November 23, 1942, he informed the FBI that he planned to target Simon Koedel for exclusion from the Eastern War Frontier.

Following Koedel’s exclusion hearing in January 1943, Terry’s G-2 asked U.S. Attorney John F. Sonnett to charge Koedel with perjury for statements made during the hearing. Meanwhile, the FBI put the Koedel investigation on hold for three months.

There is an undertone of exasperation in Berge’s letter to FBI Director Hoover on March 17, 1943. Brushing aside Hoover’s request for further investigation of Koedel’s seditious activities, Berge insisted, “All possible investigative attention should be given to the strong indications that he has engaged in espionage.” Furthermore, he asked Hoover to send an FBI report referenced in Brown’s October report “and any other reports in this case not yet furnished to this Division.” Nearly a month passed before Hoover complied.

Berge reviewed the facts of the case and provided the FBI with a set of leads, which Hoover then forwarded to E.E. Conroy, special agent in charge of the New York office.

probe into Koedel’s activities.

By the time Conroy’s agents began to follow up Berge’s leads, Lt. Gen. Hugh A. Drum, Terry’s superior, issued an Individual Exclusion Order banishing Koedel from the Eastern Defense Command. Koedel left New York City for Martinsburg, West Virginia. Unable to obtain work in Martinsburg, he moved to Harpers Ferry.

The FBI investigation inched forward. Otto Borsdorf, the former German Consulate employee, identified Simon Koedel as the man who had provided Robert Raehmel with information. Nevertheless, on January 10, 1944, Conroy informed Hoover he was placing Koedel’s case in the inactive file.

Two Major Breakthroughs

Two and a half months slipped by, and then in his newspaper column Walter Winchell reminded his readers of the exploits of Walter Morrissey, a janitor at the German Consulate in New York City who had saved bundles of documents he had been ordered to burn. Turned over to the FBI, these papers helped convict seven Nazi spies. The day of the Winchell column, Tom C. Clark, Berge’s replacement as head of the Justice Department’s Criminal Division, sent Hoover a memo asking for developments in the Koedel case. In fact, the FBI was on the verge of two breakthroughs.

Just four days later, Conroy sent Hoover 17 documents from the German Consulate in New York. They included copies of letters to or from Simon and Marie Koedel, messages from the German Foreign and Propaganda ministries, and memos that referenced the Koedels.

Perhaps the most important document was an unsigned letter whose author claimed the Koedels were spies and that he and Marie made up some replies to recent inquiries. This document corroborated Walters’s testimony and explained why Borsdorf noted that Koedel’s visits to the consulate ceased in 1941.

The second breakthrough occurred in Los Angeles, where Special Agent Roy Barloga filed a report that established a link between Koedel and his German paymasters. Following the arrest of Abwehr agent Frank Jordan in Brazil, the FBI served a search warrant for papers owned by Ludwig Bischoff and stored in his father-in-law’s garage in Dallas. Agents found four checks issued to Koedel, the first marked “by order of Johannes Bischoff, Bremen.” The FBI knew Bischoff had briefed Jordan and sent him to Brazil.

What did not make sense was the timing of these revelations.The FBI had searched Bischoff’s papers in 1943. Five months ticked by before the FBI exploited the link established between a suspected spy and a known spymaster.

The Case Moves to Court

In late September, Conroy pointed out that if the Justice Department wanted to bring a charge of peacetime espionage it had to indict Simon Koedel by October 25, 1944, three years after Trotter observed Koedel on the Brooklyn waterfront and when the statute of limitations would expire. While Justice Department officials wrestled with whether or not to indict the Koedels, a third break came from an unexpected source.

Three painters were cleaning in the Lyric Theater when they came across some letters. One painter placed the items in an envelope, enclosed an anonymous letter, and mailed it to the FBI. The documents provided crucial evidence to bolster a case against the Koedels: a memo corroborated Walters’s testimony that the Koedels were gathering information on shipping; a letter signed “Nick” matched the signature of Herman Nicolaus Bensmann, another spymaster; and the address of an R.A. Hambourg in Milan, Italy, was a mail drop used by Waldemar Othmer, a convicted Abwehr spy. The evidence convinced Assistant Attorney General Clark to indict Simon Koedel. He left the decision to charge Marie to T. Vincent Quinn, U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of New York.

Quinn decided to charge Marie, and the indictment named Bischoff, Bensmann, and all other suspected spies named in the Koedels’ correspondence. One target proved too well connected to prosecute. The father of Bischoff’s wife was an Internal Revenue Service official, and her uncle’s brother-in-law was Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn.

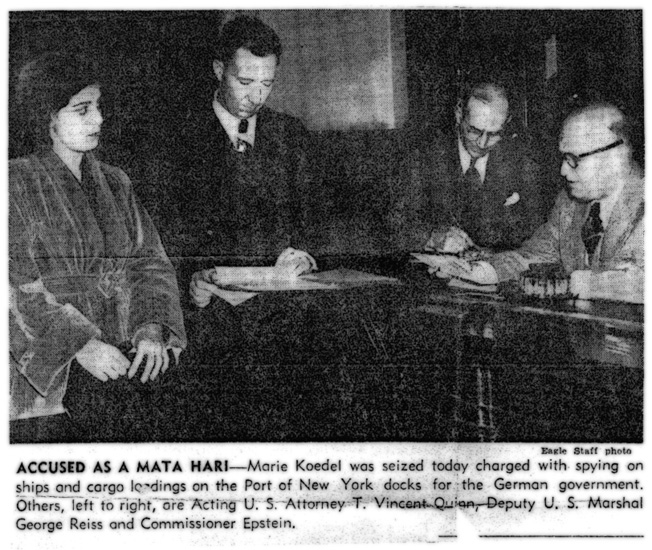

Agents arrested Simon and Marie Koedel on October 23, 1944, and accused them of violating the federal statute against peacetime espionage, a charge that carried a maximum penalty of 20 years in prison and a fine of $10,000. Both Koedels pled not guilty.

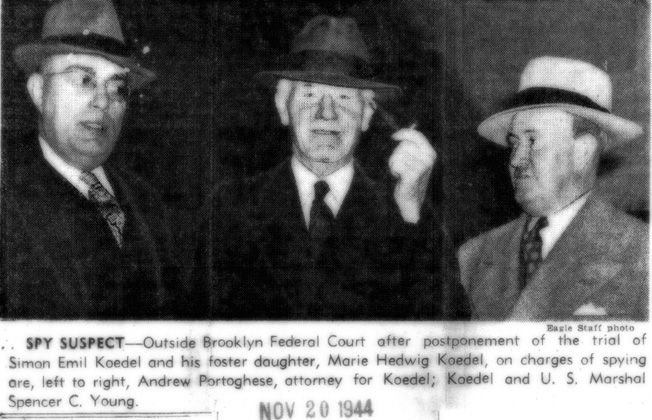

Koedel named Andrew Portoghese as his lawyer, but on November 9 Marie dropped her court-appointed lawyer in favor of Sanford H. Cohen. The trial was postponed for a week, but then on November 20 Marie changed lawyers again. Her new advocate, the blind John L. Coyle, got the trial rescheduled to give him time to prepare his case. Coyle’s new strategy was to question the sanity of Simon Koedel.

Convicted of Espionage

Justice Department prosecutors may not have minded the delays because their case was troubled. Two captured and convicted German spies refused to testify. That left the government with Trotter, the agent who tailed Koedel’s suspicious waterfront excursions; Borsdorf, the clerk who witnessed Koedel’s deliveries at the consulate; and Walters, Marie’s spurned lover whose stories the FBI had discounted as fantasy.

The prosecution was constrained by the decision not to call Bischoff into the courtroom. Furthermore, a crucial set of documents from the consulate, including a copy of Koedel’s letter to Goebbels, had been declared off limits.

The FBI tracked down the three painters who made the find. Sidney Rosen, the man who sent the materials, admitted he mailed them anonymously because he feared losing time from work if called to testify.

The trial began February 7, 1945. Assistant U.S. Attorney Albert V. DeMeo put Walters on the stand first. He claimed the FBI had asked him to “string along” with Marie to trap the defendants. If true, it was a subtle trap that took over four years to spring. Two witnesses testified to seeing Simon Koedel observing shipping.

On February 15, Portoghese announced that his client Simon Koedel was changing his plea to guilty, explaining it was in response to the testimony of the painters who had found letters in the Lyric Theater.

Marie’s lawyer was now free to portray Koedel as the evil stepfather. A weeping Anna Koedel testified that her ex-husband had been “very brutal.” Marie claimed Koedel beat her. Marie admitted she had written things for her father under duress.

The jury did not entirely buy her story. On February 20 it found Marie guilty of conspiracy to commit espionage. After returning the verdict the foreman told the judge that all the men on the jury and one of the women favored clemency for Marie.

On March 1, Simon and Marie Koedel stood before Judge Robert A. Inch. Looking dazed, Simon stared at the floor. He was sentenced to 15 years in federal prison. Marie was sentenced to 71/2 years.

The information the Koedels had sent lay for decades in the National Archives, a stone’s throw from FBI Headquarters, which contained files on a man named Walters who had walked into the New York FBI office in February 1940 with incredible tales about his lover and her stepfather.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments