By Donald Young

Following their impressive string of victories in Malaya, Hong Kong, Burma, the Dutch East Indies, and the Philippines, it appeared that the Japanese were invincible in the early days of World War II.

By the spring of 1942, the Japanese had driven the American and Filipino defenders of the Philippines to the Bataan Peninsula and the brink of total defeat. Still, they believed that it would take a major offensive to overwhelm the defenders. This belief actually forced them to design and successfully launch what could be called a near textbook version of the German blitzkrieg, surprising, cutting off, isolating, and bypassing enemy strongpoints. So effective was the campaign that twice during what turned out to be a six-day battle, offensive operations actually had to be halted to allow tanks and vital supplies to catch up.

The fact that the starving, emaciated, poorly equipped U.S. troops on Bataan were in such dire straits that they would never been able to stop the Japanese, blitzkrieg or not, is not pertinent to the story. Nor is the fact that Japanese General Masaharu Homma anticipated it would take a month to capture Bataan and that his decision to attack Mount Samat, the strongest position on the U.S. line, was a bold one. The plan of attack was central to the rapid success. It was one that would have made German General Heinz Guderian, known to history as the “Father of the Blitzkrieg,” proud.

Target: Mount Samat

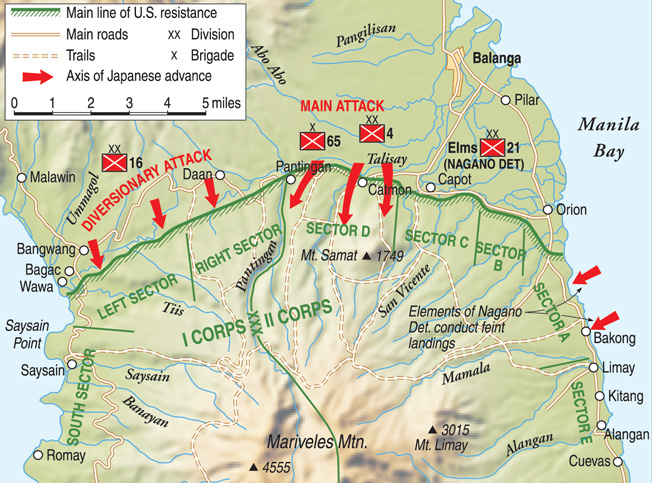

The U.S. defensive dispositions on Bataan left little doubt as to the focal point of the Japanese attack. Nearly the entire western half of the line, manned by troops of the U.S. I Corps, encompassed jungle so dense that it would not only neutralize the effects of Japanese air superiority but also swallow up an invading army within its roadless confines.

In contrast, with the exception of its most dominating feature, 300-foot Mount Samat, the eastern half, defended by II Corps, offered an open, jungle-free approach to its gently rising northern slopes. The area was accessible to the trails that flanked both the eastern and western sides of the mountain.

General Homma chose to launch his attack against Mount Samat, which he wrongly anticipated would take one week to capture, for two reasons. First, the Americans would least expect a frontal assault against the high ground that dominated the surrounding countryside. Second, with Mount Samat in Japanese hands artillery observers would be in position to direct fire for the primary assault down Bataan’s east coast. Prior to launching their assault on the mountain itself, the Japanese needed to gain control of three key trails, numbered 4, 6, and 429. Combined, these three trails encircled the footprint of Mount Samat.

Complete Japanese air superiority allowed the attackers to bomb and strafe virtually at will. Increasing air operations were the only indication that the renewal of Japanese offensive operations were imminent. Otherwise, there was little indication of exactly where or when the Japanese would strike the American line. To beef up the squadrons of light bombers and fighters already operating in the area, the Japanese brought in two heavy 60-plane bombardment units from Malaya and Indochina, plus two squadrons of Mitsubishi G4M Betty bombers and a squadron each of carrier-based bombers and Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters.

Neutralizing American Artillery

On March 25, the opening day of the pre-attack phase of the battle, Japanese bombers and fighters attacked targets without pause. The Japanese usually paused for three hours at midday; however, on this date they were literally in the air from dawn to sunset bombing and strafing U.S. frontline and suspected artillery positions.

For the next eight days, the cycle was repeated. On April 2, 1942, the day before the scheduled opening of the ground attack, 82 Japanese bombers pounded the forward slopes of Mount Samat, while fighters and dive bombers, directed by ever present spotter planes, made life miserable for the Americans and Filipinos squeezed into the defensive pocket on Bataan.

As with the German blitzkrieg, one of the major contributors to the success of the air phase was the use of spotter planes, whose accurate observation of American positions almost totally neutralized the effectiveness of U.S. artillery. Every time a 155mm or 75mm gun fired, coordinates from their smoke trails were radioed to either a patrolling fighter or bomber, which usually executed a quick and deadly response to the message.

The presence of the Japanese planes not only played havoc with artillery positions but also with infantry concentrations and machine-gun emplacements. One American officer wrote, “Every few minutes a plane would drop down, lift up a tree branch and lay one or two eggs. Every vehicle that tried to move, every wire-laying detail, infantry patrol, even individuals moving in the open were subject to these spot bombings.”

Captain Alvin Poweleit, a medical officer with the 194th Tank Battalion, wrote of his experience with marauding Japanese fighters. “We hit an open stretch of road just as Japanese strafers came over. Fortunately, we jumped out of the jeep in time to get out of the rain of machine-gun fire, but several soldiers were killed and many wounded. While dressing the wounded, the planes returned and laid another round of fire on us killing more. We tried to move the wounded to the side of the road, but again the bastards came back and bombed and strafed us. They continued strafing back and forth for about an hour.”

Artillery Pre-Attacks

For the artillery phase of the attack, the Japanese had close to 200 weapons, of which nearly half were heavy 150mm to 240mm guns. Most of these heavy guns were positioned within a rectangular, 41/2-square mile area west of Balanga, a mere three miles from U.S. lines and the forward slopes of Mount Samat.

With U.S. artillery nearly neutralized by the efforts of the ever present Japanese aircraft, the anticipated duels between the American 155mm guns and Japanese 240mm weapons never occurred. The Japanese also launched an observation balloon some three miles north of Balanga, well out of range of any operational American 155mm guns. Interestingly, the influence of the balloon was best noted in the diary of Major Achille Tisdale, an officer on Bataan commander General Edward P. King’s staff. In his entry for March 16, Tisdale routinely noted, “The Japanese now have an observation balloon.” Fifteen days later, however, he frustratingly wrote, “Nip artillery raising hell. If we could only get that damned balloon.”

To help conceal the scope and direction of their planned assault on Mount Samat, the Japanese limited their pre-attack artillery concentrations to eliminating U.S. artillery positions, the general disruption of troop movements, and destroying enemy command posts, communications, and defensive positions.

The third and perhaps most important pre-attack effort was to secure both flanks of the operation from possible counterattacks against the center or main focal point of the assault. Threats to both the east and west sides of the mountain would also force the defenders to direct their attention away from the main objective, thereby weakening the center.

Preparing for the Assault on Mount Samat

The Japanese preparations began in earnest on March 31, three days before the main effort, when the Japanese 16th Division to the west and the Nagano Detachment to the east began their operations. The 16th Division’s job was to engage the I Corps from its eastern boundary with the II Corps across its entire front to the west coast. At the same time, to further tie down and decoy the defenders, Japanese warships began shelling U.S positions from the South China Sea. While the 16th was keeping the I Corps occupied, the Nagano Detachment, made up of some 4,000 men from the 21st Division, began pushing down the East Road, while also creating a diversion with the feint of an invasion from Manila Bay south of the U.S. line.

With the primary assault scheduled for Friday, April 3, it was decided that the planned five-hour artillery bombardment in support of the direct assault would open at 10 am and continue nonstop until three in the afternoon, on the heels of which the tank and infantry would begin to roll forward. An hour before the ground action got under way, at 9 am, an estimated 196 Japanese artillery weapons, including 29 mortar and heavy batteries plus every close-support field piece available, would begin firing their guns, already registered on pre-selected targets. At the same time, Japanese aircraft, which by the end of the day would fly 150 sorties and drop an estimated 60 tons of bombs, would begin their assault on the chosen three-mile-wide U.S. front defended by the Philippine Army’s 21st and 41st Divisions.

A Raw Account of the Barrage

Captain Paul Ashton, a doctor with the 51st Division hospital high on the east slope of Mount Samat, had climbed to the brow of the mountain that morning to view the “sweeping panorama of flat farmlands … and the towns of Pilar and Balanga [from which] it [had been] possible to discern a great increase in the number of gun emplacements … around those two towns.”

Ashton continued, “On this day, a large number of guns were zeroing in on us and the muzzle flashes were plain to see. Then at 10:00 am, a greatly increased bombardment [came] in waves, steadily creeping up the brow and along the top of Mt. Samat. It continued for five hours and surpassed anything of the like we had ever seen. At the same time the Nips sent over fleets of bombers … the explosions [of bombs along] with the whine of smaller strafing planes … was [sic] almost deafening. Communication lines and artillery positions were destroyed. Several acres of brush caught fire and burned fiercely.

“It became worse with each hour.… I climbed the hill to the top of Samat for the last time to see what happened. I was amazed to see that the topography had changed. The trees were a jumbled mass of foliage; fire was burning the dry brush at the base and creeping up the front of the hill. A few bodies could be seen scattered along Trail 4, the main [withdrawal] route from the front, and groups of Japanese were fanned out everywhere.

“The extensive denuding of the area must have meant that most had withdrawn in units as the barrage crept upward and across the mountain. I found the answer later [when] I drove our only ambulance over trails leading southward from the 51st and 21st Division areas. I was greatly hampered by roads full of aimless stragglers pouring toward the south.”

“The Most Devastating Concentration of Enemy Fire”

Recorded effects of the bombardment were consistent throughout the command. Captain Carlos Quirino of the Philippine Constabulary’s 2nd Division remembered it as “the most devastating concentration of [enemy] fire seen during the Philippine campaign.” Had he known, he could have added, “and the entire Pacific War to come.”

Although it may have seemed to those men along the II Corps front as though the entire line was being blasted simultaneously, the Japanese were actually directing the bulk of their air and artillery bombardment toward one specific point.

Sector D, the westernmost portion of the II Corps’ area of responsibility and widest of the four sectors, stretched some three miles across the lower slopes of Mount Samat. Divided roughly in half, the defense of the sector was shared by two Philippine Army divisions, General Mateo Capinpin’s 21st Division on the east and General Vicente Lim’s 41st Division on the west. Both generals had assigned all three of their regiments to the line. General Lim had his in numerical order from left to right. The Japanese directed their assault at the 1,000-yard-wide defensive perimeter manned by the 42nd Infantry Regiment, 41st Division.

Despite the initial pounding of the 42nd frontline positions by the Japanese artillery and aircraft, the Filipino soldiers of perhaps the toughest of the Philippine Army divisions on Bataan did not budge. After riding out over two hours of steady bombardment, the Americans and Filipinos paid little attention to the next squadron of enemy bombers that came over until the usual “freight train” roar of falling high explosives strangely did not occur.

As the Filipino soldiers cautiously looked up from their holes to see what was happening, they saw what looked like hundreds of stick-like objects falling from the sky. When these sticks hit the ground, they burst into flame. They were firebombs, incendiaries.

Firebombing on the Philippines

It was the end of the Philippine dry season. The flat lower slopes of Mount Samat were devoid of lush tropical jungle but overgrown by brush and dry clumps of bamboo and uncut sugar cane. It was not long before hundreds of small fires started by the incendiaries, fanned now by an afternoon breeze, merged into one.

As the heat grew in intensity, men were flushed from their frontline positions back across a cratered, lunar-like landscape toward their regimental reserve line. Although it was possible to outrun the fire, continued heavy Japanese artillery fire forced the Filipino soldiers to seek refuge in shell holes or abandoned foxholes along the way.

Soon, there appeared to be no escape. Panic stricken, those who tried to outrun the fire were killed by the enemy artillery. Just as many of those who stayed to avoid the artillery burned to death.

Sergeant Silvestro Tagarao of the 42nd Infantry, whose Company K occupied the outpost line on the leading edge of the regiment’s defensive positions, recalled the deadly effect of the attack and firebombing. “The enemy [opened] up with a mortar barrage. We knew that the much-awaited assault was on. We dashed into our foxholes and waited eagerly,” he recalled. “Violent explosions came rapidly, blowing up the trees around us. The merciless barrage went on but there was no reply from our guns.”

“At the height of the intense fire, incendiary bombs [were dropped],” he continued. “They came unannounced, going up with a silent blast that became hot, blinding fire that burned the woods and rendered our position insecure. [Soon] the fire was all around us and we couldn’t hold there anymore. We waited for an order from our C.P., but none came.

“Soon flames were very close to us. We came out of our foxholes and withdrew. One of the men told me that our left flank had been consumed by flames several minutes before. Again we had to move back because of the flames, moving further until we reached our command post. It was also burning, and nobody was there except a corpse lying on a stretcher.”

Unexpected Success

At 3 pm, the line, masked in dense smoke and racked by steel and fire, was hit again. This time, General Akira Nara’s 65th Brigade supported by the 7th Tank Regiment attacked. The objective of Nara’s thrust was Trail 29—the feeder trail to 429, which, along with Trail 6 on the west and Trail 4 on the east side of Mount Samat, encircled the high ground.

Like a rampaging river, the rout of the 42nd Infantry flowed into the 43rd Infantry on its right, carrying most of the 43rd with it. General Nara, who at best had expected to get only as far as the U.S. main line that day, surprisingly found a 1,600-yard-wide corridor completely abandoned to him when he arrived later that afternoon.

At the same time, one mile to the east, the 4th Division’s 61st Infantry supported by a dozen tanks launched its attack against empty foxholes previously occupied by the men of the 43rd Infantry. When the battle subsided around 6 pm, nearly two-thirds of the enemy’s initial objective, the capture of the junction of Trail 6 and 429, had been accomplished. At the point where Trails 6 and 429 reached the backside of Samat, 429 turned eastward to connect with Trail 4. The Japanese were nearing their objective of cutting off Mount Samat from the rest of the Allied defensive positions.

Buoyed by their unexpected success on the first day of the ground attack, the Japanese resumed the offensive at 6:30 the next morning with the same intensity as the day before. The Japanese kept the pressure on Mount Samat’s west slope and hit General Mateo Capinpin’s 21st Division on the Allied left wing. After a two-hour air and artillery bombardment, the 21st Infantry, westernmost of Capinpin’s three regiments, was hit by infantry and tanks of the 7th Tank Battalion. The Japanese ran rampant through the helpless Filipinos.

Six Days of Battle

By 9 am, less than three hours after the first bomb dropped, the Filipino 21st and 23rd Regiments were driven off the main line. The 22nd Infantry, positioned astride the access to Trail 4, was forced back an hour later. In less than a day and a half, the Filipinos had abandoned a three-mile-wide sector in front of Mount Samat.

April 5 was the third day of General Homma’s anticipated 30-day offensive to capture Bataan. However, thanks to the effective blitzkrieg against Mount Samat, the Japanese were halfway home. The battle for Bataan would be over in six days.

The objective of the Japanese this Easter Sunday was the capture of Trail 4, thus completing the encirclement and isolation of Mount Samat, securing its heights, and allowing the capture of the entire Bataan Peninsula to proceed.

After consolidating their seizure of Trails 6 and 429, the Japanese forces on the right began their assault on the western slope of the mountain. They found the going relatively easy. In fact, by 1 pm, less than three hours later, they had reached the heights. Before the Japanese gains could be consolidated, however, the stoutest defense so far was put up by U.S. artillery as accurate fire erupted from the guns of the 41st Field Artillery located on the south or reverse slope of the mountain. Until their forward observers were forced from their positions on the heights, the American artillerymen were able to direct fire from their Model 1917 British wooden-wheeled 75mm guns and old Vickers 2.95-inch pack howitzers. The defensive artillery fire held up the Japanese assault on Trail 4 until reinforcements arrived later that afternoon.

Disgrace and Execution for Victorious General Homma

By about 4:30 pm on April 5, with the capture of Mount Samat and control of Trails 429, 6, and 4, the Japanese had successfully executed their own version of the blitzkrieg. During the remainder of the Pacific War, they were never again presented with the opportunity to mount such an offensive against the Allies. When the Bataan Peninsula fell on April 9, 1942, the remnants of the American and Filipino defenders were forced to take refuge on the island of Corregidor in Manila Bay. Their days were numbered.

General Homma was never credited with developing the tactics of the successful attack. His conquest of the Philippines had fallen behind the time table established by the high command in Tokyo. A more rapid operation had been anticipated following the three-month victory in Malaya and Singapore. The capture of the Philippines required six months of fighting, a sharp contrast to the lightning movement against Bataan.

Homma was relieved of command in June 1942 and brought home in disgrace. He retired from the military in 1943. Convicted of war crimes related to the brutality of the Bataan Death March and the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, Homma was executed by firing squad in 1946. n

Donald Young writes from his home in Vista, California. He has done extensive research on the Pacific War with particular interest in the fighting in the Philippines.

My grandfather was Brig. Gen. Allan C. McBride and was involved in the Philippines. He died as a pow in 1944. Wish I could know more about his involvement in the fall of the Philippines.

My Father Lt. Andrew C. Mc Bride was involved in the invasion as a member of the 511th PIR in 1945.

It was a very interesting part of the war. I had the opportunity to visit Mt Samat and surrounding area over the last 4 years. My wife grew up in Balanga and her grandmother still remembers part of the occupation when she was a young child. I wish I had more time to go back and explore. Thank you for your family’s service. Mine 37 years in the Navy, retired in 2019.

Not quite. The defenders of Bataan had already been holding out for over 2 months. Food and ammunition had been rationed for a long time. They and their undertrained Filipino allies had been hoping and waiting for the relief shipments that never came. By march they had been on half rations for some time, monkey meat was a rare treat. They held out for over 3 months. Not sure if Guderian would have been too impressed