By Robert L. Swain

On a sweltering evening in early July 1553, the late King Henry VIII’s only legitimate son, the sickly 15-year-old Edward VI, died an agonizing death from tuberculosis, possibly complicated by measles. Edward’s largely unmourned passing was followed by a self-serving scheme by his royal protector John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, to maneuver his 15-year-old daughter-in-law, Lady Jane Grey, onto the throne instead of Mary Tudor, the only surviving offspring of Henry’s first wife, Catherine of Aragon.

Arguably the most powerful man in England, the 51-year-old Northumberland had based Lady Jane’s distant claim to the throne on the fact that she was Henry’s great niece. That said, the claim contravened Henry’s will, which had called for the crown to go first to Edward, then to Mary, then to Elizabeth, and last, to the heirs of his younger sister Mary (Lady Jane Grey being one of her granddaughters).

Still, Northumberland had manipulated the dying Edward into naming Lady Jane his successor by preying on Edward’s fears that his Catholic half sister Mary would overturn his efforts to ensure that the country remained Protestant. Then the duke intimidated the Privy Council into proclaiming Jane queen several days later. Accordingly, she was installed by her father-in-law in the royal suite at the Tower of London to prepare for her coronation. But Northumberland had not taken into account the public’s reaction, which turned out to be decidedly unenthusiastic about Jane.

The Privy Council grew uncertain about its hasty proclamation when pockets of active resistance to Jane began to emerge in various areas, first slowly and then more rapidly. The council’s so-called firm support for her began to unravel. Alarmed, Northumberland moved aggressively to suppress the dissidents, but his forces lost heart at the prospect of armed skirmishes, and the suddenly revived council moved quickly to avoid being on the wrong side if Mary’s contravening claim to the throne prevailed. Council members ordered Northumberland’s arrest, and he was taken into custody a day after Lady Jane Grey’s nine-day reign collapsed.

At the same time, Mary Tudor, 37, safe with her household staff at Framlingham Castle in Norfolk, was persuaded by her rapidly growing number of supporters to ride into London to claim the throne. An exhilarated Mary, loved and scorned with seemingly equal fervor by her father, arrived in London on August 3 amid a jubilant crowd of supporters. A staunch Catholic despite her father’s break with Rome years before, Mary decided to make an emotional early pilgrimage to the Tower of London to free the “martyrs” put there by her late father for persisting in their Catholic faith.

Freeing Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk

One of the first prisoners to greet Mary at the Tower was the former Duke of Norfolk, crusty 79-year-old Thomas Howard, a survivor of six years of confinement. Despite his reputation as a tough, resilient commander of Henry VIII’s armies, Howard was physically small and had been suffering from rheumatism and a finicky stomach for years. Once a key member of Henry’s inner circle and uncle to two of Henry’s wives (Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard), Howard had been sent to the Tower in December 1546 for allegedly conspiring with his headstrong son, Surrey, to tamper with the succession during the waning days of the irascible Henry’s reign.

While both Howards had been found guilty on flimsy evidence, Norfolk had confessed, hoping for mercy. The king would have nothing of it, and Surrey was beheaded on January 19, 1547, with his father scheduled soon to follow. However, Henry obligingly died nine days later, just six hours before the duke was scheduled to be executed. When the Privy Council got around to thinking about it, they reached the consensus that confinement in the Tower at such an advanced age would carry away the old duke without staining their hands with his blood. Later, some would rue their reluctance.

Among Mary Tudor’s first official acts as queen was to see to it that Howard’s dukedom and Order of the Garter were restored, and monies were granted him to buy back some of his personal property sold off during the reign of her half brother, Edward. Then Mary announced her intention to marry Prince Philip, son of Charles V, emperor of Spain and the Low Countries, who was 10 years her junior.

The Rebellion of Sir Thomas Wyatt

Blissful over her choice, Mary did not pick up on the instantaneous rumblings caused by word of her planned wedding. After listening impatiently to advice from the seldom-convened Great Council, a shaken Mary regained her composure in Tudor fashion by adjourning the group. Still, lobbying against her marital choice persisted for weeks, with intermittent acts of vandalism taking place in protest of the wedding.

Virtually unnoticed at first, conspirators had begun meeting in London as early as November to plot a rebellion. One of their leaders was Sir Thomas Wyatt, son of the famous poet of the same name who had been a one-time suitor of Anne Boleyn. Although the younger Wyatt had voiced support for Mary in July, he utterly detested anything Spanish, and his enthusiasm for the new queen soon soured. Gathered around Wyatt were other equally disgruntled nobles. Barely more than a limited conspiracy at this point, the plotters intended to stage simultaneous uprisings on Palm Sunday in Herefordshire, Devon, Leicestershire, and Kent, where Wyatt lived in the 13th-century Allington Castle, on the banks of the Medway River.

Conspiracies were hard to conceal in Tudor England, with informers everywhere, and Mary and her council were soon put onto what was afoot. Informants told the council specifically about Wyatt recruiting adherents. Although initially shocked, Mary recovered quickly, calling on officials of the City Corporation for support and funds. But few seemed sure of Wyatt’s declared purpose, and they underreacted to her anxiety. Whether it was their low opinion of the queen or their distaste for Mary’s choice of a husband, corporation members scraped together only enough money to arm a paltry force of 500 men-at-arms.

Norfolk Assembles an Army

Mary, undaunted, turned to the matter of selecting someone to rally and lead her forces against Wyatt. The only noble Catholic personage with military experience trusted by Mary was the newly restored Duke of Norfolk, now 80. Improbable as it may seem, Mary entrusted command of her assembled troops to someone who, years before, had browbeaten her to forsake her mother and accept her father’s marriage to Anne Boleyn, even telling Mary that, if she were his daughter, he would “smash her head against a wall until it was soft.”

While Norfolk was the logical choice to head Mary’s forces, he had doubts about the adequacy of the small force being assembled. His first question was in the form of a complaint over how effective a mere 500 men-at-arms could be against several thousand rebels in Kent. Called upon over the years by Henry VIII to lead campaigns against rioters, rebels, and enemies at home and in France, Scotland, and Ireland, Norfolk had so irritated the king with his incessant complaining about inadequate support that Henry had turned to more compliant commanders to serve him.

In this instance, the best Mary could do in response to Norfolk’s harangue was to offer her 200 personal guards, presently under the command of Sir Henry Jerningham, to serve under Norfolk as his captain of the guard. His sense of honor restored, Norfolk continued to grouse about the number and quality of the men in his command. At the same time, Norfolk made a mistake by choosing to ignore rumors that some of his troops planned to go over to Wyatt’s side. This sort of thing had never happened under his command before, and he probably considered it a ploy to weaken his resolve.

Norfolk rose to the occasion. He ordered supplies, requisitioned artillery from the Tower, and prepared to move southeast against the rebels, known to be centered in the old city of Rochester, 24 miles away. Soon after departing London in late January 1554, the old duke received word that some of Wyatt’s men had seized the bridge over the Medway River near Rochester. This prompted the duke to send a herald ahead to open negotiations with the rebels to implement the queen’s recent promise to grant pardons to all who would give up their rebellious claims.

A Lack of Reinforcements

Unfortunately for Norfolk, the dissidents in Kent recognized the herald’s offer to negotiate for what it was: a ploy to lull them into laying down their arms. The rebels were skeptical of anything emanating from Norfolk and ignored the offer, claiming they had done nothing for which they needed a pardon.

Too experienced to be surprised by the reaction of the rebels, Norfolk continued his march in near-freezing weather toward Rochester; his men were bundled in white coats with red crosses and divided into six companies. The force came into sight of Wyatt’s position below Spitell Hill, where the road runs down to the bridge over the Medway. Norfolk instructed his company commanders to besiege the bridge and provoke Wyatt’s contingent into yielding.

Norfolk’s confidence in being able to take the bridge rested on an expectation of reinforcements from the command of his much younger half brother, Lord William Howard, now serving as Mary’s lord admiral. The duke should have known better than to rely on William, who had never forgiven him for not supporting family members after the scandal of Catherine Howard’s unfaithfulness to Henry VIII. When evidence of her premarital sexual escapades surfaced, many of the Howards were held accountable for not revealing Catherine’s wanton indiscretions to the king. Norfolk, who had helped engineer the marriage, had withdrawn to his ducal estate at Kenninghall to avoid the worst of Henry’s wrath, while William Howard and others had to endure several months’ imprisonment in the Tower.

When reinforcements failed to appear, Norfolk’s optimism faded, but he continued his plan to subdue or placate the rebels, sending a message to the Privy Council in London pledging to do his best. For the moment, the message reassured Mary and the worried council members, some of whom could still recall stories of Norfolk’s tenacity in face of unfavorable odds in France and Scotland, where he and his father, although gravely outnumbered, had achieved a brilliant victory 40 years before at the Battle of Flodden.

“We Are All Englishmen! A Wyatt! A Wyatt”

At the Medway Bridge, Norfolk was outnumbered at least 14 to 1, despite the late arrival of Lord Abergavenny with the several hundred troops he had raised for the queen. Shortly before Abergavenny’s arrival, word had arrived that sailors from ships riding at anchor below Gravesend to escort the queen’s groom to London had gone over to Wyatt. With only the faintest hope that more reinforcements might be found, Norfolk told his officers he was prepared to give battle if Wyatt decided to send his men across the bridge.

Ordering his men to stay behind, Norfolk rode forward with Jerningham to see where to place their guns for maximum effect, should artillery support become necessary. Satisfied that he knew what had to be done, Norfolk ordered forward his gunners and men-at-arms. When this was accomplished, the duke threw caution to the chilly winter winds and gave the order to fire. As the first gun belched forth, Alexander Brett, one of Norfolk’s captains, drew his sword and startled the duke and Jerningham by shouting as loudly as he could: “We go about to fight against our native countrymen and friends in a quarrel unrightful and wicked! We are loyal Englishmen all, resisting the proud Spaniards who make the English slaves, spoil our goods, ravish our wives and deflower our daughters!”

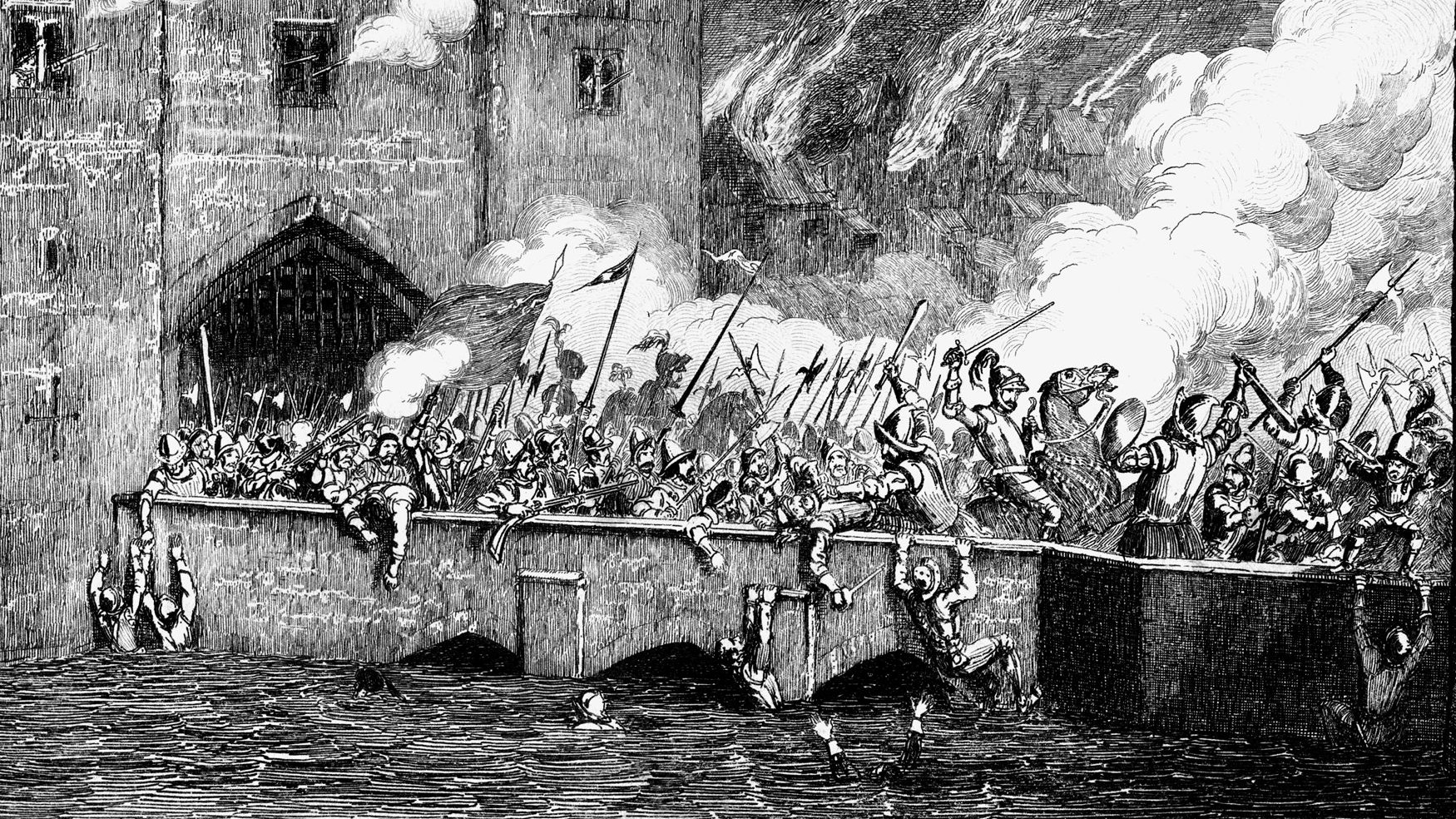

With these words catching everyone’s attention, Norfolk watched something he had never seen before: a royal force breaking ranks to join the other side, shouting: “We are all Englishmen! A Wyatt! A Wyatt!” Nothing like this had happened since the Wars of the Roses a hundred years earlier. Norfolk sat motionless on his horse, still disbelieving the flight of the men over the bridge to the rebels’ side. When younger, he might have ordered his field pieces aimed at the deserters, but instead Norfolk simply pulled his horse’s head around and galloped off. Norfolk’s failure to hold his force mocked his earlier pledge to die for the queen, but as one historian remarked later, “Norfolk lived as long as he had because he never found anything worth dying for.”

The defection of Norfolk’s “Whitecoats” at Medway Bridge allowed Wyatt to turn his attention toward London. After conferring with his captains, he ordered his forces to follow him there. Along the way, Wyatt elected to ignore Sir Richard Southwell’s force at Maidenstone, but he did pause to lay siege to nearby Cooling Castle, near the mouth of the Thames, which was being held without much determination by 58-year-old Lord Cobham, who was Wyatt’s uncle.

“They Won’t Come in Here!”

Within days, a heartsick yet angry Queen Mary witnessed a bedraggled Norfolk and his handful of officers straggle back into London without supporting forces or artillery. When Mary turned to the Privy Council for advice and help, she found the mood ugly, something that didn’t change when a mere scattering of Norfolk’s soldiers appeared weaponless in London with their white coats torn and dirty.

Approaching London’s outskirts, Wyatt’s expanded force skirmished with small detachments of royal guards. Word of the fighting prompted Mary to publish a call for public support; within hours people assembled to hear the queen. When she arrived, the crowd grew silent as Mary spoke bravely and with more confidence than she might have felt. She promised her listeners that Lord Norfolk would defend the city “from spoil and sack, which is the only aim of the rebels.”

Mary had little else to offer her subjects. Shortly after her speech, the lord admiral managed to stiffen the resolve of defenders at Ludgate, shouting, “They won’t come in here!” He ordered his men to cut loose the drawbridge at London Bridge. To everyone’s surprise and relief, Wyatt’s resolve unraveled in the outermost streets of London. In fitting turnabout, Jerningham took the rebel leader prisoner.

Pardoned Deserts, Wyatt Beheaded, and a Quiet Death for Norfolk

Norfolk, alternately shocked and depressed by the experience at Medway Bridge, asked Mary for permission to withdraw to his beloved estate at Kenninghall. The queen granted the request all too readily, giving Jerningham the responsibility for rounding up the men-at-arms who had gone over to Wyatt and his rebels. Arrested quickly, 100 of them were tried within days, found guilty of treason, and hanged from the very doors of their homes in London. The rest were taken bound and wearing nooses around their necks to the tiltyard at Westminster to appear before Mary. It was reminiscent of the apprentices being paraded before her father in 1517 after the Evil May Day riots, which had been suppressed by Thomas Howard and his father. Like Henry VIII, Mary pardoned the deserters. The unfortunate Wyatt, however, was held in the Tower until April, when he was taken out to Tower Hill and beheaded. Shortly afterward, the now retired Norfolk’s younger brother William was created Baron Howard of Effingham for his defense of London during the recent rebellion.

As preparations for Mary’s marriage to Philip of Spain were renewed, Norfolk, not accepting full retirement, resurfaced to express his concern over how to ensure the marriage would be respected. Mary did not appreciate his anxieties. By the time of the wedding in late July, Norfolk was too frail to attend the long ceremony. He died quietly in his sleep on August 25, while the queen and her husband honeymooned briefly at Windsor. In deference to the deceased lord, they cancelled their social calendar for a day.

Age had accomplished finally what enemies, competitors, pestilence, a death sentence, and long isolation in the Tower had not been able to manage. Norfolk had outlived virtually all his contemporaries and all his children except for one daughter. Few could recall firsthand his one-time prominence as lord admiral, viceroy of Ireland, leading general, war hero, or principal adviser to Henry VIII.

The old duke was buried and mourned by a handful of family members, including his second wife, the haughty daughter of another prominent duke, who was long estranged from him because of his cohabitation with a longtime mistress who had disappeared from the scene when he was sent to the Tower. Years later, Norfolk’s grandsons built a magnificent marble tomb for him in the small church next to Framlingham Castle. Nowhere in the small church is there any mention of Norfolk’s last command.

Join The Conversation

Comments