By Michael D. Hull

Laden with 500-pound bombs and incendiaries, 10 Japanese twin-engine Mitsubishi Ki21 Sally bombers took off from the Hanoi airfield in Indochina on the morning of Saturday, December 20, 1941.

Beginning a 300-mile flight to Kunming, the China terminus of the Burma Road, the Japanese pilots anticipated a routine mission. They had been bombing the Chinese city on clear days for a year. The bombers had no fighter escort and had never needed one because the Chinese had neither fighter planes nor antiaircraft guns with which to oppose them.

On this day, the Japanese crews planned to fly unopposed over Kunming at an altitude of 6,000 feet in a stately, deadly procession. But, unknown to them, a highly effective “jing bao” early-warning system had been developed, and observers huddling in caves several miles out around Kunming were listening for enemy planes.

When the Japanese pilots were about 30 miles southeast of Kunming, they suddenly saw something they had not expected— four fast fighter planes bearing down on them. Nicknamed the Panda Bears and led by Lieutenant “Scarsdale Jack” Newkirk, they were shark-nosed Curtiss P-40 Tomahawks of the newly formed American Volunteer Group, the Flying Tigers.

The Pandas and a few more P-40s closed on the enemy formation, raked it with machine-gun fire, and shot down four bombers. The surviving Mitsubishis jettisoned their bombs and turned back for Hanoi. No Tomahawks were lost, and the young American pilots zoomed back to Kunming, where they triumphantly did slow victory rolls over their airstrip.

“Next Time, Get Them All”

It was the first combat sortie for the Flying Tigers, and their spirits were raised further when they learned from later reports that three more of the enemy bombers had failed to return to base. The American volunteer fliers listened to words of both praise and criticism from their jut-jawed, craggy leader, Lt. Col. Claire L. Chennault, and then he added dourly, “Next time, get them all.”

Three days later, on December 23, 1941, a dozen Tomahawks of Lieutenant Arvid Olson’s Hell’s Angels squadron joined stubby, antiquated Brewster Buffalo fighters of the British Royal Air Force’s No. 67 Squadron to tangle with a formation of Japanese bombers heading across the Gulf of Martaban to Rangoon, Burma. Five bombers and four enemy fighters were downed, but one Flying Tiger was shot down and another forced to bail out. Chennault considered it a bad trade, for he had too few pilots and P-40s at his disposal.

On Christmas Day, 1941, the 12 operational Hell’s Angels and 18 RAF Buffaloes encountered 71 Sally bombers escorted by between 30 and 40 fighters. The Tigers had learned well their lessons from Colonel Chennault and sliced methodically through the enemy force in pairs. One after another, Japanese bombers were shot down. That day, 32 enemy planes were claimed for the loss of two Tomahawks and no pilots. Seven of the claims were made by RAF Buffalo pilots. The AVG produced three aces in the process, setting a record for kills in one day that they would not surpass.

Aerial action continued around Rangoon, so Chennault dispatched his Panda Bears to relieve the Hell’s Angels. In the first 10 weeks of combat, the Flying Tigers dueled with enemy planes 31 times over Burma. They claimed 217 Japanese aircraft downed and another 43 probably destroyed, for the loss of 16 P-40s and six pilots. Chennault rotated his Adam and Eve Squadron to Mingaladon to share in the action as the RAF, meanwhile, replaced its tattered Buffaloes with more deadly Hawker Hurricanes.

The Only Mercenary Air Force of World War II

In action for only seven months, from December 1941 to July 1942, and with never more than 50 pilots on call at a time, Chennault’s Flying Tigers outfought their Japanese foes in the skies over southern China and Burma and racked up an extraordinary record of victories. During those frenzied months, the American fliers claimed 297 enemy planes destroyed, up to 240 unconfirmed kills in the air, and 40 planes destroyed on the ground. Four Tigers were lost in air combat, six died from ground fire while strafing, three perished in training accidents, three to enemy bombing raids, and three were taken prisoner. Twelve Tomahawks were destroyed in the air, and another 61 were written off in training mishaps, were destroyed on the ground by the enemy, or were set afire when the Tigers had to hurriedly evacuate their airstrip at Loiwing on the Burma-China border.

In the few months while their unprepared nation was recovering from the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, the men of the AVG—the only mercenary air force in World War II—grabbed the public imagination and held it. Daring in the sky and flamboyant on the ground, Colonel Chennault’s Tigers found their exploits being amplified in newspapers, radio broadcasts, magazines, comics, and eventually books and motion pictures. They were the Lafayette Escadrille or Eagle Squadron of the Far East, providing a major lift to home-front morale when American fortunes were at their lowest.

But the fact that so much well-timed morale-boosting and effective combat flying was being done so early in the Pacific war had nothing to do with American foresight—quite the opposite. Strategic policy in the U.S. Army Air Corps during the 1930s had been dominated by the “invincibility” of the heavy bomber, and Chennault—an original thinker in pursuit aviation—spent more than five frustrating years working to build an air force for Nationalist China after leaving the Air Corps in 1937. He maintained that well-led squadrons of fighters could stop a large force of bombers, as Royal Air Force Fighter Command would prove in the skies over southeastern England in the summer of 1940.

“I Have Tasted of the Air”

Claire Lee Chennault, the founder and leader of World War II’s most colorful air unit and one of the engaging, egocentric characters in which the China-Burma-India Theater abounded, was born in Commerce, Texas, on September 6, 1890. He was of French Huguenot descent and was a distant relative of Texas hero Sam Houston and Confederate General Robert E. Lee. Claire spent an idyllic and Tom Sawyerish boyhood in Louisiana, studying for 18 hours a week at a one-room school in the bayou town of Gilbert. Slender, dark-haired, and with an olive complexion, he was a quiet, reserved boy and a good student.

In January 1909, he matriculated at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. He drilled with the ROTC, competed in track, baseball, and basketball, and farmed a cotton patch to earn money for his sophomore year. But when his beloved stepmother died, he dropped out of LSU and went to the Louisiana State Normal College (later the Northwestern State College) at Natchitoches. In September 1910, the ruggedly handsome young man started work as the teacher-principal of a school in Athens, near Shreveport. He was a dedicated outdoorsman on his days off and spent so much time hunting and fishing that his skin became weathered and cracked from the elements. In China later, his pilots nicknamed him “Old Leatherface.”

The young man became fascinated with aviation when he saw a Curtiss biplane at the Louisiana State Fair in Shreveport. Meanwhile, Chennault fell in love with Nellie Thompson, a buxom, pretty, high school valedictorian. They were married on Christmas Day and began to start a family. They would have six sons and a daughter.

When America entered World War I in April 1917, the young father resettled his family in Gilbert and went off to the Officers Training Camp at Fort Benjamin Harrison, an infantry school, in Indiana. Applying himself diligently to training and tactics, he was commissioned a first lieutenant in the Infantry Reserve in November 1917. But he failed to get overseas duty.

Instead, a new career opened up that would change his life when he was transferred to the Army Signal Corps Aviation Section. He earned his wings in April 1919, but his only flying assignment was a stint on the Mexican border. When his tour ended in 1920, he was routinely discharged and returned home to Gilbert. He planted a field of cotton, but he was restless. Aviation had taken hold of him. “I have tasted of the air,” he told his father in a letter, “and I cannot get it out of my craw.”

An Early Critic of the Early Air Corps

Chennault took a Regular Army commission later in 1920 and resumed his flying career. But his star did not rise. A prickly individualist with a sharp mind, he was an outspoken critic of outdated Air Corps doctrine.

He was stationed at a number of airfields for several years, including three years (1923-1926) as commander of the 19th Pursuit Squadron based at Ford Island in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. It was a pleasant billet for Chennault and his family, and, while proving himself to be a first-class pilot and squadron leader, he found time to begin a deep and detailed study of pursuit tactics. He bristled regularly at the belief of Air Corps “bomber generals” that planes like the new Martin B-10 bomber—a fast aerial pillbox—made fighters obsolete. Chennault remained an insistent, vocal proponent of the pursuit plane.

In his view, the perceived ineffectiveness of fighters in combat stemmed not from inherent limitations, but from pursuit tactics devised over the Western Front in 1914-1918. “There was too much of an air of medieval jousting in the dogfights,” he wrote, “and not enough of the calculated massing of overwhelming force so necessary in the cold, cruel business of war.” He believed that combat aviators, like infantrymen, won engagements by fighting as teams.

Clinging tenaciously to his belief at a time when the Army Air Corps was still teaching dogfighting tactics, Chennault was promoted to captain in 1929 and graduated from the Air Corps Tactical School at Langley Field, Virginia, in 1931. Remaining there as an instructor, he published in 1935 an influential and much-used textbook, The Role of Defensive Pursuit, in which he emphasized the role of the fighter plane in aerial superiority. He also advocated, in an era before the advent of radar, a defensive warning system based on a network of trained spotters.

Meanwhile, to demonstrate that a group of planes could operate effectively as a tightly knit team in combat, Chennault led two other Air Corps fliers—Lieutenant Haywood “Possum” Hansell and Sergeant John “Luke” Williamson—in forming a precision flying team known as the “Three Men on a Flying Trapeze.” The so-called Army Air Corps Exhibition Group performed breathtaking aerobatics in formation—loops, spins, and turns—from 1932 to 1936.

But the Air Corps hierarchy was unmoved. Its Tactical School at Maxwell Field, Alabama, where Chennault, now a major, was instructing, stopped teaching fighter tactics in 1936. The following year, the 47-year-old Chennault left the service with partial deafness and chronic bronchitis. He was physically exhausted and unpopular, with his gruff manner diluting the impact of his innovative ideas. He retired with the rank of lieutenant colonel, and many of his superiors were glad to see him go.

Building Up the Chinese Air Force

The hidebound Army Air Corps was not ready to embrace such visionaries as Chennault and General William “Billy” Mitchell before him. But the Chinese, then threatened by the aggressive Japanese, had heard of Chennault and his expertise with pursuit tactics and asked him to advise their government. He went to China in May 1937 and met Madame Chiang Kai-shek, the wife of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, who was also a lieutenant colonel in the Chinese Air Force. Assigned to upgrade the tottering air arm, she gave Chennault the forbidding task of training and organizing air defenses. The two hit it off from the start. The craggy American colonel was captivated by the charming, shrewd Madame Chiang, and he wrote in his diary on the day they met, “She will always be a princess to me.” In the troubled years ahead, she was Chennault’s patron and steadfast champion.

At that time, the Chinese Air Force was in a pitiable state, with 500 aircraft on the books but only 91 serviceable. Within weeks of Chennault’s arrival, the Sino-Japanese War broke out, and he found himself overseeing a motley collection of Chinese pilots and international mercenaries that was outclassed by the Japanese Air Force. Chinese fliers who were supposedly combat ready left their airfields strewn with the wreckage of cracked-up planes. By October 1937, the Chinese had only a handful of Curtiss Hawk IIIs left.

Without delay, the energetic and resourceful Chennault set about transforming the Air Force into an effective fighting unit. He revised the training system, taught new tactics, and established a wide-ranging radio and telephone warning network.

Chennault’s tireless efforts paid off, and in the ensuing months his pilots began to put up a spirited defense against the ruthless Japanese raiders then bombing and strafing Chinese cities. But the Chinese fliers were no match for the superior numbers and higher performance of the enemy planes. The deadly Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero fighter was introduced to combat, and by the summer of 1940, the key city of Chungking was being bombed by 100 Japanese planes a day. The situation was hopeless, so the Chiangs decided to try to secure aircraft and pilots from America.

Recruits from the USA

Early in 1941, Chennault was back in his neutral homeland, aided by chubby, bespectacled T.V. Soong, Madame Chiang’s brother, minister of foreign affairs, head of the Bank of China, and China’s chief lobbyist in the United States. Soong gained President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s reluctant permission for Chennault to hire American pilots and mechanics for the Chinese Air Force. Madame Chiang, meanwhile, provided Chennault with $8,900,000 under a private corporation—named China Defense Supplies and chartered by the state of Delaware—to purchase the necessary hardware.

Through export representative William D. Pawley of Curtiss-Wright Aircraft Corp., Chennault was assured delivery of the fighter planes he needed. These were 100 single-engine, single-seat P-40 Tomahawks earmarked for the Royal Air Force but rejected as obsolete. Colonel Chennault discussed with Navy Secretary Frank Knox, Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr., and presidential adviser Thomas Corcoran the formation of an American Volunteer Group in China, and on April 15, 1941, Roosevelt signed an unpublicized executive order authorizing the recruitment of reserve military personnel for it.

Recruiting got under way immediately at Army and Navy bases, and volunteers came forward from fleet aircraft carriers and Army Air Corps pursuit and bombardment groups. About half of the men recruited were Navy or Marine Corps pilots, about a third came from the Air Corps, and the rest were commercial or test pilots. “Here’s an opportunity for real experience, combat experience,” said an AVG recruiter in 1941. “And, besides, there’s good dough in it.” The recruits signed one-year contracts, with the pay ranging from $250 to $750 a month, plus travel expenses, free quarters, and valet-interpreters. In addition, the Chinese government promised a $500 bonus for each Japanese plane shot down.

By mid-May 1941, the crated Tomahawks began to find their way to Rangoon harbor, and on July 7, the first contingent of AVG personnel—110 pilots, 150 mechanics, and a few support men—sailed from San Francisco. Because of neutrality laws, they carried bogus passports and posed as bankers, actors, clergymen, and even circus performers. By way of Singapore, they reached Toungoo, a primitive former RAF airstrip, on July 28. The AVG’s intended base at Kunming was not ready. The fighters were assembled at the Mingaladon airfield near Rangoon and were tested between August and December.

The Tomahawk Tactics of the Tigers

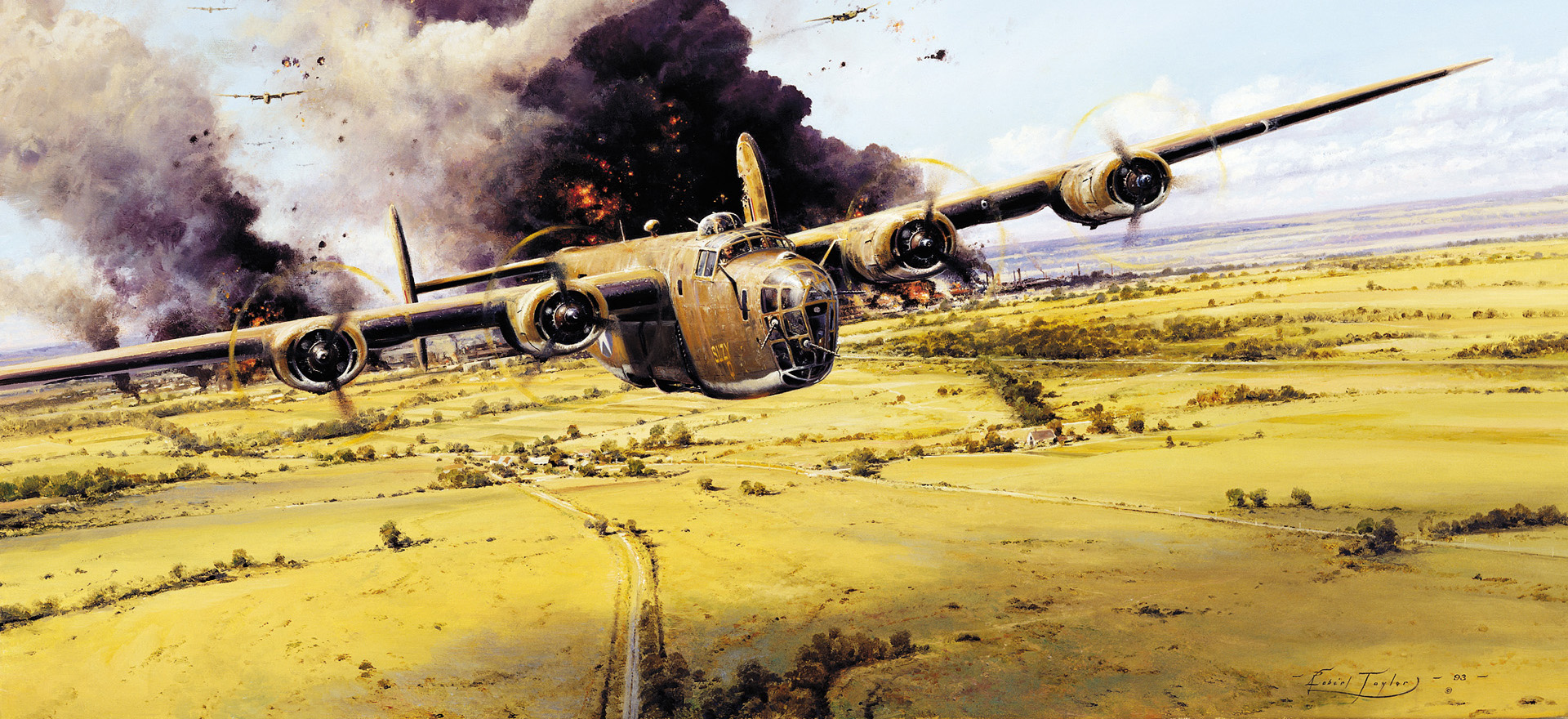

Chennault arrived on August 22 to find his recruits living in grass huts and suffering from suffocating heat, bad food, and fierce mosquitoes. He wasted no time in teaching the theories of fighter combat, showing the volunteers how to exploit the Tomahawk and deny the Japanese superiority in climbing and maneuverability. The P-40 was a heavy, durable plane with thick armor to protect the pilot. It was relatively fast in straightaway flight and could achieve great speed in a dive, but its weight made it sluggish in climbing and clumsy to maneuver by comparison with the lighter, more agile enemy fighters.

Defensive tactics were geared to the Hawks’ strengths and weaknesses. The pilots were advised to fly in pairs and never to engage the enemy Zero fighters or Nakajima “Kate” torpedo bombers in single duels. Chennault told his men, “Never, never, in a P-40, try to outmaneuver and perform acrobatics with a Jap Kate or Zero. Such tactics, take it from me, are strictly non-habit-forming.”

The main reason for the Flying Tigers’ later success lay in the unorthodox hit-and-run tactics laid down by Chennault. “Use your speed and diving power to make a pass, shoot, and break away,” he told his men. He emphasized his points by drawing diagrams of tactics on a chalkboard like a football coach, and he scrutinized the pilots’ aerial progress through binoculars while perched on a rickety bamboo tower. At least half of the pilots had never before seen a P-40, and the training was slow. Three men died in training accidents, and others gave up and went home. Torrential rains and mishaps kept the Tomahawks on the ground for long periods.

The Tigers Enter the Fight

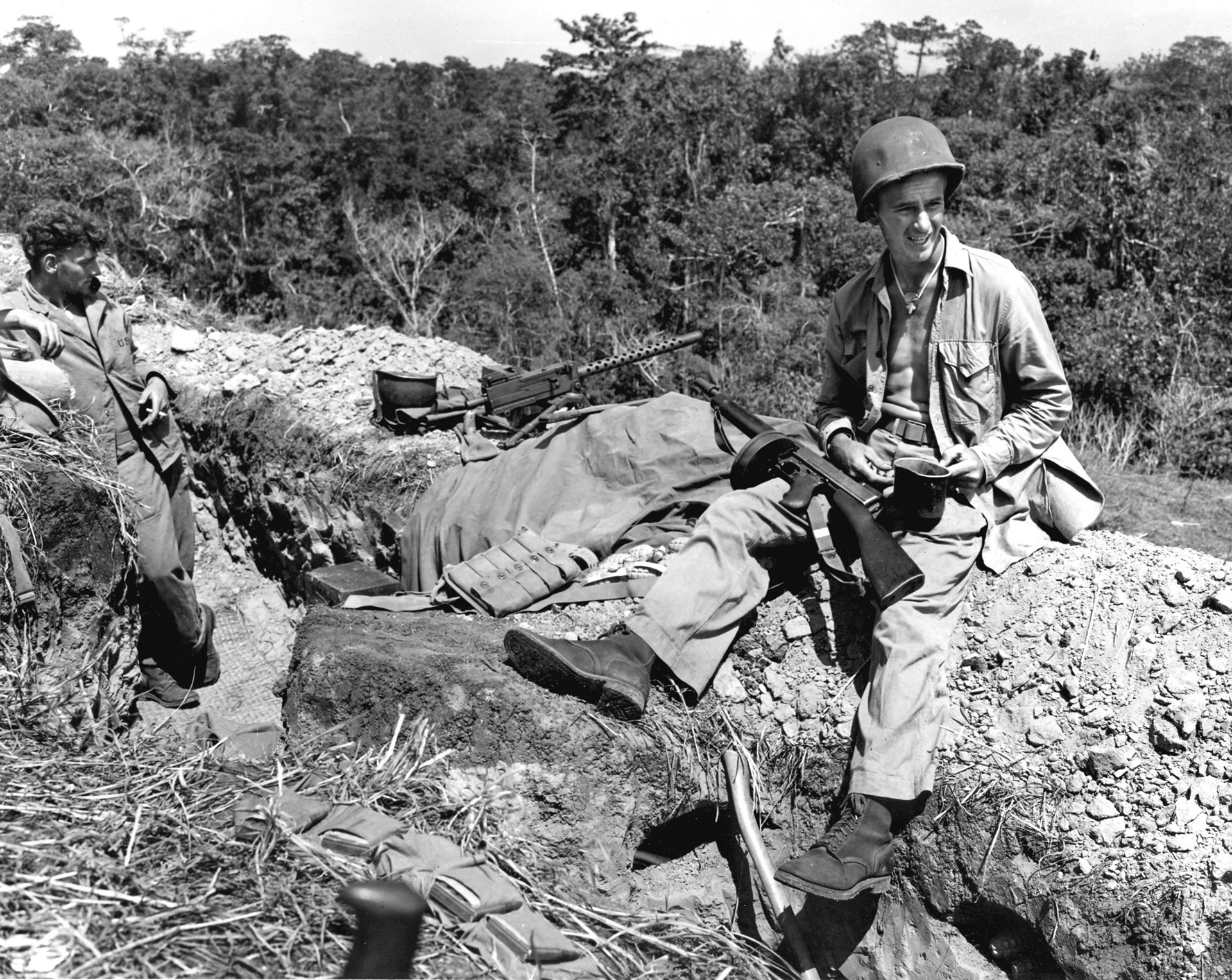

The Tigers were ready to commence operations at the time of the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor. Colonel Chennault split his forces between Burma, where one group supported the hard-pressed British defenders of Rangoon, and Kunming, where the other group set up a protective air screen for western China. From the outset, it was a makeshift operation waged by a ragtag outfit. The Tigers used chewing gum to plug bullet holes in their planes’ fuel tanks and patched riddled fuselages with adhesive tape. Because their Tomahawks had no bomb racks, the pilots experimented with incendiaries made of gasoline-filled whiskey bottles.

Yet, for all of their improvised operations, the fliers of Chennault’s “Scalper Squadrons” caused such havoc with Japanese formations over Burma that Tokyo radio announced, “The American pilots in Chinese planes are unprincipled bandits. Unless they cease their unorthodox tactics, they will be treated as guerrillas (meaning they would be executed if captured).” The AVG never numbered more than 200 aircraft, but Chennault’s training and guidance made it highly successful in combat.

Going into action outnumbered against enemy formations, and sometimes flying up to eight sorties a day, the Flying Tigers sought to deceive their foes as well as outshoot them. They would alter their voices over the radio and give orders to imaginary squadrons to create the impression of superior force. On February 25, 1942, the Japanese sent 166 planes to bomb and strafe Rangoon. Nine P-40s swooped on them, bagged 24 aircraft, and lost three. On the next day, about 200 enemy planes raided the city. Six Tomahawks downed 18 Japanese aircraft without loss. After the fall of Rangoon on March 7, 1942, Colonel Chennault withdrew his last few fighters from Burma to China. There, they defended the cities of western China and made raids over Burma, primarily to protect Allied supply convoys toiling along the winding, tortuous Burma Road.

A Resourceful Unit

Because war matériel entering China amounted to a trickle, Chennault faced awesome logistical problems. Spare parts and other supplies had to be hauled thousands of miles by sea, rail, and air. “It was as though,” he said, “an air force based in Kansas was supplied from San Francisco to bomb targets from Maine to Florida.” After he established forward bases in China from which to attack enemy lines of communication, his supplies had to be transported 400 to 700 miles from Kunming by trucks and donkey carts that traveled over makeshift roads.

The AVG was less than a spit-and-polish outfit. Military formalities were dispensed with, and discipline was lax. All that mattered was destroying as many Japanese aircraft as possible. The pilots often wore high-heeled cowboy boots, caroused with native girls in smoky Rangoon bars, composed bawdy ballads, and donned full uniforms only for funerals and formal celebrations.

They painted fearsome, toothy sharks on the noses of their P-40s, a design calculated to have a psychological effect on the Japanese and one that was borrowed from No. 112 Squadron of the Royal Air Force based in Egypt. A Walt Disney Studios artist designed an insignia for the Tigers’ tailplanes—a winged Bengal tiger leaping through a V-for-victory symbol. Thus, Chennault’s fliers became widely known as the Flying Tigers.

Twenty-six aces emerged from the AVG ranks, and two later earned the Medal of Honor. These were former Navy pilot James Howard, who later distinguished himself in the European Theater, and Major Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, who shot down six Japanese planes while with the AVG and later led the famous Marine Corps “Black Sheep” Squadron in the Solomon Islands campaign.

The gallant service of the Tigers was noted in a special order of the day by Air Vice Marshal Donald F. Stevenson, the RAF commander in Burma. He stated, “The high courage, skillful fighting, and offensive spirit displayed mark the AVG as a first-class fighting force.” Later, in August 1943, Great Britain awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross to three AVG pilots— Charlie Bond, Tex Hill, and Ed Rector—for their services in the defense of Burma.

Much of the Tigers’ success depended on their resourceful ground crews, who minimized the enemy’s numerical advantage by keeping the patched-up, bullet-riddled P-40s operational. They labored in sub-zero temperatures on the Kunming Plateau and in 115-degree heat in the Burma lowlands. The mechanics, armorers, propeller specialists, radio technicians, and parachute riggers toiled for long hours, and they operated with precision. They often made repairs during enemy air raids. Spare parts were in such short supply that the ground crews had to scavenge in jungles and rice paddies to find what they could where planes had crashed. They used ingenuity to improve the performance of the Tomahawks, even rubbing wax on the fuselages to increase speed by as much as 10 miles an hour. The mechanics’ efforts were readily acknowledged by the pilots, one of whom told a war correspondent, “Save some big words for our ground crews. They have gone through strafings, dodged bombs, and have always been out there working on our planes at all hours.”

The AVG fought until July 4, 1942, when it was disbanded and formed into a regular Army Air Forces unit called the China Air Task Force, with Chennault in command. The Flying Tigers’ operations were absorbed by the 23rd Fighter Squadron.

Chennault Stays in the Skies Over China

Chennault, meanwhile, had returned to U.S. service as a colonel in April 1942. After ranking as a brigadier general in the Chinese service, he was promoted to the same grade in the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF). He organized the China Air Task Force to carry on the air war against the Japanese. Prodigious feats were performed by his transport plane crews in ferrying supplies 500 miles from Assam, India, over the forbidding Himalayas—the Hump—to Kunming. Violent storms and high winds made every trip a nightmare, and monsoon downpours reduced visibility to zero.

In March 1943, Chennault was promoted to major general and given command of the Fourteenth Air Force, which, from bases in southern China, fought a war of attrition and tactical support for Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell’s Chinese and U.S. ground forces.

Chennault’s tactical leadership was masterful, though he continued to be plagued with logistics limitations. Besides feuding with the acerbic “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell, he complained loudly about the lack of support he was getting. He resorted to dealing directly with Chiang Kai-shek and President Roosevelt, and this earned him the distrust of General George C. Marshall, Army chief of staff, and General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, commander of the USAAF. Chennault remained in command of the Fourteenth Air Force until August 1945, and retired from the service the following October.

Chennault After the War

Critical of the failure of U.S. authorities to support the Nationalist Chinese government against the Communist threat, Chennault rejoined Chiang Kai-shek in 1946 to organize the Chinese National Relief and Rehabilitation Air Transport Service. He served as its president and also headed other aviation organizations in Formosa (later Taiwan) until 1950. He returned to his homeland in January 1958 and died of lung cancer in New Orleans on July 27 that year. One of his last bedside visitors was Madame Chiang Kai-shek.

Chennault was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Nine days before his death, the U.S. Air Force bestowed upon him the honorary grade of lieutenant general. An Air Force base at Lake Charles, Louisiana, was named for him, and a bust was erected at a park in Taipei, the capital of Taiwan. Chennault was the only Westerner so honored in the Republic of China. He was posthumously inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in Dayton, Ohio, in 1972, and a 40-cent postage stamp was issued in September 1990 to memorialize Old Leatherface.

The exploits of the Flying Tigers were related by one of their members, Captain Robert L. Scott, winner of the Silver Star, in his books, God Is My Co-Pilot, Flying Tiger, and The Day I Owned the Sky, and in two motion pictures, God Is My Co-Pilot (1945), starring Dennis Morgan, Dane Clark, and Raymond Massey, and Flying Tigers (1942), with John Wayne, John Carroll, Paul Kelly, and Anna Lee.

Nakijima “Kate” Torpedo bombers or Nakajima “Oscar” (Ki-43) fighter planes?