By Sam McGowan

In the annals of World War II, one of the most famous airplanes is the British-developed Supermarine Spitfire, an agile, elliptical-wing fighter that has become synonymous with the Royal Air Force victory in the Battle of Britain. Thanks in large measure to news reports coming out of that battle, the Spitfire captured the imagination of a generation of English and American schoolboys, some of whom would themselves be flying Spitfires by the war’s end half a decade later.

Until the introduction of the North American P-51 Mustang, the Spitfire was considered to be the most maneuverable of the Allied fighters, and it was favored by nearly everyone who flew it.

R.J. Mitchell’s Flying Machine

The Spitfire was a product of the Supermarine Company, a British firm that started out building flying boats before World War I. In 1916, the firm was joined by a young engineer named R.J. Mitchell, who would eventually design the Spitfire. After World War I, Supermarine was heavily involved in designing and building flying boats for competition. Mitchell, however, envisioned smaller, sleeker designs that would be capable of much higher speeds than were possible with the ungainly flying boats.

After the 1923 Schneider Trophy Race, Mitchell decided to design a high-performance seaplane for the 1925 event. Unfortunately, the first Mitchell design crashed during the race, which was won by Lieutenant James H. Doolittle of the U.S. Army. Ironically, 17 years later Doolittle would have command of several Spitfire squadrons operating in North Africa. Supermarine’s S.5 finally took the Schneider Trophy in 1927, establishing the company’s reputation as a builder of fast airplanes and Mitchell’s as their designer. The following year the company was purchased by Vickers. When the worldwide depression of the 1930s led England to decide not to promote an entrant for the 1931 race, Lady Houston, a wealthy Englishwoman and patriot, funded the entry. Thanks to her generous gift, Britain captured the Schneider Cup and took it home for good.

Until that time, Supermarine’s efforts had been aimed at seaplanes, but Mitchell convinced the company to design and build an entry for an Air Ministry specification for a day-night fighter. Although Supermarine had been purchased by Vickers, the original company was given the latitude to design airplanes under its own name. Supermarine named its new fighter “Spitfire,” but the gull-wing airplane was not a success.

One of the main reasons for the first Spitfire’s failure was the long landing distances required by the high-speed design; the Air Ministry had specified that the new fighter would have to operate from short fields. Meanwhile, Rolls- Royce had developed a new engine it called the Merlin, and Mitchell decided to adopt it for a military fighter for the RAF. In 1934, the Air Ministry put out a specification for an eight-gun fighter, and Mitchell took up the challenge; the company adopted “Spitfire” as the name of its design.

To arm the new fighters, the Air Ministry worked out an arrangement with the American Browning Arms Company to build its .30-caliber machine gun in the UK under license and to convert it to the British standard .303 cartridge. The prototype Spitfire took to the air on March 5, 1936.

Spitfires Fight the Phony War

In the mid-1930s Britain had begun rearming, prompted at least in part by the rise to power of Adolf Hitler in Germany. When the Air Ministry put out a requirement for an eight-gun production fighter, Mitchell undertook to redesign the Spitfire to meet the new specifications. After he learned that he was terminally ill, Mitchell devoted himself to the project, working night and day and perhaps speeding up his own demise. Unfortunately, the designer succumbed to cancer before the first production airplane had been completed. But the new fighter he had designed would live on to earn Mitchell his place in military aviation history.

The first Spitfires entered operational service in mid-1938; RAF 19 Squadron at Duxford was the first to receive the new fighter, with the first airplanes delivered on August 4. The second Spitfire squadron was also at Duxford; RAF 66 Squadron began replacing its Gloucester Gauntlets with Spitfires on October 13. Other squadrons began receiving the new fighter the following year. By August 1938 the RAF had 400 operational Spitfires, with orders for 2,100 more. Barely a year later, England would be at war, and the Spitfire would be one of the country’s most important weapons.

Tragically, the first aircraft shot down by Spitfires were friendly Hawker Hurricanes. Shortly after Britain declared war on Germany during the first week of September 1939, a false alarm led to the scrambling of RAF fighters against a nonexistent enemy. Two Spitfires from 74 Squadron came up behind a pair of Hurricanes from 56 Squadron and shot both airplanes down; both pilots were killed by the friendly fire. A court-martial resulted in an acquittal on the basis that the real fault lay with the fighter controllers who had directed the action. Another Spitfire was lost the same day when the pilot allowed his airplane to stall at low altitude; it spun into the trees before he could recover.

On October 16 a Spitfire pilot was credited with the first official kill of the war for RAF Fighter Command. German reconnaissance aircraft operating over the Firth of Forth led to the scrambling of Spitfires from Scottish bases. A three-plane section from 603 Squadron intercepted a twin-engine aircraft and shot it down. But such engagements were rare during the period known as “The Phoney War,” when contact with the enemy was rare. The RAF Auxiliary squadrons took advantage of the temporary lull in the conflict to bring their pilots up to operational readiness in their Hurricanes and Spitfires.

Spits over France

When the Germans invaded France and the Low Countries on May 10, 1940, the Spitfire squadrons were held in reserve while six squadrons of Hurricanes were sent into action over France with the British Expeditionary Force. The decision was logical, in that the difficulties of forward operations could be better endured with only one type of fighter. The Hurricane was better suited for operations from primitive airfields owing to its wide landing gear track—and there were a lot more of them.

As the situation on the Continent worsened, the Spitfire pilots of 19 Squadron were told that they would be deploying to France. Before they could make the move, Prime Minister Winston Churchill decided to suspend further reinforcement of the fighters in spite of French pleas for additional fighter support. His decision to hold the remainder of the RAF in reserve is credited with saving the fighter force and, ultimately, keeping England in the war. As it was, few of the Hurricanes that went to France returned to English soil.

Contrary to the belief among BEF troops who awaited evacuation from Dunkirk that Fighter Command had turned its back on them, RAF fighters—including Spitfires—were heavily engaged against the Luftwaffe during the evacuation. It was just that most of the action took place far away from the beach and out of sight of the frightened British soldiers awaiting evacuation—or capture.

Previously, action by Spitfires had mostly been against German intruders over England. The first dogfight took place on May 23, when Spitfires from 74 Squadron encountered German fighters over France. The squadron commander had to make a forced landing at Calais. A rescue effort was mounted with a Miles Master escorted by two Spitfires flown by Flight Lieutenant Deere and Pilot Officer Allen. A flight of Me-109s appeared over the field just as the Master took off. The pilot, Flight Lieutenant Leathart, returned and landed. Deere, who would become one of the RAF’s most famous pilots, shot down one of the Messerschmitts almost immediately. The Spitfires kept the Me-109s away from the field, and the Master took off and returned to England.

The action over Calais was the first engagement between Spitfires and Me-109s, but air action escalated when the BEF was pushed into an enclave at Dunkirk. Even though the troops on the ground were not aware of it, a great air battle was taking place over France as the British Royal Navy attempted to evacuate the BEF from France. The RAF lost 229 aircraft during the evacuation, of which 70 to 80 were Spitfires.

The Spitfire’s Rise to Fame: The Battle of Britain

The summer of 1940 saw what came to be known as the Battle of Britain, and it was during this time that the Spitfire became famous and RAF fighter pilots became heroes. Adolf Hitler was determined to force the British government to capitulate, and Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, chief of the Luftwaffe, convinced him that his airmen could accomplish the task. Hitler’s plans were not to invade and occupy England, but to force the British into an alliance with him against the Soviet Union, a country rich with natural resources, which was his real objective. The Luftwaffe built up a massive force of bombers and fighters in the Low Countries and in the north of France in preparation for the campaign, which commenced in early August.

The only thing standing in the way of Hitler’s plan was the RAF Fighter Command, specifically its Hurricane and Spitfire squadrons. Fighter Command apparently recognized that the Spitfire was the better suited of the two to dogfighting and established tactics under which Hurricanes would be vectored against bombers and the Spitfires against fighters. The RAF fighter pilots, those who flew Hurricanes and Spitfires alike, were on constant alert throughout the weeks of the intense German attacks, often standing by in their cockpits where they awaited the call to scramble.

Once a squadron became airborne, it immediately fell under the direction of the RAF ground controllers, many of them young women, who vectored them into position for an attack. There was a controversy over tactics between the two senior fighter commanders, as 12 Group Commander Air Vice Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory preferred the “big wing” concept of assembling his fighters in strength. The problem was that assembling the formations took time—time during which the German bomber formations penetrated deeper into British airspace and were often able to drop their bombs before they could be intercepted.

Air Vice Marshal Keith Park commanded 11 Group, and it was in his area that most of the attacks were taking place. He was often frustrated because 12 Group was not quick to respond when called on to contribute fighters to the battle. In spite of the command problems, RAF Fighter Command managed to prevail, inflicting heavy losses against the Luftwaffe bombers, until they finally reached the point that Germany could no longer endure them. The German bomber commanders elected to discontinue daylight attacks against English targets and turned to night raids. Credit for the British victory was shared by the Hurricane and Spitfire pilots.

Spitfires go on the Offensive

With the turn to night attacks by the Germans, the Spitfire’s role as an interceptor had pretty much ceased. Attempts were made to use Spitfires to intercept German bombers at night, but most efforts were futile. The night-fighter role was eventually filled by twin-engine aircraft with two crewmen, one of whom was trained to operate equipment that was designed to detect the ignitions of aircraft engines. The development of radar increased the effectiveness of the specially adapted night fighters, and Spitfires were used primarily in daylight operations.

In late December, barely two months after the Battle of Britain, the RAF began changing from a defensive to an offensive posture as Fighter Command launched attacks against German airfields in France. On December 20, a pair of 66 Squadron Spitfires took off from Biggin Hill and headed across the English Channel on a low-level strafing mission over the Le Touquet airfield. The two fighters shot up the Luftwaffe base, then returned home without opposition. Two weeks later, five squadrons made a sweep up the French coast, with some sorties going 30 miles inland. From then on fighter “rhubarbs” would be a regular occurrence. Early 1941 also saw the introduction of the Spitfire to night fighting, but the need for them in the night-fighter role decreased with the appearance of Bristol Beaufighters a few weeks later.

American Volunteers

Two decades before, during World War I, scores of young Americans had volunteered to fly for France and formed the Lafayette Escadrille, formed in memory of the young French nobleman who came to America to fight with the Continental Army during the American Revolution. When war again broke out in Europe, many young Americans sought to revive the Escadrille, but the quick defeat of the French military forces prevented it.

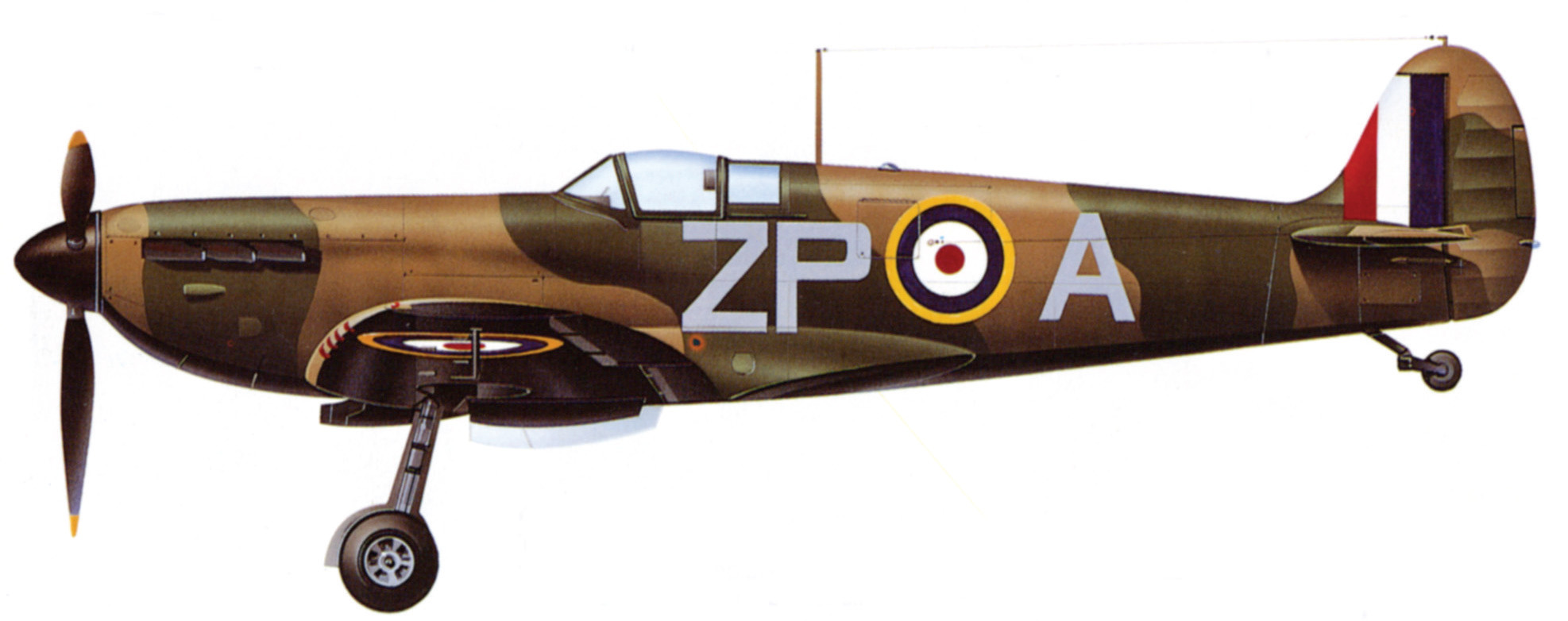

Britain was still in the war and the volunteers switched their allegiance. Dispatches from England by American war correspondents during the Battle of Britain also influenced many Americans to consider volunteering to fight for Britain. The RAF began accepting applications from American pilots and in October 1940 formed the “Eagle Squadron” made up entirely of pilots from the United States. After forming at Church Fenton on October 19, 1940, the Eagle Squadron was initially equipped with Hurricanes. Nine months later it switched to Spitfires. A second Eagle Squadron was formed on May 14, 1941. It, too, was initially equipped with Hurricanes, but soon switched to Spitfires as well. A third squadron was formed on August 1, 1941.

Spitfires in the Eighth Air Force

On December 7, 1941, the United States officially entered World War II, although American military personnel had been involved in the war on a clandestine basis for more than a year. In early 1942, General Carl Spaatz, the chief of the Army Air Corps Combat Command, decided to establish an air force for operations from the UK. In June, the first American air units embarked for England to join the new U.S. Eighth Air Force. One of the units was the 31st Pursuit Group, which had previously flown Bell P-39 Airacobras. Because of the lower cost of the Spitfire and the need for P-39s in the Pacific, Spaatz decided to send the group overseas by ship without airplanes and to equip them with Spitfires after their arrival. The United States contracted under the Lend-Lease program for 600 Spitfires to be delivered by the end of 1943. The American 52nd Fighter Group also received British Spitfires.

In the autumn of 1942, Eighth Air Force Spitfire strength increased when the three Eagle squadrons transferred to the U.S. Army Air Corps, where they made up the newly organized 4th Fighter Group, and were consolidated at Debden. With the transfer of the Eagle Squadrons, the United States had three fighter groups equipped with Spitfires. While the 31st and 52nd Fighter Groups moved to North Africa, the 4th remained in England, where its three squadrons constituted the only operational American fighter squadrons in the British Isles until early 1943.

As an already proven combat aircraft, the Spitfire was thought to be a good choice to introduce U.S. Army fighter pilots to combat in Europe. But the Allied role was changing from defensive to offensive operations, and the Spitfire came up lacking for the new kind of war. The Spitfire was designed to be a short-range interceptor, and it lacked the range necessary to escort the heavy bombers of the Eighth Air Force on long-range missions into western Europe. External fuel tanks increased the range of the Spitfire, but not enough to accompany the bombers into Germany.

The only American-built fighters in England in 1942 were Lockheed P-38 Lightnings, and they were being held in reserve to reinforce the newly established Twelfth Air Force in North Africa. Consequently, the 4th Fighter Group Spitfires were the only game in town. Ironically, the 4th Fighter Group continued to operate under RAF Fighter Command for a time, while RAF Spitfires served as the primary escort fighters for VIII Bomber Command throughout 1942. Spitfires would continue to serve with American fighter squadrons well into 1943, when they were replaced by American aircraft, particularly the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt.

High Casualties Over Dieppe

In August 1942, one of the fiercest air actions of the war occurred as Spitfires played the major fighter role in support of the Canadian commando raid on the French port at Dieppe, code-named Operation Jubilee. More than 2,300 sorties were flown that day, with large numbers of them flown by Spitfires. Spitfires from 129 Squadron fired the first shots of the action as they struck shore installations during the dark hours before sunrise at 4:45 am. The 129 Squadron Spits were followed by other Spitfires escorting light bombers on missions against the shore batteries near the landing beach.

Inexplicably, the Luftwaffe failed to appear over the beaches until midday. When they did come, the German attack was met by four squadrons of Spitfires that had been dispatched by Air Marshal Leigh-Mallory, who was keeping close watch on developments in France. Four other Spitfire squadrons escorted a flight of American Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers attacking the airfield at Abbeville. Unfortunately, the troops on the beaches met stiff resistance that inflicted heavy losses. Almost 4,000 commandos were killed, wounded, or captured, including some 3,000 Canadians. Air casualties were not light—106 RAF aircraft were reported lost, 88 of which were Spitfires.

The War in the Mediterranean

As the attacks on occupied Europe and Germany increased in 1943, the drawbacks of the Spitfires became readily apparent. While Spitfires could escort cross-Channel missions into France and the Low Countries, they lacked the range to go deeper. As longer range American fighters arrived in England and entered operational service, the Spitfires turned more toward supporting short-range medium bombers on attacks against German airfields and other installations in France and attacking ground targets.

Spitfires served in every theater of the war where British and British Commonwealth forces fought. One of the first—and perhaps most important—overseas deployments of Spitfires was to Malta, where German and Italian bombers were attempting to pound the occupying British forces into submission. Air attacks commenced on Malta immediately after Italy entered the war on June 10, 1940, and continued for two years.

By March 7, 1942, when 15 Spitfires flew onto the island from the aircraft carrier HMS Eagle, the island had been under constant air attack for 20 months. The newly arrived Spits were rendered ineffective by Axis air attacks within a few days, and preparations were made for additional airplanes to be delivered by the carrier USS Wasp. On April 20, an additional 47 Spitfires reached the island, but their arrival had not gone unnoticed. Within two hours, German and Italian aircraft were hitting the island; by the end of the following day, only 18 Spitfires remained operational.

A third reinforcement was more successful, as the pilots took off from the carrier in planes that were armed and ready to fight. Sixty-four Spitfires were launched from Eagle and Wasp, and most arrived safely on May 9. Additional fighters arrived a little over a week later. With the arrival of the additional Spitfires, the defenders of Malta were able to mount a more effective air defense, and Hitler decided to forgo his plans to invade the island.

Spitfires flown by both British and American pilots played a major role in the Allied effort in North Africa. The threat of damage from swirling sand initially kept the Spitfires out of the Middle East, but the development of improved air filters reduced the problem. British Spitfires first served in Egypt, then joined the Desert Air Force in North Africa. The American 31st and 52nd Fighter Groups picked up Spitfires at Gibraltar, then flew them on to French North Africa, where they engaged in a brief combat with Vichy French fighters upon their arrival. American- and British-flown Spitfires played a major role in the defeat of the Luftwaffe in North Africa.

Late War Roles of the Spitfire

With the attention of the Allied forces directed toward the Mediterranean, the fighter effort from the UK was focused on defending against continuing German air attacks, on rhubarbs against German airfields and shore installations in France, and on escorting American bombers on cross-Channel missions into France and the Low Countries. As the Allied emphasis changed to preparing for the invasion of Normandy, Spitfires were converted into ground-attack aircraft with the addition of hard points for bombs and rockets. Ground attack would continue to be a major Spitfire mission through the remainder of the war. Another role for the Spitfires was intercepting the pilotless V-1 buzz bombs before they could reach their targets in the vicinity of London.

Spitfires also played a role in the Far East, where the first of the type arrived in India in October 1942. Within two weeks they were flying missions over Burma. Spitfires would play an ever-increasing role in the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater and were instrumental in preventing the Japanese from overrunning Allied installations at Imphal in the spring of 1944. Spitfires also saw service in the defense of northern Australia, although it was not until early 1943 that they entered operations there. Several Australian and New Zealand squadrons in the UK had previously been equipped with the Supermarine fighter. As pressure on the Northern Territories lessened, Royal Australian Air Force 79, 452, and 457 Squadrons moved northward to New Guinea.

Developing the Seafire

The success of the Spitfire led to an adaptation of the type for the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy, following a precedent that had already been set by the Hawker Hurricane. To distinguish them from the RAF aircraft, the Navy fighters were referred to as Seafires. Although later production models featured folding wings to allow storage aboard carriers, the first Seafires were nothing but production Spitfires that had been modified for carrier landings by the addition of an arrester hook.

RAF and U.S. Spitfires had been flown off carriers during deliveries to Malta and North Africa, but the Seafires had true carrier capability. Unfortunately, the narrow landing gear and elongated nose made carrier landings difficult, and the Seafire was not a successful adaptation. Seafires did serve in the Pacific aboard the carrier HMS Implacable, but other British carriers in that theater carried American aircraft types.

Service Around the World

Spitfires served with many nations, not only in the international squadrons of the Royal Air Force that included Czechs, Poles, Belgians, Norwegians, and South Africans. They were also exported. The Soviet Air Force operated more than 1,300 Spitfires as both fighters and reconnaissance aircraft. Turkey was an early customer for the Spitfire, while Portugal received about 50 of the planes in late 1943. Spitfires were also provided to the Egyptian Air Force. A failed British and American diplomatic effort toward Sweden would have diverted 200 Spitfires to the Swedish Air Force in return for a suspension of shipments of Swedish ball bearings to Germany. After deliberating for several days, Sweden rejected the offer.

Whether it was as the hero of the Battle of Britain, interceptor and attack aircraft in North Africa, defender of Malta, or early escort fighter for strategic bombers, the Spitfire earned its rightful place in military aviation history.

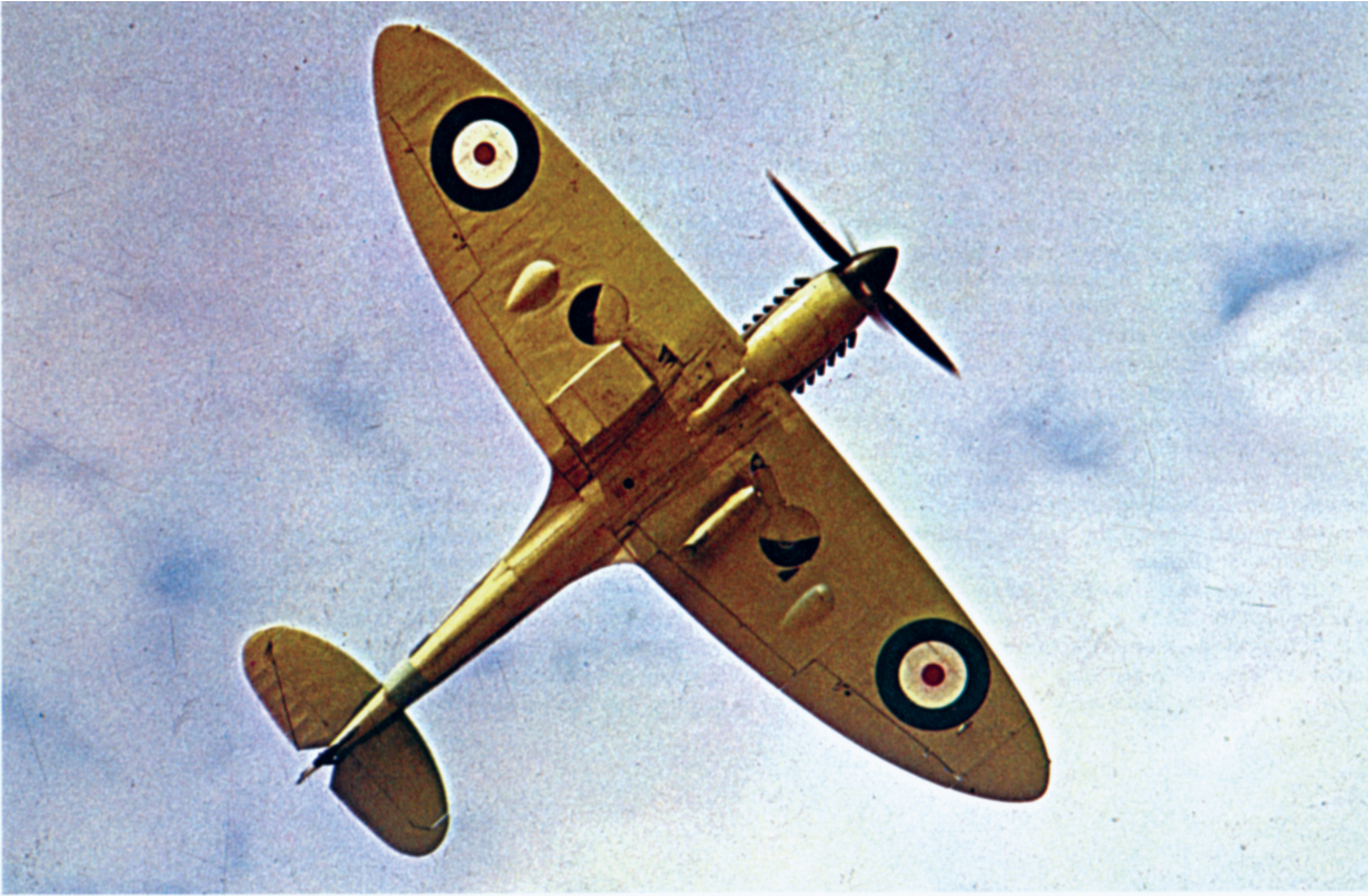

The colourised photo of a Spitfire avoiding an attacking Me109 is a German propaganda photo. This Spitfire had already been captured by them and German black and white crosses were applied to the wings and fuselage together with their code letters G+X when they evaluated it. The crosses were eventually painted out and fictitious “RAF roundels” applied. That is why the roundels are the wrong type for the fuselage and on the wings they are painted too close to the cockpit. Another black and white photo exists of this Spitfire “attacking” a Dornier 17, again another German propaganda photo.

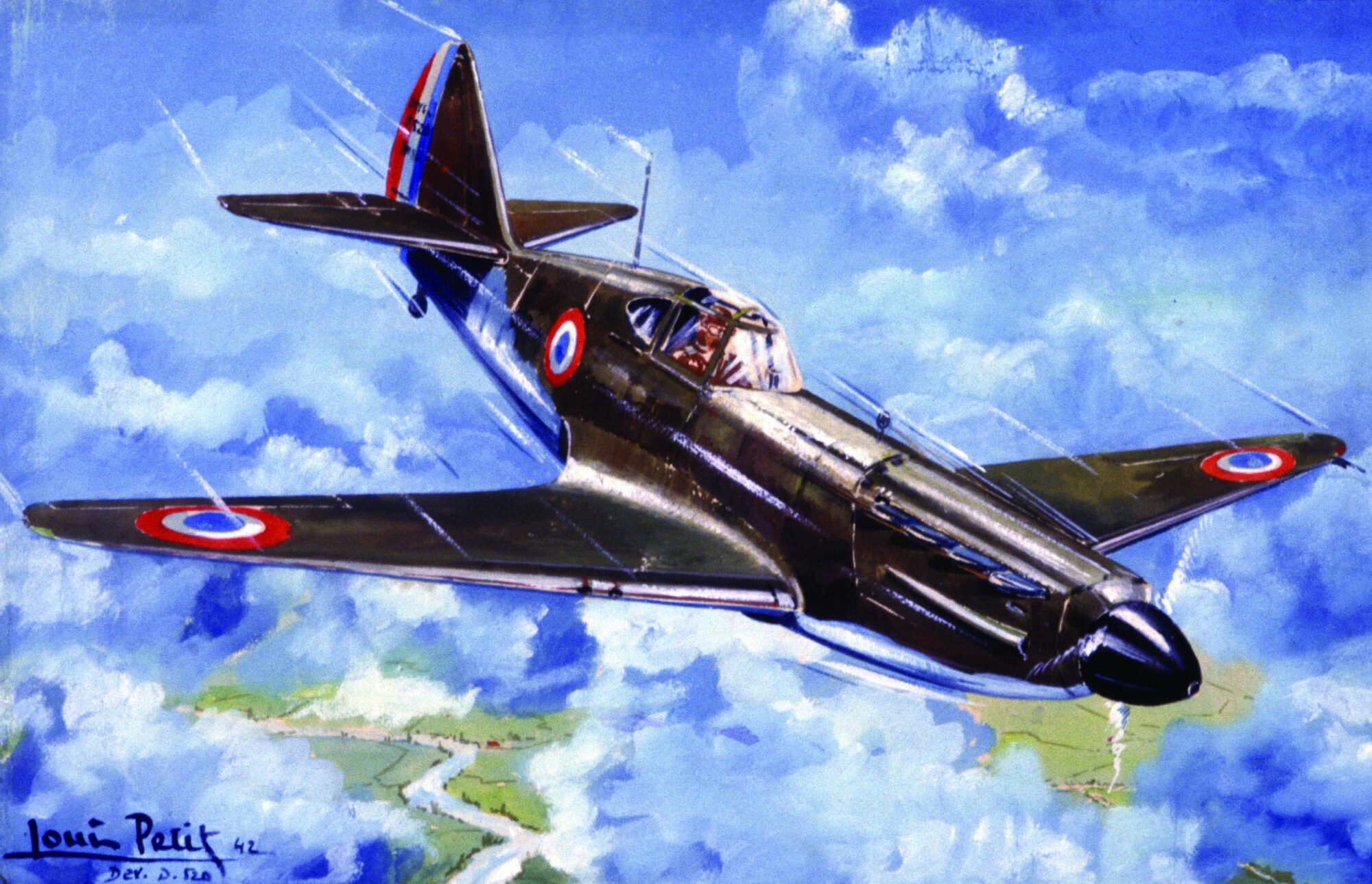

Never mind that. The cover picture is a French Dewoitine 520, not a Spitfire!