By Victor Kamenir

In August 1943, immediately after the Battle of Kursk, the Red Army launched a series of follow up operations, resulting in the liberation of a large swath of Nazi-occupied Soviet territory. However, by the end of September, the Soviet offensive ground to a halt against the great Ukrainian river Dnieper.

This major river was the centerpiece of the Panther-Wotan Line, or Eastern Wall, a grandiose German scheme to halt the Red Army. Adolf Hitler, in his directive on August 11, 1943, ordered the creation of the Panther-Wotan Line as the last bulwark stopping the Soviet onslaught. He was echoed by Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi minister of propaganda, who wrote in his diary on September 24: “We must try under all circumstances to hold the Dnieper line; in case we lose it, I wouldn’t know where we might gain a new foothold.”

The Panther section was the portion of the envisioned German line running north roughly from the area of Smolensk to the Baltic Sea. The Wotan portion, the larger segment, extended south from Smolensk to the Black Sea. Even though the Wehrmacht did not have the time, resources, or manpower to turn this into the impregnable wall envisioned by Hitler, it was a formidable natural obstacle, with the high western bank of the Dnieper River overlooking the other side.

Situated on the west bank of the Dnieper was the Ukrainian capital of Kiev, a major highway and railroad nexus. Rapid capture of this strategic objective would allow Soviet forces several options for further operations. The offensive in a northwesterly direction would threaten to cut the German front in two and drive a wedge between the German Army Groups Center and South. The advance southwest would position the Red Army at the Hungarian and Romanian borders. Turning south along the Dnieper River would threaten to cut off and destroy the bulk of the German forces in the Ukraine.

Two Soviet army groups, known as fronts, were advancing in the direction of Kiev. The Central Front, under General Konstantin K. Rokossovski, would brush north of Kiev with its extreme left flank. However, the bulk of operations against Kiev would be conducted by the Voronezh Front under General Nikolai F. Vatutin. The two fronts were renamed the 1st Belorussian and 1st Ukrainian, respectively, on September 20.

Race to the River

The Soviet offensive began on September 9, 1943, with the objective of reaching the Dnieper River by October 5. Unexpectedly, after securing Hitler’s permission, the commander of Army Group South, Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, gave orders on September 15 to retreat to the western side of the river.

As the German forces rapidly pulled back, the dash to Dnieper became a race as both Soviet and German units attempted to reach the river first, with combatants often moving along parallel routes. Even falling back rapidly, the Germans fought a series of sharp rearguard actions. Still, the leading elements of the 1st Ukrainian Front began approaching the river in the afternoon of September 21, ahead of schedule.

The jubilant but exhausted Red Army suffered heavy casualties during its summer offensive. Supply lines were overstretched, and many units were in dire need of refit and replacements. Skilled bridging units were lagging behind. Fuel was in such short supply that General Konstantin Malygin, commanding the IX Mechanized Corps in the Third Guards Tank Army, gave orders to take fuel from all nonessential vehicles, even artillery, to ensure that tanks and vehicles carrying motorized infantry had enough fuel to make the last jump to the Dnieper. Marshal Georgi Zhukov, representative of the Supreme Command overseeing operations of the 1st Ukrainian Front, wrote in his memoirs: “There was no opportunity for detailed preparation for the advance to the Dnieper. The forces … were extremely fatigued by constant fighting.”

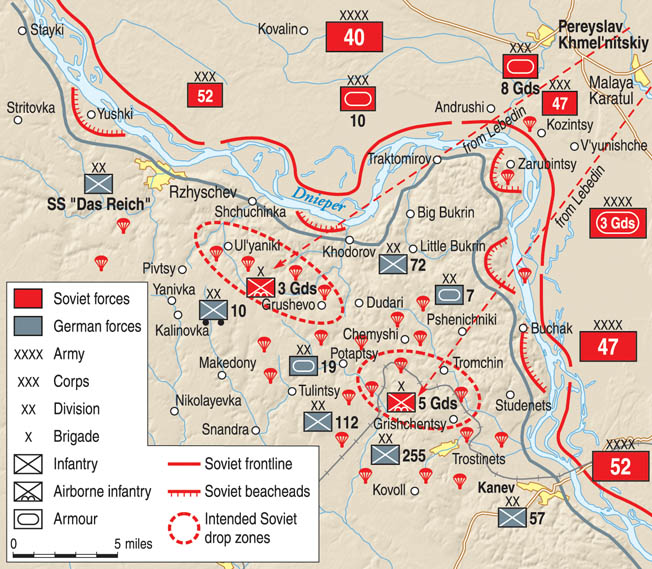

The leading units of Soviet Fortieth Army and Third Guards Tank Army of the 1st Ukrainian Front approached the river in the area of the so-called Bukrin Bend, roughly 180 miles south of Kiev. This east-facing bend in the river, named after two villages, the Big Bukrin and the Little Bukrin, was one of the few areas allowing the Soviet artillery to dominate the opposing bank. However, the rugged terrain within the Bukrin Bend, intersected by a multitude of deep ravines, prohibited maneuvers by mechanized units and greatly impeded all others. Still, the Soviet command concentrated one of its major efforts at this location because the terrain on the eastern bank allowed them to stage large forces unobserved by the Germans.

Attempting to capitalize on their momentum, small units of Red Army soldiers began crossing to the western bank almost as soon as they arrived. Due to the availability of only a few boats, some of the first assault parties were as small as five or six men. The next morning, September 22, the soldiers located a sunken ferry. It was raised and quickly patched up, and platoon-sized groups began moving across. German forces in the area were no more than a few scattered pickets, and a battalion of Soviet motorized infantry was able to occupy the village of Zarubentsy, at the tip of the bend, practically without firing a shot.

However, the Germans reacted quickly to this development, and the 19th Panzer Division was rushed south from Kiev. At the same time, the German XXIV Panzer Corps was retreating in good order to the east side of the river in the vicinity of Kanev, south of Bukrin Bend. Its leading division, the 34th Infantry, also hurried to the Soviet beachhead. By the end of the day, they began probing Red Army positions around Zarubentsy.

A Plan to Support the Beachhead

The fighting began in earnest on the morning of September 23. The two German divisions were greatly aided by difficult terrain and Soviet logistical challenges. The lack of sufficient river craft slowed Soviet buildup on the beachhead, while the Germans rushed forward elements from the XXIV and XLVII Panzer Corps. By September 26, nine German divisions bottled up and stalemated the Soviet forces in the Bukrin Bend, preventing them from breaking out.

Chief of Red Army General Staff, Marshal S.M. Shtemenko, wrote in retrospect: “It wouldn’t have been superfluous to plan an additional crossing of the Dnieper in the vicinity of Kiev in case of a setback of the offensive from Bukrin beachhead. However, neither the General Staff, nor Front command, unfortunately, prepared this in advance.”

In mid-September, as the forces of the Voronezh Front were still hundreds of miles from the Dnieper, the Soviet Supreme Command ordered an airborne operation prepared in support of the ground forces. Three elite Guards airborne brigades, the 1st, 3rd, and 5th, from the Supreme Command reserve and totaling some 10,000 men, were grouped into a provisional corps under Major General Ivan Zatevakhin. A small number of staff officers was seconded from the Directorate of Airborne Troops to form Zatevakhin’s command element.

Commander of the Voronezh Front, General Nikolai F. Vatutin, was given the operational control of the airborne corps. His political deputy was none other than the future Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. Planning for this operation was shrouded in utmost secrecy, with Marshal Zhukov, who was present at the headquarters of the Voronezh Front, signing off on the finished product on September 19.

The plan was extremely ambitious, given the level of equipment, supplies, and capabilities of units tasked with carrying it out. Still, it was very thorough, with the smallest detail meticulously worked out. General Vatutin’s task for the airborne corps was to drop during the night of September 23-24 and establish a defensive perimeter immediately west of the Bukrin Bend to prevent German reinforcements from reaching the beachhead.

Planning the Operation

Aerial reconnaissance was to locate German forces in the area of the drop zones. Immediately prior to the commencement of operations, the Second Air Army supporting the 1st Ukrainian Front was to attack and suppress ground targets. Immediately after the drop, the front air forces were to switch to close support of paratroopers on the ground. Teams of liaison officers with their own radios and dedicated and redundant radio frequencies were established to ensure cooperation among the paratroopers, supporting aviation, and artillery assets. The landing itself would be conducted during two nights, with the 1st and the 5th Guards Airborne Brigades dropping first, followed by the 3rd Brigade the next night. The first two brigades were to be dropped at night 15 miles west of the Dnieper River and establish a defensive perimeter roughly 10 miles long by 15 miles deep.

The Long-Range Aviation Command provided the bulk of the 180 aircraft required to transport men and equipment. They were mainly Lisunov Li-2 planes, a licensed copy of the American Douglas DC-3 plane, as well as 35 gliders. The aircraft would fly from a complex of five airfields near Lebedin, 110 to 140 miles from the proposed drop zones. To facilitate navigation and approaches to the target area, the aircraft were to utilize radio beacons that were already installed at the airfields. The reciprocal beacons were to be set up in the drop zones by the first elements of paratroopers to land.

To further assist navigation to the drop zones, upon landing, the designated paratroopers were to fire off prearranged sequences of multicolored flares and set up bonfires on the ground in certain configurations. In all, 500 sorties were to transport the two airborne brigades on the first night of operations. The heaviest weapons available to paratroopers, 45mm antitank guns, were to be delivered on the second night, with planes landing on rough runways laid out by men already on the ground. Paratroopers were to be on their own for two to three days until they linked up with ground forces.

Soviet Airborne Infantry

The severe attrition of the first two years of war, with paratroopers often having to fight as regular infantry, whittled down the ranks of trained airborne soldiers. While the officer and NCO cadres of the three brigades contained some veterans of previous airborne operations, the majority of the rank and file had fewer than four practice jumps under their belts. Many of these men had never jumped from an aircraft before, having done their practice jumps from aerostats. Additionally, most of the men in the three airborne brigades were not volunteers and had been arbitrarily assigned to airborne units. Among thousands of men in each airborne brigade were also several dozen women, mainly doctors, nurses, and some radio operators. They jumped into combat alongside the men and shared all the dangers with them.

Discipline was strict. Any soldier found in dereliction of duty, conduct unbecoming, or refusing to jump was quickly shipped off to a penal battalion. A veteran of the 3rd Guards Airborne Brigade, Matvey Likhterman, at that time a radio operator in the antitank battalion, remembered that the majority of men in his battalion were aged between 18 and 22. Many years after the war, an interview with Likhterman was published on a Russian-language website. His reminiscences, as well as the memoirs of another participant, Grigoriy Chukhrai, were invaluable in describing the human aspect of the events that unfolded.

The combat kit of paratroopers was heavy, sometimes adding more than 80 pounds, plus their PD-42 parachutes. Likhterman remembered being armed with a carbine, 200 rounds of ammunition, six grenades, a knife, and a packet with American C-rations: “We did not have any incendiary grenades, riser cutters, entrenching tools…. We, the common paratroopers, did not have pistols or explosive charges, flashlights, flare guns.”

He ruefully remembered instructions to bury the parachutes once on the ground, which would be difficult to do since they did not have entrenching tools. Likhterman was part of the two-man crew of a radio station. Incredibly, carrying the spare batteries and code book, he was assigned to one aircraft, while his partner, carrying the radio, was assigned to another. As a radioman, Likhterman was instructed in case of imminent capture to destroy his codebook and then commit suicide, since he had to memorize the call signs and frequencies used by the brigade.

Amendments and Delays

Traveling by train and caught in endless delays, the three airborne brigades arrived late to their staging areas. The planes earmarked to carry the paratroopers were slow in gathering as well. Large numbers of trains and convoys carrying precious aircraft fuel did not arrive on time, further limiting the number of sorties to be flown during the crucial first day of the operation. Bad weather with ground-hugging fog limited the effectiveness of aerial reconnaissance, and the immediate vicinity of the drop zones was not scrutinized.

General Vatutin and his staff spent most of the day of September 24 amending the plan, also delaying the operation by a day, to the night of September 25-26, to allow more men and resources to arrive. The 1st Guards Airborne Brigade, under Colonel I.P. Krasovskiy, hopelessly late, was replaced by the 3rd Brigade to be dropped during the first night. The drop zones were adjusted as well. The 3rd Guards Airborne Brigade under Colonel P.A. Goncharov was to land in the area southeast of the town of Rzhischev, while the 5th Guards Airborne Brigade, under Colonel P.M. Sidorchuk, was to drop northwest of the town of Kanev.

Brigade commanders received the amended orders on the morning of September 25, the day of the drop. As each command echelon passed down orders and instructions, each subsequent command level had less and less time to brief subordinates. Company commanders had 15 minutes before planes took off to brief platoon leaders, who, in turn, had to brief their soldiers while in flight.

“And Then it Began!”

At 6:30 pm on September 25, the planes carrying the leading elements of the 3rd Airborne Brigade took off from their airfields at 10-minute intervals. As the aircraft crossed to the west side of the Dnieper River, they encountered an unforeseen problem. The rain, which lasted most of the day, stopped around the time the operation started, but left behind a heavy haze, reducing visibility to less than three miles.

The first few aircraft carrying men of Likhterman’s unit arrived over their assigned drop zones and dropped their planeloads of paratroopers without interference from German antiaircraft artillery. However, as more and more white parachutes blossomed overhead, German positions came alive. As the first Soviet pathfinders on the ground began firing off their prearranged sequences of flares, the Germans quickly caught on and began firing off multicolored flares of their own. Their trick had the desired effect, confusing many Soviet pilots overhead and causing them to drop their paratroopers in the wrong places.

Likhterman remembers: “Three flares went up. A minute later the same three flares went up to our left, then to our right, and five minutes later the flares in the same color sequences went up all around us, and it was impossible to figure out who was sending them up and where the rally point was.”

Numerous German flak guns began firing, sending up a large volume of ordnance. Soviet pilots frantically maneuvered to gain altitude while continuing to drop their sticks of paratroopers. Instead of the planned 1,640 feet, many paratroopers were dropped from higher altitudes, further scattering the units. It took longer than planned to exit the aircraft as well, with so many green paratroopers making their first jump from a plane in combat conditions at night.

The slow-moving Soviet planes, caught in the beams of German search lights, were subjected to punishing flak. Likhterman and his few friends on the ground observed in horror.

“The drone of aircraft sounded overhead. And then it began!!! Hundreds of tracer bullets went up. It became light as day. The flak cannons coughed. A terrible tragedy unfolded over our heads. I don’t know where to find the words to describe what happened. We saw the whole nightmare. The incendiary tracers pierced the parachutes, which were made from [nylon and] would immediately burst in flames. Tens of burning torches immediately appeared in the sky. Our comrades were dying, burning up in the sky, without a chance to fight on the ground. We saw everything. Two shot-down ‘Douglases’ were falling, without having a chance to unload their paratroopers. The lads were dropping like stones from their planes without having a chance to open their parachutes. An Li-2 hit the ground 200 meters from us. We raced to the plane, but there were no survivors.… The whole area around us was covered in white smears of the parachutes. And bodies, bodies, bodies: killed, burnt, smashed paratroopers.”

Unknown to Likhterman, one of the planes he observed falling in flames carried the commander of the 3rd Guards Airborne Brigade, Colonel Goncharov, who perished along with his staff.

In one of the following planes was Lieutenant Grigoriy Chukhrai, who later became a famous Soviet movie director. He remembered: “The events of that night are still in front of my eyes. The closer our plane got to the front lines, the angrier the flak guns sounded, searchlights probed the sky, illumination flares were continuously being launched. We were unlucky: we were dropping right over the flak guns.… I was falling toward a gleaming stream of tracers, through the flames of burning parachutes of my comrades.”

On Top of the Enemy

As mistake compounded on tragedy, the majority of paratroopers became scattered over an area 15 by 40 miles, with less than 10 percent of them actually landing within the designated drop zones. Over half of the Soviet soldiers landed within 10 miles of their targets, while some unfortunates were blown off course over 40 miles to the south. Dozens landed in the Dnieper River, and many drowned entangled in their parachutes. Incredibly, more than 100 men landed on the east bank, in friendly territory, and some landed inside the Soviet beachhead on the west side of the river.

The train carrying the compass locator system, which was to be set up at the beginning of the final approaches of the transport planes over the river, did not arrive at its designated position until after the operation was canceled. Likewise, the first paratroopers on the ground, almost immediately fighting for their lives, did not have time or opportunity to set up beacons at the drop zones. Therefore, Soviet navigators only had the river itself as the reference mark for keeping track of flight time to their targets. Lacking a single common reference point, several aircraft approaching on different vectors from five different airfields arrived at the river at different locations.

Unknown to Soviet intelligence, on September 25, two German divisions, one panzer and one mechanized, were moving through the Soviet drop zones on their way to reinforce German units in the Bukrin Bend. Whole detachments of Soviet airborne soldiers found themselves landing right on top of German encampments, which were rapidly coming alive. The unfortunate airborne soldiers were decimated. Still, many brave souls fired their weapons and threw grenades on their way down to certain death.

Calling the Operation Off

Upon landing, Lieutenant Chukhrai hit the steep bank of a small ravine and tumbled down, wrapping himself in his parachute with his arms pinned to his sides. He temporarily lost consciousness, and when he came to he could hear “dogs barking and Germans’ guttural shouts” nearby. Twisting and turning, Chukhrai managed to reach his knife, cut himself loose, and scurry to shelter.

He recalled: “Two Germans appeared at the lip of the ravine. I saw them outlined against the sky. One of them fired a long burst at my parachute. Apparently, he thought that the paratrooper was still there. Only then they carefully began to approach the pile of my parachute and rucksack. As soon as they were sideways to me, I opened fire and cut both of them down. Then I took off running.”

The Soviet timetable was completely disrupted, and shuttling aircraft continued to drop paratroopers into the confusion. No longer needing to maintain radio silence, Soviet air crews radioed in reports of an operation gone terribly wrong, supplemented by their verbal accounts once back at their airfields. The discovery of enemy divisions already in the drop zones made the whole operation irrelevant, and the Soviet commanders cancelled the remainder.

By the time the operation was called off, just under 300 sorties had been flown instead of the 500 planned for the first night. Instead of two full brigades, slightly over 4,500 men were dropped. The 3rd Airborne Brigade was deployed in its entirety but without its 45mm guns. Roughly half the 5th Airborne Brigade was dropped before the mission was called off. Almost 600 soft containers with equipment, supplies, and ammunition were parachuted as well.

The Hunted by the Germans

In addition to frontline combat formations in transit through the area, several thousand German security troops were staged near the drop zones in preparation for an unrelated anti-partisan operation. Among these security troops was at least one battalion from the Turkestan Legion, formed by the Germans from Soviet Muslim POWs, natives of Central Asian republics. Several smaller detachments of local Ukrainian police were present as well. These security troops responded quickly and began sweeping the area for paratroopers.

Confused fighting raged on the ground as many Red Army men perished alone or in small groups and a number were captured. Still, the survivors fought on and began gathering in groups large enough to offer resistance. NCOs and junior officers took command of scattered units, while some commanders landed without any troops to lead. Colonel Sidorchuk, commander of the 5th Brigade, landed in the Kanev woods alone and did not find any of his men until daylight.

Paratroopers landing in the heavily wooded areas near Kanev and Cherkassy fared better than others, finding more cover and concealment. Their comrades who landed on the northern side of the drop zone near Rzhyschev found fewer defensible positions. Those soldiers who managed to reach their designated rally points often found no one to direct them further. As groups formed, they moved off in different directions without coordination.

It was absolutely vital for lightly armed paratroopers to find their air-dropped supply containers with equipment and ammunition. However, the Germans also actively hunted for them. In some instances, the Germans set up ambushes near discovered containers, inflicting heavy casualties on paratroopers attempting to retrieve them.

The next several days became a nightmare of running fights, as survivors attempted to organize. The Germans deployed spotter aircraft to attack larger groups of paratroopers from the air and to guide their ground forces.

Soviet partisans, though hard-pressed themselves, attempted to contact and bring in scattered paratroopers. Besides the physical danger, paratroopers were dropped without food. Many men, cautious about lighting fires or going into villages, gathered raw corn or dug up raw potatoes to dull their hunger pangs.

As the brutal sweep for paratroopers continued, many captured soldiers were executed immediately. Local villagers giving aid or shelter to paratroopers were killed as well. Paratroopers hiding in barns or houses were sometimes burned alive when the structures were torched. As groups of airborne soldiers maneuvered through the area, they often came across the mutilated bodies of their comrades. German authorities offered local residents monetary rewards for turning in paratroopers, and some Judases collected their pieces of silver.

“For Bravery”

Still, heroism was not in short supply, not only among soldiers but civilians as well. On the night of the drop, Captain Sapozhnikov wrapped the flag of his 5th Brigade around his body. While in the air on the way down, the captain was hit in the leg and shoulder. Several soldiers found the unconscious captain and hid him in a haystack. The next morning the soldiers were discovered by a 15-year-old villager, Anatoliy Ganenko. The brave teenager took the soldiers to his mother, Serafima Ganenko, and together they sheltered and aided the soldiers for several days. After the wounded captain regained some strength, the soldiers decided to attempt to break out and reach the Soviet lines.

To avoid risking the flag, they left it with the Ganenkos. When the victorious Red Army liberated the area two months later, the mother and son turned over the flag to authorities. In 1976, more than 30 years after the war, following a petition from the airborne soldiers, Serafima and Anatoliy Ganenko received medals “for bravery.”

Forming a Provisional Brigade

Paratroopers were not able to establish radio communications with their command elements back on the east bank of the river for several days. Aerial reconnaissance and partisans undoubtedly reported that there were still plenty of survivors, desperately fighting and out of touch with their headquarters. During the next week, three more groups of paratroopers with radios were dropped. Most sources reported that these men disappeared without checking in, doubtless victims of German sweeps. On September 27, the southern detachment of paratroopers finally established tenuous radio contact with 1st Ukrainian Front headquarters.

On the north side of the drop zone, Major Lev gathered almost 100 soldiers, including Lieutenant Chukhrai. After losing many men in running fights with the Germans, their detachment was soon found by partisans. Once they had a chance to catch their breath, Major Lev ordered Chukhrai and two soldiers to attempt to reach higher headquarters and receive orders. It is apparent that neither Major Lev’s detachment nor the partisan band had radio communications with the higher echelons.

After several difficult days of travel, Chukhrai and his companions managed to cross the front lines, navigate the river, and report in. Chukhrai’s two companions were sent back with orders for Major Lev, while the future film director was kept on the Soviet side to help identify paratrooper stragglers dribbling in. From these survivors Lieutenant Chukhrai eventually learned that Major Lev’s group had been wiped out.

As the days wore on, more and more paratroopers banded together. In the south, Colonel Sidorchuk, commander of the 5th Airborne Brigade, gathered almost 1,200 men in the Cherkassy woods, and roughly 1,000 more men were still alive around the northern drop zone. Overall, more than 40 groups were scattered in the drop zones, some of them as small as a dozen men, others larger than 200.

The majority of these groups were too large to hide and too small to defend themselves, and most of the men who survived the first few days around the northern drop zone eventually perished or were taken prisoner. Likhterman recalled how his group was destroyed. Initially, they attempted to fight to the river, hoping either to link up with other Soviet soldiers or to swim across. However, the German cordon was too tight and the beleaguered paratroopers bounced from one firefight to the next. Casualties mounted, and ammunition was dwindling. A dozen survivors were finally bottled up in a small ravine and taken prisoner. They were out of grenades and had only a few rounds of ammunition. After almost six harrowing months of imprisonment, Likhterman managed to escape and rejoin the advancing Red Army.

The few remaining officers, led by Colonel Sidorchuk, worked hard at reorganizing the survivors. By early October, his roughly 1,200 paratroopers were formed into a provisional brigade of three battalions, plus four specialist platoons—reconnaisance, communications, combat engineers, and antitank (recoilless rifle).

Once communications with the headquarters of the 1st Ukrainian Front became firmly established, Sidorchuk’s force started receiving combat missions. Often in conjunction with partisans, paratroopers attacked German infrastructure and small units, carried out ambushes and acts of sabotage, and conducted thorough reconnaissance. A rough landing strip was laid out in the woods, allowing planes from the Soviet side to land in the occupied territory, bringing in supplies and instructions and taking out small numbers of wounded.

Fighting in the Bukrin Bend stalemated during October. The Soviet Twenty-seventh and Fortieth Armies, plus the Third Guards Tank Army, were in firm control of the Bukrin Bend. However, they were unable to break through determined German defenses. After reevaluating the situation, Zhukov and Vatutin shifted the main axis of attack to beachheads closer to Kiev, especially the Lutezh beachhead just north of the city. In a feat of operational skill, the 3rd Guards Tank Army was secretly withdrawn from Bukrin Bend, transferred to the east side of the river, and shifted north to Lutezh.

The Liberation of Kiev

On November 3, Soviet ground forces launched a massive pincer offensive at Kiev, supported by Second Air Army. After hard fighting, the Ukrainian capital was liberated; and on the morning of November 6, Zhukov, Khrushchev, and Vatutin sent Stalin a congratulatory telegram, announcing liberation of the city.

Surviving paratroopers under Colonel Sidorchuk continued fighting in Bukrin Bend. During the night of November 13, in a coordinated attack with other Army units, they broke through German defenses and linked up with Soviet troops. In late November, still over 1,000 men strong, survivors of the 3rd and 5th Guards Airborne Brigades were returned to Moscow.

Even though the airborne operation did not unfold as planned, the presence of paratroopers in the German rear had a significant effect on the fighting in Bukrin Bend. Their operations pinned down significant German forces that otherwise would have been used against the Red Army forces in the beachhead. Three Red Army soldiers—Major A. Bluvshtein, Senior Lieutenant S. Petrosyan, and Private I. Kondratyev—were awarded their country’s highest combat decoration, Hero of the Soviet Union.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments