By Jefferson M. Grey

To his contemporaries, Harun al-Rashid, fifth caliph of the Abbasid dynasty, seemed the most fortunate of men. During his 23-year reign, Harun brought the caliphate to the apogee of its power, winning repeated military successes against the rival Christian Byzantine Empire. The state and its subjects prospered under his rule, and Harun’s private life was marked by domestic felicity and fertility—he fathered 11 sons and 14 daughters by at least six wives and various concubines.

In the longer perspective of history, however, Harun is a tragic figure. He tried to forestall a power struggle by dividing authority between his two eldest sons, Amin and Ma’mun, and by carefully delineating the relative precedence and powers that each would have after his death. Ma’mun was Harun’s eldest son by six months, but he was the offspring of a harem slave, the captured daughter of a defeated rebel. Ma’mun therefore possessed a lower status in the royal family than did his slightly younger brother Amin, who was the son of Zubaydah, Harun’s favorite wife and a well-born member of the ruling house. Amin was given precedence in Harun’s line of succession. He was officially named Harun’s heir in 791, when he was five years old.

The Mecca Protocols

As the two youths neared adulthood, Harun developed misgivings. Amin was handsome, strong, and courageous, but he displayed a self-indulgent frivolity and lack of seriousness. By contrast, Ma’mun was intelligent, scholarly, and steadier in character. Harun revised his succession plan, which was publicly announced in Mecca’s Great Mosque during the annual pilgrimage in January 803. The new plan provided for a finely balanced power-sharing arrangement. Amin would inherit the title of caliph, but his authority would be limited to the western half of the caliphate: Arabia, Egypt, Syria, and Iraq. Ma’mun was to have dominion over the eastern half of the caliphate, encompassing all of Persia as well as the rich but restless region of Khurasan, with its four great cities of Samarkand, Merv, Herat, and Balkh. Amin was enjoined from interfering with Ma’mun’s administration. In addition, Ma’mun was named as Amin’s successor, and Amin was forbidden to select another heir.

Amin and Ma’mun, then 16 and 17 years old respectively, swore loyalty to each other, and Harun required high-ranking civil officials, senior military commanders, well-known jurists, and tribal leaders to do the same. The original agreements, which have become known as the Mecca Protocols, were hung upon the interior walls of the sacred black shrine known as the Ka’aba to ensure that their terms would become widely known.

Fadl ibn al-Rabi, the Troublesome Vizier

Harun’s carefully constructed arrangements started to fall apart immediately after his death six years later. Although Harun had hoped the Mecca Protocols would ensure peace between his two eldest sons, some of his own top officials considered this virtual bifurcation of the empire to be unworkable and unwise. Foremost among these was Fadl ibn al-Rabi, Harun’s vizier, who was with the caliph when he died. Fadl moved quickly to bolster the more blue-blooded Amin’s position at Ma’mun’s expense.

During the first 20 months after Harun’s death, Fadl repeatedly pressed the malleable Amin to test his brother with various actions that transgressed the provisions of the Mecca Protocols. In the late summer of 810, Amin demanded that Ma’mun give up his position in Khurasan and return to Baghdad, ostensibly to assist in running the empire. Ma’mun understood that refusing Amin’s demand would mean civil war, but surrendering his authority and returning to Baghdad was no less dangerous. Hoping to buy additional time, Ma’mun responded with a conciliatory letter, contending that “my remaining here will be more profitable to the Commander of the Faithful and more useful to the Muslims.” Amin and Fadl brushed aside Ma’mun’s protestations. “Two bulls cannot be together in one camel herd,” Amin told an adviser who urged him to respect his father’s wishes.

That November, Amin decisively repudiated the Mecca Protocols, deposing Ma’mun from his position in Khurasan and the line of succession. As his new heir, Amin designated his young son Musa. Amin also ordered the original Mecca Protocols removed from the Ka’aba and destroyed. Amin and Fadl began organizing a great military expedition that they confidently expected would sweep up the highway from Baghdad to Khurasan, brush aside Ma’mun’s smaller provincial forces, and bring him back in shackles to Baghdad.

Ma’mun and Amin Assemble their Armies

As commander of his army, Amin selected an experienced but widely feared soldier named Ali ibn Isa ibn Mahan. Ali was originally from Khurasan, where his father had been an early and prominent member of the underground network that organized the Abbasid revolution that overthrew the Umayyad dynasty. Fadl and Amin expected that Ali’s appointment as commander of their expeditionary force would terrify the people of Khurasan. But the news that the cruel and greedy Ali would be returning instead fired many Khurasanis with a fierce determination to fight for their property and their lives.

To defend Khurasan against Ali’s army, Ma’mun called on Harthamah ibn al-A’yan, perhaps the most distinguished old soldier in the Abbasids’ service. Harthamah, an Arab from northern Afghanistan, first entered the military sometime in the 760s. During the next 40 years, he fought rebels in the swamps of the Egyptian delta and on the sands of the Tunisian deserts before assuming the governorship of Khurasan in 806. Where Ali was arrogant, unscrupulous, and self-serving, Harthamah was straightforward, principled, and selflessly loyal. But he was also old and so hobbled by arthritis that often he could not stand.

On March 7, 811, Amin summoned members of the Abbasid family and his principal officers to hear Fadl read a declaration of war against Ma’mun. One week later, Ali led 40,000 soldiers east from Baghdad up the highway toward the Zagros Mountains and the Iranian plateau on the first leg of their 1,100-mile march to Khurasan. Meanwhile, Harthamah awaited the arrival of troops he had called in from the frontier and recruited additional soldiers from among the rebels who had fought against Ali during his governorship. To gain additional time to complete his preparations, Harthamah dispatched a contingent of 3,800 troops under an officer named Tahir al-Husayn to establish an advance post at the walled city of Rayy, where the highway from Baghdad first entered Ma’mun’s territory.

Tahir was in his mid-thirties, an experienced professional soldier who had lost an eye in battle. He made a clear-headed assessment of his position. Given that he was outnumbered at least 10-to-1, the obvious course was to accept a siege inside Rayy, holding out within its walls for as long as possible. But Tahir feared that Rayy’s citizens, terrified by the size of Ali’s army and his harsh reputation, would betray him in hopes of saving their own lives and property. Rather than see his men trapped and hunted down in the streets of Rayy, Tahir led his troops out onto the open plain and established a position west of the city. When Ali arrived with his army, he established his camp on somewhat lower ground; several miles of sand flats and low hills separated the two sides.

Tahir’s Bold Advance

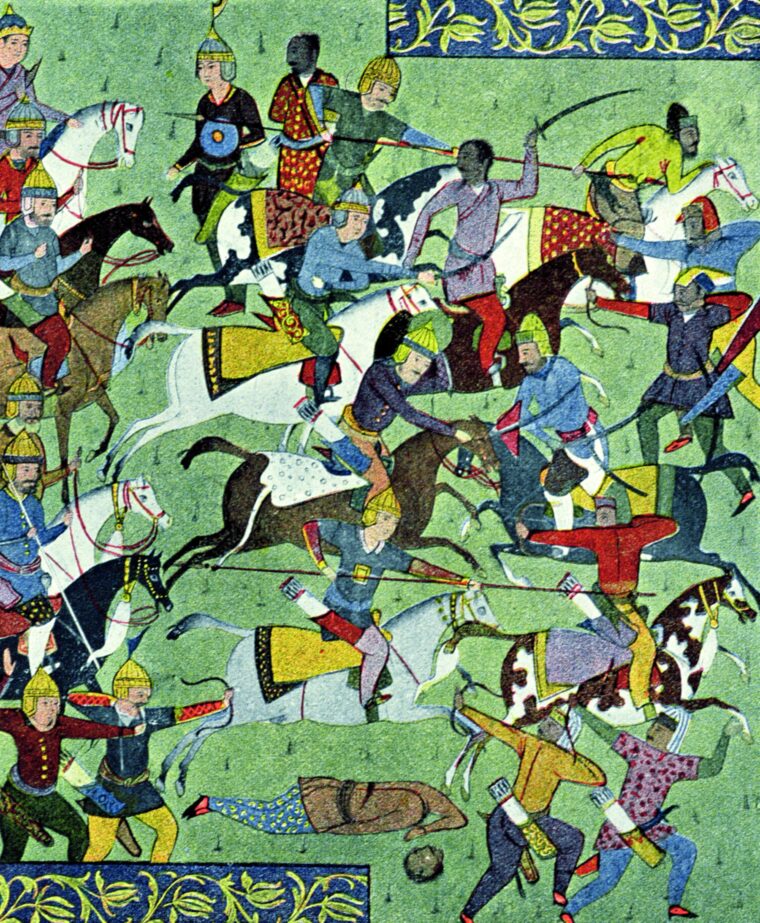

Supremely confident, Ali opened the battle with a crushing attack that drove in Tahir’s advance guards and pressed both wings back against the center. Tahir’s troops held, but another assault would finish off his force. Resolving that he and his men would take the battle to their enemies, Tahir led squadrons of Khwarazmian horsemen toward the center of Ali’s army. Seconds later, his cavalry crashed into Ali’s ranks, transforming the scene into a pandemonium of twisting horses, struggling men, and clouds of dust. In the confused melee that followed, Ali was knocked off his horse. Wounded and disoriented, he found himself surrounded by several of Tahir’s troops. One of them, a young page from Tahir’s bodyguard, closed in, cut Ali’s throat, and sliced off his head.

Tahir sent Ali’s head back to Ma’mun, along with a letter announcing his victory. But Tahir did not rest on his laurels. Rather than waiting for Ma’mun’s main army under Harthamah to arrive from Merv, Tahir marched 100 miles northwest to Qazvin, where he scattered a large garrison of Amin’s troops. With his rear secure, he next moved against Hamadan, defeating the new army recently dispatched from Baghdad. After Hamadan fell, Tahir and his army continued west and entered the Zagros Mountains, where he fought off a surprise attack by what was left of Amin’s army. When he reached the western side of the mountains near Hulwan, Tahir and his troops were only 150 miles from Baghdad.

Tahir was joined at Hulwan by Harthamah with Ma’mun’s main army of 30,000 men. But Ma’mun, his vizier, and Harthamah decided that lower Mesopotamia should be cleared of Amin’s forces before they marched on Baghdad. Tahir was dispatched to take the provincial capital of Ahwaz, 260 miles southeast of Hulwan in Khuzistan. During the first half of the year 812, Tahir’s army swept through Khuzistan and lower Mesopotamia. He smashed another of Amin’s armies outside Ahwaz, killing its commander and taking the city. After he occupied Ahwaz, Tahir turned west for the fortified city of Wasit on the Tigris. Wasit fell on March 20.

A House-t0-House Siege

After fighting his way through the maze of canals connecting the Tigris and Euphrates rivers south of Baghdad, Tahir reached the capital’s southern outskirts that May. In mid-August, Tahir got his army moving again, swinging around the west side of Baghdad. On August 25, he camped at the Anbar Gate, an archway northwest of the city that stood on the road leading to the town of Anbar. This move cut Amin’s sole remaining line of communication with the rest of his dominions and initiated the siege of Baghdad.

When the siege began, Baghdad was exactly 50 years old. It had been founded in 762 by Mansur, the second caliph of the Abbasid dynasty, who gave it the name Madinat as-Salam, or City of Peace. Mansur’s original foundation, the Round City, stood west of the Tigris, a giant pearl resting among branching canals that linked the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. The heavily fortified Round City was protected by a water moat, a raised berm, and three concentric sets of walls made of sun-dried bricks. The outer wall stood 60 feet tall, with circular bastions every 60 yards. The even more massive second wall was 90 feet in height and nearly 40 feet wide across the top. The caliph’s soldiers, officials, and servants occupied houses between the second wall and a third wall that marked off the innermost precinct of the Round City. The area inside the third wall was reserved for government offices and the palaces of the reigning caliph’s sons, with the mosque of Mansur and the Palace of the Golden Gate at the center.

In contrast with the massive defenses girdling the Round City, Baghdad’s remaining residential districts were completely unfortified. The siege did not involve assaults upon a fortified circuit wall but rather upon improvised barricades and fortifications linking house and garden walls that Amin’s troops and civilian supporters constructed around the city’s outer perimeter. The siege was characterized by street-by-street, and sometimes house-by-house, urban warfare of the most destructive kind.

Both sides made heavy use of artillery to shower stones and Greek fire down upon their opponents. As the bombardments devastated Baghdad’s neighborhoods, many of Amin’s regular troops, who were relatively well-off and had more to lose, became demoralized and listless. But the urban proletariat, described vividly as “street vendors, naked ones, people from the prisons, riffraff, rabble cutpurses, and people of the market,” showed unexpected spirit and developed into the backbone of the defense. These irregular troops, many of whom were of African origin, became known as the Naked Army because they went into battle without armor or other body protection. They improvised helmets and neck protectors from plaited palm leaves, and they made shields and reed mats that they covered with tar and stuffed with sand and gravel.

The Formidable Naked Army

The first battle of the Naked Army, an attempt to destroy a fire base that Harthamah had established on the eastern bank of the Tigris below the city, ended with a humiliating repulse. But as they gained fighting experience, the naked warriors proved themselves surprisingly formidable. This was epitomized by the battle of the Salih Palace, which took place in February 813, roughly six months into the siege. Ali Farahmard, Amin’s commander in the sector of the palaces of Princes Salih and Sulayman on the west bank of the Tigris just north of the Round City, wrote to Tahir offering to surrender the area if he and his officers were granted amnesty. Tahir readily agreed. On the night of February 12, 813, he sent a picked commando force of his best officers to take possession of the Salih palace.

The irregulars of the Naked Army launched a savage counterattack against the Salih palace and its grounds. The fighting ended with an astonishing triumph for Amin’s amateur soldiers. Tahir’s elite fighters were trapped inside the Salih palace and virtually annihilated. Shocked by the disastrous outcome of his attack on the Salih palace, Tahir ordered vast swaths of the city to be razed.

Amin’s irregular troops also proved their mettle in fighting on the east bank of the Tigris. Part of Harthamah’s forces under Ubaydallah ibn al-Waddah had occupied the quarter of al-Shammasiyah on the eastern side of the Tigris. Hatim ibn al-Saqr, who commanded Amin’s irregular troops in eastern Baghdad, launched a night attack that caught Ubaydallah by surprise and drove his forces out of al-Shammasiyah. Harthamah brought up additional troops to support Ubaydallah. In the confused night fighting, Harthamah himself was briefly captured by one of the naked warriors, but was not recognized. One of Harthamah’s troops soon liberated him, but not before word that he was missing in action had reached his main camp. The camp broke up in panic, and Harthamah’s troops fled back up the highway toward Hulwan.

Destroying Amin’s Court

Tahir was exasperated by his senior compatriot’s humiliating defeat. He threw another bridge of boats across the Tigris, crossed the river with his troops, and routed Amin’s men from al-Shammasiyah. Once the quarter fell, Tahir moved into position on the western bank of the Tigris just below the Khuld and Qarar palaces of Amin and his mother Zubaydah and started pounding them into ruin. As Tahir’s artillery began smashing down the roofs and walls of their homes, Amin, his children, and Zubaydah fled to the Palace of the Golden Gate inside the Round City. As he departed, Amin ordered the Khuld palace burned to deny its rich contents to looters. As flames from the caliph’s palaces rose into the night, Amin’s court all but dissolved. Soldiers, eunuchs, harem women, singers, and musicians scattered into the darkness.

The following day, Amin sent a letter to Tahir, offering to surrender and abdicate if he, his family members, and officials were guaranteed amnesty and safe conduct. When Tahir refused, insisting on unconditional surrender, Amin sought terms from Harthamah, who promised to send a boat to the western bank of the Tigris to take custody of Amin. Outraged, Tahir determined to frustrate Amin’s plans. Tahir believed that because he had done the lion’s share of the fighting, Amin was properly his prize. Tahir suspected that if Amin was taken to Khurasan, Ma’mun would show mercy to his half brother. Tahir considered it intolerable that Amin should live.

On the evening of September 25, Amin said a tender farewell to his two young sons, then mounted his favorite horse and rode to the river with a few of his officials. When he reached the quay, Harthamah was already waiting in a small bark. As Amin stepped aboard, Harthamah kissed Amin’s hands and greeted him fondly. The bark then pushed off into the current, heading for the torchlights on the eastern bank.

Tahir was watching from the riverbank. He had stationed several boats farther out in the river while keeping others hard by the bank until they saw Harthamah’s bark start to pull away. As soon as it did so, Tahir’s boats set off in pursuit, and a picked group of strong swimmers slipped quietly into the water and swam after the unsuspecting Harthamah and Amin. As Harthamah’s bark began to move toward the middle of the river, a swarm of skiffs suddenly emerged out of the darkness. Shooting arrows and hurling bricks, Tahir’s men closed on Harthamah’s craft. Swimmers came up underneath the bark and flipped it over, pitching Harthamah, his aides, and Amin into the Tigris.

Harthamah was fished out of the river by one of Tahir’s skiffs. Amin swam to the riverbank below the charred ruins of the Khuld palace, where he stumbled ashore wearing nothing but his trousers and was quickly captured by Tahir’s pages. The half-naked Amin was taken to a house near the Kufah Gate. Just before midnight, a group of heavily armored Khurasanis led by one of Tahir’s closest aides burst into the room with swords drawn. Amin defended himself desperately for a few moments with a pillow, but he was pitilessly cut down and decapitated. His remaining troops in the Round City surrendered the following morning. The War of the Two Brothers was over.

Fragmentation of the Caliphate

Ma’mun apparently had intended to spare his half brother, and his relations with Tahir thereafter were chilly. Rather than confirming Tahir as governor of Baghdad, Ma’mun instead dispatched him to govern the frontier districts of upper Mesopotamia and Syria. After spending seven years in semi-exile, Tahir at last was rewarded with a position that matched his talents and services: viceroy of Khurasan. He died less than two years after assuming his new post. Harthamah had an even less happy fate. In June 816, he was arrested, beaten, and thrown into prison, where he soon died.

Ma’mun ruled the caliphate until he died in 833 at the age of 46. He was an attractive figure: diligent, humane, intellectually curious, and a great sponsor of learning. But the War of the Two Brothers had fatally weakened the military class that comprised the principal support of the Abbasid dynasty, and neither Ma’mun nor his successors managed to create a satisfactory substitute. During the middle of the ninth century, the caliphs increasingly found themselves at the mercy of an expensive and dangerous praetorian guard of Turkish slave-soldiers who made and murdered caliphs as impulse dictated. The caliphate began to fragment, and warlords and provincial leaders paid little heed to the caliph’s wishes. By the end of the ninth century, the great empire that Harun al-Rashid had bequeathed to his two eldest sons was nothing more than a fading memory.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments