By John Mikolsevek

History is full of great men and great deeds. All American schoolchildren know the story of George Washington crossing the Delaware River in the dead of winter during the Revolutionary War. Yet how many are told of Washington’s less successful exploits in the French and Indian War? While George S. Patton was no George Washington, he nevertheless was one of the most controversial and popular commanders in American history. After World War II, children heard the saga of “Old Blood and Guts” and how he led the swift-moving Third Army across western Europe in pursuit of the crumbling Nazi Army. But Patton’s military achievements did not begin and end in World War II. Instead, they started in World War I. And without his experience in the Great War, Patton might never have learned the fine art of command, of how to combine soldiers and tanks into one irresistible, mighty phalanx—a skill that served the Allies well in the next war.

Patton Joins the World War

When the United States declared war on Germany and the Central Powers on April 6, 1917, Patton was serving on the staff of General John J. Pershing, his mentor and idol. As a soldier and commander, Pershing was everything the 31-year-old Patton wanted to be. Strong-jawed, muscular, and imposing, Pershing garnered respect just by walking into a room. A tough disciplinarian, he demanded the most from his staff and soldiers; his aides lived in fear of his wrath. Patton began to mimic Pershing in word and deed. Already known as a loud-mouthed martinet, Patton, during his time with Pershing, refined his ideas and beliefs on military protocol. Strict about discipline, he insisted on perfect military protocol. A formal salute became known derisively among the men as a “Georgie Patton.”

After accompanying Pershing on his punitive expedition against Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa in 1916, Patton joined the general’s personal staff, where he used his wife Beatrice’s vast fortune, his own political connections, and a growing relationship between his sister Nita and Pershing to cement his ties to the quick-rising general. After the United States declared war, Patton followed Pershing to Europe. Along with 60 other officers and 128 War Department clerks, civilians, and enlisted men,

Patton left New York City on May 28 aboard the British steamer HMS Baltic. During the voyage, Patton kept himself in shape, collected money for war orphans, and worked on his French. While participating in the Stockholm Olympics in 1912, where he finished fifth in the pentathlon, Patton had fallen in love with French culture and language, and although far from fluent in French, he became an instructor on the voyage over. Even Pershing frequented his lessons.

On June 8, Baltic docked at Liverpool to wild celebration, including the playing of “The Star Spangled Banner” by the Royal Welch Fusiliers. At last the Americans had arrived. After landing, Patton’s first assignment was to lead 67 troops to their quarters in the Tower of London. While not particularly thrilled with the assignment, Patton knew that almost every officer back home would trade jobs with him. Although still far from the front, he was closer to it in London than he would have been in Washington, D.C. For the next few days, Patton kept busy socializing, drinking, and fruitlessly ordering his troops around. After a week of celebrating, Pershing and his staff left for France. Arriving in Paris on June 13, Patton finally saw his first glimpse of the war, “several train loads of British wounded; they did not look very happy.” He believed that it was only a matter of time until he had his own crack at fighting.

Once again without specific duties, Patton functioned basically as the commander of the headquarters troops. The job entailed commanding guards on duty, making sure that there were enough chauffeurs for the automobiles and that the cars were running perfectly. Patton complained to his wife that “personally I have not a great deal to do. I would trade jobs with almost anyone for anything.” Freely utilizing his wife’s wealth, he purchased a 12-cylinder, five-passenger Packard automobile worth $4,386—the equivalent of more than $50,000 today—and endeavored to be seen everywhere. The fancy new car turned the heads of many superior officers, who sometimes wondered how a young captain could afford such a vehicle.

On July 20, Patton traveled with Pershing to meet with the British commander in chief, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig. Prior to departure, Patton installed a license plate on the front of their automobile that read, “U.S. No. 1.” During the meeting, Pershing impressed Haig, who nevertheless judged Pershing’s staff to be rather unspectacular. But Haig liked Patton, writing in his diary after the meeting that “the A.D.C. [aide-de-camp] is a fire-eater and longs for the fray.” For Patton, there could be no greater praise.

Gunning for the Tank Corps

Despite the praise from Haig, Patton’s disgust with his monotonous job continued to grow, as more of his West Point classmates were promoted ahead of him. Patton soon began to look for other jobs. By late July, for the first time, he had a serious conversation about tanks and their role in the war. Trained as a cavalryman and therefore appreciative of mobile warfare and aggressive tactics, Patton seemed less than enthusiastic about tanks, writing, “The tank is not worth a damn.” He stuck with his staff job, but after following Pershing’s move to Chaumont on September 1, he grew more frustrated, reporting himself to be “nothing but [a] hired flunky. I shall be glad to get back to the line again and will try to do so in the spring. These damn French are bothering us with a lot of details which have nothing to do with any- thing. I have a hard time keeping my patience.”

Patton began to discuss with his wife the possibility of joining the tank corps. “There is a lot of talk about tanks here now and I am interested as I can see no future to my present job,” he wrote. “The casualties in the tanks are high, that is lots of them get smashed, but the people in them are pretty safe as we can be in this war. It will be a long long time yet before we have any [tanks] so don’t get worried. I love you too much to try to get killed but also too much to be willing to sit on my tail and do nothing.”

By early October, Patton met and discussed with Colonel LeRoy Eltinge the role of tanks. Eltinge believed Patton should join them. On October 3, Patton submitted an application to the Tank Service (later called Tank Corps). In the letter, he wrote of his cavalry background, his mechanical ability, and his fluency in French that made him the right man for the job. Showing his usual flair for self-promotion, Patton described his experience during Pershing’s expedition into Mexico, when he had led a small group of men on a raid that took the lives of three Mexican banditos, including Pancho Villa’s chief lieutenant, Julio Cardenas. During the raid, Patton noted, he had used an automobile to help in the surprise attack, adding, “I believe that I am the only American who has ever made an attack in a motor vehicle.”

While waiting for an answer, Patton entered the hospital with a case of jaundice, but he was soon healthy and ready for his new duty. On November 10, he was officially chosen for the Tank Corps and was ordered to prepare a school for light tanks. Orders in hand, Patton wrote his last diary entry as a staff officer: “This is [my] last day as staff officer. Now I rise or fall on my own.”

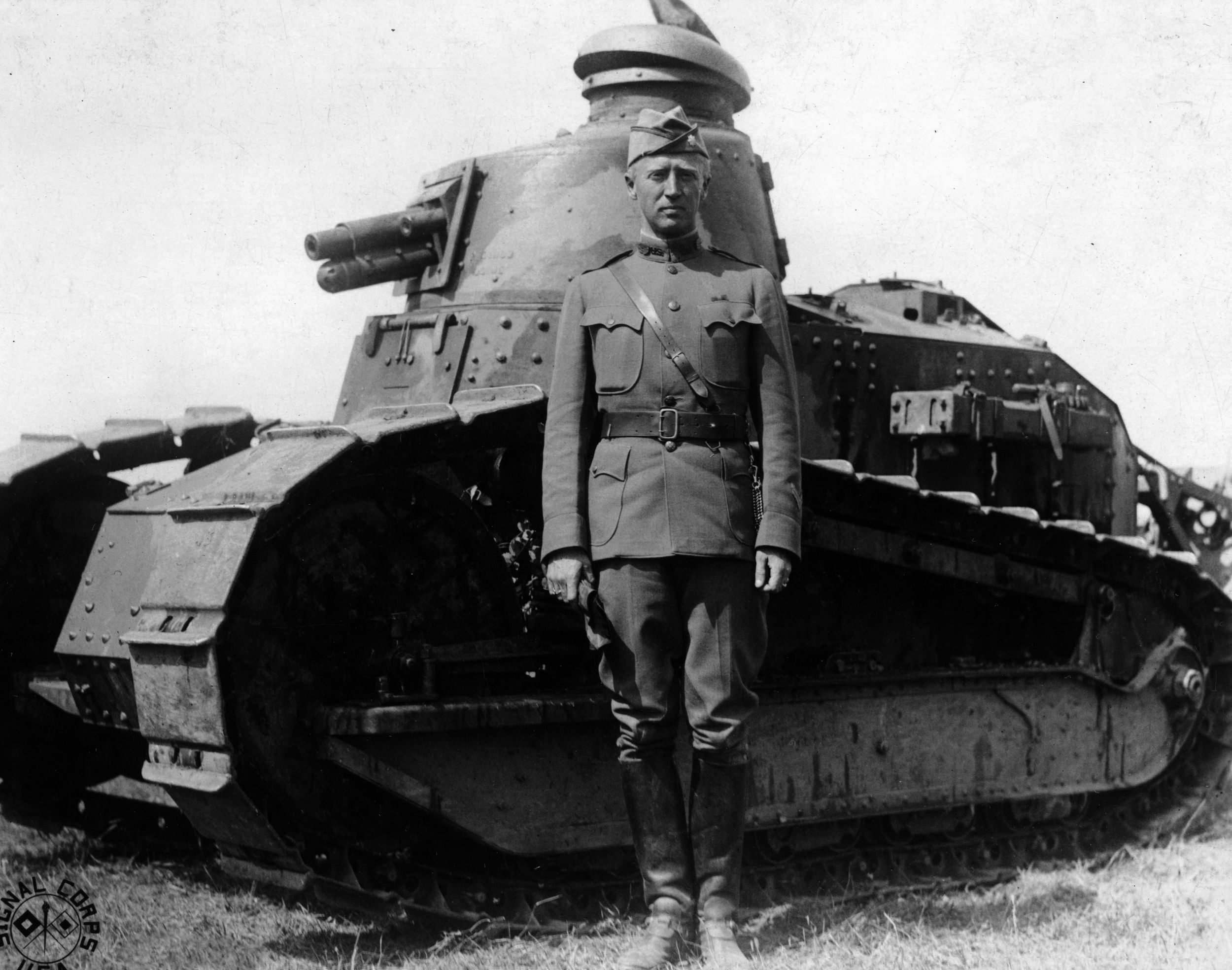

Patton’s First Tank

Patton’s first assignment in the Tank Corps was to learn as much about the tank as possible. In order to begin the American Expeditionary Force Light Tank School, Patton, along with 28-year-old Lieutenant Elgin Braine, was ordered to visit the French tank training center at Chamlieu for two weeks, followed by one week at a tank factory at Bilancourt. Braine, a reserve officer, was originally assigned to the 1st Infantry Division, but was transferred to serve under Patton because of his mechanical and technical expertise. During their weeks studying French light tanks, Patton and Braine made four suggestions that were eventually adopted. These included a self-starter, improvements in the fuel tank to protect against leaks, an interchangeable mount that allowed the tank to carry a 37mm cannon or machine gun, and a steel panel to separate the crew from the engine. While at Chamlieu, Patton drove his first tank, a French Renault. His first impression of driving a tank was that it was easy to control; he thought anyone who could drive a car could operate a tank. In typical Patton fashion, he amused himself by knocking over trees with his new toy.

The Light Tank School

After three weeks of intense study, Patton and Braine began the process of creating the Light Tank School. Before this could happen, the Tank Corps first had to decide which tanks to use. Following a fact-finding mission, the War Department settled on the Mark VII as the nation’s heavy tank of choice. The Mark VII, a close model of the British heavy tank, weighed a massive 43 tons, had an 11-man crew, and a dizzying maximum speed of 6.5 miles per hour. For the light tank, the Americans chose to copy the French Renault. The U.S. model weighed 6.5 tons, with a maximum speed of 5.5 miles per hour and a two-man crew to operate it: a gunner, usually a sergeant, and a driver, usually a corporal. Each tank was equipped with a 37mm cannon or a French Hotchkiss 8mm machine gun. Communicating inside the tanks proved difficult. Completely closed in, with little light seeping through, early tankers devised a primitive but effective way to communicate. Unable to talk because of the noisy engines, the gunner would kick the driver in the back of the head to go forward, a kick on his head to stop, and a kick on either right or left shoulder to go left or right. Prior to the use of radio communication, this was the best the tankers could do.

With heavy and light tanks selected, the Tank Corps began to organize and produce its own tanks. Unfortunately for the Americans, manufacturers at home were ill prepared for the large task ahead—only 26 ever arrived in Europe. To supply the AEF with the tanks it needed, the U.S. government reached an agreement with Allied Commander in Chief Marshal Ferdinand Foch for the transfer of existing light and heavy tanks to the Americans.

With the tanks on order, the Tank Corps had to grow into a fully operational branch of the AEF. Colonel Samuel D. Rockenbach was formally appointed chief of the Tank Corps on December 22. Rockenbach, a graduate of Virginia Military Institute, was 22 years older than Patton and his opposite in almost every way. A stoic, even-tempered figure, Rockenbach lacked a sense of humor and was chosen not for his great mind but for his work ethic. At first, Patton and Rockenbach’s relationship was rocky, and Patton’s first comments on Rockenbach were extremely critical. “Col. R. is the most contrary old cuss I ever worked with,” he wrote. “As soon as you suggest anything he opposed but after about an hours argument comes round and proposes the same thing himself. So in the long run I get my way, but at a great waste of breath. It is good discipline for me for I have to keep my temper.”

Patton’s Armored Tactics

As the Tank Corps prepared to begin training, Patton wrote a paper about light tanks. The 58-page report was, he bragged, “the basis of the U.S. Tank Corps. I think it’s the best Technical Paper I ever wrote.” The paper dealt with the mechanical structure of the tank, the organization of tank units, the tactics of tank forces, and methods of instruction and drill. Patton, while neither a great writer nor a revolutionary thinker, correctly believed that mobility was the most important factor in a tank. Through mobility, he said, the tank could attack quickly, and with its increased speed and maneuverability, the tank would face less fire and be less vulnerable to enemy attacks.

The most insightful aspect of Patton’s paper dealt with tactics and training. While a firm believer in the weapon’s power, he also believed that tanks should function as an aid for infantry. The main tactical value of a tank was to help the infantry advance by running over barbed wire, preventing the enemy from manning trench defenses, shielding infantry from enemy machine-gun fire, neutralizing enemy strongholds, preventing counterattacks, and seizing the initiative and attacking beyond the final objective. While most tanks in World War I were inserted piecemeal, Patton correctly believed that tanks should be employed en masse.

The Training Ground

Finding the land on which to train tankers proved to be difficult. For the training center, Patton chose Bourg, a small village five miles south of Langres. The ground was level and perfect for tank training, and a lone railroad track was beneficial in getting troops and eventually tanks to the center. At first, the French refused to allow the AEF access to the land. This infuriated Patton, who felt that the French were acting more like enemies than allies. “We are more or less held up now by the French who seem to put every obstacle in the way of our getting the ground we want for Tank center,” he groused. “You would think they were doing us a great favor to let us fight in their damn country.” Displaying great diplomatic patience, Patton was able to secure the land, and by January the tank school was becoming a reality.

The next month, Patton learned of his promotion to major. He immediately pinned two golden oak leaves on his shoulders signifying his rank. Unlike most officers during this time, Patton wore his rank proudly and never feared the Germans’ penchant for shooting officers. Soon, he had the tank school up and running. With over 200 men in training at Bourg, Patton provided the best learning environment he could for his troops. Kept busy around the clock, a typical day for soldiers in the tank school began at 8:20 for morning drills, followed by close-order drills, exercises on saluting at 8:35, then calisthenics and fitness drills at 10:05, instruction in guard duty and military courtesy at 10:45, followed by foot drill at 11:20. After recess and lunch, officers were required to receive pistol instruction at 1 pm, followed by machine-gun and foot drill at 1:50 and theory and operation classes from 2:50 to 4. The rest of the day, the soldiers were expected to keep the training center in shipshape order.

Patton “Ruled an Ass” in England

In March, Patton and Rockenbach spent a week in England attempting to get some modifications for their tanks. “I argued in favor of four speeds,” Patton recalled, “but was ruled an ass.” Following the trip, Rockenbach made his first inspection of the tank school and was extremely impressed. After the visit, Patton was in rare form, giving a speech on discipline. “Lack of discipline in war means death or defeat, which is worse than death,” he warned. “The prize for this war is the greatest of all prizes—freedom. It is by discipline alone that all your efforts, all your patriotism, shall not have been in vain. Without it heroism is futile. You will die for nothing. With discipline you are irresistible.”

On March 19, Patton received word that he had been promoted to lieutenant colonel, and he was further elated to hear that 10 Renault tanks were on their way to Bourg. Following a few weeks of training with actual tanks, he and his troops put on their first demonstration on April 22. The demonstration went extremely well, and Patton noted, “The show came off all right except that it was raining hard and very cold so that one got stuck in a shell hole but I had a reserve one ready and every thing went on fine.” To celebrate the school’s success, six days later Patton organized the 1st Light Tank Battalion, with himself as battalion commander.

While happy with the tank school’s progress, Patton grew bored with the safety of rear duty and longed for a glimpse of the front. “I am getting ashamed of myself when I think of all the fine fighting and how little I have had to do with,” he told his wife. On May 21, he finally had a chance to travel to the front. Traveling with a French major named La Favre, Patton once got within 200 yards of the German line. Willing to risk his life for a bit of fun, La Favre turned sarcastically toward the German line and exposed his bottom to enemy fire as he adjusted his leggings. Patton, not to be outdone, took off his helmet, lit a cigarette, and began to smoke. Luckily for both La Favre and Patton, German sharpshooters disdained to fire on the two show-offs.

Returning from his trip, Patton reorganized the tank school and formed a second battalion. As the equivalent of a regimental commander, he appointed a chief of staff, adjutant, reconnaissance officer and supply officer. He placed Captain Joseph Viner in command of the 1st Battalion, also named the 344th Tank Battalion, and Captain Sereno Brett in command of the 2nd Battalion, also named the 345th Tank Battalion. In June, Patton accepted a spot at the Army General Staff College in Langres. While busy with the tank school and not really interested in staff duty, he decided to take the class because most general officers had taken it. On August 20, while still in class, Patton received an urgent message: “You will report at once to the Chief of Tank Corps accompanied by your Reconnaissance officer and equipped for field service.” For Patton, it was a dream come true. For the first time in his life, he would lead large numbers of men into battle.

First Major Engagement of the American Expeditionary Force

By the late summer of 1918, the AEF had grown large enough to participate fully in the war. Although divisions had been pushed into battle to stop the German summer offensive, the St. Mihiel attack would be the first major engagement the AEF would participate in as a whole. Located 20 miles southeast of Verdun, the town of St. Mihiel had fallen into German hands in 1914. Four years later, the Germans still held on to 150 square miles of French territory. While cutting off the salient was important, the real prize was the ancient fortress of Metz, 30 miles beyond St. Mihiel. The original plan called for an all-out attack on St. Mihiel, with 15 American divisions and four French divisions moving against the flanks of the salient.

Unfortunately, French and British fear caused a change in the plan. Supported by Foch, Haig believed that a complete breakthrough of the St. Mihiel salient was risky and unnecessary. Instead of pushing forward with a breakthrough, the armies would stop and prepare for the major engagement against the Hindenburg Line. The new plan called for the forces to free the railroad through St. Mihiel to Verdun and to establish a base for further operations. After cutting off the salient, the AEF would reorganize and swing north to the Meuse-Argonne Hindenburg Line.

Patton set out to see the terrain on which his beloved tanks would fight. During the last week of August, Patton and some French soldiers explored the section designated for the Tank Corps. Patton found the ground soft, but he decided that it was suitable for tank use. With this knowledge in hand, he set about devising his own plan for his tanks. The plan called for Patton’s 1st Tank Brigade to support the 1st and 42nd Divisions, which were located almost directly in the center of IV Corps. Meanwhile, the AEF received 225 light tanks from the French. Out of the 225 light tanks, Patton got 144 of them and planned to put them all to use. Before going into battle, he gave another grandiloquent speech. “American tanks do not surrender,” he roared. “As long as one tank is able to move it must go forward. Its presence will save the lives of hundreds of infantry and kill many Germans. Finally, this is our big chance. Make it worthwhile.”

Patton on the Front Lines

The day of attack arrived. On September 12, 550,000 doughboys and 3.3 million artillery rounds launched their attack on the St. Mihiel salient. Patton wrote in his diary, “When the shelling first [started] I had some doubts about the advisability of sticking my head over the parapet, but it is just like taking a cold bath, once you get in it’s all right. And I soon got out on the parapet.” By 9:15, Patton was growing weary of staying behind the lines. The excitement of the battle and the urge to prove his courage were too much for him to ignore. He decided to leave his command post and see for himself what was going on.

Patton moved on foot toward the action and immediately saw the wrath of war as the dead lay scattered across the field. As for his tanks, he came upon a few stuck in the mud and trenches, but in general the tanks were performing well. Patton eventually met up with some French tankers under his command around the town of St. Baussant, and he also encountered Brig. Gen. Douglas MacArthur, commander of the 84th Brigade. The two conversed on a hill as bullets whizzed by. “I joined him and the creeping barrage came along toward us,” Patton recalled. “We stood and talked but neither was much interested in what the other said as we could not get our minds off the shells.” One well-placed artillery round on that cold, rainy, September day could well have changed the course of World War II.

After talking with MacArthur, Patton moved on toward the action. In Essey, he met some American soldiers who were afraid to cross a bridge a French soldier had told them was mined. “This made me mad,” Patton said, “so I led them through on foot but there was no danger as the Bosch [was] shelling the next town.” After crossing the bridge, he hitched a ride on a nearby tank. A few miles out of town, while still on the top of the tank, Patton noticed paint chips beginning to fly off the tank—he couldn’t hear anything over the noise—and immediately jumped off the vehicle into a shell hole. Unfortunately for Patton, the tank crew did not notice his hurried departure and went on, leaving him in a wide-open field with infantry troops still 600 yards behind. Stuck in the shell hole, Patton again pressed his luck. “The bright thought occurred to me that I could move across the front in an oblique fashion and not appear to run from the Germans yet at the same time get back,” he recalled. “Finally I decided that I could get back obliquely. So I started listening for the machine guns with all my ears. As soon as the m.g.’s opened I would lay down and beat the bullets each time. Some time I will figure the speed of sounds and bullets and see if I was right. It is the only use I know of that math has ever been to me.”

After his narrow escape, Patton rejoined the infantry and began organizing an attack of the town of Beney. Around 3 pm, exhausted and content with the progression of the battle, he sat down for his first meal, only to find that a mischievous German POW had replaced the food in his hamper sack with rocks. He made do with some crackers taken from a dead German. Following the successful attack on Beney, both the 1st and 2nd Tank Battalions settled in for the night. The next day, Patton and his tanks moved forward against little German resistance. On September 14, his forces pushed aside German resistance and captured the town of Jonville.

For the Allies, the battle of St. Mihiel was a tremendous success. More than 16,000 Germans were captured, along with 450 guns; and more than 7,000 Germans were killed, wounded, or missing. Only a few hundred American deaths were reported. Of Patton’s 174 tanks engaged in the battle, three were destroyed, 22 were ditched, and 14 broke down. With only five killed in action and 19 wounded, Patton’s tank forces had done extremely well. The performance of the tanks, while far from perfect, proved to doubters that tanks were an important and powerful weapon, not just a laboring machine.

Patton believed that he and his forces had done well but could do better. Personally, Patton had shown great courage under fire and tremendous leadership qualities. Rockenbach, however, believed Patton’s conduct during the battle was less than exemplary. As a tank brigade commander, he felt that Patton’s duty was at headquarters, not running around in a field chasing tanks. In Rockenbach’s reprimand of Patton’s conduct, he listed three points: “1. The five light tanks of a platoon had to work together and not be allowed to be split up. 2. When a tank brigade was allotted to a corps, the commander was to remain at the corps headquarters or be in close telephonic communications with it. 3. I wish you would especially impress on your men that they are fighting [with] tanks, they are not infantry, and any man who abandons his tank will in the future be tried.” Patton’s personal leadership during the battle endeared him to his soldiers. While Rockenbach considered Patton’s wandering off to the front line a weakness, others considered it a strength. “George Patton was always on the front lines, never in the rear with the Red Cross,” wrote Captain Viner. “That was one of the secrets to his greatness.”

“To Hell With Them, They Can’t Hit Me!”

With the St. Mihiel salient closed, the AEF immediately readied itself for the next move, the Meuse-Argonne offensive. For that attack, 10 divisions planned to attack in the first wave, while eight others waited in reserve. Collectively, the AEF faced 18 well-trained German divisions. Following an artillery bombardment, the American forces were to attack a 20-mile-wide, 13-mile-long area. Throughout the area were countless German defense fortifications, dugouts, and other obstacles. Patton devised a plan for a concentrated tank thrust through the enemy defenses. The 1st Tank Brigade was ordered to support the 28th and 35th Divisions of I Corps as they attacked from the west. The two units would break out of the line and advance as far as they could.

The attack started on September 26 as the artillery bombardment broke through the heavy fog. Around 6 am, Patton seemingly disregarded Rockenbach’s advice and reprimand and left his command post to see how his tanks were performing. Once again traveling on foot, Patton followed tank tracks on the Clermont-Neuvilly-Boureuilles-Varennes road, and after a few kilometers met up with some of his tanks. Almost immediately German artillery shells hit and were followed by machine-gun fire. After ordering everyone to hit the dirt, Patton ordered all ground troops toward a railroad cut.

Once in the safety of the cut, Patton waited for the firing to end. While waiting for the attack to subside, more and more infantry troops began running from the front, seeking protection in the cut. With the attack dying down, Patton noticed tanks stopped before a large trench. Seizing a lull in the German bombardment, he organized the infantrymen and marched them to the trench. As they approached the trench, Patton ordered all to hit the dirt again, as machine-gun bullets flew over their heads.

After the fire died down again, Patton immediately ordered the men to help get the tanks across the trench, and the men began to tear down the trench walls. The Germans began another barrage, and machine-gun fire burst out from the front. Unmoved by the firing, Patton ordered his troops to hold their ground and continue digging. While some continued to dig, others fled back to the railroad cut. Patton, angry at their lack of courage, continued to dig and even hit a few soldiers over the head with a shovel to keep them working. With the fire increasing and more troops falling on the side of him, he pushed forward, yelling, “To hell with them, they can’t hit me!”

Finally the tanks advanced past the trenches, and Patton readied himself and his motley group of soldiers to advance. Waving his big walking stick over his head, he tried to rally the troops and shouted, “Let’s go get them! Who’s with me?” Caught in the moment, 100 soldiers jumped to their feet and ran down the hill with Patton. German machine-gun fire increased fantastically, causing Patton and his soldiers to hit the dirt after only 50 yards. With machine-gun fire growing stronger by the minute, Patton had a sudden vision: “I felt a great desire to run, I was trembling with fear when suddenly I thought of my progenitors and seemed to see them in a cloud over the German lines looking at me. I became calm at once and saying aloud, ‘It is time for another Patton to die.’ [I] called for volunteers and went forward to what I honestly believed to be certain death. Six men went with me; five were killed.”

Patton quickly picked himself up, waved his walking stick, and shouted to the six men following him, “Let’s go, let’s go!” As the other men quickly fell, Patton’s orderly, Private First Class Joseph T. Angelo, wondered what the lunatic was trying to prove, armed with only a walking stick. Forced to take cover with Angelo in a shell hole, Patton once again tried to advance. A few seconds later, he felt a shock of a bullet enter his leg. Struggling to move, Patton managed to crawl back in the shell hole with Angelo. Angelo managed to bandage his wound, and the two awaited help. After a few hours, the fire abated and Patton, still conscious, was placed on a stretcher and taken to the medic tent.

Injured and suffering from massive blood loss, Patton ordered the medics to take him to the 35th Division headquarters so he could give his report of the front. After reporting to the headquarters, Patton was sent to Hospital Number 11 for immediate surgery. The next morning he awoke, dazed but otherwise feeling rather good. The bullet had entered his left thigh and exited two inches to the left of his rectum. Patton wrote home to tell his wife that he was “missing half my bottom but otherwise all right.”

Once again, Patton’s tanks proved their worth. Overall the two battles, St. Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne offensive cost the AEF 117,000 casualities, but they inflicted 100,000 casualties on the enemy while 26,000 prisoners, 874 cannons, and 3,000 machine guns were captured. The two battles helped push the Germans to the brink of defeat. For Patton, however, the war was over.

“Col. Patton, Hero of Tanks”

A few days after being wounded, Patton was proud to read stories of his death-defying exploits. The headline of one story read, “Col. Patton, Hero of Tanks, Hit by Bullet—Crawled into Shell Hole and Directed Monsters in Argonne Battle.” While thrilled with what he had done so far, Patton was slightly depressed, writing to his wife, “I feel terribly to have missed all the fighting.” Bored with hospital life and frustrated by not being able to fight, he was cheered by another promotion—this time to colonel. To his immense gratification, he was also awarded both the Distinguished Service Medal and Distinguished Service Cross, and he wore them with pride for the remainder of his life.

The war ended while Patton was still recovering, and he noted almost sadly in his diary: “Peace was signed and Langres was very excited. Many flags. Got rid of my bandage.” After getting out of the hospital and writing his numerous reports, Patton returned to his tanks, but without the war his job was boring, and he was saddened as many of his soldiers left for home. He remained in France for months after the war, and he prepared to leave with his brigade around March. Patton left aboard the SS Patria on March 1 and arrived in New York with much fanfare on March 17, 1919. Swamped by numerous newspaper reporters, Patton was quoted in the New York Evening Mail as saying, “The tank is only used in extreme cases of stubborn resistance. They are the natural answer to the machine gun, and as far as warfare is concerned, have come to stay just as much as the airplanes have.”

The war was over, the Allies had won, and Patton had surpassed all expectations. The beginning of the Patton legend was born. World War I reinforced what Patton had trained his whole life to become, a battlefield commander. The Great War showed him for the first time to be a fine officer and leader of troops. Almost single-handedly, he had created a tank school and trained the 1st Tank Brigade. He had learned how to command and motivate troops and, ultimately, how to lead them in combat. Everything Patton did in World War II started in World War I. Indeed, it is hard to imagine General Patton rolling victoriously across Germany in 1945 had not Colonel Patton first slogged through the mud in France in 1918.

The tank the author identifies as a “Whippet” north of Verdun is actually one of Patton’s Renault FT-17s. I know because I used that photo in my book about the WWI Tank Corps: “Treat ‘Em Rough!: The Birth of American Armor, 1917-20” (Presidio, 1990; Casemate, Ltd., 2d rev. ed., 2018).