By Glenn Barnett

The 90th Heavy Bombardment Group, known as the Jolly Rogers, was an element of the Fifth Air Force headquartered in Brisbane, Australia. During World War II it played a crucial role from the Battle of the Bismarck Sea to Leyte Gulf. The Jolly Rogers crippled enemy airpower on the ground and in the air. Their 100- and 2,000-pound bombs were used in support of Allied beach landings and against enemy shipping and airpower. A sign hanging beneath the squadron name proclaimed it to be “The best damn heavy bomb group in the world.”

Herbert Goodrich, a farm boy from Nebraska, enlisted as a cadet in the Air Corps in 1942. He became a B-24 pilot assigned to the 90th and flew 63 combat missions against Japanese targets in New Guinea.

[text_ad]

Glenn Barnett: Where and when were you born?

Herbert Goodrich: I was born in 1919 in Fairmont, Nebraska. My father was a farmer, and we lived on 240 acres where we raised wheat, oats, and alfalfa. We had hogs and cattle. All the chores were done with horses until Dad finally got an Allis Chalmers tractor in 1937 for $800. That was the best day of my life at that time.

GB: When did you see your first airplane?

HG: I was about 12 or 14 when an old barnstormer set down in our field. At that time you could take a ride for about $2.50. My father gave me the money for the ride. In high school we went into Lincoln, Nebraska, and paid $5.00 for a ride. Later a plane landed on our field, and the pilot negotiated with my father for some tractor gas. He gave us a ride in exchange.

GB: Where were you when you heard about Pearl Harbor?

HG: We had just gotten home from church. We were getting ready for dinner. We didn’t have the radio on so we didn’t know. A neighbor family came over and told us. We listened to the news for the rest of the day.

GB: Were you drafted?

HG: The Army was going to draft me, but I didn’t want to be in the trenches, so I applied to the Air Corps to be an aviation cadet. There were 150 questions on the test, and you had to answer 90 of them correctly. I got a 113. A friend of mine got an 89. He missed it by one and ended up handling cargo in the South Pacific. I was sworn in as a private in the Air Corps on March 23, 1942, down in Omaha.

GB: What was your basic training like?

HG: From Omaha I entrained for the air base at Santa Ana, California. It was our assignment center. We arrived there on April 14th. We lived in tents, and it rained like the devil in April. We did a lot of close-order drill. I took some tests and was classified as a pilot. On May 28th I was assigned to Rankin Aeronautical Academy in Tulare, California. I finally soloed on June 18th. We flew Boeing PT-17 Stearmans. It was a little biplane with a 220-horsepower Continental engine. After the war they were used as crop dusters.

I scraped a wing on my second solo flight. I figured I was washed out, but they let me pass. In total I had 50 hours flying time at Tulare. It was a tough school, and 44 percent of my class washed out. They were reassigned as navigators or bombardiers.

I was then sent to basic training in the hot months of July and August. We did some formation flying, night flying, and cross-country trips. Two of my friends were flying on instruments when their plane stalled on approach and they crashed and burned. It was a sad moment. At the end of the training I got my lieutenant’s wings.

GB: Were you assigned to bombers?

HG: No they asked us if we wanted to fly pursuit planes or twin engines, and I chose the twin engines. In October I was assigned to Stockton [California] where we trained in AT6s and AT0-20s. I soon soloed in a Cessna AT-17. We had additional training in Salt Lake City, Utah, and Alamogordo, New Mexico. That is where we first flew the B-24 bomber. I had never seen one and didn’t know anything about it. My first impression was that it was too damn big to fly.

GB: What were the B-24’s strengths and weaknesses?

HG: It had the Pratt and Whitney engines. In my opinion it was a better engine than the Curtiss Wright that the B-17 had. However, it had no auto throttle control. I never flew the B-17, but one friend said it flew like a cub while the B-24 flew like a truck. You had to manhandle the controls. You wouldn’t want to ditch in the ocean in a B-24 either. The nose tended to separate from the fuselage.

GB: When did you meet up with your crew?

HG: I arrived in Alamogordo in December and trained there. It was a pretty cold winter. Some of the crews were sent to Topeka, Kansas, to train. En route two of them had their wings ice up in flight and they had to bail out. One of my friends was killed when he didn’t get out in time.

GB: When were you sent overseas?

HG: I got back from leave a day late so they sent our plane to North Africa. I heard that it later took part in the raids on the Ploesti oil fields in Romania. But we were sent to the Southwest Pacific. We had all of our fur-lined coats with us. There would be quite a pile of abandoned fur-lined coats in New Guinea. At about 9 pm on March 18, 1943, we took off from the west coast for Hawaii. Our plane was the “Double Trouble.” There were 11 B-24s and a number of B-25s [medium bombers] with us. We watched as the lights of San Francisco disappeared behind us. We leveled off at about 8,500 feet and flew for 15 hours before reaching Hawaii. We had a little fuel scare for a time because of a misreading of the fuel gauge, but all the planes made it with fuel to spare.

From there we flew to Christmas Island. The poor soldiers there had a faraway stare in their eyes and begged us for any kind of liquor we might have. Some of them had been there for 14 months even though they were supposed to rotate out every six months. There was little to do there, and we felt sorry for them. From Christmas Island we flew to Canton Island. It was well fortified and subject to night bombings by the Japanese, but they did little damage. The night before we got there they bombed the island, and the only casualty was a dog. From there we flew to New Caledonia and then to Australia, arriving on March 24th. We soon discovered that Australian beer was not only good tasting but also very potent. We arrived in New Guinea in April.

GB: So you missed the Battle of the Bismarck Sea?

HG: Yes, but you know every time a new crew came in the old timers would say, “You should have been here when it was rough.”

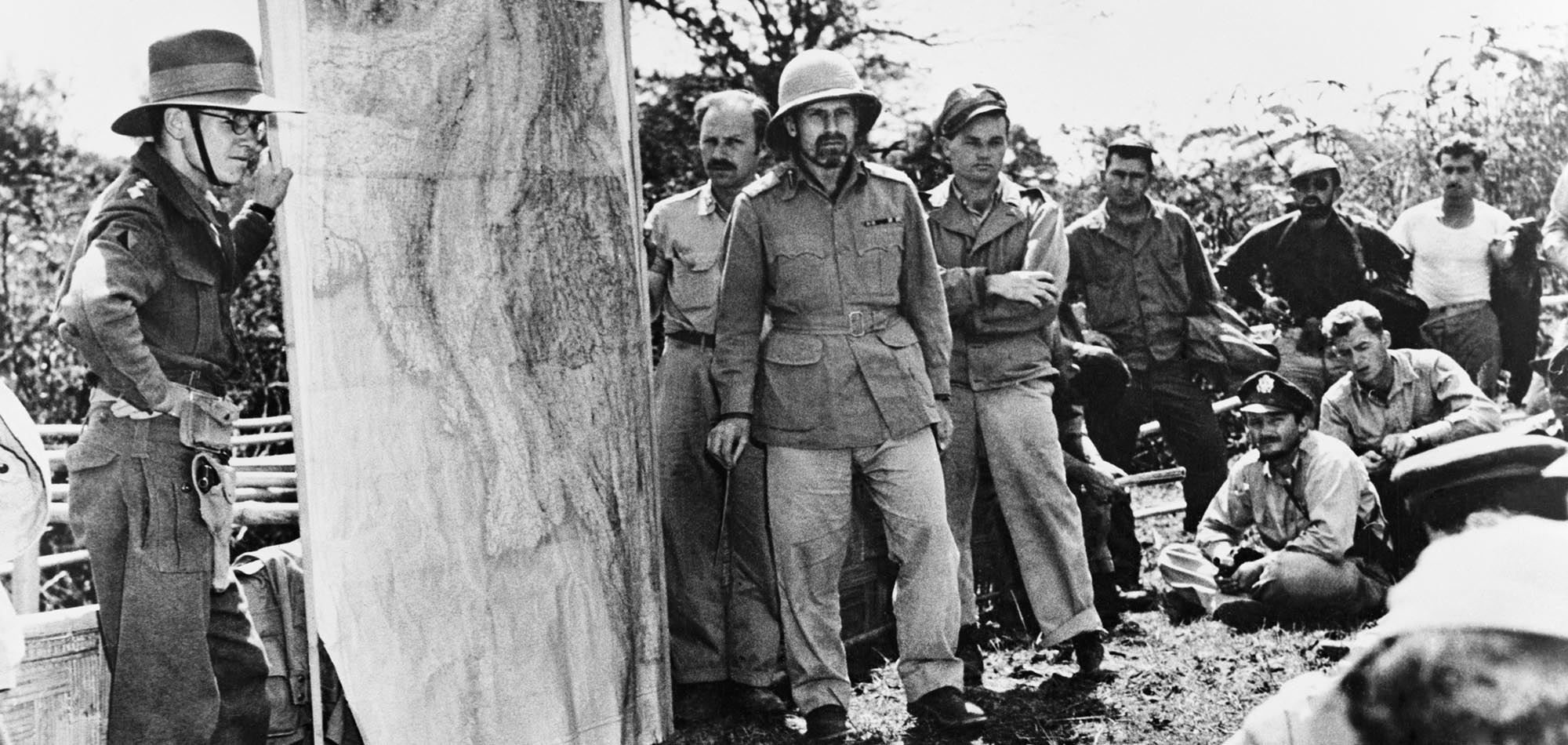

GB: You were assigned to the 90th Heavy Bomb Group?

HG: Right. We were called the Jolly Rogers after our commanding officer, Colonel Art Rogers. Our insignia was a skull with crossed bombs underneath it. I was in the 320th Squadron. Our squadron insignia was a shark with a twin tail like the B-24s. There were four squadrons in the group. Each squadron had about 12 airplanes. Our planes had an initial takeoff weight of 64,000 pounds, but later models could lift off with 72,000 pounds.

GB: Most of the planes sent to Australia were modified. Was yours?

HG: Yes. They took off the de-icing equipment and an alcohol tank. They had also found a way to put a tail gun turret on the nose of the plane. This gave us tremendous extra firepower forward. Colonel Rogers originally came up with the idea. With the help of a brilliant mechanic named Colonel Paul I. “Pappy” Gunn, the turret modification was made to work. Gunn had been an airline pilot in the Philippines before the war. He was able to successfully mount the turret in most of our B-24s. Gunn was responsible for a lot of innovations that improved our fighting and flying capacity. It was at this time that they took Double Trouble away from us and gave it to another crew.

GB: How did the nose turret work out?

HG: Real well after they perfected it, but once we wanted to see what the red line was on the air speed when we dived. We just about got to that point in our dive when a helluva racket let loose and something flew by the cockpit. The pin that held the nose turret centered sheared off. The turret fell sideways, and the doors fell off of it and ripped the side of the fuselage.

GB: Is it true that General George C. Kenney [commander of the Fifth Air Force] was initially reluctant to accept the B-24s and liked the B-17s?

HG: Well, he might have been. I never flew the B-17, but it was supposedly easier to fly. The B-24 had no automated controls; we had to control it by hand, so we really gave our arms a workout adjusting it. It did have an autopilot, but if we were flying close formation we couldn’t use it.

GB: When you were flying missions did you ever run into enemy fighters?

HG: Yes! Over Wewak they came in a time or two, but they peeled off. During our first daylight raid on Rabaul they came in. They got above our top turret gunner. His guns jammed. That was a long 30 seconds before he got it clear. We were following the commanding officer of the squadron. We were supposed to drop our bombs following the lead of his bombardier. But his bombs hung up, and so we were late and dropped them in the water.

GB: Did you come home with holes in your plane from flak?

HG: We got a little flak over Lae one time, and one of my waist gunners was wounded by some flak. I was really lucky. We never got too much flak and never got caught by the weather. I was on leave in Australia during Black Sunday. [Note: On Sunday, April 8, 1944, during a bombing raid over Hollandia, a weather pattern closed down all the Allied airfields in northern New Guinea. As a result, 31 planes were lost, only four to combat, the worst day of the war for the Fifth Air Force.]

GB: What was your first mission?

HG: It was to Salamaua near Lae [New Guinea]. It was a missionary village. We dropped some bombs in there. We flew a number of missions out of Port Moresby supporting the landings at Lae. Then we started hitting Wewak. We had some losses there. A friend of mine came home with a bullet-riddled plane, but his gunners shot down five Zeros [Japanese fighters] in the process.

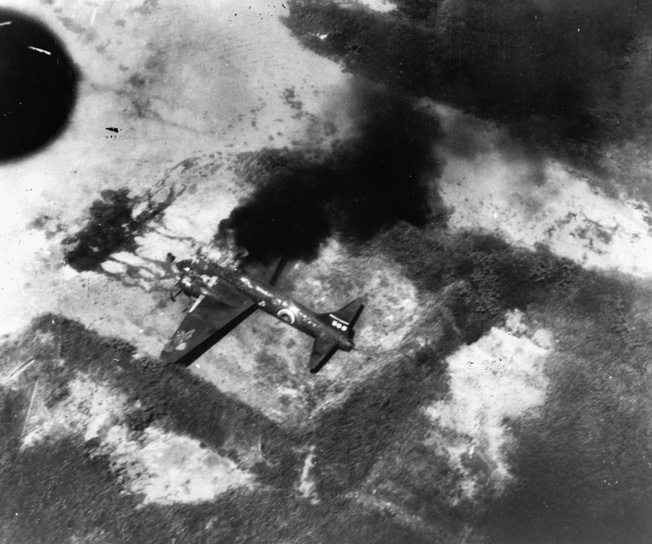

One of our missions was reconnaissance, looking for shipping. But it was very long range from Port Moresby. They loaded the planes with 3,100 gallons of gas and a 20,900-pound bomb load. A 403rd Squadron plane loaded like this had just lifted off when it crashed into an Aussie camp, killing several Australians and the crew.

GB: Were there a lot of accidents?

HG: I’m afraid so. I remember a waist gunner shot up his own outboard engine. He was embarrassed. New Guinea had unpredictable weather. In the afternoon the clouds formed up over the mountains and reached as high as 40,000 feet. We had to fly through or fly around. We had one crew that flew around the clouds to bomb Rabaul, and they ran out of fuel before they got back. Weather probably accounted for more of our casualties than the enemy. Several planes crashed into mountains. Others hit trees on approach or takeoff.

GB: The B-24 carried a lot of firepower, didn’t it?

HG: We had two .50-caliber guns in the tail, two more in the top turret, one on either side of the fuselage used by the waist gunners, and two in the nose. By mid-September 1943, our group [90th Bomb Group] claimed 39 kills. Our squadron claimed 22 Zeros shot down. The P-38 [fighter] pilots who flew cover for us took issue with this as they claimed some of the same kills that we did.

GB: Lae fell in mid-September. What did you do next?

HG: By mid-October we began the dreaded raids on Rabaul, which was well defended. At first we flew at night for reconnaissance and to harass them. We dropped our bombs to keep them awake. Sometimes we just tossed out empty Coke bottles, which made a terrifying whistle.

On the first daylight raid, I flew in a formation of six planes looking for shipping. Four of them had to turn back because of mechanical problems, but we kept going. Over the target our bombs hung up and wouldn’t release. We tried to line up again but after eight passes from Zeros we dropped our bombs in the sea and headed home.

GB: What happened when you returned to base?

HG: They had an intelligence officer who would ask us what we saw, how much activity, how the flak was, the weather, any fighters. Then sometimes they gave us a shot of whiskey. Once we had a squadron photographer who wrote to his mother about the whiskey. She was from the Bible Belt in Texas and was upset. She didn’t go through channels but wrote directly to President Roosevelt that her son was being ruined. Then it came down through channels, and he had to have a candy bar after his missions. He was a funny character.

GB: You got leave after the raid on Rabaul?

HG: We flew down to Sydney for six days and then back to Brisbane. They gave us a new airplane there. Then we met some fighter pilots who wanted to get back to New Guinea, as well as some of our own ground crewmen. With our own crew of 10 we had 22 men aboard. In addition, someone loaded 75 cases of beer in the bomb bay. Because the ship was new to us, we had 2,800 gallons of gas, 400 gallons more than we thought there was. We were grossly overloaded.

Our takeoff roll was slow, and we really struggled to get airborne. But we clipped our right wing on a tree, which tore away the leading edge. So, we circled back and landed. The fighter pilots had seen enough of bombers and liked the quiet life in a P-40 [fighter]. Two days later, when we had a new B-24, they started betting among themselves that we wouldn’t get off the ground.

While we waited for the fighter pilots to get back to Port Moresby, I hitched a ride up to Lae to see our new air base there. While I was there, I collected some souvenirs from wrecked enemy planes.

GB: When did you get back into action?

HG: On December 1 we were a part of a raid to Wewak. It was supposed to be a gravy run, but Japanese naval air pilots jumped us. We lost three B-24s that day. Only six men of the three crews survived. It was the 90th’s worst day in combat.

GB: Port Moresby was far from the front by this time?

HG: That’s right. We started moving forward to Dobodura on December 22. We used the bombers to transport our equipment. We flew three flights over on Christmas Day and missed the chicken and ice cream supper that evening. We did have a little liquor left from the club, and it was one very drunk night out. After Christmas we made three more runs of equipment to Dobodura and then went to Australia.

GB: What did you do in Australia?

HG: We flew to Melbourne to do some practice bombing with aerial burst bombs for Pappy Gunn. He had developed a bomb that would explode about 200 feet in the air. It was supposed to catch the Japanese soldiers in the trenches. The bombs were part of a project he was working on. I don’t think they amounted to much. I didn’t see them again. We were in Australia for a week and had a great time.

GB: American bombing raids caught a lot of Japanese planes on the ground. Why was that?

HG: Their communications weren’t very good, and they were short of pilots. Then too, they might have had fuel shortage problems. The Germans did.

GB: You didn’t always have visibility over the target?

HG: We flew usually around 10,000-20,000 feet. Once we were over Rabaul, we found that it was socked in with clouds. The navigator told me that it was down there. I said “Drop a flare!” He said, “What good will that do?” I said, “Drop it anyway.” We dropped the flare, and the whole sky lit up. They started shooting, but they were shooting at the flare. A number of times we’d be over the target in the clouds. We killed a lot of fish.

GB: Did you arm the bombs in flight?

HG: The bombardier armed the bombs after we were airborne. He would set up his bomb sight for the expected height and airspeed. He could couple into the autopilot, but it was pretty erratic. So most of the time we flew the needle ourselves. One of the other pilots said of his bombardier that he couldn’t hit the earth if it weren’t for gravity.

GB: Did you ever bring your bomb load back to base?

HG: The bombardiers would say “drop the … bombs.” But I always thought they cost money. So, if we had a secure load we would bring them back if we couldn’t reach the target.

GB: A lot of soldiers got sick in New Guinea. Did you?

HG: Toward the end of my combat flying, I came down with a bad fever and was hospitalized. I was afraid it was malaria, but it turned out to be dengue fever—not as bad but still no fun. I spent a month in hospital. Shortly after, I had my 397 hours of combat flying and could rotate home. I got home in February of 1945.

GB: What was the highest rank you attained?

HG: Captain. I started out as a second lieutenant. The Air Corps promoted guys because they claimed that the Germans recognized rank. If you got shot down, a tech sergeant was treated a lot better than a staff sergeant, so they made tech sergeants out of a lot of the crew members. Of course, it didn’t make much difference to the Japanese.

In recognition of his service, Herbert Goodrich received the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal. His combat flights totaled more than 400 hours. After the war, he worked as a pilot for United Airlines for 33 years.

Originally Published September 2010

Truly an Amazing American Hero and Human!