“This is Berlin calling the American mothers, wives and sweethearts. And I’d just like to say, girls, when Berlin calls it pays to listen.”

So began a typical address by Nazi propaganda radio broadcaster Mildred Gillars, known as Axis Sally, during World War II. Her program was filled with hateful rhetoric directed against U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and the Jewish people. Her radio broadcasts were heard not only by U.S. soldiers fighting Nazi Germany, but also by Americans in the States.

“A defeat for Germany would mean a defeat for America,” she said. “I say damn Roosevelt and Churchill, and all of their Jews who have made this war possible. I, as an American girl, will stay over here on this side of the fence because it’s the right side. Girls, watch out! Don’t forget the beautiful things we have at home which are now in danger.” Gillars’ theme song was the German hit “Lili Marlene,” which became a favorite with soldiers of all the fighting armies of both sides.

Her Start at German State Radio

Hundreds of thousands of American servicemen in North Africa, the Mediterranean, and northwestern Europe listened to her broadcasts from 1943 to 1945 at the height of World War II. They instantly recognized both her distinctive voice and appealing format that encompassed Big Band-era tunes played by a live orchestra.

Gillars began working at the German State Radio in 1940 as an announcer. At the time she was living in Germany with her fiancé, who was a naturalized German citizen. He threatened to leave her if she returned to the States, so she stayed in Germany despite advice the following year from the U.S. State Department that American nationals return home.

Her broadcasts initially were apolitical. Gillars’ main Nazi program included the Home Sweet Home Hour, which was designed to discourage homesick Americans from fighting against Germany via implied unfaithfulness of their wives and girlfriends stateside, as well as disparaging the war’s purpose and the Allies’ ability to win it. Other programs were Club of Nations, Smiling Through, Morocco Calling, Christmas Bells of 1943, Easter Bells of 1944, and Survivors of the Invasion Front.

During the course of her on-air work, she interacted with German radio’s Hans Fritzsche, who was later tried and acquitted at the Nuremberg Trials, and Kurt Georg von Kiesinger, the station’s liaison with the German Propaganda Ministry for Overseas Broadcasting. Kiesinger became the chancellor of West Germany in 1966.

Another program, Midge at the Mike, ran from spring to fall 1943. After D-Day in 1944 came yet another major program, known as the G.I.’s Letter Box and Medical Reports, which had at its core the actual names, individual service numbers, and current prisoner of war status of wounded American soldiers. The relatives of captured soldiers listened to the program regularly.

One key listening post in the States was the U.S. Federal Communications Commission’s monitoring facility at Silver Hill, Maryland, which duly recorded as much of it as possible for an expected postwar judicial reckoning when the Nazis lost.

On the widely scattered battlefronts, the mystery female announcer’s identity soon became cloaked in a variety of nicknames, such as Berlin Babe, Berlin Bitch, Olga, and Sally. The last one, which morphed into Axis Sally, became her most lasting nickname. It stemmed from her self-description as “the Irish type—a real Sally—with a figure, black hair, white skin. I think I’m just an armful.”

“No Other Gal But Sal”

“Sal is a dandy,” wrote U.S. Army Air Corps weatherman Corporal Edward Van Dyne, in a January 1944 article, “No Other Gal but Sal,” in The Saturday Evening Post. “[She is] the sweetheart of the American Expeditionary Force! She plays nothing but swing—and good swing! She has a voice that oozes like honey out of a big wooden spoon. ‘Homesick, soldier? Throw down your gun and go back to the good old USA.’ Dr. Goebbels no doubt believed that Sally is rapidly undermining the morale of the American doughboy. I think the effect is directly opposite. We get an enormous bang out of her. We love her. Well, Sally, we’ll be in Berlin soon, with a great big hug for you, if you have any kisses left!”

Undoubtedly, her most infamous broadcast was titled Vision of Invasion on May 11, 1944, in which she played an Ohio mother named Evelyn, who in a nightmare foresaw her son’s death on an Allied ship in the English Channel during what she described as a failed seaborne invasion of Nazi-occupied France.

Indeed, it was this singular broadcast, which garnered one of 10 postwar counts of treason, which saw her both convicted and imprisoned for having committed treason against the United States. She was a lifelong citizen of the United States despite having sworn in writing an oath to German leader Adolf Hitler on December 9, 1941, under later alleged duress, just two days before Nazi Germany declared war on America.

Failing to remain in Paris in August 1944 just 10 days before the Allied liberation that would have freed her, Axis Sally instead fled back to Berlin, where she gave her last broadcast on May 6, 1945, literally exiting her radio station by its back door as Red Army soldiers entered through the front, according testimony she gave at her postwar trial. Two days later, the shattered Third Reich surrendered, and Axis Sally went underground, using the alias Barbara Mome until she was arrested by a U.S. agent in March 1946.

Her real name finally emerged upon her arrest, and more dramatically again when she arrived in Washington, D.C., for a criminal trial as an accused traitor in 1948. She showed up at her trial with her long, silver hair tied back with a black bow and the color of her clothes accented by a bouquet of bright red roses, as if at a Hollywood movie premiere rather than a criminal arraignment for treason.

But who was she, really? Born Mildred Elizabeth Sisk on November 29, 1900, in Portland, Maine, at the age of seven, her last name became Gillars when her mother remarried in 1908. Both her father and stepfather were practicing alcoholics and may or may not have abused her as a child. Her half-sister idolized her, recalling decades later that people on the streets stopped and gaped at Mildred’s beauty.

Leaving Wesleyan for an Acting Career in Greenwich Village

At Ohio Wesleyan University, where she was known as Millie, Gillars studied drama, played all the available female dramatic leads in its plays, and excelled at oratory. A known flirt with no female friends and who boasted a fur coat in 1919, Gillars mimicked the stage actress Theda Bara. During her senior year in college in 1922, she suddenly moved, without having graduated, to New York’s Greenwich Village to pursue acting and afterward tour with road show stock companies.

She also performed as a chorus girl in 1926 Broadway musicals, performed in both comedies and vaudeville, and dyed her hair platinum blonde. In 1933, she

and a lover departed for Algiers in North Africa where she studied French. She traveled back and forth between France and America several times, eventually becoming an artist’s model in Paris.

In September 1934, Gillars and her mother traveled to Germany, where Gillars worked as an instructor of English at Berlin’s Berlitz Language School. During this time, she learned German. She took time in 1936 to attend the Summer Olympics in Berlin.

After her mother returned home to America in 1939, Gillars never saw her again. To earn her way, Gillars served as a personal assistant to actress Brigitte Horney, translated German titles into English for the Universum Film AG movie studio, and ghost wrote reviews of German movies in Variety and the New York Times.

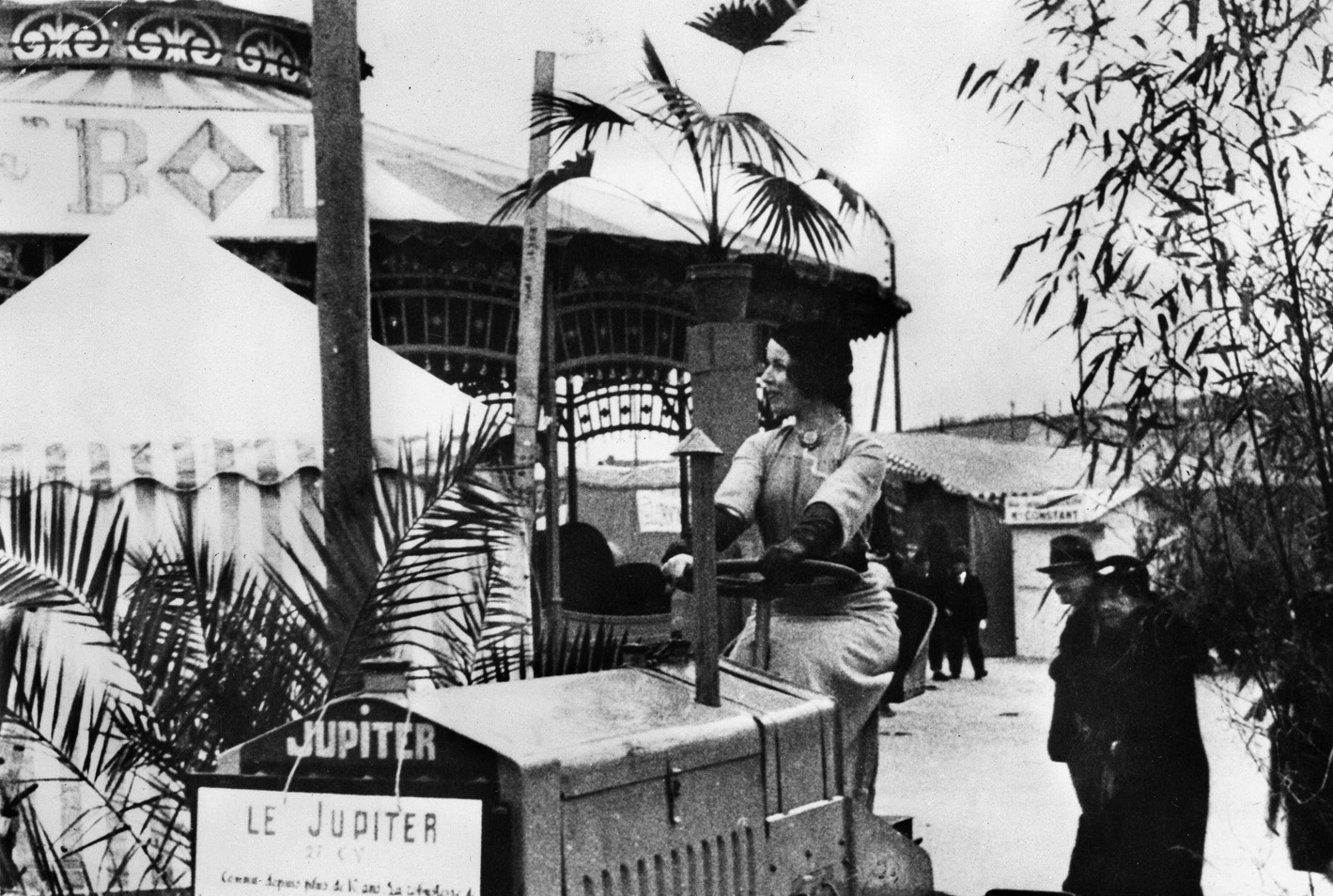

On May 6, 1940, Mildred was hired as an American announcer on Reichs-RundfunkGesellschaft, the German State Radio Network in Berlin, introducing various entertainment programs, displaying an inborn, natural talent for live broadcasting. For nearly five years, the new radio personality became the highest paid announcer on the German Foreign Ministry’s Overseas Service. Her German fiancé, Paul Karlson, was killed in action on the Eastern Front in 1941.

After Pearl Harbor, Gillars castigated off-air the Third Reich’s ally Japan, jeopardizing both her job and her freedom from incarceration in a concentration camp, as she was investigated by the Gestapo. It was at that point that she took the oath of loyalty to Hitler and thus was allowed to continue on-air, doing record announcements and chatty shows as an American national disc jockey.

At her U.S. postwar trial, she steadfastly maintained that she was always a patriotic American: “My war was with England and the Jews,” she said, denying that she had ever wanted America to lose the war.

No Bore On the Stand

Her next lover was a married man, Max Otto Koischwitz. He allegedly became her mentor, writing shows for her to perform live as an actress on-air that the U.S. Justice Department regarded as blatantly seditious. “I loved him, and was willing to die for him,” she said at her trial. Gillars might be considered a mixture of several types, including an overly emotional drama queen, a hysterical would-be actress, and a “stupid woman who sold out,” to borrow the words of a U.S. prosecutor. But she was not boring on the stand. The most tedious part of the trial for the jurors was listening to excerpts of her radio programs.

When Koischwitz suddenly died in August 1944 of tuberculosis and heart disease, Gillars at last began to fully realize the postwar political and criminal implications that her wartime activities would have for her: both imprisonment and even possible execution in the electric chair.

Remarkably, Gillars survived the brutal Battle of Berlin from April 16 to May 2, 1945, but remained silent until her death as to possibly being raped by Red Army soldiers. However, there was a strong sexual component to her prosecutorial character defamation at her Washington treason trial when one U.S. soldier testified that during her interview of him in 1944 she exhibited lewd behavior. As with her married affair with a German propagandist whose wife was undergoing her fourth pregnancy, this went against her reputation at trial.

D.C. On the witness stand, she stood by everything she did while employed in the service of the Nazi propaganda machine.

Gillars was arrested in Berlin on March 15, 1946, and kept in Germany until August 1948, without being charged or given legal representation until flown home for indictment and trial. Her captors even allowed her leave outside detention for Christmas 1946. Indicted by the U.S. Justice Department after being turned over to the FBI by U.S. Army Military Police upon her landing in U.S. territory, Gillars’ heavily reported 102-day trial began in Washington, D.C., on January 25, 1949. The trial included a particularly dramatic fainting spell, as well as a request for sick leave from the courtroom, which was approved.

While she was in jail, noted newspaper columnist Walter Winchell asserted on February 7, 1949, that in fairness to her, Sally’s wartime views might have gotten her elected to the U.S. Congress in prewar America, even as her 1944 radio predictions started coming true. For example, the Truman-era Marshall Plan was enacted to thwart the takeover of all of Europe by Stalin.

“That Woman Right There! She Threatened Us!”

The most dramatic moment of her trial came when she was confronted by one of the former POWs she had interviewed, Gunnar Dragsholt. On the witness stand he yelled and pointed his finger at her saying, “She threatened us as she left—that American citizen! That woman right there! She threatened us!”

“We called her a traitor and shouted names at her as she left the camp,” said another eyewitness, adding, “She shouted vile names right back at us!” She despised the GIs for an incident in which one of them gave her a carton of cigarettes that turned out to be packed with horse manure instead. Another witness disparaged her self-alleged sex appeal, asserting that her jet black hair “had been colored with axle grease, she was heavily rouged, with a low-cut neckline.”

On the witness stand, Gillars stood by everything she did. She insisted that she was a paid performer and not a traitor. But a jury convicted her and sentenced her to 10 to 30 years in prison, as well as a fine of $ 10,000. A Federal appeals court in 1950 upheld the conviction, and the next stage of her eventful saga duly unfolded.

Sent to the Federal Reformatory for Women at Alderson, West Virginia, Gillars quickly settled into prison life again, but because of her superior airs she was generally disliked by her fellow inmates. She kept to herself for the most part and read alone at night in her locked domicile. By 1953, though, her tough exterior began mellowing a bit, and she began participating in activities, such as directing the Protestant choir in 1957. She then began serving others by participating in religious services in jail. She converted from her native Episcopalian faith to Catholicism, receiving the sacraments of both baptism and confirmation in 1960. In addition, she selected the music for mass, coached choir singers, and worked in the garden outside her barracks.

Assigned to the facility’s craft room, Gillars in time became both an accomplished weaver and competent seamstress. As her room began filling up with her various completed projects, it even garnered the admiration of her guards. Placed in charge of the ceramics kiln, Gillars made exceptional blue Bavarian beer steins that featured the self-revelatory inscription, “Accept your fate, for it is sealed.”

Her co-prisoner and fellow enemy radio announcer Iva Toguri D’Aquino, who was nicknamed Tokyo Rose, applied for and was granted a presidential pardon, being freed in January 1956. In contrast, Gillars never asked for nor received a pardon. When she became eligible for a normal parole at age 58 in March 1959, Mildred failed to apply because she did not want to be freed, fearing both physical harm in the United States and also possible deportation to the new Federal Republic of Germany. Besides, she reasoned, without a job or any money, she had nowhere else to go.

On Parole & Religious Conversion

This situation changed for the better, though, after her religious conversion, when the Our Lady of Bethlehem Convent in Columbus, Ohio, offered her a job teaching music to novice nuns at the nearby St. Joseph Academy upon her release. In return, she would be given free room and board, living in the convent itself, and $30 a month in pay.

The parole board approved her release on January 12, 1961, with the stipulation that she report to her parole officer every two weeks into 1979, for another 18 years of supervision, to which she complied. Upon her release on July 10, 1961, the former notorious Axis Sally began yet another remarkable stage of her most unusual journey through life. Once more, there were press and popping camera flashbulbs for what was to be her last grand appearance on the stage of notoriety. She gave her last press conference in her stepsister’s yard at age 60. “It was painful, but she pulled it off,” said one observer.

Over time, she also taught the novice nuns French and German, piano, drama, and chorale music, being granted salary increases of as much as $100 a month. She also gave piano lessons on Saturdays to inner-city children. Noted biographer Richard Lucas wrote of this segment in her ongoing journey to redemption, “In her final role, she was respected, needed, valued, [and] even beloved.”

During the two world wars she had sought fortune but found infamy instead, and she managed to reverse her life’s trajectory in the four decades after World War II by shunning almost all publicity. There were two minor exceptions, though. In 1967 at age 66, Mildred granted an interview request to surprised local cub newspaper reporter Helene Anne Spicer, who found her to be, “A sweet, little old lady—nothing like I expected.” Her second and last post-prison brush with fame occurred at age 72 on June 10, 1973, when she was duly awarded her college diploma after a hiatus of 51 years from her former alma mater, Ohio Wesleyan University.

When religious vocations dwindled down to but 11 sisters-designate in 1968, Mildred’s restoration appeared to be coming to a close until her probation officer located her original birth certificate in Maine, allowing her to apply for and be granted both Social Security payments and Medicare. On her own for the first time since her arrest in 1946, at age 74 the selfreliant Gillars ended convent living after 13 years, moved into her own apartment once more, and underwent laser eye surgery for a detached retina. To earn extra money, Gillars tutored students at a nearby high school where her new superiors credited her teaching with raising former D grades to A status. One observer was amazed that she did crossword puzzles in German.

A Good & Simple Life In The End?

Surrounded by books and art in her small home, she refused all further interviews, ending her 30 years of supervision in 1979, her past largely unknown to her students, friends, and neighbors. Diagnosed with metastatic colon cancer, she died at age 87 on June 25, 1988, without any public funeral, but with friends present at her burial in a still unmarked grave at Lockbourne, Ohio.

Impoverished most of her life, Mildred was a hospital charity case, with her estate being valued at but $ 3,194.16, which was divided up for her medical needs, healthcare, and other expenses. Her neighbors were shocked to learn of her previous fame when her demise was covered by the New York Times, Washington Post, and the national news wire services. One friend proclaimed her “brilliant,” while another observer declared that she had lived a good and simple life at the end.

In 1945, Gillars was alone, broke, and unmarried. She was a woman without a country who was about to go on trial for her life. Having lived through it all without repentance, she had survived and died having outlived her own treasonous past. The notorious Nazi propagandist had repented at last.

Very interesting life Mildred led. I just saw American Traitor, and was fascinated with her. So, her “war was with the English and the Jews.” An ambitious antisemite. That does sound like a Nazi. נאצו מפלצת

Very interesting movie of Axis Sally! Love is indeed blind… I think she got caught in the mess and brainwashed. Looking at the old pictures, I am amazed at how fit and lean Americans WERE as compared to today!

James J. Laughlin was my grandfather, mine and my 5 siblings. We still miss him terribly. I just wanted to chime in and say that “JJ”, as we called him, was nothing like how Al Pacino portrayed him, and we are furious about this inaccurate representation. No one involved with this movie contacted any of us. “JJ” was 6’2″ (almost an entire foot taller than Al) and always immaculately dressed. He did not drive, at all. He spoke proper English and used his manners, always. He also did not have a picture on his desk of an imaginary, deceased relative that served in the war, because there wasn’t one. We agree, this movie is horrific, and mostly because Meadow Williams stole the family fortune of her recently deceased, senior husband and paid $3 million dollars to get this part. We are proud of our grandfather and grateful that at least at the end of the movie, they show a real picture of our “JJ” – even though they couldn’t be bothered to even have his name with his picture.