By Kevin M. Hymel

George Washington looked down at the surrender documents. They were soaked from pouring rain and the ink was splotched. Washington’s forces were surrounded and a third of his men were sick or wounded and unable to take up arms. Resigned to his helpless plight, he signed the documents. What Washington did not realize was that, by signing the document, he was admitting to an assassination.

Fortunately for Washington and the cause he would come to represent, this was not the American Revolution—it was 1754. The British and French were competing for domination of the area north of the Ohio River between French-controlled Canada and the British-controlled colonies along the East Coast. The two countries were not in a shooting war, but in a cold war of expansion that constantly threatened to get hot on a global scale. With colonies in Africa, Asia, and the New World, the two world powers were bound to collide somewhere.

Young Lt. Col. George Washington

Along with Canada, the French controlled lands in the West and as far south as Mexico. They were using the Ohio Valley’s rivers to connect their possessions, hem in the British colonies, and eventually push the British off the continent altogether. By 1749, the French had sent troops into the Ohio Valley to build strategic forts along its rivers. As French influence grew, the British became increasingly worried. They wanted the Ohio Valley for themselves. An editorial in a Boston newspaper declared that if the British did nothing to stop this encroachment, the French would eventually “lay a solid and lasting foundation for making themselves Masters of America.” When stories of French atrocities reached Virginia in January 1754, Governor Robert Dinwiddie sent a small force under the command of Captain William Trent north to build a fort at the fork of the Ohio River, near present-day Pittsburgh. The Virginians had barely begun construction when French soldiers forced them out of the area and began building their own fortification, Fort Duquesne.

Dinwiddie immediately upped the ante. Concerned about British settlements—and his investments in the Ohio Company that facilitated those settlements—he decided to send another force of Virginians marching north. At the head of this force he placed 22-year-old George Washington, a lieutenant colonel in the Virginia militia who had never before seen combat. Dressed in a red British officer’s uniform with white lace cuffs, riding breeches, black boots, a tri-cornered hat, and with a silver gorget around his neck, Washington stood an impressive six feet, two inches tall. The only military training he had received came from his constant reading of military texts. He was, however, familiar with the Ohio Valley—he had helped survey the area when he was 18. In addition, he had traveled to the area the previous November to deliver a letter from Dinwiddie to French officers on the north bank of the Allegheny River. The letter ordered the French to evacuate the area. They refused, but invited the young courier to dine with them. Over dinner, the French officers drunkenly boasted to Washington that they intended to take the entire Ohio Valley.

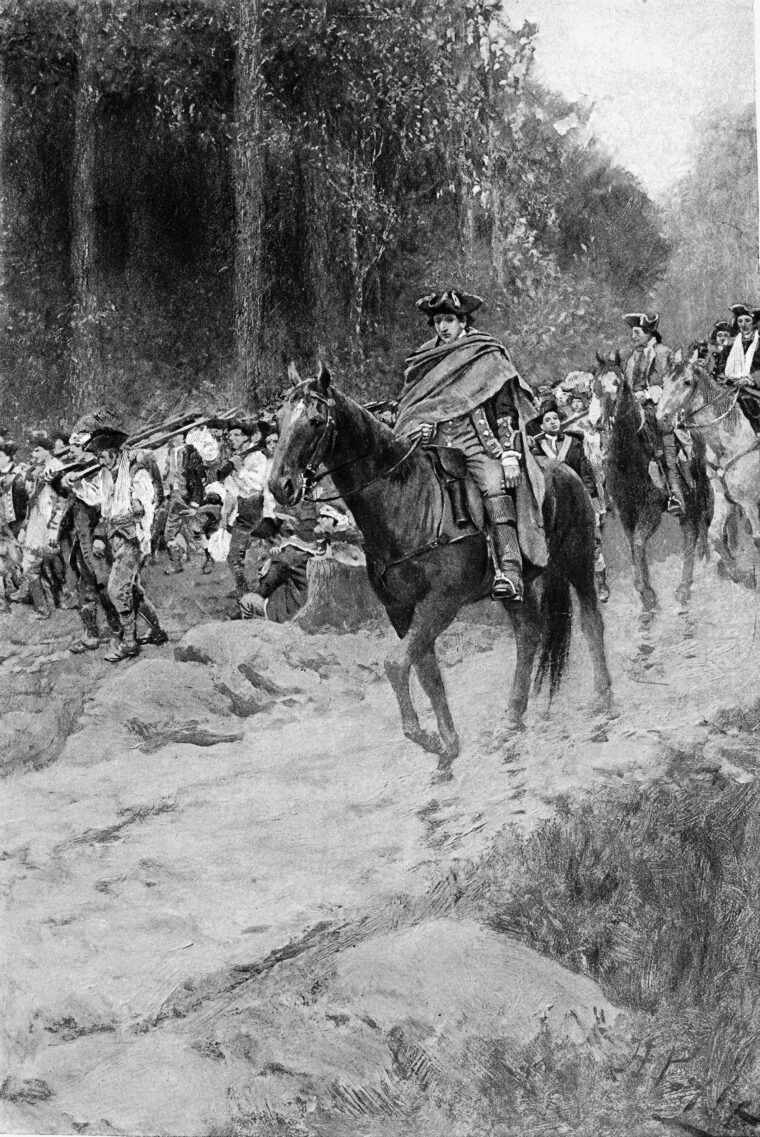

On April 2, Washington started off from Alexandria, Virginia, with over 130 men. His mission was to build forts and roads until reinforced by Colonel Joshua Fry, who would join him, take command, and complete the work. The troops mostly wore a red regimental uniform with gray stockings and black, tri-cornered hats, but many were clad in hunting shirts and a combination of uniform and civilian clothes. They were armed with muskets, but only a few had bayonets. The recruits, candidly described by Washington as “loose, Idle Persons, that are quite destitute in House, and Home,” had been promised an equal share of 200,000 acres of land in the Trans-Allegheny for their trouble.

The journey north was arduous. At one point, the column was able to traverse only 20 miles in 15 days. On April 20, when he reached Wills Creek, Washington learned that Trent had been forced from the area by the French and that the fort Trent’s men were supposed to be building had been replaced by Fort Duquesne. Washington decided to push on alone.

“A Charming Field for an Encounter”

On May 24, the Virginians reached the Great Meadows, which Washington called “a charming field for an encounter.” The well-known meeting site, 50 miles north of Wills Creek, was flat and open, nestled between two ridges. Two small streams connected in the meadow, providing ample drinking water for his men. Washington decided to make camp and await developments.

Four days later, Washington received word from Mingo Indian chief Tanaghrisson, also known as Half-King, that a French spying party was concealed just west of the Virginians. Reacting quickly, Washington gathered 40 men and led them west along a narrow trail. After hiking three miles in pitch-black darkness and pouring rain, he met up with Half-King, who showed him the French camp. Washington conferred with the Indian and decided to attack.

The French were encamped at the bottom of a ravine. The group of 33 men was preparing breakfast and had not mounted a guard—some were not even dressed. Their arms were either stacked or leaning against rocks. Utilizing the high ground, Washington had his men and the Indian reinforcements encircle the camp. Whoever fired the first shot, French or English, is disputed, but the results are not. It was a slaughter. Washington’s men fired a volley. The French, according to Washington, “ran to their arms and fir’d briskly.” But they were surrounded and caught off guard, and could not react quickly enough. Washington’s men fired another volley and the battle was over. Ten Frenchmen had been killed, one wounded and one escaped. Twenty-one others were captured.

The skirmish had lasted only 15 minutes. After the two volleys from Washington’s men, the French threw down their weapons and ran to the rear, but upon encountering the Indians, turned around and rushed toward the Virginians. The wounded French commander, Joseph Coulon de Villiers, the Sieur of Jumonville, called to Washington and showed him his orders, which said he was on a mission of surveillance, not engagement. As the letter was being translated, Half-King ran up to Jumonville and said in French, “You are not dead yet, my father.” He then raised his tomahawk and brought it down hard, splitting open Jumonville’s skull. He then reached into the gaping wound, scooped out a handful of Jumonville’s brain, and scalped him. As if on cue, the other Indians began killing the wounded Frenchmen and brandishing their blades to peel the scalps off the dead.

Jumonville Glen

Washington, whose first military action had been a surprising a success, was completely taken aback by the Indians’ war practices. He knew all about scalping—it was a common practice among some whites as well as the Indians—but he had never seen it take place so close. Still green to combat, Washington realized that the formal European military actions he had read about bore little resemblance to the backwoods fighting of the American wilderness. European armies fought like chess pieces moving around a board, with plenty of maneuvering, but this kind of combat was chaotic and savage. Any romantic dreams of glory Washington may have harbored vanished with the brutal death of Jumonville.

Washington had another concern: Had he just conducted an act of war? Jumonville’s letter, which simply declared that the British should leave the area, had a marked similarity to the letter he had delivered to the French six months earlier, when he was on a mission of peace. The letter was received, but the messengers were now dead and scalped, except for the one Frenchman who was now making his way back to Fort Duquesne to report the atrocity.

Despite the confusion, Washington had survived his baptism of fire at what would become known as Jumonville Glen. He had stood exposed to fire while French shots sailed past him, yet kept his cool. He later wrote of the experience, “I heard the bullets whistle, and, believe me, there is something charming in the sound.” He gathered his men, the prisoners, and their equipment and headed back to the Great Meadows. He realized, however imperfectly, that he had stirred up a hornet’s nest. The French would retaliate once the lone survivor informed his superiors of the massacre.

On the Offensive

Back at camp, Washington put his men to work constructing a fort in the meadow. Meanwhile, he sent his prisoners south to Virginia under a small guard. The rest of the men began splitting timbers and sinking them into the ground, making a circular wall with pointed tips. Inside, they built a small wooden storehouse, covered with bark and animal skins, to keep dry the powder, supplies, and the barrels of rum. Major Robert Stobo named the fortification Fort Necessity, “in honor of our empty bellies.” Around the base of the fort, the men dug rifle pits.

While the fort took shape, Washington learned that reinforcements from Alexandria would not be reaching him immediately. He also got word on June 6 that Colonel Fry, who was supposed to replace him as commander, had died in a horse-riding accident, making Washington the highest ranking officer in the area. He was cheered when reinforcements reached his camp on June 9, bolstering his numbers to almost 300 men and nine swivel guns—small cannons capable of firing solid or grapeshot from 100 to 200 yards. Five days later a company of North Carolina soldiers, 100 in all, marched into camp. A problem ensued, however, when their commander, Captain James Mackay, told Washington that since his commission came directly from the Crown, he would take command. Washington politely refused the order, explaining that there was no difference between militia and army rank. Mackay’s men made a separate camp within Fort Necessity and refused to salute Washington’s men.

Instead of staying at Necessity and improving its defenses, Washington decided to take the offensive. He led his Virginians northwest to Gist’s Mill, leaving Mackay at the fort. Gist’s Mill was the first English settlement west of the Allegheny River. The 20-mile trek was arduous. As wagons broke down and horses died at an alarming rate, the men were forced to carry their supplies on their backs, including the heavy swivel guns. The journey took two weeks, and when Washington’s men reached the small plantation, they found it swarming with Indians who had been sent to spy on the Virginians. The French were expecting them.

Washington tried to convince the Indians to join his men and Half-King against the French, but it was useless. The Indians were more concerned with which side had the most men—and it was not Washington’s. He set to work laying yet another road and building defenses around the mill. But when Washington learned that a force of 800 French and Canadians and 400 Indians was advancing, he called for Mackay to join him. Somewhat surprisingly, Mackay did so promptly.

The Return to Fort Necessity

Washington’s position was precarious. His defenses were weak, and two of his soldiers had deserted and were probably telling the French about his lack of food as well as the small size of his force. Half-King and his Mingos threatened to abandon Washington if he did not retreat to the better defenses of Fort Necessity. Washington realized that a trek back over the mountain roads put him at risk of an ambush, but he agreed with Half-King that returning to Fort Necessity represented their best chance for survival. He decided “to decamp directly, and to have our swivels drawn by the men by reason of the scarcity of horses.”

The journey back was worse than the trek to the mill. Washington’s men had not eaten bread in six days, and none was forthcoming. The only food they had was some dried corn and a little salt. The cows were in worse shape than the men. Even worse, Mackay’s men, explaining again that they were the King’s soldiers, refused to carry either equipment or weapons, which did not go over well with the Virginians. Washington tried to set a good example by loading his own horse with equipment and even paying $16 to the men who helped him with the work.

After a tough, two-day trek over what one soldier called the “roughest and most hilly Road of any on the Alleghany Mountains,” Washington’s men arrived back at Fort Necessity. What they found was not encouraging. The expected reinforcements had not arrived, and the stores of food they hoped to find turned out to be a few bags of flour.

Villiers Seeks Vengeance

There was no time to rest. Washington’s men began shoring up Fort Necessity’s defenses—even Mackay’s men contributed to the work this time. The trenches took the form of a diamond surrounding the fort. Those not working on the rifle pits cut back parts of the forest, dug a trench to the small creek and built platforms from which to fire the swivel guns. Unfortunately, the defenses would not be ready before the French arrived. Washington admitted that he “had not the Time to perfect” the fortifications. Still, with no experience in fort building or siege tactics, Washington nevertheless thought Fort Necessity was capable of withstanding an attack from 500 men.

Unknown to Washington, the day after he had set off for Fort Necessity, the French had broken camp with a force of 600 French and Canadian soldiers, bolstered by some 100 Indians. It was smaller than had been reported to Washington, but still much larger than his 400 sick and starving men. Leading the French force was Captain Louis Coulon de Villiers, the older, half brother of the murdered Jumonville. Villiers’s quest for revenge was encouraged by his superiors, who ordered him to “avenge ourselves and chastise them for having violated the most sacred laws of civilized nations.”

Back at Fort Necessity, Washington’s Indian allies began to worry about their plight. Those sent to reconnoiter the front became alarmed by the huge number of rival Indians in the woods, preparing to do battle. Half-King encouraged Washington to retreat farther south to Wills Creek , but this time Washington refused—his men were in too wretched a condition for any more forced marching. Frustrated by the young officer’s refusal to listen to his advice and not wanting to be on the losing side of a battle—and possibly lose his own scalp—Half-King led his Indians out of camp.

Around 9 o’clock on the morning of July 3, Washington got word that the French were approaching. Preparations quickened as men began loading their muskets and swivel guns. Washington’s greatest fear was that the French would charge his entrenchments, because the French were armed with more bayonets than his men. He could only muster 300 men healthy enough to fight against some 700 of the enemy. Fully one-fourth of his men were too sick or exhausted to fight.

A sniping Battle

All was silent in the surrounding forests as Washington’s men rushed to finish their entrenchments. Then, around 11 am, a lone sentry fired his musket into the woods. The battle was on. The French, shouting and cursing, emerged from the woods. Washington sent his men out to form ranks. The French opened fire, then turned and retreated to the woods. Washington wisely held his fire. The enemies’ shots, from roughly 600 yards away, were ineffective. Washington quickly realized that the French were not fighting by European rules. They had no intention of charging across open ground; they were content to keep to the woods. Washington ordered his men back to the trenches and gave the order to fire. His men opened up with muskets and swivel guns. Their fire, according to their commander, “was done with great Alacrity and Undauntedness.”

The French continued to maneuver in the woods, looking for an area closer to the fort from which to attack. They found such a place 60 yards away and began firing. The Indians then attacked. Again, Washington gave the order to fire and his men let loose another volley, stopping the Indians cold.

The fighting degenerated into sniping by both sides. To the men inside the trenches, the fire seemed to be coming from every tree, stump, stone, and bush along the wood line. The French, dressed in blue uniforms with green leggings, were hard to spot, as were the Canadian militiamen, clad in animal skins. The Indians, despite their war paint, blended into the landscape with their dark clothes and tan bodies. Washington’s men returned fire as best they could, using grapeshot from the swivel guns. One company remained within the stockade, firing though slits in the palisades. The French surrounded the fort and concentrated their shots on anyone who rose above the battlements to return fire. Casualties mounted. Men were getting killed or wounded from both direct fire and balls ricocheting off the wooden palisade. Jagged wooden splinters exploded from the walls, adding to the injuries. Washington’s personal slave was counted among the casualties.

The French opened fire on Washington’s cattle and horses as well, killing most of the animals. It was another blow to the men’s morale. Even if they outlasted the French fire, they had nothing but a little flour to sustain them. The firing continued late into the afternoon, until storm clouds rolled in and the skies opened up with a downpour. Washington remembered it as “the most tremendous rain that can be conceived.” Trenches filled with water and rain soaked the ammunition and firelocks. There were only two screws for the whole regiment to clear the wet charges in their muskets. Slowly, the fire from Fort Necessity began to slacken. To make matters worse, the hard-pressed defenders broke into the rum, and soon half the regiment was thoroughly drunk.

“Voulez-Vous Parler”

That night, a single French voice broke the tension-filled silence. “Voulez-vous parler [Would you like to talk]?” Washington refused to respond, assuming the request was a ruse to get him to leave the safety of the trenches for the no-man’s-land between the fort and the forest. The request was repeated, and Washington eventually decided that the request was a legitimate attempt to open negotiations. He sent two of his men into the middle ground, where they met with a French delegation.

The men returned with two copies of a surrender document, both in French. One of the men, Jacob Van Braam, was Dutch but spoke French. He brought the documents to Washington and Mackay. The documents were in terrible condition, water-soaked and smeared with mud. Huddled over the documents in the leaky storehouse, Washington and Mackay listened as Van Braam laboriously tried to translate over candlelight.

Villiers’s conditions were generous, considering the circumstances. They allowed Washington and his men to leave the valley in peace with any belongings they could carry with them. Their heavy guns and muskets, however, would have to be surrendered—except for one swivel gun. They would be granted full military honors as they left, but the English flag would have to come down and French troops would occupy the fort once it was vacated. Since the Virginians had no way to carry all their baggage, they could leave it under guard until they retrieved it later. In addition, two of Washington’s captains would have to remain as hostages until the prisoners Washington had captured at Jumonville Glen could be returned to Fort Duquesne.

Washington returned the documents to the French with a request that they strike the line about his men surrendering their muskets. He would be retreating several hundred miles through hostile forests, and his men needed their weapons and ammunition for self-defense. Upon receiving Washington’s response, Villiers easily ran a line through the sentence. He may have been surprised that Washington did not dispute an earlier line in the treaty. In the second line of the text, Villiers had written that the objective of his force had been “only to revenge assassination which had been done to one of our officers.” Basically, he was calling Washington a murderer.

Why Van Braam did not question the word is unknown. He may not have been familiar with the word or its English translation. He also may not been able to read the word on the rain-soaked document. Weeks later, when a clerk translated it into English in Williamsburg, he translated the word “assassination” as “assault,” then crossed it out and replaced it with “killing.” Nonetheless, when the document came back, Washington and Mackay had both signed it. Since Mackay had not been with Washington at the ravine, it was only Washington who was admitting, albeit unknowingly, to the assassination of Jumonville.

Spoils of War

The next day, July 4—ironically enough—the French emerged from the woods following a beating drummer. They formed two columns outside Fort Necessity’s gate and awaited the surrender. The troops, led by Washington, filed out of the fort and assembled in the open field. The men were soaked with mud, their faces still besmirched with powder from their muskets. The officers looked as badly spent as the enlisted men; many were missing parts of their uniforms.

The Frenchmen’s Indian allies went for the stacked baggage and anything else they could grab. One Indian rounded up 10 of Washington’s men and brought them to Villiers as a gift. He promptly returned them. With the Indians so eager to claim the spoils of war, Washington’s men set fire to the remaining baggage. The French began destroying the remaining swivel guns, including the one Washington had been promised. It was too heavy to transport, anyway. Villiers, worried about the unruly behavior of his Indian allies, had all the liquor casks within the fort destroyed.

The Indians were not the only ones searching for souvenirs from the battlefield. As Major Adam Stephen was forming his men, his servant called his attention to a French soldier making off with his saddlebags. Stephen, furious at this breach in the surrender agreement, chased down the man and kicked him in the rear. The French officers, surprised by Stephen’s brusque manner, asked if he was an officer. When he told them he was, they were doubly surprised since Stephen looked just as disheveled as his men. To prove his point, Stephen pulled his bright red regimental jacket out of his saddlebag and put it on. The French officers relaxed and joked with Stephen that since the British had already given them two hostages, they would like to become hostages themselves. They wanted to find out if the stories of the Virginia belles were true.

A Cool Reception

The one-day action exacted a heavy toll on Washington’s command. He had lost 30 men killed and 70 wounded. By contrast, Villiers had lost only two Frenchmen and one Indian killed and 17 wounded. Washington and his men stayed the night and began marching home the next morning, carrying the wounded on their backs. The French put a torch to Fort Necessity before departing. The paltry symbol of British strength in the Ohio Valley, George Washington’s first command post, burned to the ground.

Upon his return to Virginia, Washington received a cool reception from Dinwiddie. The governor now considered his young officer a liability. In a letter to the Crown, Dinwiddie explained that “my orders to the commanding officer were by no means to attack the enemy till all the forces were joined.” Dinwiddie hinted that things might have gone better if he had led the expedition. The governor, however, had no more military experience than Washington and had no appreciation at all for conditions in the field. After criticizing Washington’s performance, Dinwiddie turned around and ordered Washington north again. But the order came to naught. The men of the Virginia militia were half-starved, unpaid, and practically naked after their recent excursion. Washington suggested that only a death penalty for desertion would keep his men in camp. Dinwiddie, oblivious to the men’s condition, told Washington airily that any problem with his men came from “the want of proper command.”

Immediate Political Consequences

Washington’s surrender had an immediate effect on relations between the British and the French. His alienation of the Indians caused almost all of them to side with the French. They would now harass any British farmers or traders in the Ohio Valley. Washington also jeopardized Great Britain’s moral claim to the New World by formally admitting to the assassination of a French officer. The French, who captured Washington’s journal, had it translated and printed in pamphlets that they distributed throughout Europe, claiming that the British had violently disrupted their peaceful occupation of the Ohio Valley and that George Washington was a self-confessed murderer.

Great Britain and France would remain at an uncomfortable peace until Great Britain officially declared war on May 15, 1756, launching the French and Indian War, which was part of the larger Seven Years’ War. It was the first European war to commence in territories outside of Europe. All previous wars had begun in Europe and then moved into the territories. The end of the war found Great Britain in control of North America as far west as the Mississippi. But the war was costly, and when it ended in 1763, Great Britain turned to its colonies to pay its war debt, indirectly sowing the seeds for the American Revolution just over a decade later. In a way, the brief exchange of fire in Jumonville Glen eventually led to a world war that forced the French out of North America, which was followed by another war that forced out the British. Horace Walpole, a British politician, may have summed it up best when he wrote, “The volley fired by a young Virginian in the backwoods of America set the world on fire.”

The Fate of Fort Necessity

Washington would eventually return to the Ohio Valley and to the site of Fort Necessity at least three times. When Great Britain decided to retaliate for the black eye suffered at Fort Necessity, it sent a force of 2,400 recoats to Pennsylvania to retake the valley under the command of veteran Maj. Gen. Edward Braddock. Washington, as Braddock’s aide-de-camp, passed by his old “charming field” and may have eyed the burnt timbers of the old fort, but there is no record of his visiting the battle site.

Braddock’s mission would prove to be a repeat of Washington’s disaster the year before. Closing in on Fort Duquesne, Braddock chose to employ his men in the back-breaking effort to cut a road through the wilderness instead of sending out scouts and flankers to keep tabs on the French. When the enemy struck him head on, he pushed back, but the French and Canadians took to the woods and wreaked havoc on Braddock’s flanks. Repeating Washington’s mistake, Braddock concentrated his men on the road out in the open, where the French and Indians, once again under cover in the woods, took easy aim at the clusters of red-clad troops.

Washington spent the battle trying to re-form the lines. Two horses were shot from beneath him. A sniper’s bullet caught Braddock in the back, fatally wounding him. After the retreat, Washington ordered Braddock’s body buried in the center of the road close to Jumonville Glen. The men then marched over the mound to hide it from curious Indians. Washington hoped to rebury it later, but Braddock’s body was never found.

Washington revisited the area twice after that, once in 1770 and again in 1784. On the first trip, he purchased the land where Fort Necessity once stood. On the second trip, well after the American Revolution, he tried to lease the land, but he never found anyone interested in the deal. In 1811, the acreage of Fort Necessity became part of the National Highway, the first federal highway built in the United States. It roughly followed Washington’s and Braddock’s route, which had been an Indian trail, “Nemacolin’s Path.” It made the area more accessible to people heading west into Ohio and Illinois, just as the British had intended in 1754.

Pivotal Lessons from Defeat

The exchange of fire at the ravine and at Fort Necessity was more than a mere border skirmish— it was a learning ground for the young lieutenant colonel. Washington made some amateur’s mistakes in his first engagement. He rashly attacked the French; he pushed his men too hard, exhausting them before a major engagement; he left his fort before its defenses were completed; and he allowed an enemy to surround him. He also treated his Indian friends poorly, ignoring Half-King’s advice on strategy.

Washington did, however, learn many lessons from his first combat that would serve him well in the American Revolution. During that war, he would never let himself get surrounded again—he would always keep open an escape route. He also learned that men in battle had their limits and that an army on the move had the advantage over one that was stationary. Most important, he learned to be magnanimous in victory, because he had personally experienced the bitterness of defeat.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments