By. Roy Morris, Jr.

Never was Theodore Roosevelt’s famous dictum, “Speak softly and carry a big stick,” used to greater effect than in the high-stakes standoff between the American president and prickly, pugnacious Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany over the debt crisis in Venezuela in December 1902.

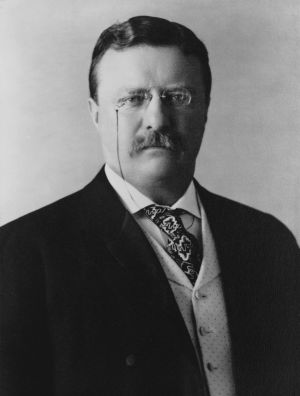

Roosevelt and Wilhelm, superficially at least, were much alike. Born within three months of each other, they were both athletic, competitive, and high-strung. Both had overcome debilitating childhood ailments—Roosevelt suffered from severe asthma; Wilhelm was born with a withered left arm—by sheer force of will, and had risen to lead their nations. Both men, too, were avid readers, particularly of military history, and shared a healthy respect for the use of sea power in national affairs.

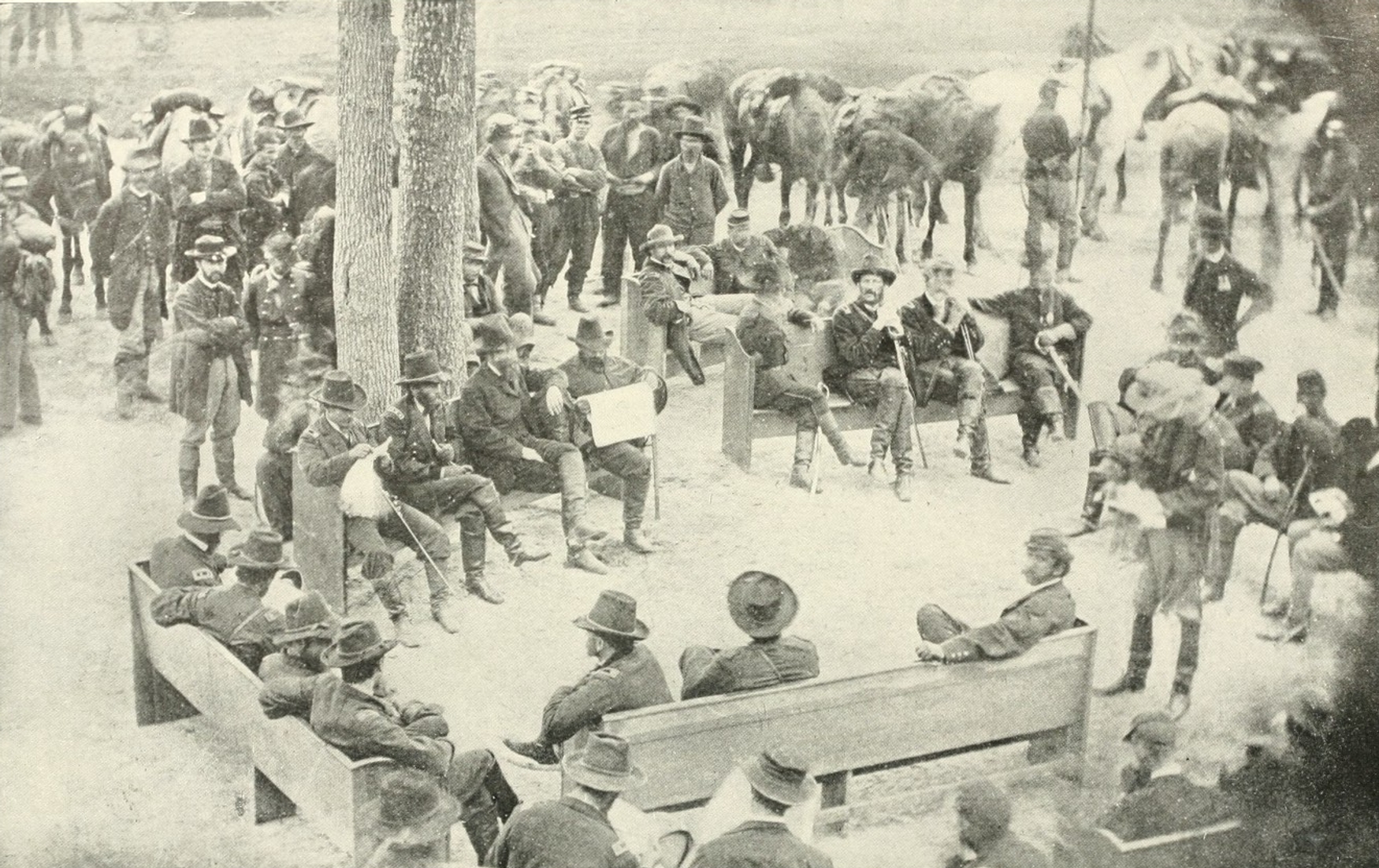

But there were significant differences between Roosevelt and the Kaiser, as well. Roosevelt was a prototypical extrovert, a man who, it was said, “wanted to be the bride at every wedding and the corpse at every funeral.” His toothy smile was world-famous. Wilhelm was a great deal more reserved. Most importantly, Roosevelt had actually fought in a war, charging up Kettle Hill in the Spanish-American War at the head of his Rough Riders and winning a (long-delayed) Medal of Honor in the process. Wilhelm’s military service amounted to riding in parades and sporting a largely self-awarded rack of medals on the breast of one of his 300 different uniforms.

But there were significant differences between Roosevelt and the Kaiser, as well. Roosevelt was a prototypical extrovert, a man who, it was said, “wanted to be the bride at every wedding and the corpse at every funeral.” His toothy smile was world-famous. Wilhelm was a great deal more reserved. Most importantly, Roosevelt had actually fought in a war, charging up Kettle Hill in the Spanish-American War at the head of his Rough Riders and winning a (long-delayed) Medal of Honor in the process. Wilhelm’s military service amounted to riding in parades and sporting a largely self-awarded rack of medals on the breast of one of his 300 different uniforms.

It was inevitable, perhaps, that two such larger-than-life individuals would clash. The stage of their confrontation was South America, specifically corrupt, debt-ridden Venezuela. When Cipriano Castro, “an unspeakably villainous little monkey,” in Roosevelt’s view, seized power after a revolution in 1899, he repudiated his country’s mountain of debts to European nations, specifically Germany and Great Britain. Three years later, the two powers announced that they were preparing to blockade Venezuela’s ports and demand repayment of their debts.

Roosevelt, who as vice president had stated that “if any South American country misbehaves toward any European country, let the European country spank it,” now let it be known that the United States would look unfavorably upon any European efforts to seize Venezuelan territory as part of its forcible debt recovery.

This was precisely what Roosevelt feared the Kaiser would attempt. He became convinced, Roosevelt said later, “that Germany intended to seize some Venezuelan harbor and turn it into a strongly fortified place with a view to exercising some measure of control of the future Isthmian Canal and over South American affairs generally.” To forestall such an occurrence, the president sent Admiral George Dewey steaming into the Caribbean at the head of a 53-ship armada to monitor affairs.

Having made a public show of strength, Roosevelt privately gave the German ambassador to America, Theodor von Holleben, a personal message for the Kaiser. The United States, he said, would be obliged to meet with force any German efforts to acquire territory in South America. He would give Germany 10 days to issue a public disclaimer of such intentions. As further inducement, Roosevelt advised von Holleben to tell the Kaiser to look at a map. “A glance would show him,” said the president, “that there was no spot in the world where Germany … would be a greater disadvantage than in the Caribbean sea.”

Roosevelt’s deadly serious warning, issued in private, ultimately induced Wilhelm to back down and submit the Venezuelan controversy to international arbitration. More to the point, by not making such threats publicly, the president had allowed the touchy German leader to save face by seeming, on his own, to favor diplomacy over force. The president had gone eye-to-eye with the Kaiser, and the Kaiser had blinked first.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments