By Glenn Barnett

The spring of 1941, particularly the month of May, was a troubled time for Great Britain. The German battleship Bismarck had sunk the huge British battlecruiser Hood in just six minutes and was making a getaway to the coast of German-occupied France. Every British capital ship in the Atlantic stopped what it was doing and gave chase, but the Bismarck had given them all the slip.

On the stormy evening of May 26, with seas running high there was only an hour’s worth of daylight left to stop the German ship. She would very likely outrun her pursuers in the dark and in the morning would be under an umbrella of protective air cover.

Out of Date but Effective

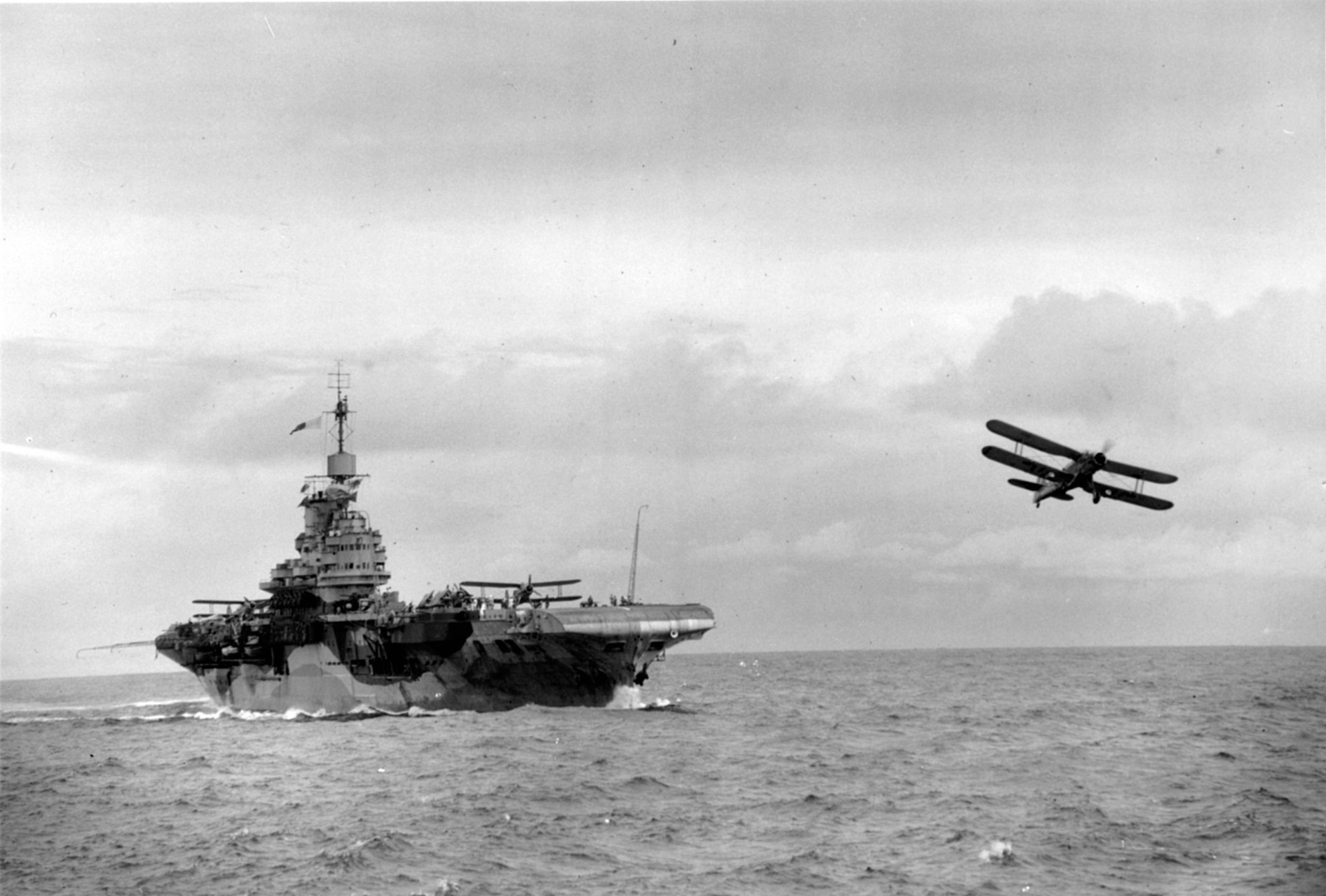

Only the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal was within range of the Bismarck. She turned into the biting wind and slowed to 12 knots to launch her planes. Even at the reduced speed, her flight deck, bow and stern, see-sawed 60 feet with every wave. Off the rain-soaked deck lifted a flight of 15 Fairey Swordfish torpedo planes. They would catch the German battleship in the growing darkness under a gray scud of clouds. Two torpedoes slammed home. One of them just barely hit the ship’s huge rudder, jamming it hard to port. Unable to steer, the Bismarck steamed in impotent circles until British battleships surrounded her by morning and pounded her to death with their big guns.

Had it not been for the Swordfish, the Bismarck would have reached France with a rare German naval and propaganda victory and lived to fight another day. Remarkably, the crippling blow dealt to the most modern of battleships was delivered by an outdated biplane.

By 1940, the era of the biplane was long over. The Swordfish was a relic of the past with her agonizingly slow speed, open cockpit, fixed landing gear, and canvas fabric skin. Yet, her importance during the war rivals that of any other combat aircraft.

Like many weapons systems of the inter-war years, the Swordfish was out of date by the time the prototype rolled off the assembly line in 1933. However, at the height of the worldwide economic depression, naval budgets were tight. This one plane would have to fulfill all combat rolls except that of a fighter. The lumbering biplane was built to carry such a variety of ordnance that an early wag likened it to a popular shopping bag used by English women known as a “string bag.” The nickname stuck.

Originally the brainchild of privately owned Fairey Aviation, the Swordfish was designed to accomplish a number of tasks. She could carry a 1,610-pound torpedo or anti-ship mines, bombs, flares, or depth charges. She could be used in a reconnaissance role on land or sea or as an artillery spotter for naval guns. She could perform convoy escort duty or drop mines into enemy harbors. During the war she was used as a tank killer in North Africa and in clandestine missions inserting and extracting agents from occupied territory. She could fly from land bases or as a floatplane off a ship’s catapult, but her best use was aboard an aircraft carrier.

The Swordfish’s dual wings gave it extraordinary lift on the short carrier decks of that era. The wings folded back when the plane was on deck to maximize storage space. She needed little room to take off or land. The plane’s simple design and reliable 690-horsepower Bristol Pegasus engine made maintenance relatively simple. The plane’s listed stall speed was an unbelievable 50 miles per hour, which was another plus for carrier landings.

As events would prove, she was amazingly sturdy and could absorb the shocks of carrier landings in rough seas and in darkness. She could also take an amazing amount of battle punishment in her canvas frame and wings and still make it home. All 15 planes that flew against the Bismarck returned safely to the Ark Royal, finding the carrier’s deck above the dark and pitching sea. Several were riddled with holes.

The Swordfish’s Strengths and Weaknesses

The Swordfish did have her weaknesses. The seating was cramped, and the cockpit was open to the elements. This made long flights, especially in the frigid North Atlantic and Arctic, a misery for her three-man crew. Her top speed was 130 miles per hour unloaded and 92 miles per hour fully armed. This made her vulnerable to sleek German fighter planes. Yet, even her slow speed was deceptive, for the Swordfish was the most maneuverable plane in the air. She could turn inside any other combat aircraft. An accomplished pilot could turn his Swordfish around within her own 45-foot wingspan.

In a power dive, the Swordfish could pull up at the last minute, skimming the waves while pursuers fell into the sea. More than once aerial acrobatics brought the stringbag home safely. Once, Flt. Lt. Charles Lamb, who later wrote the book To War in a String Bag, caused two pursuing Italian fighters to crash into one another when he turned sharply. On more than one occasion, a Swordfish skimmed the water with her wheels and still had power to lift off again.

The Swordfish had to rely on maneuverability because she had little in the way of effective armament. A .303 caliber (7.7mm) vintage World War I Vickers gun was mounted in front and fired through the propeller. A rear gunner could shoot an old fashioned Lewis gun, also of .303 caliber. One amused pilot called the guns, “One stage above the bow and arrow.”

At the beginning of the war, there were no radios aboard these planes, and communication with other planes or ships was accomplished with handheld lights using code. Internal communication among the plane’s aircrew was accomplished by a speaking tube, which proved amazingly effective.

Laying Mines and Sinking U-boats

The Swordfish began to earn her keep during the Sitzkrieg, or phony war, when neither Germany nor the Allies committed land forces to the fighting. The naval war, however, was in full swing. U-boats went to work on Allied commerce right away, and the few British aircraft carriers with stringbag squadrons aboard went out to hunt them down.

It was not a one-sided fight. When two torpedoes from a U-29 sank the aircraft carrier HMS Glorious, she went down with her entire complement of 24 Swordfish.

The Swordfish was also active in laying mines outside German ports. This was done at night when the slow speed of the lumbering planes did not endanger them. The biplane could hide in the dark with relative impunity. When attacking from altitude, the pilot could throttle back the engine and glide silently to his target.

When the phony war got hot, the Swordfish was in the thick of it. During the Second Battle of Narvik, the British bottled up seven German destroyers in a deep Norwegian fiord and determined to go in after them. The elderly battleship HMS Warspite led a flotilla of British destroyers into the narrow fiord. Stringbags catapulting off Warspite served as artillery spotters, locating and reporting the hiding places of the seven German destroyers. One of the biplanes shared in a kill by dropping a bomb on a German destroyer.

During that same battle a Swordfish spotted and sank the German submarine U-64. It was the first time an airplane had ever sunk a submarine. Later in the war, a Swordfish would be the first plane to sink a submarine at night. The Swordfish excelled at submarine warfare. For the duration of the war, squadrons of the mighty biplane flew off tiny escort carriers to keep watch over vulnerable Atlantic convoys. They also flew these missions for the Royal Canadian Navy. At the end of the war the Swordfish was still flying in convoy escort duty and had claimed 22.5 U-boat kills.

The war moved fast after the invasion of Norway. Soon the panzers were rolling through Holland and Belgium, trapping the British Expeditionary Force at Dunkirk. Though not designed for the purpose, the Swordfish dropped their bombs in the path of the onrushing Germans on the ground. During the evacuation, the busy biplanes kept watch on the sea lanes day and night to prevent German E-Boats from interfering with the desperate evacuation of British soldiers from the beaches at Dunkirk.

On Duty in the Mediterranean

The ungainly looking Swordfish was also making a name for itself in the Mediterranean, participating in the highly successful attack against the French fleet at Oran. Swordfish torpedoes sank the battleship Dunkerque and scored a bomb hit on the battleship Strasbourg.

In the wine-dark seas of the Eastern Mediterranean, 24 Swordfish flew from Egypt to Greece to support the Greeks against the Italians, and later the Germans. Flying at night from a secret base in Albania behind Italian lines, the Swordfish ranged the Adriatic in search of Italian shipping. The efforts of Swordfish pilots caused the enemy to temporarily abandon the port of Valona on the Albanian coast, creating havoc with supply hungry Italian troops in Greece.

The Swordfish and their pilots paid dearly for their success. Only three of the original 24 with their crews made it back to Egypt. In a tribute to their worth, a captured Swordfish pilot was traded in a prisoner exchange for an Italian general and two majors.

An Effective Weapon Against Enemy Shipping

Meanwhile, in Malta the Swordfish was used continuously as a night bomber. In the summer of 1941, the planes were fitted with radar for detecting surface vessels. Now able to “see” at night, the biplane pilots were highly effective at sinking Italian transport ships en route to North Africa. In the dark, even with an agonizingly slow airspeed, the torpedo plane was invisible.

During a seven-month period, the stringbags accounted for 50,000 tons of Axis shipping each month. The damage done to the Italian merchant marine convinced Rome to stop trying to supply Italian troops by sea. General Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps, German units sent to bolster the Italians in North Africa, also suffered supply shortages. By war’s end the Swordfish collectively accounted for a million tons of enemy shipping sunk.

The Attack on Taranto Naval Base

The most famous of the Swordfish’s exploits and the most important in military terms was the strike on the Italian naval base of Taranto on November 11, 1940. Located in the arch of the Italian boot, Taranto was the home of Italy’s powerful fleet. The harbor was well protected by barrage balloons and antiaircraft guns. The bulk of the Italian fleet lay there apparently safe at anchor. The British Admiralty envisioned a night raid on Taranto using carrier-based planes from HMS Illustrious. The Swordfish was the best and only aircraft for the job.

For this mission, the Swordfish’s third crewman, the rear gunner, was replaced by an extra fuel tank. The extra tank increased the range of the Swordfish from 200 to 900 miles, but it also increased the danger to the two crewmen. If the plane was hit by ground fire or attacked by fighters, the large tank of volatile aviation fuel was not shielded in any way other than the canvas that covered the fuselage.

Two waves of stringbags took off under a full moon. They flew at three different altitudes. The first three planes of the first wave of 12 aircraft carried flares to illuminate the harbor. They flew at 5,000 feet and drew defensive fire upward. A second group attacked from 1,600 feet, and, using dive bomber style tactics, accelerated their limited speed to 200 miles per hour in a power dive before leveling out at 90 feet to make their torpedo runs. The third group attacked at sea level, flying between the defensive balloons and their deadly cables. A second wave followed within the hour.

Two planes were lost during the raid, but significant damage was inflicted on the Italian fleet. When the smoke cleared at the port of Taranto, one battleship was sunk and two others severely damaged. A cruiser and a destroyer were also damaged, and an oil refinery was destroyed. The balance of power in the Mediterranean had shifted in favor of the Allies, helped tremendously in one night by 18 antiquated biplanes.

In Tokyo, the Japanese carefully studied the British plan of attack, which bolstered their belief that a successful surprise attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor was possible. Aerial warfare was changed forever.

The Swordfish also played a leading role in the Battle of Cape Matapan. The skillfully piloted biplanes damaged the Italian cruiser Pola and the battleship Vittorio Veneto.

An Easy Target During Daylight

The Swordfish racked up an impressive number of victories, but her weaknesses were also apparent. In February 1942, three German capital ships, the battlecruisers Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and the cruiser Prinz Eugen, were anchored at the French port of Brest. The big German ships were exposed to the threat of British air and sea power. The Germans determined to move them to the safety of ports on the Baltic Sea.

The three German ships got up steam on a dark night and headed through the English Channel at daybreak. The Channel Dash, as it was called, was supported by overwhelming German air cover for the few hours needed to make the run. No British warships were available to contest their passage.

The word went out for land-based Swordfish to stop the German flotilla. Six of the aging biplanes armed with torpedoes took off from airfields in southern England. All six were shot down before they could get within range. The Swordfish, nearly invulnerable at night, was an easy target when encumbered by a heavy torpedo in the harsh light of day.

The Swordfish was one of the few planes that was operational during the entire war. Unlike more sophisticated aircraft, the Swordfish was comparatively easy to assemble. Altogether, 2,396 of the biplanes were delivered. Later models featured a more powerful engine, an enclosed cockpit, and metal underwings with hard points for attaching rockets. The British attempted to replace the aging war bird with another Fairey model, the Barracuda, but the Swordfish outlived its successor.

By war’s end, Swordfish pilots could claim to have sunk over a million tons of enemy shipping. Twenty-three enemy warships were damaged or sunk. When England stood alone, the Swordfish proved to be a powerful weapon. The record of the antiquated stringbag compares favorably with any combat aircraft of World War II.

Glenn Barnett is a frequent contributor to WW II History. He lives in Los Angeles and is writing a book about the Roman invasions of Iraq.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments