By Eric Niderost

It was the custom for King Alfred of Wessex to celebrate the Twelve Days of Christmas at his royal palace at Dorchester, in the county of Dorset. Alfred’s great hall was the heart of the palace, a great timber structure that was the setting for the many feasts that marked the holiday.

During such a feast the king and his retainers would crowd into the hall, where trestle tables of food would await them. Women would start serving mead and ale and perhaps a little wine. The ealdormen (noblemen) and thegns (thanes, feudal lords) drank freely, the excess running down bearded faces, and as liquor loosened tongues the hall was filled with loud boasts and raucous laughter

The winter of ad 877-878 was probably a typical one. The English countryside was snowbound, cold, and forbidding, but inside the hall was cozy and welcoming, warmed by the bodies of the guests and the presence of a large hearth fire in the center. Dancing flames caressed the sides of a water-filled iron cauldron that was suspended from a roof beam, and as the water boiled the air was scented with the pungent odors of cooking meat.

Toasts were given, and no doubt many wished King Alfred “wes hael” (“good health” in Old English). Musicians plucked at harps, and at intervals boisterous thegns quieted enough to listen to ascope (storyteller) regale them with stories of mythic warriors and glorious deeds. But comforting legend was soon displaced by frightening reality. Alfred received word that a huge Danish army under the Viking leader Guthrum was sweeping into Wessex, apparently bent on conquest.

Danish Attack Catches Alfred Off Guard

This was quite literally sobering news; minds befuddled by drink must have quickly cleared. Viking raids were an old story, but this incursion was serious. For one thing, the Saxons had been caught completely off guard. Wessex did not have a standing army, only a levy called a fyrd that was summoned when needed. The fyrd was composed of thegns, members of a warrior class that owed allegiance to the king or one of his ealdormen. When a crisis passed, or a campaign ended, the thegns scattered to the four winds, going back home to run their own large or small estates.

Alfred was thus faced with a crisis of monumental proportions. The only forces that were readily available were his own personal bodyguard, the hearthweru (literally “hearth-guard”), but they numbered only around 300 men. The Vikings had a huge army of perhaps 5,000 battle-hardened, professional warriors. Guthrum made his move shortly after Twelfth Night, seizing the royal manor of Chippenham to use as a base of operations.

The central part of the kingdom, the area covered by the English counties of Wiltshire and Hampshire, now lay in the path of the invaders. Towns and villages were thoroughly looted, then put to the torch. Saxon peasants were cut down or trussed up to be sold as slaves. The Vikings were pagans, worshiping their own pantheon of Norse gods, which made them even more sinister in Saxon eyes. As “heathens” they looted churches and monasteries with equal gusto, slaughtering the monks, priests, or nuns who had the misfortune of falling into their hands.

Alfred Retreats to Somerset

Alfred was only 28 at the time, but he possessed a wisdom and experience beyond his years. His decision would not only affect Wessex, but would determine the entire course of English history. If he made the wrong choice, he might lose his throne and perhaps his life. Yet as Alfred sat in his Dorchester long hall, with a score of ealdormen and thegns looking to him for leadership, the situation seemed well nigh hopeless.

Word of Viking depredations spread like a verbal plague, infecting all with an unreasoning panic. Those who could, fled, and because Wessex hugged the southern coast of England many crossed the Channel into France. Others stayed and submitted to Viking rule. Alfred would not submit; surrender was not a viable alternative. He could flee to France, as some of his thegns and ealdormen had done, but to Alfred this was also out of the question.

He decided to retreat to Somerset, in what is now called the West Country. In the ninth century the area was a patchwork of tidal marshes and thick alder forests, ideal for concealment and defense. There were scattered villages, and some land was under cultivation, but these were islands of civilization tenaciously rising above a vast wilderness. Poor drainage conspired with spring tides and westerly gales to inundate whole sections of Somerset to a depth of five or six feet in places.

The king and a small retinue made their way to these Somerset marshes, eventually deciding to make Athelney their home base. Athelney was a small patch of about 30 acres that barely rose 40 feet above the surrounding marshes. Alfred sent his men to work felling timber, and soon a fort was constructed that would serve as the king’s home for the next few months.

There was no question that Alfred was in reduced circumstances, or that the situation was still bleak. The king was suffering a kind of internal exile, far from the power and prestige he had enjoyed on his royal estates or in his capital at Winchester. The timbered palace halls, full of the rich tapestries and books he loved, was now replaced by a rude fort in a swamp. The praises of retainers and the songs of minstrels were rudely replaced by the plaintive croaking of frogs.

Not only was Alfred’s kingdom reduced to a few scant acres, but his subjects now were just a small band of loyal retainers. There were a few thegns, for the most part members of his bodyguard; some court officials; and most likely a handful of servants. In a sense, Alfred became a kind of “Robin Hood” prototype, a charismatic fugitive who started to stage hit-and-run raids on a far more powerful enemy. Athelney became Alfred’s “Sherwood Forest,” but there the parallel ends. Alfred needed to be more than a guerrilla leader if he hoped to wrest his kingdom from the Vikings’ rapacious grasp.

Vikings: Pagans Who Relished War

Who were these Vikings who were poised on the brink of conquering all England?

“Viking” is a kind of generic term for warriors who hailed from Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. They burst upon an unsuspecting Europe like a plague of locusts, consuming everything in their path. They fanned out in all directions, seeking plunder, slaves, and glory. Historians still debate the underlying reasons for this sudden wanderlust, and theories run the gamut from the need for personal prestige to overpopulation. For the most part, Danish Vikings ravished Britain, while Norwegians ranged to such northern climes as Iceland and Greenland. Swedish Vikings, called “Rutosi” by the Finns, traveled to Russia, whose name is probably derived from that term.

The Vikings—the term probably comes from the old Norse term vik, or “creek”—were pagans who relished war. Their pirate raids were facilitated by their longships, some of the finest vessels ever created by the hand of man. The longship was superbly crafted, sleek and swift, and its shallow draught allowed it to cross oceans or navigate rivers with equal aplomb. Its square rig was such that it could tack against the wind—always useful for escaping an alien shore after a raid.

The average longship carried about 40 men, more if absolutely necessary. But recently archaeologists uncovered the remains of a longship near Roskilde, Denmark, that measured an amazing 118 feet from prow to stern. It its prime it must have carried a hundred men, and was propelled by about 40 rowers on each side. Not all Viking ships were this gigantic, but it underscores the sophistication of Norse naval engineering.

Early Raids Sent a Shockwave of Terror Through England

The first Viking raid on England occurred in the summer of 787 ad, when three Viking longships landed on a beach near Dorchester. A royal reeve (official) named Beaduherd rode out to investigate, thinking that these were foreign merchants out to sell their wares. But these visitors were out for plunder, not profit, and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle laconically notes that “he was killed on the spot and all those that were with him.” This was the beginning of a series of Viking incursions that were to last in one form or another until 1066.

Coastal monasteries were among the first to fall victim to Norse depredations. They were enormously rich, accessible, and virtually defenseless. In 793 the great monastery at Lindisfarne was sacked and burned, an act of vandalism that sent a shockwave of terror through England and western Europe. Lindisfarne was literally an outpost of civilization, a place where monks tried to keep the light of learning alive in a barbaric age. Today the illuminated Lindisfarne Gospels are considered one of the treasures of the Western world.

Years of burning, pillaging, and rapine alternated with years of relative peace. The English would patiently rebuild, rationalizing that these attacks were God’s punishment for their sins. During lulls between raids some dared hope their prayers had been answered, and that the “heathens” would no longer visit their shores. It was a hope shared by much of western Europe. “A furore normannorum libera nos, Domine,” they prayed, “From the fury of the Northmen deliver us, O Lord.”

The Vikings deserved much of this bad press, but modern historians try to present a more balanced picture. They point out that the Vikings were great craftsmen, shrewd merchants, and bold explorers. Nevertheless, they made a mistake in attacking monasteries, however ripe the pluckings. Monks were literate at a time when most could not read or write, and it was they who wrote the histories. The Vikings were skilled in arms, but the harried monks fought back by recording Norse misdeeds. In the context of centuries the monkish pen was mightier than the Viking sword.

There was also a certain irony in the Viking raids. The Anglo-Saxons had once been pagan invaders; now the tables were turned. Around 450 ad Germanic bands of Angles, Saxons, and Jutes poured into Britain, dispossessing the native Romano-Celtic population. Those that were not put to the sword were forced to flee into the mountain fastness of Wales or Scotland. By 700 the Anglo-Saxons had become Christian, and the island was divided into a number of small kingdoms. The former Roman province of Britannia was now Angle-land, or England.

Alfred’s Unlikely Rise to King

Around 850 the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms consisted of Northumbria, East Anglia, Mercia, and Wessex. Alfred was a member of the House of Cerdic, a dynasty that had ruled Wessex since its founding in the 6th century. When he was born in 849 his chances of ruling seemed remote. After all, he was the youngest of five sons born to King Ethelwolf.

There was something of a furor when Ethelwolf, then a widower, took a Frankish princess named Judith as his second wife. The fact that he was in his fifties and she was 13 scarcely fazed English contemporaries; they were more scandalized by the fact that she was enthroned as an equal, which was contrary to Saxon custom. Politics, not perversion, lay at the root of Ethelwolf’s nuptials. Judith was the daughter of Emperor Charles the Bold, and one could never have too many allies in a turbulent world.

Ethelwolf’s eldest surviving son Ethelbald usurped the throne in Ethelwolf’s absence, and for a time Wessex teetered on the brink of civil war. In a spirit of compromise the kingdom was divided between father and son, and bloodshed was avoided. Ethelwolf’s death two years later reunited Wessex under one head. But the kingdom was rocked by more scandal when Ethelbald, mesmerized by his stepmother’s beauty, married the 15-year-old widow.

When Ethelbald died prematurely in 860, he was succeeded by his young brother Ethelbert, who soon followed his sibling to the grave. In 865 Ethelred, the next brother, mounted the throne of his ancestors. In recognition of his importance, 16-year-old Alfred was appointed Secundarius, the king’s second in command.

In the space of a decade Alfred found himself catapulted from obscure aelening (prince) to a position a heartbeat away from the throne. Ethelred had sons, but they were mere boys. If something happened to Ethelred, chances were that the Witan, the king’s council, would choose Alfred as the next ruler.

There were sound reasons for considering Alfred as the next king. In the autumn of 865 the Danes returned, this time in force, with a large and rapacious host led by two brothers, Halfdan and Ivar the Boneless. Their father was Ragnar Lothbrok (Leather Breeches), a Viking chieftain infamous for sailing up the Seine and sacking Paris in 845. According to legend, Ivar had no bones in his skeleton, only cartilage or gristle. Although he had no backbone, he was anything but a coward.

The Danes landed in East Anglia, the smallest of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. They thoroughly cowed the East Anglians, who were more than happy to supply them with horses for their campaign. Northumbria was the initial target, a kingdom already weakened by internal dissension. The Viking Danes met and utterly defeated the Northumbrians at York.

The year 867 saw the Danes still entrenched in York. The countryside had been picked clean, plundered as far north as the river Tyne. Northumbria was a broken reed, pliant and submissive in the hands of its conquerors. Having created a desert and called it peace, the Vikings knew it was high time to move on to the rich, unsullied lands to the south. Mounting their stolen horses, the Viking host—called the “Great Army” by fearful Anglo-Saxon Chroniclers—began their migration in late 867.

Mercia, an Anglo-Saxon kingdom with strong ties to neighboring Wessex, was the Viking goal. Burhred, the Mercian king, had wed Ethelswith, Alfred’s sister. Burhred appealed to his brother-in law for help, and Ethelred responded with alacrity.

The Vikings had captured Nottingham, using the city as their base of operations. Safely ensconced behind the city’s stout walls, the Danes refused to come out and give battle. By the same token, the Anglo-Saxon army seems to have lacked the strength or the expertise to lay siege to Nottingham or breach its walls.

The Martyrdom of King Edmund

The campaign proved an embarrassing fiasco, and ended when the Vikings themselves voluntarily returned to York. They stayed in York about a year, then began a mass exodus to East Anglia in the fall of 869. It had been four years since the Vikings had landed in England, and East Anglia’s quick submission and ready cooperation had left them relatively unscathed. Now they were going to regret this one-sided pact they had made with the “devil.”

King Edmund of East Anglia was a man noted for his piety and goodness, but these sterling qualities left him ill equipped to deal with such a hard, merciless man as Ivar the Boneless. Ivar’s men fanned out into the countryside, burning, looting, and raping with impunity. As always, monasteries were singled out for special attention. Gold-encrusted altar pieces, reliquaries, and sacred vessels were carted off, and defenseless monks were cut down to lie in spreading pools of their own blood.

Ivar demanded that Edmund become his vassal, but the mere suggestion of such an arrangement filled the East Anglian king with loathing and horror. Legend insists that Edmund was captured by an advance party of Vikings while at his royal manor at Hoxne. Enraged at Edmund’s stubborn refusal to become his vassal, Ivar had the hapless monarch seized and bound to a tree.

Archers began to shoot arrows into the writhing body of the king, aiming the lethal shafts in such a way that they only wounded, not killed outright. This torture lasted for some time, until Edmund’s entire body resembled, it was said, “a hedgehog.” Punctured and bleeding from several dozen wounds, the king still lived. Tiring of the sport, the Vikings finally had his head cut off.

Since he had refused to accept a pagan lord and had died at the hands of heathens, Edmund was honored as a martyr to the faith. He soon became canonized and joined the Catholic communion of saints. The martyr-king was eventually laid to rest in a Suffolk town that took his name, Bury St. Edmunds.

The Saxons Band Together to Survive

But Saxon England needed a savior, not a saint—a warrior who could fight in this world, not offer prayers in the next. There were now only two independent Anglo-Saxon kingdoms left, Mercia and Wessex. The bonds between them were strengthened when Alfred married Ealhswith, a Mercian noblewoman who had blood ties to the Mercian royal house.

In December 870 the Danes were on the move again, traveling southwest into Wessex. No doubt Ethelred and the West Saxons had anticipated the attack, preparing themselves as best they could for the coming onslaught. The previous four or five years of intermittent fighting had transformed Alfred into a seasoned warrior, but this campaign would truly test his mettle. The Vikings poured into Wessex like a plague of avenging furies, seizing the Berkshire town of Reading as a base.

It was an old tactic, but nature itself came to the aid of the invaders. The Kennet and Thames Rivers formed a three-sided natural moat around the Danish encampment, and the raiders lost no time in throwing up an embankment on the fourth side. While some of the Vikings were busy digging into the Wessex earth, others formed foraging parties that ranged far into the countryside.

The Vikings grew careless as they scoured the countryside for provisions. One foraging party led by a jarl (chief) named Sidroc was surprised by Ethelwulf, Ealdorman of Berkshire, and a band of Saxon warriors. The Vikings were routed, and though the encounter was little more than a skirmish it put fresh heart into the Anglo-Saxons. But when Ethelred and Alfred tried to take the Viking earthworks at Reading they were repulsed with heavily casualties. Ealdorman Ethelwulf was numbered among the slain, causing recent elation to turn to gloom.

Luckily the Vikings chose to give battle, eschewing the safety of rivers and earthworks for the risks of combat. The first real battle of the campaign was fought at Ashdown (Ashdune), “Hill of the Ash,” somewhere on the northern slope of the Berkshire plain. Early medieval dates are sometimes hard to pin down, but the clash probably took place on January 8, 871. The Viking army was led by Halfdan and Bacsecg, two chieftains medieval Chroniclers call “kings,” and a host of lesser leaders called jarls.

The Armies Divide; Prepare for Battle

The Vikings, who had the advantage of high ground, deployed their men in two separate divisions. The two “kings” commanded one division, while the jarls led the other. On the surface there was little to outwardly distinguish the rival forces. Both preferred to fight on foot; to a Viking, a horse was merely convenient transportation to the battlefield. The basic tactical formation was the shield wall, the scildburh (literally “shield fort”). Each man’s shield was positioned in such a way as to overlap the shield of the man to his left.

Because the “pagans” had divided their army into two divisions, Ethelred felt he had no choice but to follow suit. The Anglo-Saxon army was likewise divided, Ethelred assigning Alfred to watch the jarl’s component while he opposed the Viking “kings.” Ninth-century battles were not set pieces, but they did contain certain time-honored rituals. To bolster fighting spirit and weaken enemy morale, rival armies indulged in battle cries, shouts, and insults. This “psychological warfare” was meant to goad an enemy into a rash and possibly premature attack.

The Saxons grimly waited for the signal to advance, bearded faces peering over their round shields. Iron helmets glinted in the early morning sun, its rays sparkling like diamonds over the smooth metal, and the Golden Dragon of Wessex standard flew above a prickly sea of spears. Saxons began to shout, hundreds of male voices joining in the battle cries. We don’t know what was shouted, but monkish Chroniclers of a later period recorded Ut Ut (Old English for “Out!, Out!”), Godemite (“God Almighty”) and Olicrosse (“Holy Cross!”). No doubt the monks omitted the bawdier utterances, preferring the sacred to the profane.

The battle cries and ritual taunts rose to a swelling crescendo, the voices amplified as they reverberated against the backs of shields. The Vikings probably replied with their own shouts and cries, but this verbal duel could not last forever. Each Saxon warrior had a thrusting spear and two or three javelins, the latter held with the shield hand. Viking javelins—light throwing spears—were launched at the Saxons, and the Saxons replied with their own missiles. The javelins were not aimed weapons, best for throwing at large, dense bodies of men. They had enough inertia to puncture shields with a dull thud, and here and there an anguished cry marked where a javelin hit living flesh.

Alfred Risks Usurpation to Attack

Alfred was eager to come to grips with the enemy, but needed Ethelred’s signal to advance. Where was his royal sibling? It turned out that Ethelred was in his tent, calmly hearing Mass. Alfred sent a messenger urging the king to make haste, but Ethelred would have none of it. Choosing piety over prudence, he declared he would not leave until divine services were ended.

This left Alfred with a terrible dilemma. The situation was deteriorating, and unless immediate action were taken the day could end in defeat. As Secundarius he took the initiative and ordered an advance. It could have been interpreted as an act of insubordination, a usurpation of the royal prerogative. But Alfred’s instincts were sound. The Saxon shield wall advanced up the rise, and as they clambered forward some men slipped as their feet failed to gain purchase on the smooth, chalky soil.

The two sides met near a stunted thorn tree that was rooted about halfway up the rise. When he heard the sounds of battle, Ethelred emerged from his tent and led his own division forward in support. The battle raged for hours, the thorn tree’s stationary silhouette rising above the carnage and marking its ebb and flow. Finally the Saxons gained the upper hand, and combat turned to slaughter. Surviving Vikings fled, leaving hundreds, possibly thousands, of dead and wounded on the field.

A Short-Lived Victory

It was a great Anglo-Saxon victory, and Alfred had every right to claim the lion’s share of the praise. But Ethelred and Alfred could not rest on their laurels. The Vikings were still not decisively defeated. The year 871 witnessed more battles, and unfortunately the Anglo-Saxon cause met disaster two months later at Meretun (probably Marten in Wiltshire). This time the tables were turned, and Ethelred and Alfred were defeated with heavy losses. Hard on the heels of this disaster came the news that a new Danish host, eager for plunder, had landed in England.

Calamity after calamity hit Wessex in mind-numbing succession, ending with the death of King Ethelred. He died suddenly a few weeks after Meretun; many historians hazard a guess that he died of wounds from that battle. The king left behind two young sons, but the times required an adult male on the throne. Alfred, the fifth and last son of King Ethelwolf, found himself proclaimed as ruler of the West Saxons.

There was more fighting after Alfred’s succession, but it was clear the Vikings had the upper hand. Alfred inherited a kingdom that was at the end of its tether; no less than nine major battles and numerous skirmishes had been fought in the span of a single year. The Anglo-Saxons were an agricultural society, and for all their warlike nature the thegns were not full-time professional soldiers. The fyrd was designed to deal with specific emergencies; when the crisis abated, the army disbanded.

Alfred Chooses to ‘Make Peace’

The thegns had to run their estates and supervise their ceorl peasants. Ceorls who were with the fyrd as laborers had to go back home to till the soil. By contrast, the Vikings were professional warriors who could stay in the field almost indefinitely. The king decided to contact the Danes and “make peace” with them. This was a euphemism for paying Danegeld (tribute), in essence bribe money to be left alone.

It must have been hard for Alfred to pay the Danegeld, but by accepting the inevitable the young king showed signs of true statesmanship. The ploy succeeded; the Vikings abandoned their camp at Reading and soon left Wessex altogether. Wessex preserved its independence and autonomy and was given five precious years to rebuild and recover.

Alfred could now turn his thoughts to other matters—though he probably kept a wary eye on events outside his kingdom. The king could read and write in Anglo-Saxon, the Old English that evolved into our modern tongue. The first line of the Lord’s Prayer, for example, “Our Father who is in heaven,” would be rendered “Ure Faeder, pu pe earl on heofonium.” Loving books, he eventually learned Latin and became a respected scholar.

But sooner or later, these peaceful pursuits had to give way to thoughts of war. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle took note of a disturbing new trend around the year 872: “Halfdan divided the Northumbrians’ lands, and from then on his men plowed and tilled them.” After a quarter-century of pillage and rapine these Vikings were settling down, starting to consider England home, not just a convenient place to plunder. The pirates were being transformed into plowmen, with a profound effect on English history.

The Fall of Mercia

While some Vikings were abandoning the sword for the plowshare, others still followed the old ways. A new generation of war leaders emerged, including the Danish chieftain Guthrum. The Vikings plundered the rich and fertile fields of Lincoln, then took up residence in Repton, the site where the kings of Mercia were buried.

Early in 874 the Vikings moved into the center of Mercia, and as events unfolded it was clear they were bent on permanent conquest, not temporary gain. King Burhred had no stomach for fighting, and when the Vikings approached, he fled and went into exile. Eventually he made it to Rome, a long and hazardous journey, and died there a few years later.

The fall of Mercia left Wessex as the only remaining independent Anglo-Saxon kingdom. Over the previous 20 years Northumbria, East Anglia, and now Mercia had been extinguished like so many guttering candles. Only Wessex kept the light of Anglo-Saxon England still brightly aglow.

In 875 Alfred was engaged in a sea battle off the coast of Wessex. An Anglo-Saxon named Ethelweard wrote later that “Alfred put to sea with his naval force, and the pagan [Viking] fleet met him, with seven tall ships; a battle ensues, and the Danes are put to flight, and one of their ships is captured by the king.”

These laconic comments mask a considerable achievement: The Vikings had been bested on their own natural element, the sea. But there was scant time to savor the victory, because Danes landed on the coast and seized Wareham. Wareham was protected by stout walls, and surrounded on three sides by water. Alfred raised the fyrd and managed to isolate the Danish contagion before it spread farther.

The Wareham Danes agreed to leave Wessex, sealing the pact with oaths sworn on gold amulets that had been sprinkled with blood and laid on an altar. It was said the Norse god Odin himself had made such an oath. They promptly broke their word and swiftly moved to Exeter, some 70 miles away. Alfred had his hands full, because he had to meet a great Danish fleet in Swanage Bay that was sailing to meet its duplicitous comrades at Exeter. Aided by a storm, Alfred scattered or sank this enemy fleet.

Perhaps unnerved by Alfred’s victory, the Exeter Danes made peace, and this time they meant it. They withdrew from Wessex in 877; when the year ended, a tired but triumphant Alfred could well believe he had seen the last of the Vikings for a long time to come. He was wrong, because Guthrum was preparing an invasion that would put the very survival of Wessex into question.

Patience Prevails at Athelney

As we have seen, Alfred and his court were taken aback by Guthrum’s sudden appearance in January 878. The king refused to surrender, nor would he flee to Europe like his fainthearted brother-in law King Burhred of Mercia. Instead, Alfred built a fort at Athelney, where he would await developments for a few months.

Why the delay? Alfred knew that the season for spring sowing—roughly from Candlemas (February 2) to Easter (April)—would soon be upon them. If he gathered the fyrd now, thegns and ceorls would have to abandon their homes and the planting cycle would be disrupted. Massive starvation and disease brought on by malnutrition might result. No, delay was the best course.

Many of the legends that embroider Alfred’s life center on this period. It is said that the king went into a Viking camp one day disguised as a minstrel. He was apparently a fair musician and had a good singing voice, because he got away with the impersonation. After gleaning some important information, the king slipped away, his enemies none the wiser. But the most famous legend concerns Alfred and the cakes, and there are several different versions of this tale.

It seems that Alfred stopped at a cowherd’s hut in the forest, where he was given temporary shelter. The cowherd’s wife set some cakes to cook near the fire, then went out for a while. The disguised king was deep in thought, and didn’t notice when the cakes began to burn. When the wife returned, she was horrified to see the scorched food, and gave the king a thorough scolding for being neglectful. Alfred felt many blows in battle, but nothing quite like the sharp edge of a woman’s tongue.

While Alfred lay low and made plans for the coming offensive, more disturbing news reached his ears. Vikings based in South Wales were the “wild card,” dangerous because they might take it into their heads to support Guthrum. Sure enough, a large Viking fleet of 23 ships under Ubbe Ragnarsson—reputed brother of Halfdan and Ivar the Boneless—landed in Devon. Luckily for the Saxon cause, a local Devon ealdorman named Odda decisively defeated this sea-borne threat.

Alfred and his men kept in touch with other Saxon groups, did reconnaissance, and probably did a little hit-and-run raiding too. But for the most part it was a waiting game, and seven weeks after Easter (about May 4) it was time to strike. Egbert’s Stone, a place about 25 miles east of Athelney, was selected as the location to marshal a resurrected Saxon fyrd. ealdormen and thegns were to assemble there and form an army. Generally, ceorls were not combatants, but it’s possible in the emergency that the better class of peasant ceorls also might have been added to “bulk up” the forces.

“His gefaegene waeron,” the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle writes of Alfred’s meeting with the men of Wiltshire, Somerset, and Hampshire—“They were glad to see him.” Well they might be, because the presence of a strong and charismatic leader gave them unity and purpose. At this time Guthrum and his Viking host were based in Chippenham, some 15 miles from Edington, the future battle site.

The Turning Point: The Battle of Edington

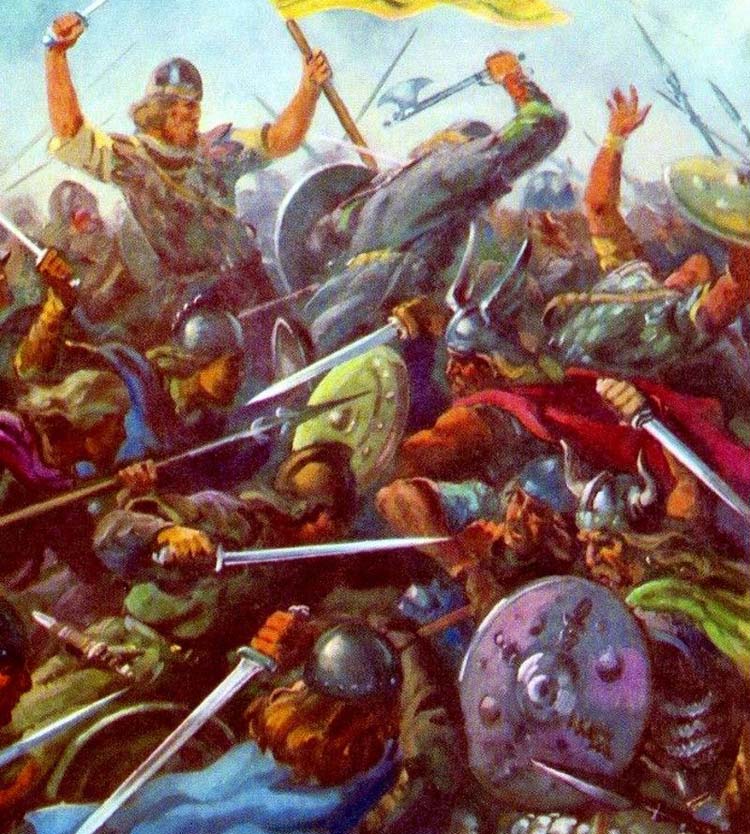

Edington is one of the decisive battles of English history, yet we know maddenly few details. Alfred’s biographer Asser tells us that Alfred and his men “closed ranks, shield locked with shield, and fought fiercely against the heathen host in long and stubborn stand.”

We can fill in the blanks by conjecture and some “educated guesswork.” There was probably a shield wall, as at Ashdown. When two rival shield walls came together in close combat the effect must have been horrific. Only richer thegns or high ealdormen had anything resembling armor, usually some kind of mail shirt. Most Anglo-Saxon men would be wearing their everyday woolen tunics that reached the knee and were belted at the waist.

The basic weapon for Saxons was the spear, and for Vikings the sword or axe. After javelins had been thrown, a thrusting spear was used for close combat. As the warriors neared each other, spears would probe for exposed flesh or unguarded postures. Spears gouged deep wounds into throats, spraying the ground with bright arterial blood; or probed for eyes, the weakest and most vulnerable part of the skull. Swords and axes bit deep into shoulders or hacked off arms with a single stroke.

The ground must have looked like a slaughterhouse, filled with broken weapons, dismembered corpses, pools of gore. Swords and axes rose and fell, until the once-bright blades were coated in blood. Even shields could be used as weapons; the metal boss in the center of a shield could inflict a powerful blow in a melee. Medieval combat was not for the faint-hearted.

Finally the Saxons gained the upper hand and the Vikings retreated. Thousands of Danes were cut down as they fled until the rout was complete. To the victor go the spoils, and in the aftermath of battle ceorls roamed the field stripping Viking corpses of valuables. If a Viking was only wounded and still alive, a ceorl’s scramaseaxe (long knife) could make short work of the victim by cutting his throat.

Alfred Finally Secures Wessex

The Viking survivors managed to reach Chippenham, followed by Alfred in close pursuit. The Anglo-Saxons blockaded Chippenham, compelling the starving Danes to surrender. Guthrum, who had survived the debacle at Edington, was one of those who capitulated.

The Vikings promised to leave Wessex, and to seal the pact Guthrum agreed to be baptized and become a Christian. The Vikings’ past record must have given Alfred pause, but this time Guthrum proved true to his word. The Viking chief and 30 of his men were baptized at Weedmore. Guthrum’s baptismal name was Athelstan, which means “royal stone.” In an ironic twist, Alfred stood as Guthrum’s godfather.

The Danish threat remained for decades, but never again in Alfred’s reign would Wessex be so close to extinction as it was during the years 871 to 878. Wessex actually expanded, and in 886 a partition treaty divided England between Wessex and the Danish Vikings. Northern and eastern England came under the sway of the Vikings, and was called the Danelaw—that is, under the rule of Danish law and custom. Wessex took the rest, including West Mercia and Kent.

Warrior, statesman, lawgiver, scholar in a barbarous age—Alfred of Wessex was a man of many parts. History knows him as “Alfred the Great,” the only English king to be honored with such an epithet.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments