By John F. Murphy, Jr.

On the morning of July 8, 1758, the largest field army yet gathered by the British Empire in North America stood a mile from a French stone fort in the forests of what was then the colony of New York. The name of this place was Ticonderoga and the fort was Fort Carillon. A major battle would not be long in coming.

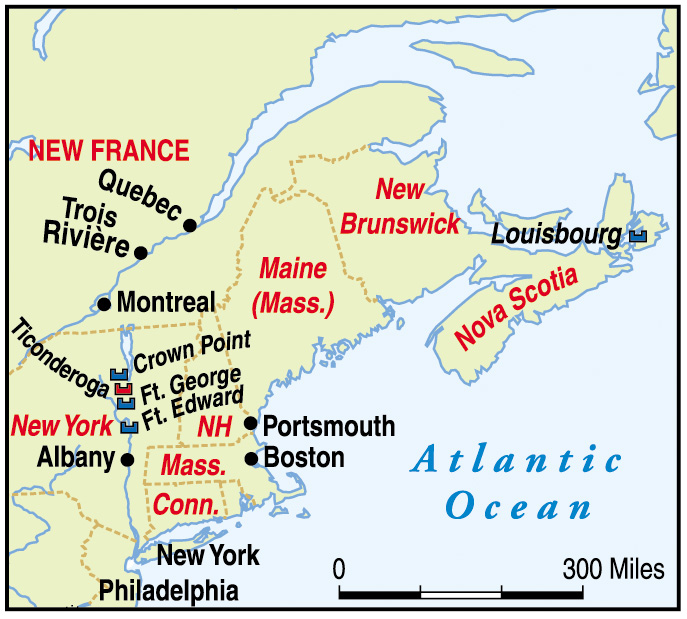

The scene had been set in the campaign plans for 1758 by “The Great Commoner,” British Prime Minister William Pitt The Elder, and the British Army’s Commander-in-Chief, Lord John Ligonier, who 13 years earlier had fought the French at Fontenoy in May 1745. Frustrated that the year 1757 had gone so terribly against the “forces of the Crown,” Pitt decided on a three-pronged attack that would forever break the French hold on North America. The northern strike would be led by General Jeffery Amherst against the Fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, guardian of the St. Lawrence River, which flowed through New France to the main cities of Quebec and Montreal. The western attack would be led by General John Forbes against Fort Duquesne at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers, the scene of General Edward Braddock’s defeat in 1755. The middle thrust would be commanded by General James Abercromby against France’s Fort Carillon—known to the Indians as Ticonderoga—which controlled the vital Lake Champlain/Lake George/Hudson River waterway stretching from New York City to Montreal.

‘Nabbycromby’ Put in Charge

Political influence conspired to put Abercromby at the head of a force of some 15,000 British and American colonial troops for this expedition. In fact, Pitt hoped that Lord George Howe, the older brother of William Howe, who was at that time the lieutenant colonel of the 55th Regiment, would take over operational command of the troops when the battle commenced. The British and colonial Americans treated Abercromby with disgust, knowing him for the tactical nullity that he was. As Francis Parkman wrote in Montcalm and Wolfe, the Americans called him “Nabbycromby” behind his back. Lord George Howe, on the other hand, was the soldier’s hero, beloved by British and Americans alike. James Wolfe, who in 1758 was serving under Amherst at Louisbourg, wrote to his father that Howe was “the noblest Englishman who has appeared in my time, and the best soldier in the English Army.” Wolfe, on the other hand, had dismissed Abercromby as being “infirm in body and mind.”

Abercromby’s army began to assemble at the southern end of Lake George during June. American colonial troops rallied from New England, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Connecticut. The New England colonies contributed mightily to the war effort in both money and men; New Hampshire sent one out of every three able-bodied Colonial fighters against the French. New Jersey made perhaps the most unique contribution of the American provinces: the Jersey Blues. Raised in 1755, the regiment was commanded in 1758 by Colonel John Johnson, and numbered approximately 1,000 men. Like the Virginia regiments, in which George Washington served this year as commander with Forbes against Fort Duquesne, the Jersey Blues could be considered among the most professional “regular” troops at the disposal of the colonial governors.

The British troops represented an amalgam of the most modern in British tactical thought and some of the most venerable regiments to carry the Union Jack above their battalions. These included the 1st Regiment (the Royal Regiment, later the Royal Scots), the 17th Regiment, the 27th Regiment (Inniskilling), the 42nd Regiment (the Black Watch), the 44th and 46th Regiments, the 55th Regiment, the 60th Regiment (the Royal Americans), the 80th Regiment, and the Royal Artillery. The Black Watch traced its origins to the independent Highland companies formed in 1725 to guard against Jacobite sympathies in the recalcitrant north of Scotland. The 60th Royal Americans and the 80th Regiment represented the latest in British tactical ingenuity. Unencumbered by the infantryman’s 60- to 80-pound burden, they were trained to fight as “light infantry” to counter the edge in forest warfare enjoyed by the French and their Indian allies.

British Begin Their Advance

After a month of boredom and inactivity, Abercromby finally gave the order for the troops to embark on the evening of July 4, 1758. After a night spent loading the boats, canoes, and bateaux (special heavy duty barges), the army began its voyage north on the lake to its meeting with Major General Louis-Joseph, the Marquis de Montcalm, the ranking French officer in North America.

Leading the way up the placid lake came Robert Rogers and his Rangers and Brig. Gen. Thomas Gage with his 80th Regiment of light infantry. Behind them, in three columns, came the remainder of the army and artillery on heavy flatboats. In the center column, the regulars were led by Lt. Col. George Howe with his 55th Regiment, while the American troops flanked the British on the right and left. The army was so vast, the Boston News Letter reported, that it virtually covered the entire surface of Lake George.

From the beginning, misfortune plagued the enterprise. By 5 pm, the armada had only covered 25 miles to Sabbath Day Point, where the boats pulled into shore to wait for baggage and artillery. To make matters worse, Abercromby gave orders to resume the advance at 11 pm, taking the terrible risk that the French and their Indian partisans might dash on them in the dark. Fortunately for the British, such a maneuver had not occurred to Montcalm. Instead, his rangers, under Captains Langy and Trepezec, only observed the oncoming enemy.

Around dawn on July 6, the army reached the Second Narrows, where Lake George approaches Lake Champlain. By noon, the entire force landed at a spot near Burnt Camp where Montcalm had set off to destroy Fort William Henry the summer before. A forward movement began with Major Rogers, Lt. Col. John Bradstreet, and Lord George Howe. (Rogers, a New Hampshire farmer, had raised his Ranger force at British request in 1756.) Before long, the head of the column was caught up in a thick wood. Parkman graphically described the plight of Abercromby’s men: “The guides [Rogers’ group] became bewildered in the maze of trunks and boughs; the marching columns were confused, and fell in one upon the other. They were in the strange situation of an army lost in the woods.”

A Stunning Loss

At the same time, the French rangers under Langy and Trepezec found themselves cut off from Fort Carillon. Numbering at most 350 men, they were slowly being surrounded by the British troops. The two French captains decided to try to work back to Carillon by following a serpentine route through the wilderness. Interestingly, the paths of both forces converged at Trout Brook. Lord Howe and Major Israel Putnam, serving under Rogers, were pushing ahead with a party of some 200 Rangers at the front of the leading British column. However, Rogers, with the bulk of the Rangers and the Connecticut regiments of Colonels Hineas Fitch and Elezaer Lyman, had become separated from Howe and Putnam.

Suddenly, the French challenge “Qui vive?” (“Who goes there?”), rang out from among the trees to the front. Supposedly, Putnam gave the response “Français,” but it was not believed. The French opened fire. Then the inconceivable happened. Lord George Howe fell to the ground mortally wounded, a French musket ball lodged in his chest. When the firing broke out, Rogers with the two colonial regiments turned around and caught Langy and Trepezec between the two British forces. Furious at the loss of Howe, the Rangers and colonials fought savagely. Some 50 of the French escaped, but Parkman records that “a hundred and forty-eight were captured, and the rest were killed or drowned trying to cross the rapids.”

Among the French killed was Captain Trepezec, but this was small consolation for the loss of Lord Howe. Rogers would write, “The fall of this noble and brave officer seemed to produce an almost general langour and consternation through the whole army.” On the French side, Colonel Louis Antoine de Bougainville, who had arrived in New France with Montcalm in 1756, wrote in his journal that Howe had “in the greatest degree those two qualities of heroes, activity and audacity…. Most glorious for him is the regret of his companions and the esteem of the French.”

The effect on the army, bereft now of its heart, was devastating. Major Thomas Mante later wrote, “From the unhappy moment the General was deprived of [Howe’s] advice, neither order nor discipline was observed, and a strange kind of infatuation usurped the place of resolution.” Immediately, Abercromby halted the advance and ordered the men to spend the entire night “under arms,” compounding their exhaustion. The next day, July 7, he ordered them to return to the landing spot near Burnt Camp, aggravating the loss of a favored officer with a disheartening retreat. Then, at noon, he reversed himself again, ordering Bradstreet to take a forward party of regulars and colonials to occupy the strategic falls of Lake George. Montcalm had given up the falls the night before, believing he could be overcome if the British took up position on neighboring high ground. By the late afternoon of July 7, the rest of the British forces had occupied the area of the falls. For a second time, Abercromby left his artillery behind.

The French Line at the Heights of Carillon

Fort Carillon had been built according to plans laid down by Sebastien Le Prestre, the Marquis de Vauban, during the reign of Louis XIV. It had been built by the engineer Michel de Lotbiniere; with construction beginning in October 1755. Montcalm, however, had decided not to await Abercromby—either behind the stone ramparts of Carillon, which stands on a thumb of land between Lake Champlain and Lake George, or back at the falls. Instead, Montcalm decided to make his stand on a ridge, in some accounts called the Heights of Carillon, about a half-mile outside the fort. According to Bougainville, Montcalm had designated the spot as a possible battle site when he reconnoitered the area on July 1 with his engineer officers, Nicholas Sarrebource de Pontleroy and Jean Nicholas Desandrouin. The next day, July 2, Montcalm gave the order to commence building blocking defenses, with the labor begun by the men of the Berry Regiment. Howe’s death gave Montcalm the opportunity to complete the job. As the work was undertaken, Montcalm had already thrown out a screen from the light infantry companies of the regiments, along with the usual rangers, to cover a wide zone around the fort to avoid the chance of being taken by surprise.

The troops assembled under the Lilies of France, which represented the French infantry of the Old Royal Regime. The regiments working on the defenses were the Royal Roussillon, Berry, Guyenne, Bearn, Languedoc, the Royal La Marine (actually raised from the Independent Companies of Marines in Canada, the Troupe de La Marine), and La Sarre. The Royal La Marine—dating back to Cardinal Richelieu and King Louis XIII in 1622—was the senior unit at the fort. When Bougainville saw the Royal Roussillon and La Sarre regiments marching into the seaport of Brest to board their transports, he had marveled, “What a nation is ours! Happy he who commands it, and commands it worthily.”

Since their arrival, many of the battalions of these regiments had endured nearly three years of almost continual war. Many of the soldiers now standing there were drafts from the Canadian militia. While the Royal Roussillon and La Sarre had arrived with Montcalm, and La Marine was a Canadian unit, most of the other French battalions had arrived with Baron Ludwig von Dieskau in May 1755. The Languedoc and La Reine Regiments had fought under Dieskau at the French defeat in the Battle of Lake George during September 1755. Montcalm had been sent out to replace Dieskau, who had been captured by the British commander, Sir William Johnson, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs.

Philippe de Riguad, Marquis de Vaudreuil, the governor of New France, recorded that the entire force numbered 4,760 men, including laborers drawn from the population of the colony, while Bougainville noted that Montcalm had some 3,526 men. Along the defensive line they were building, regimental flags proudly marked where the troops would stand. When the trees were felled, they were carried back to the line that had been traced by the engineer officers. The soldiers built a log wall which Abercromby would remember all too well in a July 12 letter as being “at least eight feet high.” The wall was made in a zig-zag manner so that every foot of it could be covered by murderous enfilading fire. Notches were left in the growing log breastwork as loopholes for musket fire. At some places, the top of the wall was layered over with sandbags to provide a higher level for shooting. Parkman believed that, owing to the height of the defenses, a banquette, or firing platform, must have been constructed behind it. A Swiss officer in the ranks of the Royal Americans recalled a total of three rows of loopholes in some places of the “French Lines,” as history has remembered Montcalm’s defense works.

The log barrier covered the entire width of the Heights of Carillon, with the rocky slopes on either side making flanking maneuvers almost impossible. Out to the edge of the clearing, the tall trees had been left pointing toward the direction of the attack, to break up any British formations when they advanced. Between the lines and the felled trees was the most wicked part of all. The engineers had directed the men to bring heavy branches up to the front of the French Lines and sharpen them, with the pointed branches thrust into the faces of the oncoming British and colonials. Hidden by the foliage, this barricade of sharpened branches, called an abatis, would be the last thing many of the attackers would ever see. By the night of July 7, the massive work was finished. A poignant observation concerning the French defenses was made by British Captain Eyre: “… unhappy for us, we presently found it a most formidable entrenchment and not to be forced by the method we were upon.”

Abercromby’s Missteps

That same evening, Abercromby made plans again for attacking Montcalm the next day, the morning of July 8. Yet his delay following the death of Lord Howe had not only enabled Montcalm to build his breastworks, but had also given General François Gaston de Levis time to hurry to his commander’s aid with 400 additional French regulars. Abercromby believed that Montcalm was to receive thousands of reinforcements at any moment, and the appearance of Levis in the night must have confirmed his fears. Had Rogers’ Rangers performed adequate scouting, Abercromby would have known that the nearest French post, Fort St. Frederic to the north at Crown Point, had few enough troops for its own garrison. Although some 250 were hurried forward to reinforce Montcalm during the fight, Abercromby’s conclusions about reinforcements were still exaggerated. The two forces had drawn so close that the British, as Bougainville wrote, were “not a cannon shot from our abatis.” All day on July 7, in fact, a brisk fire had been maintained by light troops on both sides. Abercromby himself had moved up to take position near a sawmill at the Falls of Lake George.

Although a fearsome challenge, the French Lines could soon have been smashed to kindling by the guns of the Royal Artillery. Most campaigns saw the British in North America using no more than 12- or 24-pounder cannon (derived from the weight of the shot), due to the forested terrain through which the gunners would have to haul them. Nevertheless, such cannon shot would have blown Montcalm’s strongpoint apart. Each cannon ball hitting the wooden wall would have sent hundreds of sharp wooden splinters among the French soldiers, killing and maiming with terrible wounds. Moreover, the wood of the French defenses had become tinder dry in the July heat, causing heroic French soldiers to dash forward, braving English fire, to put out small blazes before they could spread and engulf the entire position. Further, every British “train of artillery” would most likely have had with it portable furnaces that could heat round shot until it was incandescent, turning it into the “hot shot” used to set fire to enemy ships in naval battles. These projectiles could have set the abatis ablaze. Had the British artillery then opened fire with deadly grapeshot, any Frenchmen who tried to extinguish the fires would have been cut down.

On the morning of July 8, Abercromby gave the order for his light troops, Rogers’ Rangers, Colonel Gage’s light infantrymen, and Bradstreet’s special boatmen unit to push forward to make first contact with the French. The battle was opened by Lieutenant James Clark of Captain John Stark’s Ranger company at about 7 am. Surprised by an ambush of French light troops, Clark and his men held their ground. Then, according to John D. Lock in his To Fight with Intrepidity, “Rogers deployed his corps on line and advanced. Acting as skirmishers, the Rangers advanced in the center, Gage’s light infantry on the right flank and Bradstreet’s Bateauxmen to the left.” At 10 am, Rogers received the order to drive back the French to make room for the general advance. The aimed musketry of the light troops—as opposed to the volley fire of the regulars—had a telling effect on the French to their front, and forced them to retreat.

Meanwhile, across the LaChute river running from Lake George past the fort to Lake Champlain, William Johnson had arrived atop Rattlesnake Mountain, later Mount Defiance, with some 450 Choctaw, Delaware, and Iroquois Indians. Properly deployed, this force could have provided a harassing diversion at the time of the main British attack. Instead, the tribesmen refused to take an active part in the affair, preferring to watch the British and French kill each other. Their contribution would be to fire off a few shots at the French at the limit of their range. Bougainville even wrote contemptuously, “We amused ourselves by not replying.” Perhaps one Frenchman was wounded by Johnson’s desultory musketry.

It was also about this time that Abercromby demonstrated his only tactical initiative of the day. He sent a force in 20 bateaux under British engineer Lieutenant Matthew Clerk to try an outflanking maneuver by way of the river from Lake George. Some of the boats in the front of the column had cannon mounted in them as well. The Canadian Volunteers of Captain Villiers, supported by militia and grenadiers from the Royal Roussillon under the Sieur de Poulhariez, opened up a hot fire on the boats. More importantly, the flotilla came under the guns of the fort. These were crewed by members of the (French) Royal Artillery—most likely the canoniers-bombardiers from New France—and soldiers from two battalions of the Berry Regiment. The 10 cannon in the South Battery of the fort, almost directly above the amphibious force, opened fire, the discharge of the guns echoing off Rattlesnake Mountain. Two of the lead vessels sank, and the rest turned around. Clerk was killed.

Abercromby’s tactical sense may have been undervalued all these years. Although no written orders regarding this part of the battle appear to have survived, it could be that the flanking movement of the boats on the river may have been timed to coincide with Johnson’s deployment of his warriors on Rattlesnake Mountain. Had Johnson been able to get the Indians down to the bank of the river, the fire of their musketry could have had a devastating effect on the French position, a similar tactic to that which had such a withering impact in his combat with Dieskau’s army in 1755. The Indian musketry could have enfiladed the French Lines and also possibly have forced the gunners within Carillon to take shelter behind its stone ramparts. With such a threat on his left flank, Montcalm would have had to commit his grenadier reserve there, thus relieving pressure on the main British attack. Moreover, if the British cannon on the bateaux could have been brought ashore, they would have raked the entire French defenses with solid shot and grape. Thus, the unwillingness of the warriors, who Johnson could influence but never command, might have cost Abercromby the battle.

The Doomed Advance

At 12:30 pm on July 8, Abercromby gave the order for the advance—without artillery support. The first line was formed by the New York and Massachusetts colonial regiments. The British regulars followed, with the left of their line under Lt. Col. William Haviland of the 27th Regiment and Lt. Col. John Donaldson of the 55th commanding the center. The right of the line was commanded by Lt. Col. Francis Grant of the Black Watch. The British grenadiers converged into a single unit under Lt. Col. Frederick Haldimand of the Royal Americans. The Connecticut and New Jersey troops formed the third line of attack.

While the pipes of the Black Watch could be heard skirling ahead (no drums had yet been added to the kilted regiments) and the first miter caps of the grenadiers appeared, the French awaited them in position. To the left were the La Sarre and Languedoc Regiments, and the regimental light companies that had arrived under cover of darkness with Levis the night before. The Royal Roussillon and Berry battalions, along with the rest of the light companies, formed the center under the eyes of Montcalm. The right of the line—the place of honor—was manned by the soldiers of the Bearn, Guyenne, La Reine, and La Marine Regiments. Canadian militia and Indians hovered along both flanks to cover the broken ground. Levis was in command of the right wing and the Chevalier de Bourlamaque, who had been at Carillon since May, led the left. With Montcalm was a reserve of light infantry and the regiments’ grenadiers to use if a British broke through the main line.

With the British marching into the killing ground of the felled trees, the rapping of the French drums called out their grenadiers, light companies, and the Canadian Volunteers, who fired a long-range volley at the oncoming enemy. They then retired behind the French Lines. Three lines deep, with the regulars in the middle and the colonials on the flanks, Abercromby sent in his first assault. The infantry delivered their attacks uncoordinated, giving the French defenders opportunity to maul each advance in turn. De Lancey’s New Yorkers on the British left made first contact. The right advanced before the troops of the center, and individual regiments moved forward when ready. Early or tardy, each regiment came to grief in the abatis. John Bremner wrote in his diary that “the ground was clogged up … with logs and trees intermixed with brush which greatly interrupted the speedy and regular march of our troops; and as they marched three deep they had enough to do to fill up the vacant places made up [from the] dead and wounded which fell.” The right side troops tried an outflanking movement, but they were stopped by determined fire from the muskets of La Sarre. Only the light company troops and the Rangers, concealed behind trees, made, as Bourlamaque remembered, “a most murderous fire on us.” For nearly an hour, the slaughter continued before the ravaged battalions retreated.

Commanders begged Abercromby to send for the artillery to smash up the French Lines, but he refused. Any attempt at a turning movement had died with the two boats, and the general had nothing to offer his beleaguered men but the same orders he had given their colonels that morning: “March up briskly, rush upon the enemy’s fire, and not to give theirs, until they were within the enemy’s breastworks.”

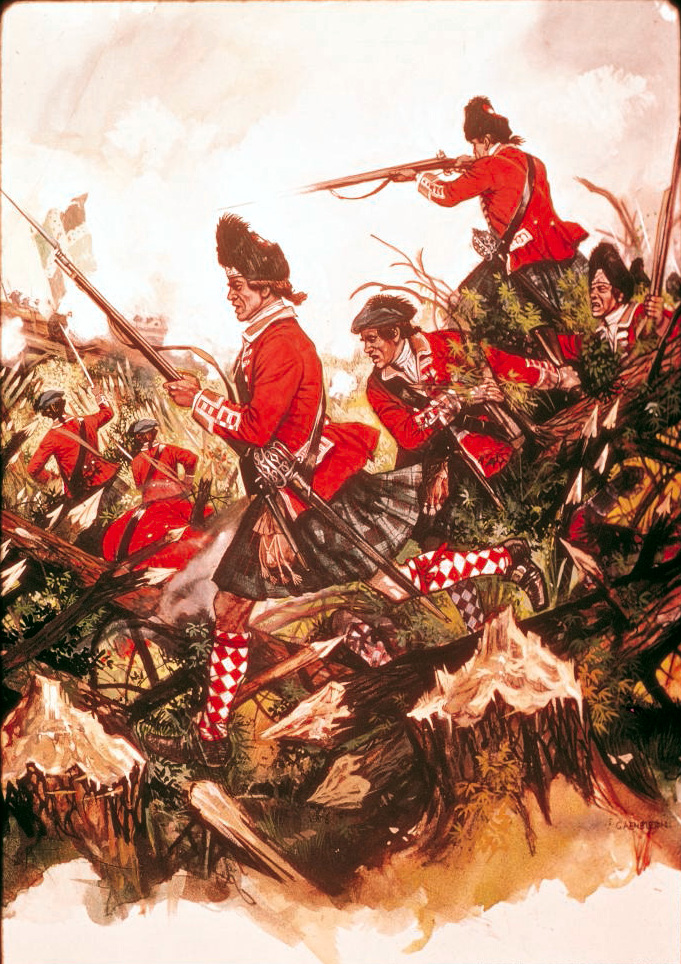

The Valiant Black Watch

At about 5 pm, the moment of truth came. After almost incessant fighting all day, a British column, with the Black Watch spearheading, made a furious attempt to breach the French Lines. Heading for the Guyenne and Bearn Regiments, the Highlanders used their heavy broadswords to chop through the abatis. In spite of fearsome casualties, the kilted warriors roared the clan war cries and pressed onward. Montcalm headed for the danger spot with his reserves, and Levis took men from the right to buttress the two regiments. During the fierce approach, Duncan Campbell, Laird of Inverawe, fell amid his countrymen. Legend has it that, long before, he had dreamed of his death at a place called Ticonderoga, a word he did not then understand. A French musket ball shattered an arm and he died nine days later. He was buried at Fort Edward, south of Lake George.

Although deprived of their major, the Black Watch fought on. A Canadian militiaman who faced them a year later at the decisive battle for Quebec in September 1759 described the “Forty-Twa” coming at him with “streaming plaids, bonnets, and large swords—so many infuriated demons!” Lieutenant William Grant of the Black Watch saw Captain John Campbell and some other soldiers climb over the French wall and down the other side, where they slashed around them with their claymores until killed by French bayonets. Frustrated there, the Highlanders, according to Bougainville, shifted to their left to try to get through the Royal Roussillon near the center.

Finally, at 7 pm, the Black Watch broke off their savage attempt, but only because they were begged to do so by their own officers. As Bernard Fergusson, a former lieutenant-colonel in the regiment, wrote, “More than half the men of the Regiment and two-thirds of the officers had been killed or wounded.” A regimental officer who survived that terrible charge would remember, “Their ardour was such that it was difficult to bring them off. When shall we have so fine a regiment again?”

The failure of the attack of the Black Watch brought an end to the horrible fighting. With Rogers’ Rangers covering them, the battered troops retreated. Montcalm, however, was in no way able to pursue. Bourlamaque had been seriously wounded (but would survive), while Bougainville received a slight wound to the head. Levis finished the day with two British musket balls through his hat. All of the regular French battalions had captains and lieutenants killed. Bougainville recorded 42 officers and nearly 400 men killed or wounded. That night, as immortalized in the painting by Henry Ogden in the Fort Ticonderoga Museum, Montcalm walked among his troops to receive their accolades.

Yet, the French could not rest. Montcalm and his officers thought Abercromby would return to the attack in the morning—this time with his artillery. The entire night was spent strengthening the French Lines against a renewed attack—which it was unlikely the French could withstand.

Abercromby Loses His Nerve

On the morning of July 9, the company of Canadian Volunteers cautiously advanced on a scouting mission. They found no one. The Volunteers then probed as far as the Falls of Lake George, but no British or colonials were to be seen. Montcalm and the French could hardly believe it. The next morning, Levis took all eight French grenadier companies to confirm what the Canadians had reported. Bougainville recorded that all they was found was “wounded, provisions, abandoned equipment, shoes left in miry places, remains of barges and burned pontoons.”

Bougainville suspected the British had retired with heavy losses. In fact, compared to the number involved, their losses were slight. Edward P. Hamilton, the former Curator of the Ticonderoga Museum, estimated British casualties at some 1,610 killed, wounded, and missing.

The incredible had happened. Following the defeat of the Black Watch on July 8, Abercromby had simply lost his nerve. To the great consternation of the troops, who wanted to return to the assault the next day, “Nabbycromby” had ordered a hasty withdrawal to the far end of Lake George. Nothing had been gained.

Marking his amazing triumph, Montcalm raised a tall cross on the battlefield, a replica of which still stands on the grounds of the restored fort. The cross bears a statement Montcalm himself wrote (here translated from the French):

“Soldier and chief and rampart’s strength are naught;

Behold the conquering Cross! T’is God the triumph wrought!”

If indeed God was on the side of the French that hot, humid July day, He was helped by a general who could not imagine defeat in the face of high odds, and who inspired his men to believe the same.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments