By Eric Niderost

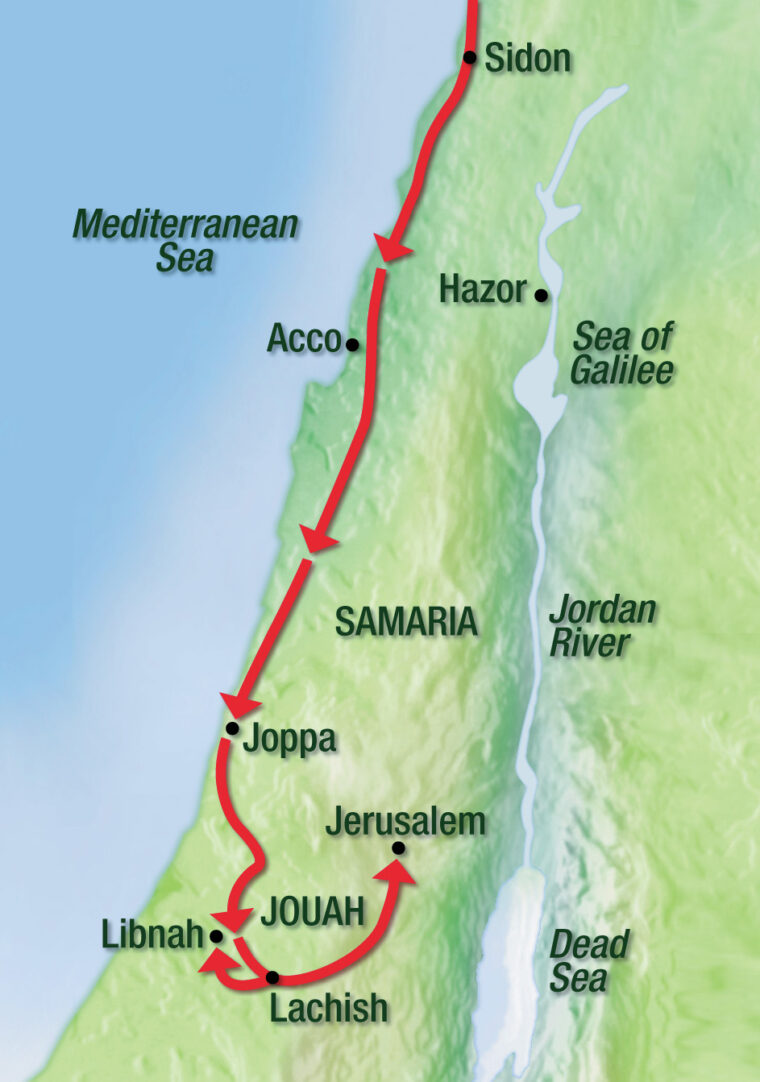

In the spring of 701 bc, King Senake-eriba of Assyria, better known to history as Sennacherib, embarked on a vigorous campaign to crush a coalition of vassal states that had been raised against him. Sennacherib knew that the glowing embers of rebellion might soon flare into a raging conflagration, a fire that might consume his throne. The Assyrians maintained order by making an example of those who dared to throw off their yoke, and this campaign would be no exception. The flames of rebellion would be extinguished by the flow of blood.

Heavily Fortified City Presents Steep Challenge To Assyrians

Just now the Assyrian army was besieging Lachish, a fortress town in the kingdom of Judah about 30 miles southwest of Jerusalem. King Hezekiah of Judah had been one of the ringleaders of the insurrection, proclaiming his defiance by withholding tribute to Sennacherib. The foolish Hebrew monarch had sown the wind; he would now reap the whirlwind.

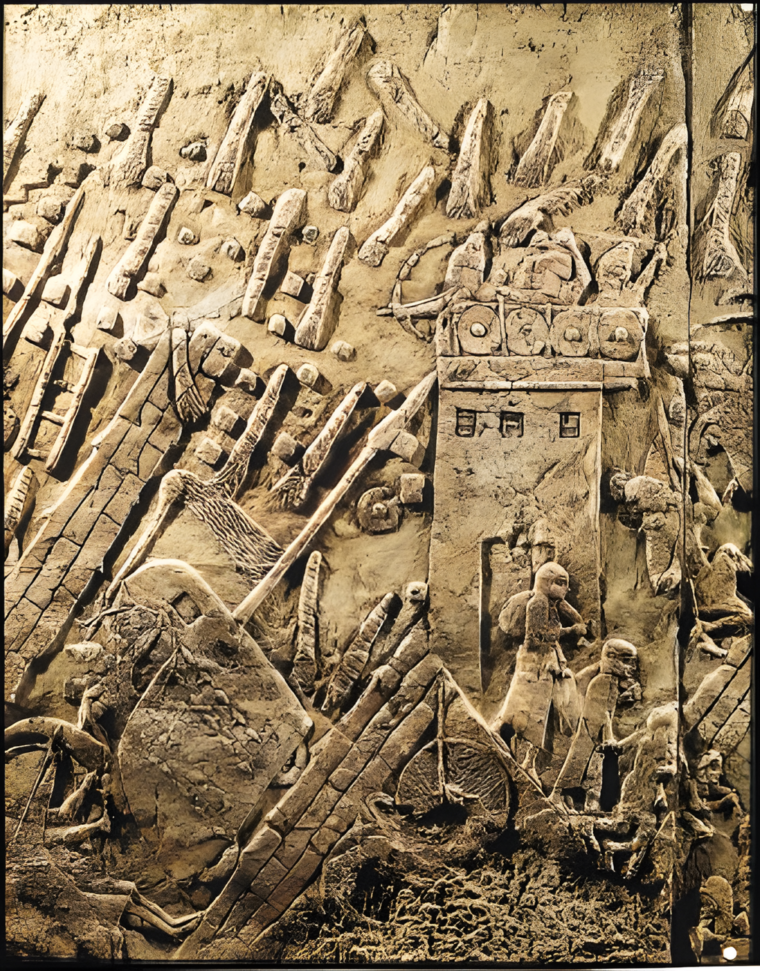

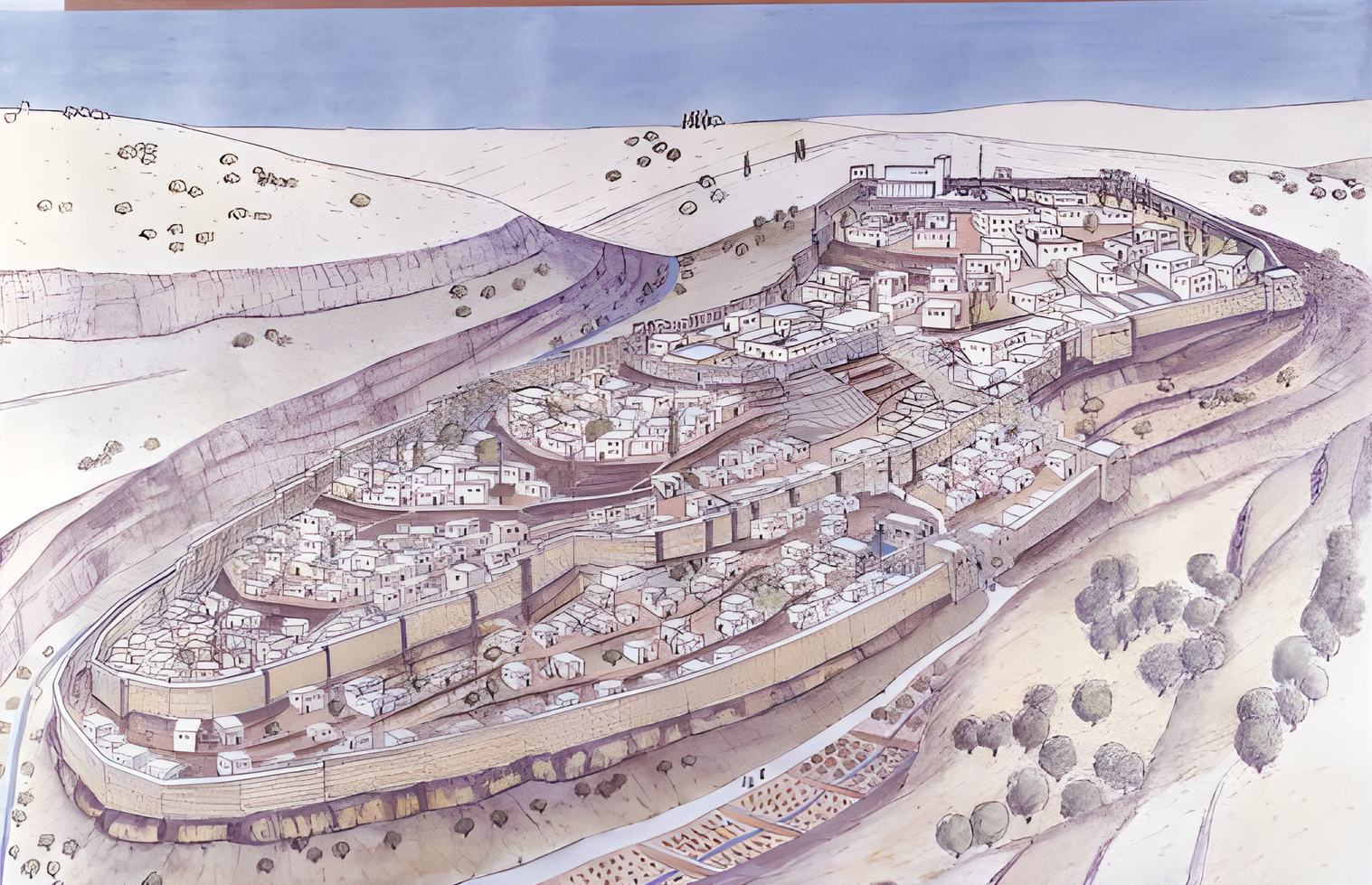

Lachish was a fortress city with a formidable array of defenses, and its capture would be no easy task. The city was built on a large mound, protected on three sides by natural wadis (dry river beds). It was ringed by two walls, each constructed of sturdy mud bricks on a stone surface. The upper wall was the main defense, roughly 18 feet thick and punctuated at intervals by tall towers.

Access to the city was via a low saddle of land that sloped up near its southwestern corner, but near the top any would-be intruder would encounter a massive fortified gate system. These fortified gates jutted out boldly at right angles from the main wall, looming directly above an entrance road that snaked up the saddle. The gatehouse boasted lofty towers, and no less than three chambers with heavy wooden doors.

Lumbering Siege Engines Like Ancient Tanks

But the Assyrians were masters of the siege, taking Lachish’s powerful defenses in stride. Wooden ramps were quickly assembled, platforms that would allow siege engines to approach the walls. At King Sennacherib’s signal, the siege engines lumbered up the ramps, leather-covered monstrosities that offered protection for both operators and defending archers behind their thick hides. The engines were propelled by the back-breaking exertions of Assyrian soldiers inside, wooden wheels creaking as they made slow but steady progress. Each siege engine also featured a long iron-tipped spear that functioned as a sort of battering ram.

The Judaean (or Judahite) defenders were not idle, and as the Assyrians approached, the air was filled with missiles of every description. Archers shot a steady stream of arrows, and slingers launched a deadly barrage of stones. When the Assyrian siege engines got close enough, defenders hurled lighted torches from the battlements, flaming brands that somersaulted through the air before colliding with the engines in a shower of sparks.

The torches were meant to set the siege engines alight, but the Assyrians were old hands at war and were prepared for every circumstance. By this time some ramps were covered with burning torches, a flaming carpet that threatened to immolate the advancing engines. Suddenly long-handled scoops nosed from each siege engine, giant ladles that were filled with water. When the water was poured out, the flames sputtered and died. Soon the air was filled with the acrid stench of smoke and burned wood.

Battering Rams Pound The Fortress Walls

The attack intensified, and as the siege engines neared the walls the defenders redoubled their missile fire. Clouds of arrows pelted down on the Assyrians, and here and there a black-bearded soldier would be pierced by a feathered shaft. Finally the siege engines were close enough to the wall to use their metal-tipped spear/battering rams. The rams swung back, then came forward with terrific force, each probing head biting into the mud-brick wall and gouging a deep hole in it.

Sennacherib watched the assault from a hill near the southwestern fortified gate. The man who grandiloquently styled himself “King of Assyria, King of the World” was seated on a throne, his feet resting on an elaborately decorated footstool. Two servants stood behind him with fans, shading and cooling the royal presence from the hot Judaean sun. He was dressed in a rich multicolor tunic bordered with gold fringe, and his long black beard hung down in ringlets. Sennacherib’s eyes gleamed in anticipation of the riches seized and the captives taken once the city fell.

Assyrian King Anticipates Waiting Plunder

The king was attended by the usual array of army officers and court functionaries, and nearby were some Assyrian artists taking careful notes. Sennacherib must have been pleased, because these artists were going to carve a series of reliefs commemorating the siege of Lachish. The reliefs would adorn a special room in the king’s palace at Nineveh, a place where Sennacherib could display the booty taken from the hapless city. Every detail of the siege had to be faithfully recorded, or the artists risked the king’s displeasure.

Sennacherib’s attention was diverted when a message came from King Hezekiah. The missive was one of total surrender; indeed, the Judaean king was almost groveling in his submission. Sennacherib had apparently sent troops to Jerusalem while he himself was investing Lachish. Hezekiah had few viable options; he found himself besieged in his own capital city, and his lands overrun. He was helpless and bereft of allies, who had been conquered or had submitted under threat of annihilation.

Hezekiah humbled himself before the might of Assyria, and in so doing saved his nation. “I have done wrong,” the Judaean king confessed, “withdraw from me, and whatever you impose on me I will bear” (2 Kings 18:14). Satisfied, Sennacherib agreed to withdraw—but made sure the peace would be a harsh one.

“Like a Bird in a Cage”

The Assyrian king afterward recorded his triumph on a stone later called the Sennacherib prism. “As to Hezikiah, the Jew, he did not submit to my yoke, I laid siege to his strong cities, walled forts, and countless small villages, and conquered them by means of well-stamped earth ramps and battering rams brought near the walls with an attack by foot soldiers.… Himself I made a prisoner in Jerusalem, his royal residence, like a bird in a cage….”

Once Hezekiah submitted, the Assyrian king goes on, “… I still increased the tribute and presents to me as overlord … Hezekiah himself did send me, later, to Nineveh, my lordly city, together with 30 talents of gold, 800 talents of silver, precious stones, antimony, large cuts of red stone, couches inlaid with ivory, nimedu-chairs inlaid with ivory, elephant hides, ebony wood, boxwood, and all kinds of valuable treasures, his own daughters and concubines….”

The Bible’s account of Hezekiah’s tribute differs in detail, not substance. In 2 Kings 18:14 we read that Sennacherib demanded three hundred talents of silver and 30 talents of gold. In today’s terms, that would still be 10 metric tons of silver and one metric ton of gold. In order to pay the tribute Hezekiah not only had to deplete his treasury, but strip even the gold ornamentation from the Temple.

A Divided Hebrew Kingdom

Hezekiah’s last-minute obeisance had won Judah a reprieve, but there was little time for rejoicing. The king had to consider his future course of action with great care. One misstep might mean the total extinction of Judah. Sennacherib’s campaign and Hezekiah’s subsequent submission came against a backdrop of intrigue and conquest that lasted more than a century.

Geography and faith have shaped the destiny of the people known to the Old Testament as Hebrews, or Jews to a later time. In the 10th century bc the 12 Tribes of Israel were united by King David and his son Solomon. After Solomon’s death ca. 933 bc the kingdom split apart into two mutually antagonistic states. The 10 northern tribes formed the kingdom of Israel, with its capital eventually at Samaria. Judah and Benjamin, the two southern tribes, stayed loyal to the House of David and formed the kingdom of Judah.

It was Israel and Judah’s misfortune to be in what scholars call the “Levant,” the coastal strip that borders the Mediterranean Sea roughly from Syria in the north to the fringes of Egypt. The coastal strip was a natural artery of trade and conquest, the crossroads of continents. Although possessing fertile lands, the Levant was also the gateway to Egypt, the “gift of the Nile,” whose fabulous wealth tempted aggressors for centuries.

Jerusalem Becomes Ground Zero For Jewish Worship

But if geography played an important role in Jewish history, so did faith. While most ancient cultures were polytheistic, worshiping a pantheon of gods, the Jews placed their faith in a single all-powerful deity called Yahweh. Whether called Yahweh, Jehovah or simply God, monotheism was the Jewish gift to the world. The state of Judah may have been small, but its capital was Jerusalem, the City of David. Jerusalem not only had political significance, it was the site of Solomon’s Temple, Yahweh’s house and the focal point of Jewish worship.

Both Judah and Israel had turbulent histories. Some pages of the Bible are filled with a grim chronicle of political strife, bloodshed, and religious apostasy. At times paganism was rife, and the people worshiped foreign gods and goddesses. Great prophets of Yahweh like Amos and Isaiah called them back to repentance, warning of dire consequences if they continued to stray.

While Judah and Israel were wracked with dissention and internecine strife, a new power was arising in the east, along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Assyria’s sturdy peasants made good soldiers, disciplined and brave, and the adoption of iron weapons made them formidable foes. Strong warrior kings provided the leadership to create an empire, one that soon encompassed much of the ancient Middle East. The Assyrians generally kept local native rulers in place, demanding only obedience and a steady flow of tribute from their conquered vassals. Sometimes, an Assyrian official was attached to a vassal’s court, just to keep an eye on things.

The Lost Tribes of Israel

In spite of political strife and occasional religious controversy, the 8th century bc was a period of general prosperity for both Israel and Judah. By this time both states were tributaries of the Assyrian empire, but Israel’s continued rebellion eventually brought retribution. In 722 bc the Israelite capital of Samaria fell after a long siege. Its capture marked the end of the Israelite state. Those not put to the sword or otherwise executed were deported to Assyria, there to disappear from the pages of history as the enigmatic “lost tribes of Israel.”

Starting with Tiglath Pilser III (744-727 bc), Assyrian kings sought a firmer control of the “motley of nations” that made up their disparate empire. Rebellion was ruthlessly crushed, often with wholesale slaughter followed by mass deportations. Rebels were tortured, and had to endure horrifying torments before being granted the mercy of death. Victims were impaled on stakes, beaten to death with iron bars, or even flayed alive. Terror became a weapon of Assyrian policy.

Conquered nations still hoped for freedom, patiently waiting for the chance to cast off the Assyrian yoke. Around 727 bc (dates are disputed) Hezekiah became King of Judah, and one of his first acts was to initiate a program of religious reform. His father Ahaz had been lax, with pagan cults to Baal and other deities flourishing throughout the land. The name “Hezekiah” means “Yahweh has strengthened,” and the new king proved it by demanding a return to the exclusive worship of Yahweh. Religious scruples aside, Hezekiah must have realized a return to Yahweh unified the nation in the face of coming trials.

Egypt In Decline Encourages Rebels In Levant

In 705 bc the Assyrian king Sargon II died, creating a temporary power vacuum while his son Sennacherib took over the reins of government. Scenting weakness, if only for a moment, many of the subject peoples raised the banner of revolt. Precise details are sketchy, but Judah apparently allied itself with the Philistine states of Ashkelon and Ekron, as well as Sidon in Phoenicia. The Ammonites, Moabites, and Edomites also joined the anti-Assyrian coalition, until it seemed nearly all the Levant was in revolt. Egypt encouraged the rebels, because its power was in decline and it rightly feared the power of Assyria.

Sennacherib had a reputation for cruelty and arrogance, but he was also a ruler of ability and political shrewdness. Judah and the other western tributary states were on the periphery, far from the centers of Assyrian power, as the king well recognized. Because they were far from the Assyrian heartland, they were of less immediate concern. He could deal with them in his own good time. Merdach-baladan of Babylonia was the greater threat, since he was much closer to Nineveh’s doorstep. A former ruler of Babylon, Merdach-baladan took advantage of the confusion attending Sargon’s death to regain control of the great city.

Prioritization of the Threat

The Assyrian king dealt with Merdach-baladan first, launching a devastating campaign that routed the Babylonian leader and sent him scurrying back into exile. Then Sennacherib turned north, stamping out “brush fire” revolts among the Median tribes along the Caspian Sea. These campaigns took two or three years, but by 701 bc the Assyrian king was ready to deal with the Levant. Sweeping down “like a wolf on the fold,” Sennacherib ravished the area with fire and sword. Sidon was taken, its king, Luli, fleeing from the city in terror only to find an ignominious death in exile.

The Assyrian army continued south, hugging the Mediterranean coast, and it seemed nothing could stand against it. The Philistine city of Ashkelon was captured, its king, Sidqa, put in chains. Turning north, Sennacherib attacked Ekron, which also was taken. Now, at last, it was Judah’s turn. In the Sennacherib Prism the king boasts of 46 Judaean cities taken, and 200,150 people led off into captivity, not to mention horses, mules, cattle, and other livestock. The figures might be inflated for propaganda purposes, but it was clear Judah had sustained a terrible blow, a blow that a less resilient people might not have survived.

Sennacherib accepted Hezekiah’s surrender, raised the siege, and returned to Nineveh in triumph. There is a current debate raging among scholars and archaeologists whether the 701 bc siege of Jerusalem was the city’s only brush with the Assyrians, or whether they returned a few years later. Recently uncovered evidence points to a second Assyrian siege, this one taking place perhaps ca. 688 bc.

Jerusalem’s Suburban Sprawl

King Hezekiah realized Jerusalem’s defenses had to be strengthened if the city stood any chance of resisting an Assyrian siege. The problem was compounded by the city’s growth, its population swelled by refugees coming in from conquered Israel. The matter once fueled another debate among scholars and archaeologists, but now it has been established that Jerusalem was expanding westward at a steady pace. Some authorities estimate Jerusalem covered 125 acres, maybe even more, and boasted a population of 25,000.

Time was of the essence; making Jerusalem ready to resist the Assyrians might take years to fully implement. Hezekiah dictated a flurry of orders to his scribes, and soon all Jerusalem was transformed into a hive of activity. Orders were inscribed on papyrus scrolls, then rolled up and tied with a string. The string was held in place by a small lump of clay called a bulla, which was imprinted with the king’s seal. Hezekiah’s seal bore the image of a winged beetle or scarab, together with the legend lhzqyhw ‘hdz mlk / yhdh, or “Belonging to Hezekiah, (son of) Ahaz, King of Judah.” Such a seal would command attention and immediate obedience.

A Tall Order: Shoring Up The City Walls

The walls of Jerusalem were one of the king’s chief concerns. The main city wall dated to 1700 bc, and in spite of repairs over the centuries it was in a delapidated condition. In any case, the old wall largely protected its ancient heart, the City of David. Jerusalem’s new growth to the west lay outside its boundaries. In 2 Chronicles 32 the Bible notes that “Hezekiah set to work resolutely and built up the entire wall that was broken down.” The king also ordered the construction of additional walls, including an outer wall that faced the Kidron valley to the east, and enclosed the Gihon Spring within its stone embrace.

The new and vulnerable western sections of the city also had to be protected by a wall, and work was begun at once. The new construction was massive, a broad belt of stone measuring 23 feet thick and about 27 feet high. Some residents found their homes in the path of these new walls, and had to yield “right of way.” A 210-foot section of this wall was discovered in 1969 by archaeologist Nahman Avigad, who dubbed it the Broad Wall. Isaiah notes in Isaiah 22:9-10, when speaking probably of Hezekiah, “You took note of the many breaches in the City of David [Jerusalem] and pulled houses down to fortify the wall.”

With the repair of the old wall and the raising of new ones well under way, Hezekiah could turn his attention to even more pressing matters. Water is crucial to human life, and an absolute necessity to a city resisting a long siege. Jerusalem’s only source of water was the Gihon Spring, located near the city gates. The cold, clear waters of the spring were funneled into a pool, which in turn was guarded by two or three towers. One of these, the Spring Tower, stood an impressive 30 feet high.

A Channeling Spring: An Engineering Marvel

Hezekiah’s workers restored and strengthened the towers, but the king and his advisers were still uneasy. True, the Gihon Spring and its pool now were protected by the new wall, and of course its looming stone towers. Yet Hezekiah was aware of a paradox: Those towers also were dead giveaways to an enemy, alerting him that something important was being protected. Worse still, the Gihon Spring and its pool were near the outer gates, traditionally a city’s most vulnerable point in time of siege.

The people of Jerusalem shared the king’s anxiety, saying, “Why should the kings of Assyria come and find water in abundance?” (2 Chronicles 32:5). Hezekiah and his officers began planning something that was bold and innovative: a tunnel that would channel Gihon’s water to the other, western, side of the city. It would be a major undertaking, as well as a brilliant piece of engineering for the 8th century bc.

Two teams of diggers were employed, each starting on opposite ends of the proposed excavation. It was hot, sweaty, back-breaking work, but when it was completed Hezekiah’s tunnel ran an impressive 1,750 feet. Water now flowed from the Gihon Spring to Siloam pool on the opposite end of the tunnel. If Sennacherib managed to breach the wall, and even capture the Gihon and its tower pool, Jerusalem would still not go thirsty. Since the tunnel entrance would be concealed, Sennacherib might never know waters still flowed to the other side of the city, safe from Assyrian control.

An Unlikely Ally In the Egyptian Pharoah

These projects would take years (another argument in favor of a second siege, because Hezekiah would simply not have had enough time to raise walls and excavate tunnels before the 701 bc assault). In any case, once preparations were complete the Judaean king could face the future with more confidence. Now, if he played his hand well, he might break the Assyrian chains that still held Judah captive. Looking for allies, he found one in Pharaoh Tirhakah, ruler of both Egypt and Ethiopia. Tirhakah, a general who gained the Egyptian throne in 690 bc, was apparently very lavish in his promises of aid. Hezekiah now had an earthly ally, but he was secure in the knowledge that Yahweh, the God of Israel, would also be on his side. The Judaean king now had the courage to again withhold tribute from the Assyrians.

Sennacherib’s reaction was one of predicable outrage. It was obvious that this upstart Jew and his petty hill kingdom needed to be taught a bitter lesson, a lesson that would also be salutary for other subject peoples straining at the yoke. Judah would be utterly destroyed, its lands laid waste and its people slaughtered or bundled off into captivity. No one knows what Sennacherib had in mind for Hezekiah, but it was probably torture, then execution by impaling or flaying alive. Perhaps Sennacherib was planning a special, even more gruesome method of execution, incensed as he was by Hezekiah’s continued defiance of his will. There was one thing for certain: The Judaean king was staking his own life and the life of his nation on a bold gamble.

Lachish Falls Harder the Second Time Around

If the two-campaign theory is correct, and evidence seems to point that way, Judah had 13 years to recuperate from the first Assyrian invasion. Now, the Assyrians were coming again, this time hoping to exact a terrible retribution. Once again Sennacherib swept down the Mediterranean coast, and once again Lachish was besieged. The Assyrians changed their tactics from their first attack on Lachish. This time they built one great siege ramp against the walls, instead of several smaller ones as they did in 701 bc. This great ramp was a difficult proposition, the task made more difficult by the incessant rain of arrows and stones coming down from the Lachish battlements.

But to the dismay of the Lachish population, the construction outside advanced. Then when the ramp was complete Sennacherib ordered a full-scale assault on the walls. Massive siege engine/battering rams lurched forward, sprayed as usual by accurate missile fire hurled from the battlements above. Soon Assyrian battering rams began to swing, colliding with the walls in a series of dull, rhythmic thuds. The Assyrian crews really put their backs into the effort, and deep fissures began to spread from the point of each impact. The walls could take no more, and soon much of Lachish’s southwestern wall collapsed with a roar.

It was a signal for the Assyrian infantry to move forward, clambering over the rubble of shattered wall bricks. With its powerful bulwark gone Lachish was helpless before the invaders, who swarmed through the city like angry furies. Those who tried to resist were ruthlessly cut down, until scores of bloodied corpses littered the narrow streets. The mound of Lachish was crowned by a huge palace-fort, which was probably the last to fall.

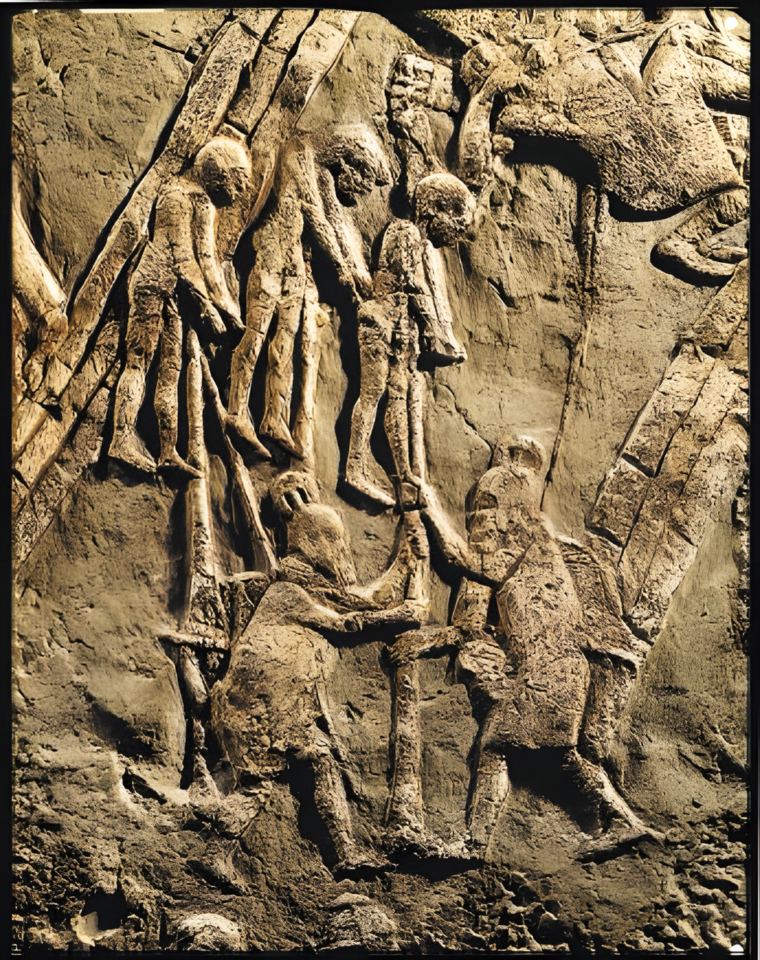

A Long March Of Pain And Sorrow

Their bloodlust sated, at least for the moment, bearded Assyrian spearmen began to gather booty and herd captives out of the city. Ordinary citizens were generally spared and ordered to gather up their belongings for the long march to Assyria. Some of the captives—perhaps the royal governor of Lachish and other prominent citizens—were singled out for special treatment. Dragged outside the city walls, they were stripped naked and impaled alive on long poles. Others were staked to the ground and flayed alive.

The survivors of Lachish began streaming out of their fallen city, a melancholy procession of involuntary immigrants facing life in a distant and alien land. Women carried sacks over their shoulders, all they could collect on such short notice, and as they trudged barefoot through the dust crying children clung to their tunics in bewilderment. The children’s mournful wails were a funeral dirge for a lost city. Judaean men led ox-drawn carts filled with possessions and family, prodded along by the bloody spears of watchful Assyrian guards.

The fear-numbed captives marched past the impaled victims, still writhing in agony atop their poles. A few were brought to Sennacherib himself, and once in the royal presence they flung themselves on the ground in supplication. No one could doubt but that Lachish was a kind of microcosm of Jerusalem, its fate a foretaste of what would happen to the capital of Judah if its defenses failed to repel the invader.

Jerusalem Braces For the Assyrian Assault

During the latter stages of the siege of Lachish, Sennacherib dispatched part of his army to Jerusalem. The Jerusalem-bound force was entrusted to a trio of top aides, the Tartan, the Rabsaris, and the Rabshakeh. The “Tartan” or “Tartanu” was an army officer, a kind of field marshal. Biblical scholars interpret “Rabsaris” and “Rabshakeh” in different ways. “Rabsaris” is translated “Chief of Eunuchs,” while “Rabshakeh” is rendered “chief butler,” “Chief of Staff,” or even “Vizier.” Whatever their designations, these men were no mere palace bureaucrats but skilled diplomats and subtle negotiators.

Meanwhile, messengers kept Hezekiah well informed about Assyrian movements. While Lachish still held the invaders at bay Jerusalem girded itself for battle. Stocks of grain were gathered from the countryside and placed inside the city. Peasant farmers and their families sought refuge within the city’s stout double walls. Men were issued spears and shields from the city’s well-stocked armories and assigned places on Jerusalem’s walls. High atop the battlements archers filled quivers with arrows, and slingers made mounds of stones that were placed nearby. Jerusalem’s great bronze-sheathed gates were ordered closed, and as they came together a heavy thud echoed over the gateway towers. The gates gave every impression of solidity and strength—but were they up to the fearsome pounding of an Assyrian battering ram?

Assyrian cavalrymen soon appeared, the vanguards of the main body. Then other Assyrian units began to arrive, and set to work pitching tents for a siege camp. The defenders must have been awestruck at the sight of the Assyrian army. The people of Jerusalem had had their own brief brush with the Assyrians during the first siege 13 years before, but now the enemy was here in earnest. Jerusalemites must have heard the stories of Assyrian conquest, of torture, death, and mutilation, and the tales grew in horror with each retelling.

Masters Of Psychological Warfare

The Assyrians knew their reputation preceded them, and in fact counted on it to weaken enemy resolve. While there might have been an element of sadism involved, Assyrians largely used slaughter, torture, and mutilation as instruments of policy. It was a not-too-subtle—yet effective—means of psychological warfare. There were other forms of psychological warfare as well, and the Assyrian commanders were about to try some of these techniques on the people of Jerusalem.

Chariots rumbled out of the Assyrian camp, the horses brightly caparisoned in red, blue, and gold. They halted just outside extreme bow-shot range and a herald asked for a parley. The Assyrians wanted to deal with Hezekiah himself, and demanded the royal presence. Hezekiah declined, but sent out three representatives instead: Eliakim, the head of the royal household; Shebnah, the palace secretary or scribe; and Joah, the herald.

When the opposing parties met it was the Rabshakeh who became the principal Assyrian spokesman. Fluent in Hebrew, he began a verbal offensive just as sharp as Assyrian spears. “Say to Hezekiah,” he began, “Thus says the great king, king of Assyria: On what do you base this confidence of yours? Do you think mere words are strategy and power for war? On whom do you rely, that you have rebelled against me? See, you are relying now on Egypt, that broken reed of a staff, which will pierce the hand of anyone who leans on it. Such is Pharaoh king of Egypt to all who rely on him” (2 Kings 18:19-21).

Hebrews Stand Defiant

No, the Rabshakeh continued, Egypt was weak, and the Judaean army pitifully small. The Rabshakeh even suggested, tongue in cheek, that Sennacherib would give Hezekiah two thousand horses—if, that is, the Judaean king could find riders for them. Up to this point the parley had been conducted in Hebrew, the Judaean language. The conference was held near the Gihon Spring, within earshot of the walls. The Judaean delegation respectfully requested that the talk switch to Aramaic, a lingua franca that was spreading throughout the Levant and was quickly becoming the language of diplomacy. Eliakim and his companions were understandably fearful that the Rabshakeh’s words would undermine the morale of the soldiers listening from the battlements above.

Taking his cue from the request, the Rabshakeh not only refused to switch to Aramaic, but actually began to address the soldiers on the wall directly, ignoring the official Judaean delegation. He stepped forward and called to the men on the battlements in a loud voice, couching his arguments in terms he thought would appeal to the survival instincts of the common people. “Do not let Hezekiah deceive you,” he cried in a loud voice, but the soldiers on the battlements maintained a stony silence.

The Rabshakeh urged the people of Jerusalem to make peace with Sennacherib. If they submitted, they would be spared and taken to “a land like your own, a land of grain and wine.”

The message was clear: Even if they surrendered, Jerusalem would be destroyed and they would be taken into captivity. Exile was hardly an enticing prospect, but the Rabshakeh seemed to feel that bondage in a foreign land was preferable to death. “Choose life, not death!” the Rabshakeh said in summation.

King’s Resolve Is Restored By Words From Prophet Isaiah

When the parley ended Eliakim and the others reported back to the king. The king’s resolve momentarily left him, and within moments he was plunged into paroxysms of grief and despair. Rending his clothes in token of distress, he soon replaced his royal robes with sackcloth and went to the Temple that his ancestor Solomon had built. The Temple was called the Bayit, literally the “House” of the Lord. Inside the Sanctuary there was the kodesh ha-kodashim, the “Holy of Holies,” where the sacred Ark of the Covenant was placed. While the king was absorbed in his devotions, his messengers sought out Isaiah the prophet. Isaiah sent words of comfort, saying the Assyrians would never take Jerusalem.

Meanwhile the Rabshakeh and his party returned to Sennacherib to make their report, finally catching up with him at Libnah. Flushed with victory, the Assyrian king’s arrogance was at its height. Sennacherib dispatched another message to Hezekiah warning him not to trust in the power of the Hebrew God. Other gods of other nations were unable to protect their peoples from the wrath of the Assyrians. Why, argued Sennacherib, should Yahweh be any different?

Assyrians Prepare For The Siege Of Jerusalem

Meanwhile, the defenders of Jerusalem watched in grim silence as the Assyrians made their final preparations to invest the isolated city. Brushwood was gathered in great quantities; this would be piled against the walls and set ablaze, so that the searing heat would crack the masonry. Mobile battering rams similar to the ones used so successfully at Lachish were readied and put into position. Assyrian sappers brought in tools to excavate earth, which would be used to build a great siege ramp. Sennacherib was apparently unaware of Hezekiah’s tunnel; earlier, the Rabshakeh warned the people of Jerusalem that their king was delivering them “over to a death of famine and thirst” (2 Chronicles 32:11). Little did the Assyrians know that the tunnel was already supplying a steady flow of fresh water to Siloam pool.

Would the new city defenses hold up to the fury of a full-scale attack? Luckily for Jerusalem, they were never put to the test, because something like a miracle occurred. According to Bible accounts an “Angel of the Lord” slew “185,000” Assyrians in their camp. There’s been much speculation about what happened, but poor sanitation—a common failing in ancient times—probably sparked an epidemic of some sort. Typhus or another disease must have spread through the Assyrians like wildfire, decimating their ranks and rendering the survivors weak and demoralized. There was nothing left to do under the circumstances but raise the siege and return home.

Jerusalem Spared According To the Prophet

The accounts aren’t clear, but Sennacherib apparently wasn’t with his Jerusalem army. Could it have been that the Assyrian king was elsewhere, busy fighting Pharaoh Tirhakah of Egypt? A recently deciphered Egyptian text claims a military victory by Tirhakah over an unnamed foe. Was it Sennacherib? If the Assyrians were defeated, or at least checked, perhaps Tirhakah wasn’t such a “broken reed of a staff” after all. Certainly, a possible defeat at the hands of the Egyptians, coupled with the Jerusalem disaster, would make Sennacherib’s campaign a shambles.

Assyrian defeat at the hands of the Egyptians is a matter for conjecture—but the Jerusalem debacle is a matter of historical fact. “So King Sennacherib of Assyria left, went home, and lived in Nineveh” (2 Kings 19:36). Thus runs a Bible passage that laconically records the end of the campaign. Yet there was no need for boastful words or rhetorical flourishes. Jerusalem had been delivered from the hands of Sennacherib, thanks in large part to Hezekiah’s preparations and—many believed—the intervention of Yahweh.

Sennacherib lived another seven years after the second siege, dying by the hands of two of his sons in 681 bc. He never returned to Judah, mute but eloquent testimony to the defeat he had sustained there. Isaiah’s prediction of Assyrian defeat had been fulfilled, as when he said, “Therefore, thus says the Lord concerning the king of Assyria, He shall not come into this city [Jerusalem] or shoot an arrow there, or come before it with a shield or cast up a siege mound against it. By the way he came, by the same he shall return, and he shall not come into this city, says the Lord” (Kings 19:32-33).

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments