By Robert Barr Smith

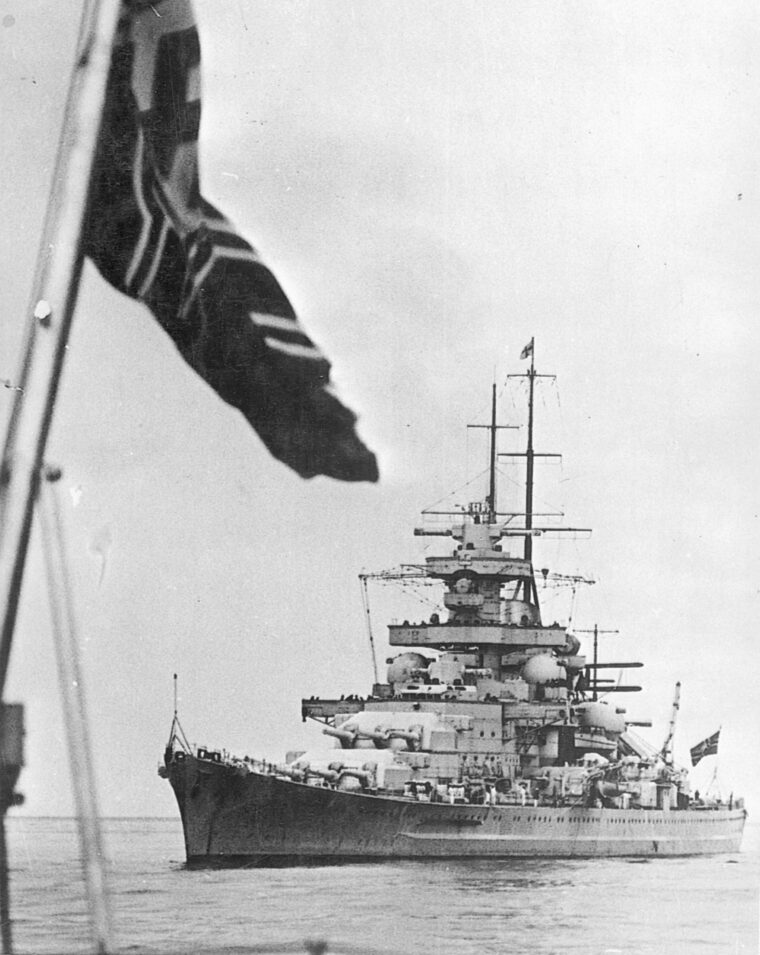

She was a beautiful ship, long and sleek and very fast. She was christened Scharnhorst,named for Prussian General Gerhard Scharnhorst,one of the revered founders of the Prussian Army. She could do more than 31 knots, she displaced almost 40,000 tons fully loaded, and she carried a complement of more than 1,900 officers and men. She was the ultimate commerce raider … at least in theory.

Scharnhorst carried nine 11-inch guns and a host of smaller weapons from 5.9-inch to 20mm. Her Krupp armor was as thick as 141/2 inches amidships and 14 inches around the barbettes of her big turrets. Her main battery was somewhat lighter than the 14- or 15-inch guns usually carried by battleships. Her builders, some said, had deliberately sacrificed a little gun power in trade for more speed and heavier armor; in fact, Adolf Hitler had decided to settle for 11-inch cannon to avoid arousing the suspicion of his European neighbors. The big ship’s main armament was to be upgraded to 15-inch at a later time … a time that would never come. Some debate still exists as to her appropriate classification as either a battleship or a battlecruiser.

Scharnhorst was sister to Gneisenau,also named for a Prussian general who, with General Scharnhorst,rejuvenated the dispirited Prussian Army in the latter days of the Napoleonic Wars. It is one of the many ironies of war that both Prussian commanders—in life men of liberal views—now lent their names and fame to ships flying the ugly black swastika of Nazi Germany. These fast battleships were not the first warships to bear these famous names: their predecessors, armored cruisers, were at the bottom of the South Atlantic, sunk by British men of war off the Falklands in 1914. By way of further irony, they had gone down under the command of Admiral Graf von Spee. His namesake, pocket battleship Graf Spee, was a scuttled heap of junk in the estuary of the River Plate, driven into Montevideo by the guns of Royal Navy cruisers in December 1939.

A Ship of Great Potential

If Scharnhorst was careful with her speed, she could cruise for 10,000 miles without refueling. With her great swiftness, substantial range, and heavy armament, she was the perfect commerce raider. She could run away from nearly any ship she could not sink, and she carried three seaplanes to spot her quarry for her. She and her sister ship, and pocket battleships Graf Spee, Admiral Scheer, and Deutschland(later renamed Lutzow), should have been a deadly scourge to the convoys so vital to the survival of Britain. Fortunately for the Allies, they were timidly employed by Nazi Germany. Compared to what they might have been, they were a miserable failure.

Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were laid down about the same time. Like her sister ship, Scharnhorst was begun in Wilhelmshaven in 1934. Gneisenau was completed in May 1938, Scharnhorst the following January.

Leaving the estuary of the Jade in November 1939, the two big ships came upon former P & O linerRawalpindiin the Iceland-Faroe passage of the North Atlantic.Rawalpindihad been converted to an armed merchant cruiser by the addition of a handful of 6-inch guns. Hopelessly outclassed, she nevertheless fought both German ships, hitting Scharnhorst with at least one 6-inch shell, causing casualties on her quarterdeck.

The end came quickly for Rawalpindi. As she burned like a blowtorch in the arctic darkness, the German ships were able to rescue a few of her crew. But upon the appearance of HMS Newcastle, a comparatively small 6-inch gun cruiser, both big German vessels ran for home under cover of smoke. They arrived safely, but the German command had demonstrated the persistent timidity—in sharp contrast to British dash and aggressiveness—that would plague their heavy ships throughout the war. The German Navy chief of staff, Admiral Kurt Fricke, registered the anger many German officers felt: “Battleships are supposed to shoot,” he wrote, “not lay smoke-screens!”

Both Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were at sea during Operation Nordmark, the abortive German reaction to British destroyer Cossack’s boarding of Altmark, the supply ship servicing the Graf Spee. Cossack had pushed boldly into an icy Norwegian fjord, putting a boarding party over the side in the old style, freeing some 400 British Merchant Navy prisoners taken by the raider. Neither Scharnhorst nor Gneisenau fired a shot during Nordmark, although they sortied as far as the Shetland Islands.

Renown Displayed Astonishing Firepower

During Weserubung (Weser exercise), the German invasion of Norway, the two ships traded shots with the British battlecruiser Renown. Gneisenau took a hit in the foretop, and both German ships turned away. Fighting in heavy seas, the Germans had great difficulty serving their main guns with any speed. Scharnhorst’s war diary recorded the ship’s frustration, and the impressive performance of their single adversary. “I found astonishing,” wrote a turret commander, “the high rate and continuity of the enemy’s fire, which was not impaired by the heavy movements of his ship.”

The engagement with Renown furnished further proof of the German crews’ lack of experience and training, and of the well-known tendency of both Kriegsmarine ships to be “wet,” shipping large quantities of water over their low freeboard and their bows, even after both ships had been refitted with graceful “Clipper 59” or “Atlantic” bows, intended to better parry the monstrous waves of the northern seas.

Still, Scharnhorst and her sister ship scored a major success by sinking homeward-bound aircraft carrier HMS Glorious—her decks crowded with RAF Hawker Hurricane and Gloster Gladiator fighter planes, flown off from Norway as the British and French withdrew. They also sank her two escorting destroyers, Ardent and Acasta. Before she went down in hopeless battle against the big ships, however, little Acasta’s captain, Commander C.E. Glasfurd, got a torpedo into Scharnhorst. Acasta sank not long afterward. In the finest tradition of the Royal Navy, Glasfurd stood on the bridge-wing smoking a final cigarette as his little ship went down. There was only a single survivor from Acasta.

Acasta had put the battleship out of action for many months. She would not be operational again until the autumn of 1940, for the little destroyer’s torpedo had torn a monstrous hole below the stern turret of Scharnhorst,rupturing a fuel tank and killing 48 of her crew. The British submarine Clyde torpedoed Gneisenau on June 20, and she joined her sister ship on the long list of German ships sunk or disabled during Weserubung. For all practical purposes, both ships would be out of action for the rest of the year.

The Antique Ship Begged for a Fight

In early 1941, both ships tried again, and this time came up with a British convoy. Again there was trouble for the Germans: The convoy escort included a battleship, HMS Ramillies. She was slow and relatively antique, a veteran of World War I, but she carried 15-inch guns and was spoiling for a fight. Scharnhorst tried to lure her away while Gneisenau struck at the merchant ships, but Ramillies was not having any of the Germans’ bluff. Both German ships, with all their modern armament and fire control, turned from one old battleship and ran for home.

In March the two big ships Savaged an unescorted convoy that was sailing empty on its way to Canada, sinking several ships. Later in the month, they closed in on still another convoy in the area of the Cape Verde Islands, only to find it escorted by battleship HMS Malaya. Malaya was another veteran, launched in the spring of 1915, but she packed 15-inch guns and substantial armor. Mindful of their orders and the pugnacious nature of the British, the two ships used their superior speed and turned away.

73 11-Inch Shells to Sink Her

Then, still in March, the Kriegsmarine managed a substantial success. Gneisenau and Scharnhorst got loose into the North Atlantic and there intercepted a number of freighters and tankers sailing independently after their westbound convoy had been dissolved. Between them, the two big ships sank 13 merchantmen and captured three others—two of which, with their German prize crews, were promptly recaptured by Renown. The only resistance to Scharnhorst and Gneisenau was a gutsy fight by the little freighter Chilean Reefer, which banged away at her two monstrous opponents with her one tiny deck gun. It took 73 11-inch shells to sink her.

The two German ships might have done even better, but once again they were interrupted by the approach of a single vessel, HMS Rodney, another veteran warship with a curious arrangement of three turrets forward and none aft. But the guns were 16-inch and Rodney was looking for a fight, and again the two modern German ships ran from a single older battleship.

In the summer of 1941, in La Pallice on the French coast, Scharnhorst was hit by five British bombs, requiring more repair in the port of Brest and causing further inaction. The German admiralty knew their two sleek ships would have to be moved, and early in 1942 occurred the famous “Channel Dash,” in which both ships successfully escaped up the Channel, first to Wilhelmshaven, then to Kiel in north Germany. On the way, Scharnhorst struck two mines off the Dutch coast, requiring still more repairs.

In February, however, a British air strike finished Gneisenau for good with a single bomb that tore through the two top decks and exploded. White-hot gas was sucked through the ventilation system and into the magazine of A turret, which went up with a colossal roar, killing more than a hundred seamen and leaving Gneisenau unfit for any offensive sortie. By early March, Scharnhorst was in Norway’s Altenfiord, in company with the super-battleship Tirpitz.

In September 1942, Scharnhorst sortied with Tirpitz and nine destroyers to destroy Norwegian installations on the remote island of Spitzbergen. While their big guns did a great deal of damage, Scharnhorst’s shooting was so bad that on her return to Altenfiord she put to sea again to improve her gunnery. In her absence, Royal Navy midget submarines sailed boldly into the fjord and crippled the mighty Tirpitz. The heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper had already been decommissioned after the bitter December day on which she, Lutzow, and six big destroyers had been driven away from a convoy by Royal Navy destroyers and two light cruisers. By the winter of 1943, Lutzow was gone from northern waters as well, sent to Gdynia in the Baltic for an overhaul.

Slow Merchant Ships Made Prime Targets

And on December 20, 1943, convoy JW55B set sail from Loch Ewe in far northwestern Scotland, 18 merchantmen bound for Russia through the bitter cold and vile weather of the Barents Sea. They were covered by a close escort, minesweeper Gleaner, destroyers Wrestler and Whitehall, and corvettes Honeysuckle and Oxslip. The destroyer escort—the outer ring of defense—comprised destroyers Onslow, Onslaught, Orwell, Scourge, Impulsive, Iroquois, Haida, and Huron. Captain James McCoy, in Onslow, commanded the escort.

Two days later, westbound convoy RA55A left Kola Inlet at Murmansk bound for Britain, its escort commanded by Captain Campbell on the destroyer Milne. RA55A, traveling unladen, slipped past the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe altogether, and by Christmas Day had left dreary, desolate Bear Island behind on its way to safety in Britain. Eastbound JW55B was not so fortunate. It was spotted by Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft as early as the 22nd. Loaded with military equipment and stores for the Russian juggernaut, the slow merchantmen were prime targets.

The British Admiralty, wary of a sortie from Norway by Scharnhorst,was prepared to provide heavy support if a major surface action developed. First there was the usual cruiser force, called Force 1, now waiting in Kola Inlet near Murmansk. In command was veteran arctic admiral Bob Burnett, one of the authors of the stinging defeat of Hipper, Lutzow, and their destroyers in the Barents Sea just a year before. Burnett’s flag was aboard the light cruiser Belfast, in company with her sister ship, the light cruiser Sheffield, and the heavy cruiser Norfolk.

British Sailors Rehearse for a Suspected Attack

Also at sea was Force 2: the battleship HMS Duke of York, escorted by the light cruiser Jamaica and four destroyers. Force 2 sailed from Akureyri in Iceland late on the 23rd. Aboard the 14-inch gun battleship, Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, commanding the Home Fleet, suspected a sortie by Scharnhorst might be in the wind, and he made plans accordingly. He had drilled his force in night tactics, and on the 24th even rehearsed an attack on Scharnhorst with Jamaica playing the role of the German warship.

Fraser also detached from the homeward-bound convoy a division of four fleet destroyers—Musketeer, Matchless, Opportune, and Virago—and sent them to join JW55B and strengthen the escort. Captain R.L. “Boggy” Fisher, in Matchless, commanded the division. For his part, Fraser sailed northeast, setting course to cut the German battleship off from Norway if she came out, as he expected, to attack the Russia-bound convoy. On the 24th, he signaled Captain J.W. McCoy, commanding the convoy, to reverse course for three hours, allowing Fraser more time to close in on the vulnerable merchantmen and their escorts. Since the convoy was already behind schedule, McCoy achieved the same end simply by further reducing speed.

Christmas at sea was no holiday for either the Royal Navy or the crews of the weathered merchant ships. Even an alteration of course could cause major shifting in the freighters’ deck cargo, or a loss of their boats. Hammered by gale-force winds and monstrous seas, the crews, especially those of the little escort vessels, had no chance for a decent meal; as their battered ships pitched and yawed in the howling perpetual night of 73 degrees north latitude, the crews made do with mugs of hot tea and cocoa, sandwiches, and whatever other meager fare the galleys could provide.

Back in Altenfiord, on the northwest coast of Norway, Scharnhorst was indeed preparing for sea. Lying at anchor in relative peace, her crew had decorated the ship with little fir trees for the Christmas holiday, eaten well, and sung their Christmas songs; now they were preparing to fight.

Admiral Erich Bey, temporarily commanding at Altenfiord, would take five destroyers with him into the winter wilderness of the Barents Sea: Z29, Z30, Z33, Z34, and Z38. These ships were all of the so-called “Narvik flotilla,” and carried four 5-inch guns plus torpedo tubes and antiaircraft armament. They displaced between 1,800 and 1,900 tons. They were fast and well armed, but they lacked the excellent sea-keeping qualities of British destroyers.

Bey was a fine seaman, a big officer popular with his men, survivor of the Norwegian massacre of German destroyers by the Royal Navy in 1940. A destroyer officer, he had not commanded any ship the size of Scharnhorst,but he had capable help in Captain Julius Hinze, who would actually command the battleship. On board Scharnhorst were 1,968 officers and men, including more than 40 officer cadets. With a number of personnel on leave, Bey drafted from crippled Tirpitz replacements for absent officers and key enlisted men.

“The Attack Must Not End in Stalemate”

The operation against the British convoy was dubbed Ostfront 1700. The coded signal directing it ordered Bey to intercept the convoy on December 26, at first light—about 10 o’clock in those wild waters in that miserable month. Bey was reminded—as if he needed reminding—that the British enemy was “trying to hamper the heroic endeavors of our eastern armies by sending a valuable convoy of arms and food to the Russians. We must help.”

His orders further directed that “the tactical situation must be exploited with skill and daring and the attack must not end in stalemate. Every opportunity to attack must be seized using the Scharnhorst’s superiority to the best advantage….” But then came the usual dismal cautionary instruction: “You must disengage if a superior enemy is encountered.”

German naval intelligence had lost track of powerful Duke of York and her escorting destroyers, but the Germans did not find their lack of information worrisome. Apparently their intelligence analysts believed Fraser’s force had accompanied the empty convoy back to Britain. In any case, they thought, even if Fraser had not returned to the Royal Navy anchorage at Scapa Flow, Scotland, his ships were probably too low on fuel to remain in the Barents Sea and fight. They were wrong on both counts.

Even the usually reliable German B-Dienst,the radio-intercept service, had been wrestling with a series of British transmissions that they could not decipher. The B-Dienst analysts guessed, however, that the traffic might indicate the possibility of a “heavy covering force [heading] toward the target”; the target, of course, was the convoy. However, the German headquarters at Navy Group North then decided the report was insufficiently reliable to pass on to Bey at sea. The error would have tragic consequences for a great ship and her crew.

Admiral Fraser now had confirmation that the Germans were coming out. The British were utilizing their Ultra capabilities to read German radio traffic encoded by their Enigma machine, and the Admiralty had radioed Fraser that a British agent had seen the big ship leave Altenfiord. Bey had no such hard information.

U-Boats Forced to go Too Deep To Fire Torpedoes

He was dependent on Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft, supposedly covering an area of some 300 miles around the convoy, watching for any Royal Navy covering force. He would also have the dubious aid of U-boat surveillance by the boats of Gruppe Eisenbart (Ironbeard), which would report what little they could see through the enormous swells, snow squalls, and driving rain of the Barents Sea. U-boats and shadowing aircraft were able to keep track of the progress of the convoy, although British escort vessels drove U-boats deep time and again, and at least kept them from using their torpedoes.

Most important, both submarines and aircraft failed to find Duke of York and her consorts. Fraser was coming up fast from the west, and the Germans did not know he was there. The weather had turned vile, as it usually was in these latitudes at this time of year. The winds were force 8 from the south, gale-force, driving, mountainous seas. Visibility was generally down around two to four nautical miles, depending on the intensity of the overcast, the flurries of snow, and the sheets of bitter rain that whipped through the almost perpetual night of this desolation.

The German destroyers, less seaworthy than their British counterparts, were already having great difficulty, and Bey signaled Dönitz, asking whether the operation should continue. Yes, answered the admiral, although he did give his commander at sea permission to carry on with Scharnhorst alone, at his discretion.

And so, by 0400 on the morning after Christmas, St. Stephen’s Day, Scharnhorst and her destroyers were steaming north to intercept the convoy. Burnett’s cruisers—about 150 miles away from the convoy—were sailing in from the east, and Fraser was bringing Force 1 eastward to get across Bey’s line of retreat to Norway. Westbound convoy RA55A was already some 200 miles west of dreary, desolate, fog-shrouded Bear Island, and apparently still undetected by the Germans. It was out of danger.

JW55B was south of Bear Island about 50 miles, making a glacial eight knots in the foul weather. It was very much in harm’s way. The weather was delaying Admiral Fraser, too. He was forced to hold his group’s speed down to around 24 knots, to save his destroyers from broaching-to in the huge seas and a southwesterly wind howling in at 50 knots. They were having, to quote Fraser’s flag captain, “a hell of a time of it in this sea.” The waves were so bad that even big Duke of York steadily buried her bow in the swells; water was pouring down her ventilation ducting into the spaces below.

If Admiral Fraser could lure Scharnhorst far enough to the north, away from safety, and if Burnett’s cruisers could intercept and delay her, Duke of York might catch the German ship and put an end to her. Fraser signaled Captain McCoy to swing his convoy to the northeast, away from the German threat, and ordered Admiral Burnett to close up to the vital convoy.

The End for Scharnhorst?

By 0700 the British knew contact had to be imminent. Belfast came to First Degree Readiness at about 0700. Aboard Scharnhorst Admiral Bey, sure he was close to the convoy, went to Action Stations a half-hour later. At about 0800 Bey received a message from a U-boat, from which the German admiral determined he had probably passed ahead of the convoy. Accordingly, he ordered his destroyers to shake out into a picket line some 10 miles ahead of the battleship, keeping station about five miles apart. The smaller ships apparently got only part of Bey’s signal, or read it wrong, for they began their sweep of an area not intended by Bey and lost contact with Scharnhorst … as it turned out, forever.

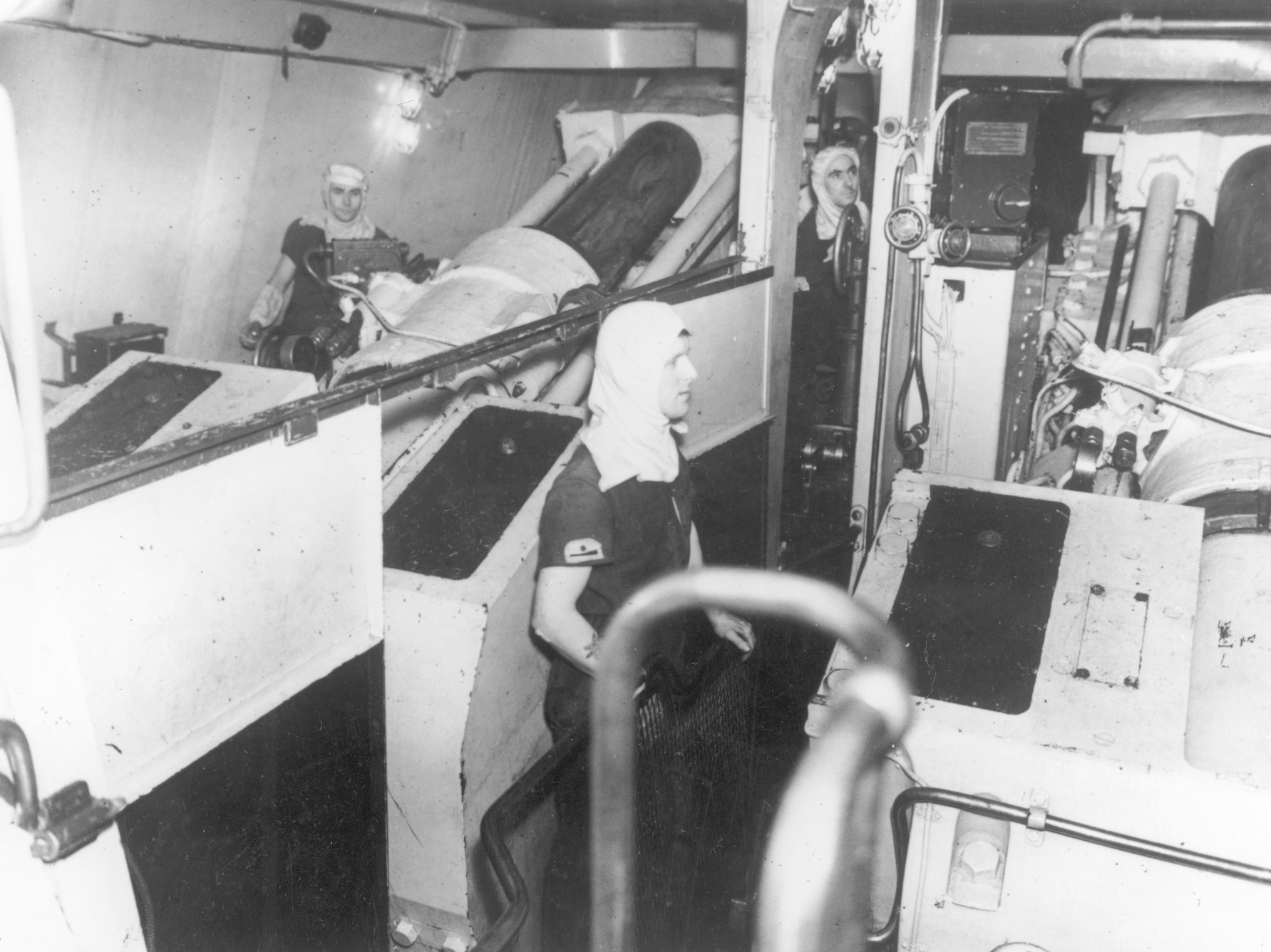

At about 0830, Sheffield came to Action Stations. Burnett’s cruisers, moving roughly northwest, were now approaching Bey’s force at right angles, or nearly so. Antiflash hoods pulled over their heads, the gun crews waited by their tubes. The officers’ wardroom was laid out for use as an operating room. High up in the cruisers’ superstructures the men at the directors squinted into their gunsights. The ready-lights glowed: All guns were loaded and ready to shoot. Overhead the huge white and red battle ensigns streamed in the gale.

At 0834, Norfolk’s radar picked up a contact at last, a little over 17 miles away through the gloom to the west-northwest. Belfast’s radar found the same blip moments later, and Burnett radioed that he had found the enemy. With the convoy, Captain McCoy on Onslow heard the report. On Admiral Fraser’s order, McCoy detached the four destroyers acquired from the homeward-bound convoy and sent them racing to form a skirmish line between the convoy and its enemy. As the range decreased, British lookouts peered through the gloom, trying to acquire visual contact with the enemy.

Not until 0930, still night in this arctic December, did the vague shadow of Scharnhorst appear to Sheffield’s lookouts, distant about 13,000 yards. From Belfast, British starshells burst in the gloom overhead, shedding a weird pinkish light over the wild sea. There she was, sleek and menacing amid the dark heaving seas, and the cruisers opened fire. The onslaught came as a complete surprise to Bey. Neither of his radar sets had spotted the British cruisers, and the Royal Navy’s gunnery was excellent. An 8-inch shell from Norfolk tore Scharnhorst’s fore-top apart, left behind a pile of dead and wounded seamen, smashed the gunnery director that controlled the forward port 5.9-inch guns, and turned the forward radar antenna into junk. Another shell slammed into her forecastle moments later, and still a third landed between a port gun turret and the battleship’s torpedo tubes. With his cruisers engaged, Admiral Fraser now ordered Captain McCoy to turn the convoy onto a northerly course, out of harm’s way.

Scharnhorst was unable to spot either of the light cruisers, since both were using flashless cordite powder; all Bey could see was the flare of muzzle flashes from Norfolk, not yet equipped with the new propellant. Surprised, his ship hurt, Bey turned away to the southeast. Much faster than the cruisers in these heavy seas, Scharnhorst pulled away. Steaming out of effective gunfire range, she would soon be beyond radar contact.

Burnett’s Bold Decision

At this point in the engagement, Admiral Burnett made a command decision, a bold, well-reasoned choice that would control the course of the entire action. Perceiving that his quarry was edging around, turning first east and then northeast, Burnett correctly decided that Scharnhorst was trying to work around him to try again to strike the convoy. “Ah!” he said. “So she’s not running for Alten Fjord after all … well, we’ll take the short cut.” Acting on his conclusion, he broke off his pursuit and turned back again to the northwest, sailing to join the convoy and stay between it and the raider.

Duke of York, Jamaica, and their destroyers were still almost 200 miles away to the west. Fraser had made the difficult decision to press on to the east, even though his destroyers were dangerously low on fuel. Burnett’s cruisers, two of them armed only with 6-inch guns, would have to fight the big ship alone until help arrived.

Imperturbable Bob Burnett was no stranger to this kind of work: A year before, with two light cruisers and a handful of destroyers, he had driven away heavy cruiser Hipper, pocket battleship Lutzow, and six big destroyers from a hard-pressed convoy in these very waters. Now he led his ships north to join the convoy; he was deliberately breaking radar contact with Scharnhorst,convinced he knew where the German ship was going. He was entirely correct.

Meanwhile, Scharnhorst plowed on to the northeast. Bey had lost all contact with his destroyers during the engagement with Burnett’s cruisers. Now he radioed them to turn back to the north at high speed and rejoin the big ship. They complied, but by now they were so far separated from Bey that they could not catch up; they would never see Scharnhorst again.

For the rest of the morning, as a dim, dreary imitation of daylight marginally brightened the blackness of arctic December, Scharnhorst pushed on northward, looking for the merchantmen. Burnett had joined the convoy, as had the four destroyers detached from the homeward-bound convoy. Led by Commander Fisher in Musketeer, the little ships fought through the waves ahead of Burnett’s cruisers, themselves sailing some 10 miles ahead of the convoy.

Bey had received a message from German scouting aircraft that had spotted Fraser’s force. The Luftwaffe had correctly identified one heavy unit as part of the British force, even though its position, as reported, was 50 miles in error. As the signal came to Scharnhorst, however, it made no mention that a British heavy unit was part of the force the aircraft had seen. Bey pressed on; if he had misgivings, he had also received the message from Dönitz, somewhat stridently urging him to “strike a blow for the gallant troops on the eastern front by destroying the convoy.”

Knowing They Might Explode at Any Moment, Hardy Removed the Powder Charges

A little before noon, McCoy ordered the convoy to alter course toward the southeast. As the convoy complied with the complicated maneuver, the radar operator on board Belfast reported a contact. It was Scharnhorst,coming from the northeast. Just before 12:30 all of Burnett’s cruisers opened fire at a range of about 10,000 yards, again lighting up the arctic gloom with starshell. The German ship immediately turned northwest, firing her 11-inch guns at her tormentors. She concentrated her fire on Norfolk, the best target because of the visible flash of her broadsides.

Scharnhorst hit Norfolk twice. One of the big shells disabled X turret (the rearmost); a second started a formidable fire amidships, but the cruiser pressed on, her speed unaffected. In the ruins of X turret, surrounded by the dead, Marine C.G. Hardy was methodically removing powder charges from the gun-rammers although he knew he might be blown to bits at any second; the ship came first. Hardy’s heroism would win him the Distinguished Service Medal.

During the exchange of fire, shells from all three British ships struck Scharnhorst—Belfast hitting the big ship seven times. The British destroyers added their own lighter broadsides and tried hard to close in to attack with torpedoes. As the German ship smashed through the wild seas at 28 knots, the destroyers could not catch her.

Bey had had enough. Those dogged British cruisers were between him and the convoy and obviously proposed to stay there; it was time to go home. He turned away, and at about 1400 he signaled his lost destroyers to do the same. They complied, although without knowing it they were less than 10 miles west of the convoy when Bey’s signal was received. Now, as Bey raced for safety in Norway, Burnett’s ships shadowed him, lurking behind him and watching the Germans with their radar. Visibility was decreasing from bad to worse, low stratus clouds and wind-driven spume adding to the gloom.

Scharnhorst’s crew now had a chance to eat. Details carried buckets of hot soup and big chunks of bread from the galley to duty stations all over the ship. The British ships were behind them now, and falling ever farther back. There was no firing, and the ship was racing for home. It must have seemed to the German sailors that the mission was over—safety was less than 200 miles away. On the bridge, Bey and Hinze were not so sure. The British were still tracking them, and they must have wondered if their enemy had some ugly surprise waiting for them. At about 1645 they would find out.

The chase was difficult for Burnett’s cruisers. Sheffield lost a shaft bearing and was forced to drastically reduce speed while repairs were made. Norfolk also had to temporarily reduce speed while she fought the fire caused by one of Scharnhorst’s shells, leaving Belfast and the destroyers to shadow Scharnhorst. Behind them the crews of Sheffield and Norfolk worked frantically to get back to speed and rejoin Belfast. If Scharnhorst were to turn on that single light cruiser now … but she did not. Bey was running for home. The cruisers had done their job and done it very well indeed. Bey, though he could not know it, was well into the trap. Fraser’s tactics had worked perfectly, and he was now close enough to get across Scharnhorst’s path to safety.

Setting the Stage for Battle

Fraser knew he was close to his quarry, closing in on Scharnhorst at about right angles to the German’s course. Fraser had split his four destroyers into two divisions, two little ships on each bow of Duke of York. Now, at 1632, as the anemic northern daylight faded, his radar operators reported contact up ahead. It was more than 45,000 yards away … and it was Scharnhorst. At last Fraser could come to grips with Germany’s last seaworthy capital ship, but he had to be careful. Scharnhorst was faster than any ship in the British stable. If Duke of York or the cruisers could not hit her hard enough to slow her down, she might still escape into the gloom of the arctic night.

As Fraser’s force closed in on Scharnhorst,Norfolk, her fire now under control, was catching up with Belfast. Sheffield still trailed her two sisters, even though she had been able to get her speed back up to 23 knots. Flanking the cruisers on the west were Virago, Opportune, Matchless, and Musketeer. Duke of York, trailed by Jamaica, was led by Savage and Saumarez on her port bow, and Scorpion and Stord to starboard. The stage was set.

Bey did not know he was under attack until that sickly pinkish glare again shattered the darkness above him, and monstrous waterspouts rose all around his racing ship. Duke of York and Jamaica had begun to shoot, opening fire at about six miles through swirling rain and snow, and their gunnery was superb.

Duke of York’s very first salvo straddled the German ship, and one of the 1,400-pound shells struck home, crashing into Scharnhorst’s A (Anton) turret—the one closest to the bow. Minutes later a second 14-inch projectile smashed onto the quarterdeck, causing heavy damage. Jamaica hit Scharnhorst with her third salvo. The hit on Anton turret set fires that quickly spread aft to Bruno turret, and Scharnhorst’s skipper partially flooded the powder-handling room to prevent an explosion. Although the fire was controlled and the powder room drained within minutes, A turret was finished. Then Duke of York scored again, a hit aft that set more fires. The shock of the big guns knocked Duke of York’s bridge clock loose, coming very close to the admiral’s head in its fall. It is not recorded that Fraser minded at all.

Scharnhorst’s superior speed, 31 knots, began to open the range, and two of her shells tore through Duke of York’s masts without exploding. One round cut through all the battleship’s radio antennas and severed the wires leading to her gunnery-control radar. In spite of the wild sea and terrible weather, a Royal Navy reserve lieutenant named H.R.K. Bates managed to climb the wet, swaying mast in the screaming wind and make repairs. Clinging to the mast in the darkness, shaken by the battleship’s thunderous broadsides, working with numb hands, he got the vital gunnery radar up and running again.

More than 40 Salvos Fired

Fraser’s destroyers, pitching and yawing terribly in the monstrous seas, tried desperately to gain enough to attack the German leviathan with torpedoes. Running light—they had used most of their fuel—and in constant danger of broaching-to from huge following seas, Savage and Saumarez tried to close in on the German’s port side; Scorpion and Stord struggled to reach attack positions to starboard. Off to the north, Musketeer led her three destroyers on a course parallel with that of Scharnhorst’s.

Just before 1700, the guns of Belfast and Norfolk joined in, and both Force 1 and Force 2 chased Scharnhorst to the east. Duke of York continued to hit the German ship.

Scharnhorst’s twisting course made Duke of York’s gunnery very difficult. Even so, by 1820 Duke of York had fired more than 40 salvos and straddled her rapidly moving quarry with more than 30 of them. Still, even as the destroyers gained on Scharnhorst with terrible slowness, big Duke of York was gradually losing ground to the speedier German vessel. For all his careful planning and his ship’s good shooting, Fraser knew he still might lose his quarry.

And then, at 1840, Duke of York’s guns found Scharnhorst again and hit her hard. This time British shells took out Bruno, the second forward turret, and also hit Scharnhorst below the waterline. A shell tore into number one boiler room, cutting a steam line, and Scharnhorst’s speed dropped off to about 10 knots. Although heroic work by the German engineers got her quickly back to 22 knots, Duke of York and the destroyers now began to overtake her rapidly.

Scharnhorst’s superstructure was twisted junk by now, and the ship was littered with dead men. Wounded were everywhere, and writhing men terribly scalded by steam lay on the decks far below. She had lost two-thirds of her main armament and several 5.9-inch turrets. Still, her speed was now back, and she was again pulling away from the British. At 1830, Hinze got on his intercom and complimented his crew, but his congratulations were premature. Only a few minutes later four British destroyers appeared out of the murk, two on each flank of Scharnhorst,making 30 knots in spite of the tumultuous seas.

Savage and Saumarez closed in first, cutting the range down to 10,000 yards, their guns repeatedly hitting Scharnhorst’s massive superstructure without damage from the ineffective 5.9-inch secondary armament of Scharnhorst. And now, from the other flank, Scorpion and Stord were attacking unobserved. As Scharnhorst turned south Scorpion and Stord fired 16 torpedoes at a range of about a mile. One struck home.

11 Dead, 11 Wounded

Under the unearthly light of starshells, Savage and Saumarez closed in to launch their own torpedoes. Between them, the two little ships got three torpedoes into Scharnhorst. Saumarez, however, was hit by several 11-inch shells, and two big rounds took out her fire- director and range-finder. Her luck was in, however, for neither shell exploded. Other big rounds did explode in the water near her, sweeping her decks with clouds of steel splinters, puncturing her hull, and leaving 11 of her crew dead and 11 more wounded. Her speed reduced to 10 knots, the destroyer made smoke and turned away. But one of her deadly fish had struck home.

At 1901, Duke of York and Jamaica, which had ceased fire during the destroyer attacks, again opened fire at about 10,000 yards, almost point-blank range for their guns. They hit the German ship again and again, Duke of York straddling her with her first salvo and hitting her with the second, starting huge fires aft. On Scharnhorst the crew was moving 11-inch ammunition aft to C turret, the ship’s only operational big guns. Ten minutes later that turret was also put out of action, perhaps by two successive hits from Belfast’s guns. Scharnhorst was listing now, and the massive fires had overwhelmed her damage-control parties. Belfast and Jamaica launched their own torpedoes and scored two more hits on the dying giant. In the wild arctic darkness, Scharnhorst blazed with fires, and her speed fell away to a bare 5 knots. Bey knew his ship was finished and signaled the German admiralty that Scharnhorst would “fight to the last shell.”

Now it was Commander R.L. “Boggy” Fisher’s turn with his wildly pitching Musketeer and her three weather-beaten consorts, after a long chase through wild seas. At the start of it, he had shouted to his torpedo officer, “We’ll have a shot at torpedoing the bastard if we can get near enough!” “Aye-aye, sir!” came the reply from that officer, poised by the torpedo-sight on the destroyer’s bridge. Now their moment had come. Musketeer and Matchless could also use their 4.7-inch guns enclosed in turrets; Opportune and Virago, with their older open gun mounts, could not.

Between them, Musketeer, Opportune, Virago, and Matchless hit the German ship with six more torpedoes. There was nothing to be seen of Scharnhorst now but a thick smoke cloud with a hideous evil glow inside it, like coals in the heart of a blacksmith’s forge. At 1945, as Belfast closed in to launch more torpedoes, a monstrous underwater explosion shook the wild sea, and the glow disappeared into blackness. It was over.

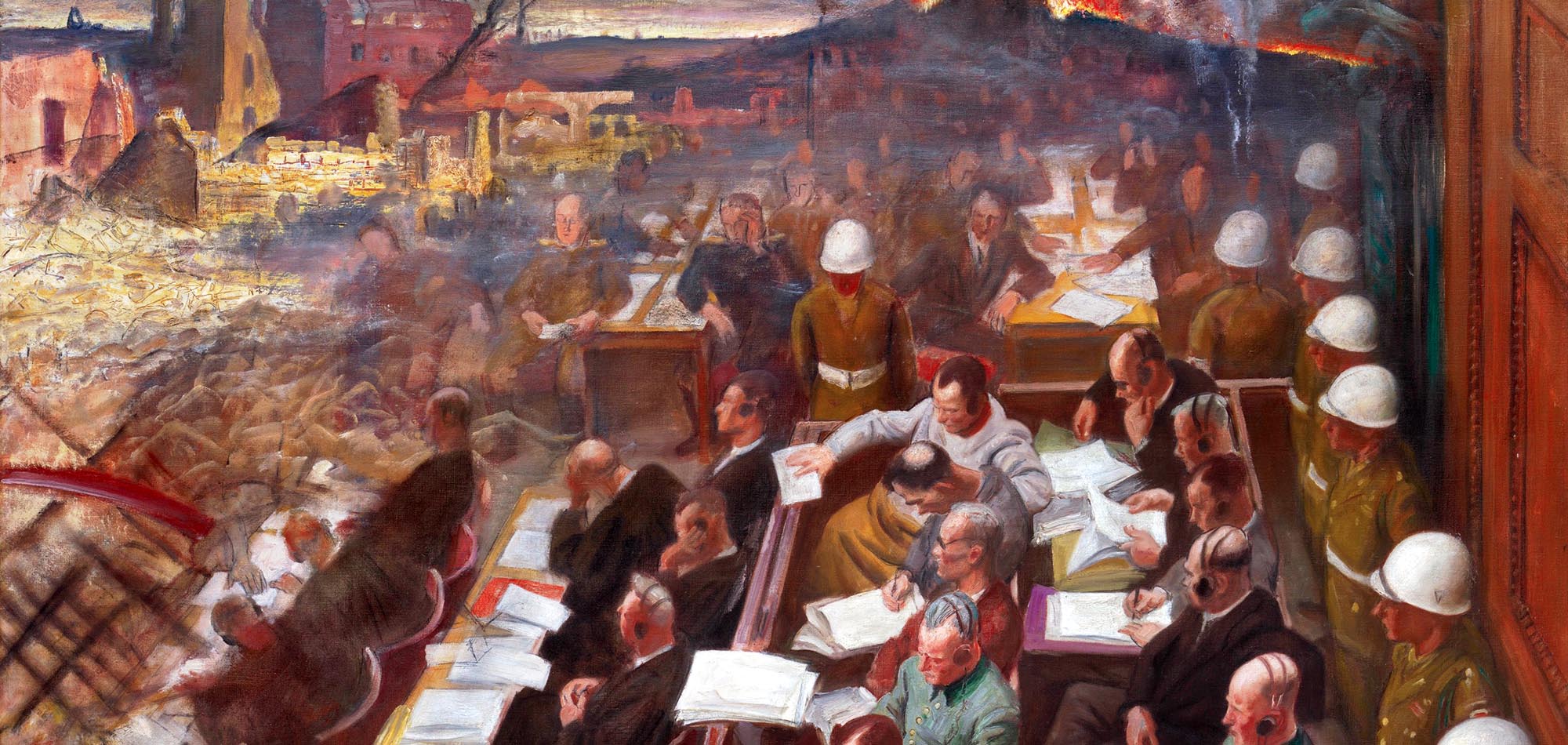

Sinking the Scharnhorst

The destroyers, and Belfast and Norfolk, did what they could to collect survivors from the bitter cold of the Barents Sea. They could find only 36 living men in the frigid darkness, some of them singing in the night: On a sailor’s grave no roses bloom. The others, over 1,900 of them, were gone with their ship 150 fathoms down. Neither Admiral Bey, Captain Hinze nor any of the other officers were among the survivors. Hinze was spotted, but in the bitter cold he could not hold on to a lifeline long enough to be hauled to safety.

Admiral Fraser called Burnett on the TBS—talk between ships—rarely used at sea for security reasons. “Well done, Bob,” he said in the clear, and then he turned to his officers on the bridge. “I think we may secure from Action Stations. It’s unlikely that we shall be worried again tonight.”

Scharnhorst’s protracted death struggle was a testament to her design and construction. She had absorbed 11 torpedoes, at least 13 hits from Duke of York’s 14-inchers, 10 or 12 more 8-inch shells, and a great many rounds from the smaller guns of the light cruisers and the destroyers.

For the Allies, with the sinking of Scharnhorst the convoy routes to Russia were at last rid of the long-time threat from Germany’s battleships. The battle against the U-boats was not over, but the Royal Navy was winning that fight, too. Many of the British Home Fleet’s big ships were now free for employment on other missions.

The death of Scharnhorst was the final nail in the coffin of the German surface navy.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments