By Michael D. Hull

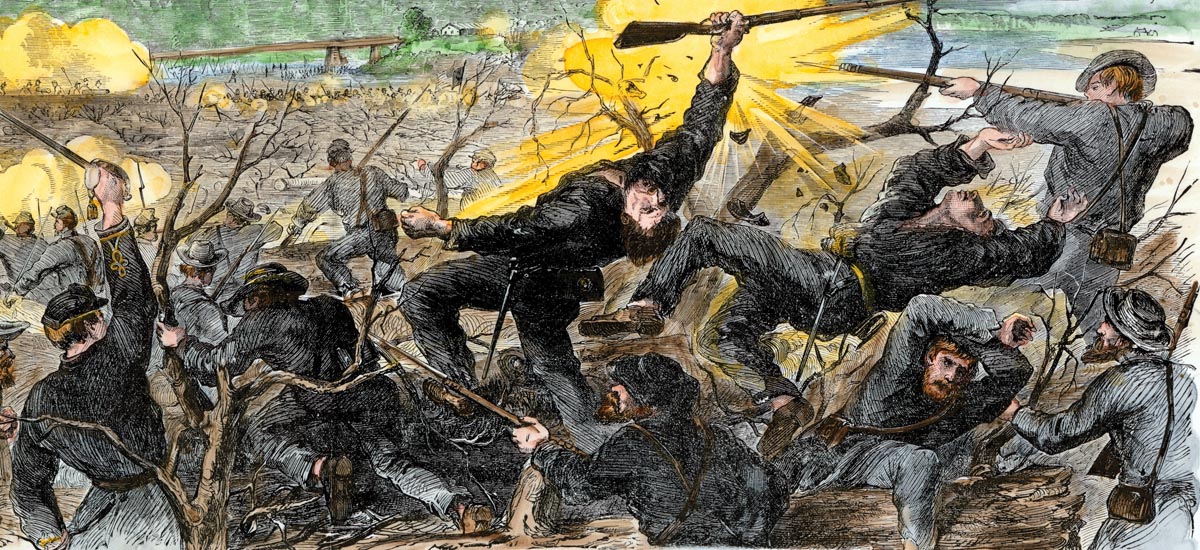

Still stunned by the sneak Japanese onslaught on the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, American families tried to summon up their Christmas spirit in December 1941. More than 60 years ago, Americans approached their first yuletide in World War II stoically, hanging up stockings above fireplaces, pinning evergreen wreaths to front doors, and placing Christmas trees on front lawns and town greens.

Subdued Christmas Celebration Post-Pearl Harbor

As their country moved, hesitantly but with increasing dynamism, into the global struggle against fascism, families whose fathers, sons, and brothers were in uniform—or soon would be—tried to make Christmas 1941 a time to remember; a blessed if brief interlude in a grim era. No one knew what lay ahead.

At the White House, it would prove to be a strange though historic Christmas. None of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s children or grandchildren would be there; all of the Roosevelt sons were in uniform elsewhere, and daughter Anna remained with her husband and children in their Seattle home. On the White House fireplace, only two Christmas stockings were hung—one for little Diana Hopkins, daughter of presidential adviser Harry Hopkins, and one for the president’s Scottie dog, Fala. In previous years, a dozen or more had been hung there.

FDR Prepares For Visit From a Special Guest

The gregarious President Roosevelt would miss being surrounded by the large, boisterous family he loved. Nevertheless, as he toiled with characteristic calm to place his woefully unprepared nation on a war footing, FDR looked forward to welcoming a special guest, Prime Minister Winston Churchill of Great Britain.

In a December 9 message to Roosevelt, Churchill had asked, “Now that we are, as you say, ‘in the same boat,’ would it not be wise for us to have another conference? We could review the whole war plan in the light of reality and new facts, as well as production and distribution. I feel that all these matters, some of which are causing me concern, can best be settled on the highest executive level.”

Great Personal Risk For Prime Minister

The missive from the “Former Naval Person” was received with some consternation in Washington. Although anxious for another face-to-face meeting, FDR said in a telegram that he would have preferred a delay “until early stages of mobilization complete here and situation in Pacific more clarified.” Nevertheless, he eventually telegraphed Churchill, “Delight to have you here at White House … My one reservation is great person[al] risk to you [from German U- boats in the Atlantic]—believe this should be given most careful consideration, for the Empire needs you at the helm, and we need you there, too.”

It would be their second meeting. The two leaders had conferred for the first time in August 1941, aboard the battleship HMS Prince of Wales and the cruiser USS Augusta at Placentia Bay off Newfoundland, and had signed the Atlantic Charter, an eight-point declaration of common principles for world peace that would follow “the final destruction of Nazi tyranny.”

Bound for the United States, Churchill and 80 military and political advisers sailed on December 13 from Greenock on Scotland’s River Clyde aboard the Royal Navy’s newest battleship, the powerful HMS Duke of York. The prime minister’s entourage included Lord Beaverbrook, the Canadian-born minister of supply; Admiral Dudley Pound, the first sea lord; Air Marshal Charles Portal, chief of the air staff; and Field Marshal John Dill, who had been replaced as chief of the imperial general staff by General Sir Alan Brooke and would become head of the British military mission in Washington. Also aboard were Roosevelt’s Lend-Lease expediter, Averill Harriman, and Churchill’s personal physician, Sir Charles Wilson (later Lord Moran).

A Rough Crossing For Churchill And Company

The eight-day voyage through stormy seas under gloomy skies set a record for discomfort. The crossing was so rough that the main deck was off limits for the first three days as the battleship sailed southwestward from Ireland, athwart the main path of outgoing and incoming German U-boats. As the Duke of York steamed within 400 miles of the German air base at Brest, France, Churchill became morose, realizing that this was about the same distance that the HMS Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser HMS Repulse had been from the base of the Japanese torpedo bombers that had sunk them off Malaya just a few days earlier.

Most of the Duke of York’s passengers suffered greatly from seasickness, cooped up below decks, but Churchill remained well and worked incessantly. He rankled his dining room companions by telling humorous stories about seasickness. To his beloved wife, Clementine, he wrote, “Being in a ship in such weather as this is like being in prison, with the extra chance of being drowned.”

Films Break Monotony

The British leader spent the greater part of his days working in bed and consoling himself by watching films: Blood and Sand, a bullfight drama starring Tyrone Power and Linda Darnell, and That Hamilton Woman, with Laurence Olivier as Lord Horatio Nelson, which was Churchill’s all-time favorite and moved him to tears.

As the battleship zigzagged across the heaving Atlantic and approached the American east coast, Churchill grew increasingly eager to renew his acquaintance with the American president. After more than two years of solitary struggle by his country (the Battle of Britain; setbacks in France, the Mediterranean, the Far East, and at sea), Churchill was heartened that America was now fully committed and that ultimate victory was assured. On the night of December 7, he had gone to bed and “slept the sleep of the saved and thankful.”

No Patience For River Cruise

The Duke of York eased into harbor at Hampton Roads, Va., on December 22. “It had been intended,” Churchill reported later, “that we should steam up the Potomac and motor to the White House, but we were impatient after nearly 10 days at sea to end our journey.” So the prime minister and his group boarded a plane for the 45-minute flight to Washington National Airport where Roosevelt was waiting, propped up against his car.

The prime minister clasped FDR’s “strong hand with comfort and pleasure,” while the president smiled broadly down upon him (he was a full head shorter than Roosevelt). Fifteen minutes later, the two were at the White House, where a crowd of reporters and photographers waited at the porticoed entrance facing the south grounds, the darkened mall, and the Washington Monument.

In accordance with custom, no pictures were taken during Roosevelt’s long, awkward walk to the mansion doorway on the arm of his naval aide, Captain John Beardall, but then came an explosion of flashbulbs. Clad in a knee-length, double-breasted naval jacket and a cape bearing the insignia of the Elder Brothers of Trinity House (a lighthouse and lifesaving organization), Churchill appeared grim and tired. FDR was buoyant.

Calling White House “Home”

The prime minister showed relief when the brief press encounter ended and he was able to turn away, clamp a big Havana cigar between his teeth, and enter the White House. This, he said later, “was to be in every sense our home for the next three weeks. Here we were welcomed by Mrs. [Eleanor] Roosevelt, who thought of everything that could make our stay agreeable.”

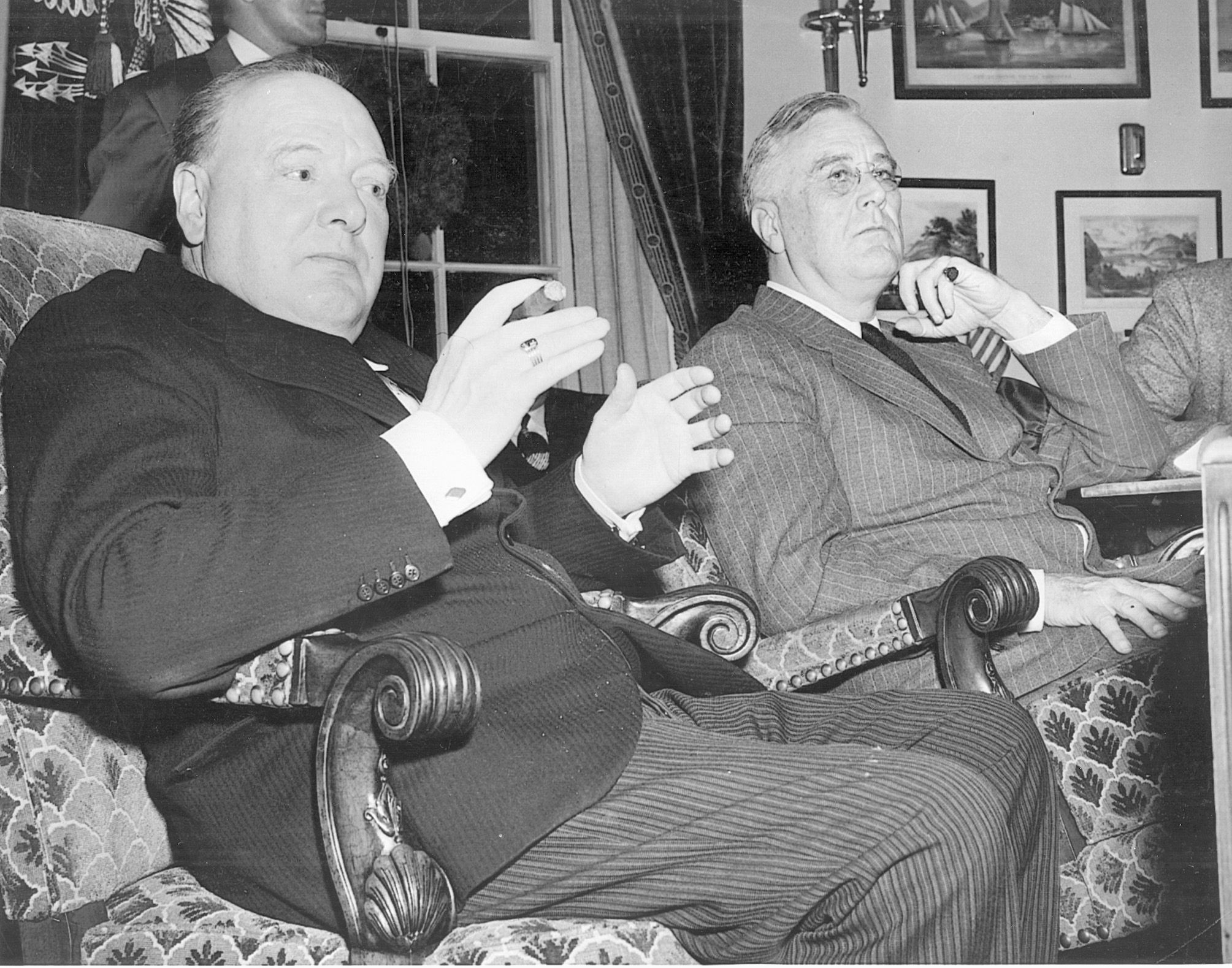

Code-named “Arcadia,” the talks got under way on the first night. The British leader proposed an Anglo-American invasion of French North Africa (Operation Torch) in 1942, and FDR agreed. It was also agreed that the U.S. Army Air Forces should join Royal Air Force Bomber Command in its offensive against Nazi-occupied Europe, and that American troops be deployed shortly to Northern Ireland, relieving British units for other duties, as had been done that summer in Iceland.

The two leaders worked together with harmony and purpose. “We saw each other for several hours every day, and lunched always together, with Harry Hopkins as a third,” Churchill reported. “We talked of nothing but business, and reached a great measure of agreement on many points, both large and small. Dinner was a more social occasion, but equally intimate and friendly.”

An Enduring Friendship Is Forged

The president mixed the cocktails, and Churchill pushed him in his wheelchair from the drawing room to the elevator as a mark of respect, and thinking also of Sir Walter Raleigh spreading his cloak before Queen Elizabeth. The prime minister said he “formed a very strong affection, which grew with our years of comradeship, for this formidable politician who had imposed his will for nearly 10 years on the American scene, and whose heart seemed to respond to many of the impulses that stirred my own.”

The British leader was impressed with all he saw and heard in Washington. He wrote his wife, “All is very good indeed…. The Americans are magnificent in their breadth of view.”

Churchill’s bedroom was directly across the wide hall from that of Hopkins, and he conferred with the frail but tireless adviser as frequently as he did with FDR alone. The wide hallway itself, usually one of the quietest areas in the White House, became for three weeks the nerve center of the British Empire as officers, diplomats, and secretaries scurried back and forth, typewriters clicked, and telephones shrilled.

Next door to Hopkins’ bedroom in the Monroe Room, where Eleanor Roosevelt usually conducted her press conferences, Churchill set up his traveling map room, his “war room.”

Accommodating Churchill’s Habits And Schedule

The British leader said that the president “liked to come and study attentively the large maps of all the theaters of war which soon covered the walls, and on which the movement of fleets and armies was so accurately and swiftly recorded. It was not long before he established a map room of his own of the highest efficiency.” FDR’s war room was established in a former women’s cloakroom in the basement, opposite the elevator and accessible to the handicapped American leader.

Because Churchill made little effort to adjust his long-established daily routine to that of the White House, the mansion’s routine was adjusted to his. The prime minister’s unique work and sleep habits, the unpredictability of his wishes, and his alcohol consumption—a tumbler of sherry before breakfast, two scotch and sodas before lunch, and champagne and brandy in the evening—amazed and regularly disconcerted the White House staff. His bedtime was late. In the White House, as at 10 Downing Street and Chequers, he napped for an hour or two every afternoon and then stayed up until around 3 am. He transacted much of his daily business after dinner.

Churchill and Roosevelt visited each other’s bedrooms during the Arcadia Conference, which lasted from December 22, 1941, to January 7, 1942, as they agreed upon the defeat of Germany as their primary objective. “The days passed, counted in hours,” observed the prime minister.

Tight Security Along White House Perimeter

There were light-hearted moments. One morning, Roosevelt sought out Churchill and found him emerging from the bath. Freshly scrubbed, pink, and naked, the British leader said, “The prime minister of Great Britain has nothing to conceal from the president of the United States.”

Security was tight in the nation’s capital that Christmas season. Sentry boxes had been set up at driveway entrances and at intervals along the White House fence. Soldiers with fixed bayonets patrolled in front of the mansion, and police and soldiers inspected cars on nearby streets. The White House guard had been doubled, and police walked the hallways day and night.

Dim lighting was installed on the White House grounds, and blackout curtains were drawn tight at each window every evening.

A Brief Respite For Christmas Celebration

After two days, FDR and Churchill interrupted their talks for Christmas observances. Christmas Eve was cold and gloomy as security was eased to allow a few hundred invited spectators to gather around the national Christmas tree, set up for security reasons on the White House south lawn instead of in nearby Lafayette Park. Fifteen thousand other people stood outside a steel fence as the president and prime minister stood side by side on the south portico to acknowledge cheers with broad smiles and waved hands.

The Marine Band played “Joy to the World,” and the president pressed a button to turn the dark tree into a blaze of colored lights. He spoke briefly of the incongruity and necessity of honoring the Prince of Peace in a world at war, and then introduced “my associate, my old and good friend.”

Churchill Addresses and Reassures Host Nation

In a short address, Churchill said, “I spend this anniversary and festival far from my country, far from my family, yet I cannot truthfully say that I feel far from home. I feel a sense of unity and fraternal association which, added to the kindness of your welcome, convinces me that I have a right to sit at your fireside and share your Christmas joys…. This is a strange Christmas Eve. Almost the whole world is locked in a deadly struggle, and, with the most terrible weapons which science can devise, the nations advance upon each other….

“Therefore, we may cast aside for this night at least the cares and dangers which beset us, and make for the children an evening of happiness in a world of storm…. Let the gifts of Father Christmas delight their play. Let us grownups share to the full in their unstinted pleasures before we turn again to the stern task and the formidable years that lie before us, resolved that, by our sacrifice and daring, these same children shall not be robbed of their inheritance or denied their right to live in a free and decent world.

“And so, in God’s mercy, a happy Christmas to you all.”

Peace Found In Hymns And Worship

The tree-lighting ceremony was followed by a small social gathering in the White House Red Room attended by the two leaders, the first lady, Beaverbrook, Hopkins, Sir Charles Wilson, and Crown Prince Olav of Norway and his wife, Crown Princess Martha, who had been invited for Christmas by Roosevelt. FDR greatly admired the tall, willowy, and vivacious princess.

On Christmas morning, Roosevelt and Churchill, both Anglicans, attended an interfaith service at the Foundry Methodist Church in Washington. They sang well-known hymns and also one that Churchill had not heard before, the American “O Little Town of Bethlehem.” Its central stanza held special meaning for the times: “Yet in thy dark streets shineth the everlasting light; the hopes and fears of all the years are met in thee tonight.”

Roosevelt had said artfully, “It is good for Winston to sing hymns with the Methodies,” while Churchill reported, “I am glad I went. I found peace in the simple service … It’s the first time my mind has been at rest for a long time.”

Business And a Christmas Feast

The two leaders conferred with their military advisers on Christmas Day, and the prime minister dictated “impromptu remarks” for delivery the following day to a joint session of Congress. At 4:30 pm, the president’s guests opened their presents and he started carving a large turkey for 61 people. After dinner, Churchill uncharacteristically went to bed early, and FDR shouted “Good night!” to his guests and was wheeled away.

On the morning of December 26 (Boxing Day holiday in Churchill’s homeland), the prime minister was driven through large crowds to the Capitol. The occasion—his first address to a foreign legislative body—was historic. As Sir Charles Wilson said, “The two democracies were to be joined together, and he had been chosen to give out the banns.” Churchill was apprehensive because of the large number of isolationist Anglophobes in the Senate, but was inspired. He felt that he was “being used, however unworthy,” as an instrument of mighty purpose. On alighting from his car at the Capitol, he felt compelled to “walk up to the cheering masses in a strong mood of brotherhood,” but security was tight and this was not allowed.

War Befalls America and Britain Twice In a Generation

In the great semicircular Senate Chamber, the British leader stood behind a battery of microphones and scored one of his oratorical triumphs. He opened on a quiet note, saying that he wished his American-born mother, “whose memory I cherished across the vale of years,” could have been there. To loud applause and laughter, he declared, “I cannot help reflecting that if my father had been American and my mother British, instead of the other way around, I might have got here on my own.”

In a passionate plea for permanent Anglo-American unity, he said, “Twice in a single generation, the catastrophe of world war has fallen upon us; twice in our lifetime has the long arm of fate reached across the ocean to bring the United States into the forefront of the battle. If we had kept together after the last war … this renewal of the curse need never have fallen upon us.”

The loudest response came when Churchill spoke of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. “What sort of people do they think we are?” he asked.

Churchill’s Address Wins Over Congress

Concluding his speech on a hopeful note, the prime minister said, “In the days to come, the British and American peoples will, for their own safety and for the good of all, walk together side by side in majesty, in justice, and in peace.” As soon as he had spoken his last word, every senator and representative rose to his feet, all loudly applauding and many cheering.

Back at the White House, Churchill reported, “The President, who had listened in, told me I had done quite well.”

That night, the prime minister found his room hot and stuffy and had to use “considerable force” to open the window, which was stiff. He became short of breath and felt a dull pain over his heart that went down his left arm. Wilson realized that it was a slight heart attack but withheld the news from both Churchill and the public.

War Plans Drawn Up For “United Nations”

Advised to avoid undue exertion, the prime minister continued talks with Roosevelt and their advisers. It was agreed that the Allied military effort in 1942 would focus on an accelerated air offensive and naval blockade against Germany and on generous assistance to the Soviet Union.

The prime minister paid a three-day visit to Ottawa, addressed the Canadian Parliament, and returned to Washington on New Year’s Eve. At midnight, he toasted the reporters accompanying him: “Here’s to 1942. Here’s to a year of toil—a year of struggle and peril, and a long step forward towards victory.”

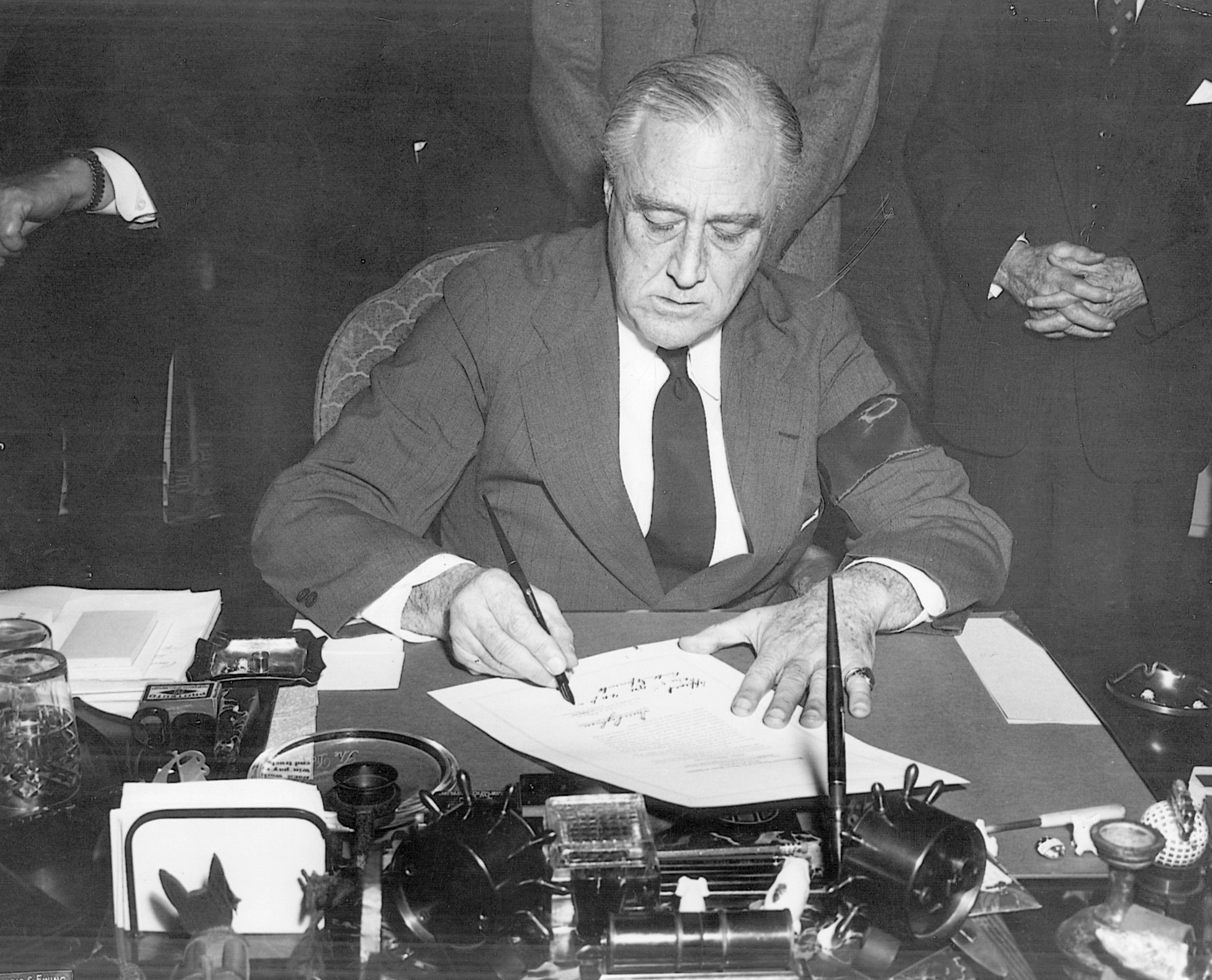

On New Year’s Day, 1942, Churchill and Roosevelt signed a declaration—later adhered to by Russia and the other Allied nations—proclaiming the “United Nations.” The alliance pledged to make war and peace together and that no member should make a separate peace with the enemy. The phrase “United Nations” was coined by FDR.

A Florida Vacation, Then Home To Face Challenges Ahead

The pace and pressure of the Arcadia talks wearied Churchill, and for five days early in January he rested at the Palm Beach, Fla., villa of Lend-Lease administrator Edward Stettinius. It was the prime minister’s first vacation for almost three years.

On January 15, he left Washington for Bermuda, where the Duke of York was waiting to take him home. On the spur of the moment, he decided to save time by flying the Atlantic aboard the Boeing clipper which had brought him to Bermuda. Characteristically, the irrepressible prime minister took the controls during the flight.

He arrived home to face grim tidings. Public opinion was restive about the loss of HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse and over Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s successes in the Western Desert, and Japanese troops were advancing on the British bastion at Singapore.

The road to victory would indeed be long, but the Arcadia Conference had established a blueprint for the ultimate triumph.

I have a question.. i have a photo of FDR and Churchill that was in my grandpa’s photo book from his Stent at Panama Canal (he was an Army corps of engineers)… surrounded by many other photos…. has 31 on the back…know anything?