By A.B. Feuer

The story of the sinking of the USS Indianapolis minutes after midnight on August 30, 1945, by torpedoes fired from the Japanese submarine I-58, remains one of the most publicized tragedies of World War II. And the rescue of its commanding officer, Captain Charles McVay III, only adds to the mystery that has shrouded the incident for more than 50 years.

In an interview with this writer, Captain William Meyer, USN (Retired), relates his untold story of the extraordinary rescue operation: “I was commanding officer of the USS Ringness—a high-speed destroyer transport,” Meyer began.

“On July 29, in company with the USS Register—another destroyer transport, skippered by Lt. Cmdr. John Furman—we departed Leyte Gulf as escorts for two jeep carriers, the Chenango and Gilbert Islands. Our destination was Ulithi in the western Caroline Islands.

“Our flotilla arrived off Ulithi in the early morning of August 1. And, after guiding the carriers safely inside the lagoon, the Ringness and Register hurriedly headed back to Leyte. We did not take time to refuel, however, which I later realized was poor judgment on my part.

“Late the following afternoon, we received a radio message from nearby patrol aircraft to help in the hunt for a possible enemy submarine in our area. The search proved negative, and we resumed our course to Leyte. About 8 pm, I received a short four-word message from cinpac [Commander in Chief Pacific]—‘Survivors in the water!’ The Ringness and Register were ordered to proceed, ‘at best possible speed,’ for a rescue mission 250 miles northeast of our present position. We steamed at 20 knots all night—arriving at the general area about 9 o’clock on the morning of August 3. The Register was directed to cover a search area to the north of the Ringness. Other rescue vessels were to the east and over the horizon.

“At 9:15 am, our lookouts sighted a lone sailor clinging desperately to a small raft. He was nearer the Register and that ship was instructed to pick the man up.

“We continued northeast where search aircraft were soon spotted. According to published books written on the subject, the Ringness made radar contact on a 40mm ammunition box. None of our officers or men, however, can recall this occurrence. It was the circling planes that directed our course.

The Search for Survivors

“As we approached the scene, all hands not required to man the engine, fireroom, the CIC, or the radio were called on deck, and stationed as high as possible to visually look for survivors. I decided not to use our four LCVP landing craft to pick people out of the water. Boat crews had limited horizontal sight, compared to lookouts on the ship. And, any men picked up by the boats would still have to be transferred to the Ringness.

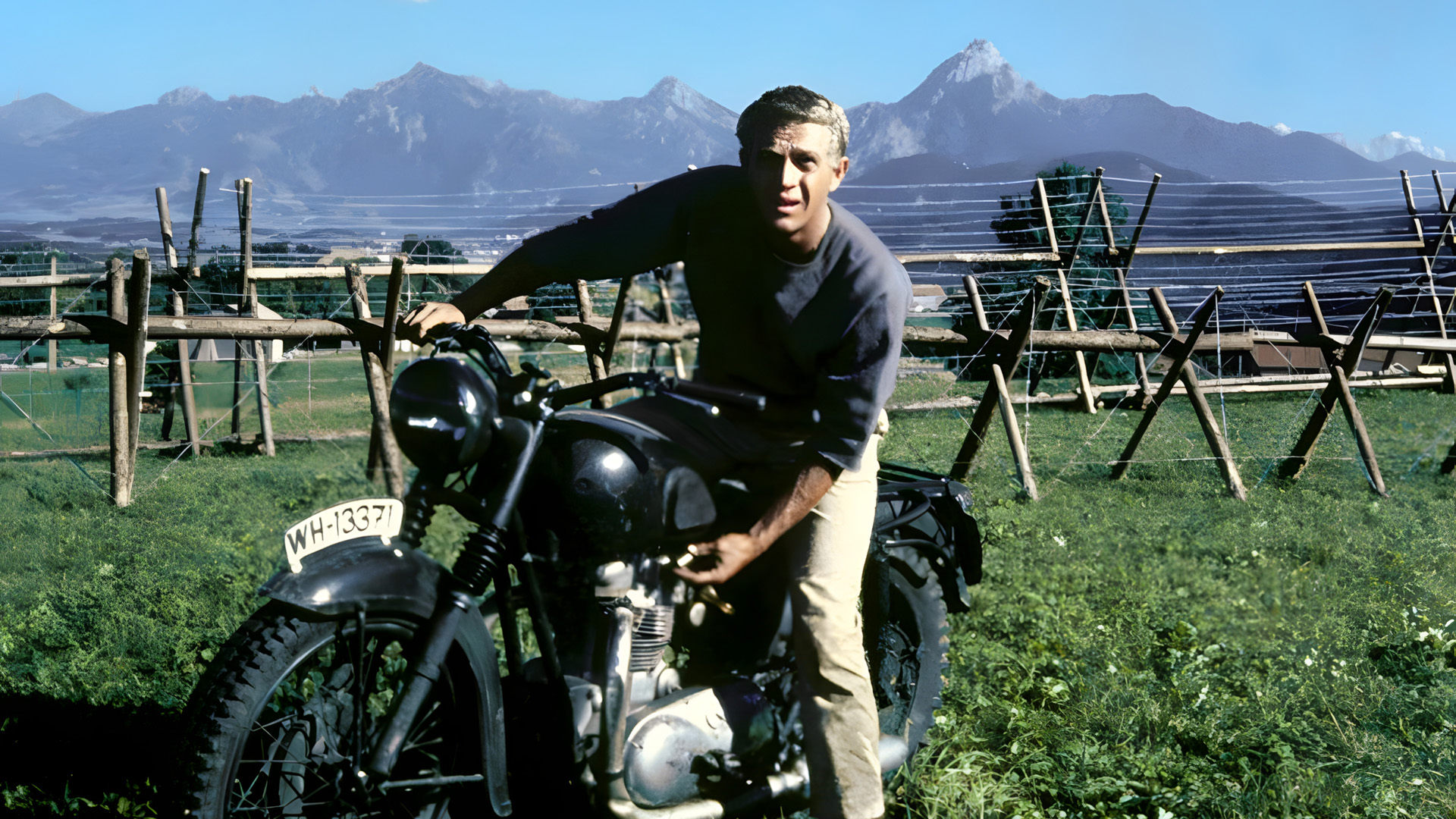

“About 10 am, we came upon our first group of survivors—eight or nine men aboard three rafts that were lashed together. One of the men, an officer in khakis, was standing up and frantically waving his arms, as if we did not see the rafts and were going to run them down. The Ringness was carefully maneuvered alongside the rafts, and the survivors clambered up cargo nets with a minimum of assistance from our crew.

“The rescued officer proved to be Capt. Charles B. McVay III, commanding officer of the Indianapolis. Concerning the rescue, one author stated: ‘McVay stumbled to the bridge and stammered out his story to Lt. Cmdr. William C. Meyer, skipper of the Ringness.…’ This statement is just not true. When Captain McVay came aboard, he received immediate medical attention, and was bedded down in the CO’s cabin. He was too honorable a naval officer to interrupt a ship’s company involved in rescuing his men from the sea. My first personal contact with the captain was in my cabin about 1 o’clock. This was after I determined our sector had been fully covered, and I had checked with our ship’s doctor as to whether it would be all right to talk to Captain McVay.

”Our Presence Did Not Deter the Sharks One Bit”

“But to get back to the rescue operation. As the survivors climbed aboard the Ringness, they were assisted by members of my crew to remove oil-soaked life jackets and clothing. They were then escorted to sick bay where the medical team took over—cleaning the sticky oil from their bodies, and giving each man a physical examination. Clean dungarees—and a uniform for Captain McVay—were donated to the Indianapolis survivors by the men of the Ringness.

“The most memorable incident of the day was rescuing two sailors who were sitting on top of a rolled-up floater-net—a webbing of manila rope interlaced with cork balls to keep it afloat. The web mats—tied with light lashings—are located aboard ship, and float away if the vessel sinks. These men had left their net rolled up, and sat on the strange-looking barrel for about four days and nights without falling off—an incredible feat.

“Upon pulling alongside the floater-net, I was shocked to notice several large, hungry sharks circling the sailors—waiting for a man to fall off. Our presence did not deter the sharks one bit. Even after the sailors were saved, the sharks continued their vigil around the empty net.

“By 1 o’clock, we had rescued most of the Indianapolis survivors in our area. Only then did I feel confident that I could leave the bridge and check on Captain McVay. When I entered the cabin, the captain was resting comfortably. He did not get up, but continued to lie in the bunk. I sat in a nearby chair. McVay assured me that he was willing to talk about the loss of his ship, and wanted to contribute to a message I was preparing to send to cinpac regarding the results of our rescue efforts.

A Traumatized Captain Tells His Tale

“I had made a rough draft of the dispatch, and read it to Captain McVay—asking for his comments. McVay related the basic information as to conditions on the evening of July 29, and what he could remember concerning the sinking of the Indianapolis. At first, the captain was very emphatic that I should not include the fact that his cruiser was not zigzagging. It was evident to me, however, that this was bothering him. Understandably, he was still traumatized. But, I felt strongly that the truth had to be revealed since it would come out in any board of inquiry that would certainly be conducted. After much discussion, Captain McVay agreed to the final draft of the message:

‘Have 37 [Indianapolis] survivors aboard including Capt. Charles B. McVay III, commanding officer. Captain McVay picked up at Lat. 11-35, Long. 133-21, with nine other rafts within radius of four miles, and states he believes ship hit 0015, sunk 0030, July 30. Position on track exactly as routed by Guam. Speed 17 knots, not zigzagging. Hit forward by what is believed to be two torpedoes, or magnetic mine, followed by magazine explosion.’

“We continued a search of the area, and late that afternoon noticed a plane drop a smoke flare some distance north of our location. The Ringness raced to the scene, and found a raft carrying the last two survivors—Pvt. 1st Class Giles McCoy, of the cruiser’s Marine detachment, and Seaman 1st Class Bob Brundige. McCoy, a typical Marine, refused help in climbing aboard ship. However, once on deck, he fell flat on his face—but was quickly revived in sick bay.

“The author of one book on the sinking of the Indianapolis wrote: ‘The last living man plucked from the Philippine Sea was Captain McVay, who was the last man to enter it.’ This statement is in error. The last living person to be saved would be either Bob Brundige or Giles McCoy—six or seven hours after McVay was rescued.

Remarkable Resiliency

“A short time later, we discontinued our search and—in company with the Register—proceeded to Peleliu Island to transfer the Indianapolis survivors to a shore-based hospital.

“The resilience of the American sailor has never ceased to amaze me. We had picked up Captain McVay and 38 members of his crew. The survivors had spent more than four days in the unfriendly ocean—soaked in oil, without food or drinking water, and threatened by prowling sharks and physical exhaustion. And yet, when we reached Peleliu, many of the men were able to walk under their own power.

“One thing that I have always regretted, however, is not having made a transcript of Captain McVay’s comments prior to leaving the Ringness. As we approached Peleliu, McVay came to the bridge and requested permission to speak to my crew. The request was granted, and his heartfelt remarks of thanks and appreciation—on behalf of his men—showed the top-notch quality of Captain McVay. He was an officer and a gentleman—with deep-seated human qualities of humbleness and compassion—and a strong belief in the existence of a Higher Being.

“Before departing Peleliu, we went alongside a tanker to refuel. It was then that I realized my poor judgment in not refueling at Ulithi. Our engineering officer, Ensign J.P. Strickland, reported that the Ringness only had two hours steaming left in her bunkers. I never made that mistake again, and kept the fuel tanks topped off at every opportunity.

Did Anyone Else Survive?

“Both the Ringness and Register hurriedly returned to the search area, and joined an armada of vessels looking for additional survivors of the Indianapolis. But results were negative, and at 6 am, on August 5, the search was called off.

“I might add one interesting observation. Throughout the entire rescue operation—while covering our assigned area—we did not notice a single body floating in the water. I have read, and heard, many accounts of ships picking up drowned sailors—but not by the Ringness.

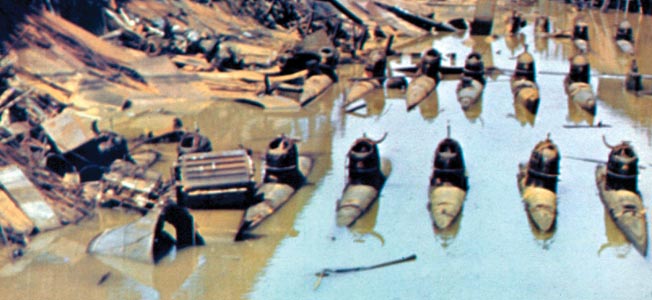

“Unfortunately, my memory fails me in trying to remember how we destroyed the life rafts and floater-nets. But once survivors were brought aboard, my attention was focused on the next group of men to be rescued. I do not remember seeing anything floating after each pick-up had been completed. It is possible, that as soon as a raft or floater-net was empty, some of my men disposed of it. We had an alert and very innovative crew.

Unanswered Questions

“There are many circumstances concerning the sinking of the Indianapolis that still bother me after more than 50 years. Although I do not know all the facts, I have always wondered why the cruiser was permitted to transit without an escort across a tract of ocean where Japanese submarines were still active. There had to be at least one ship available to accompany the Indianapolis between Guam and Leyte. The destroyer-escort Underhill was torpedoed only two weeks earlier [July 24] along the same route.

“True, the war was winding down, but the atomic bomb had only been delivered by the Indianapolis—not dropped! The U.S. Navy was at the peak of its availability of ships—especially antisubmarine vessels. Although we were training and planning for the invasion of Japan in November, there was still no excuse for sending the cruiser out unescorted.

“And finally—since I’m spouting off—the general court-martial trial of Captain McVay was a terrible travesty of justice.

A Survivor’s Recollections

Over the years, my wife and I have attended a number of Indianapolis Survivors Association reunions. We also were present at the dedication of a beautiful memorial in the city of Indianapolis, and feel very close to the survivors who are still living.

“Some years back, John Jarman, a member of our crew, related an interesting story to me regarding the rescue of Captain McVay. Jarman had assisted the captain aboard, helped him out of his oil-soaked life jacket, and took him to sick bay. John also noticed a flare-gun attached to the captain’s life preserver. Jarman learned that McVay had used the gun to light a last cigarette on the last night that he and his men were in the water. They were virtually ready to give up any hope of being found.

“After Captain McVay was safely in sick bay, John went back to the pile of oily jackets, removed the flare-gun, and stowed it in his locker. Fifty years later, in 1995, Jarman delivered the gun to me. The following year—at the general meeting of the Indianapolis Survivors Association Reunion in Indianapolis—I gave this memento to the association as a small part of the USS Indianapolis that survived the sinking 51 years earlier.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments