By James M. Powles

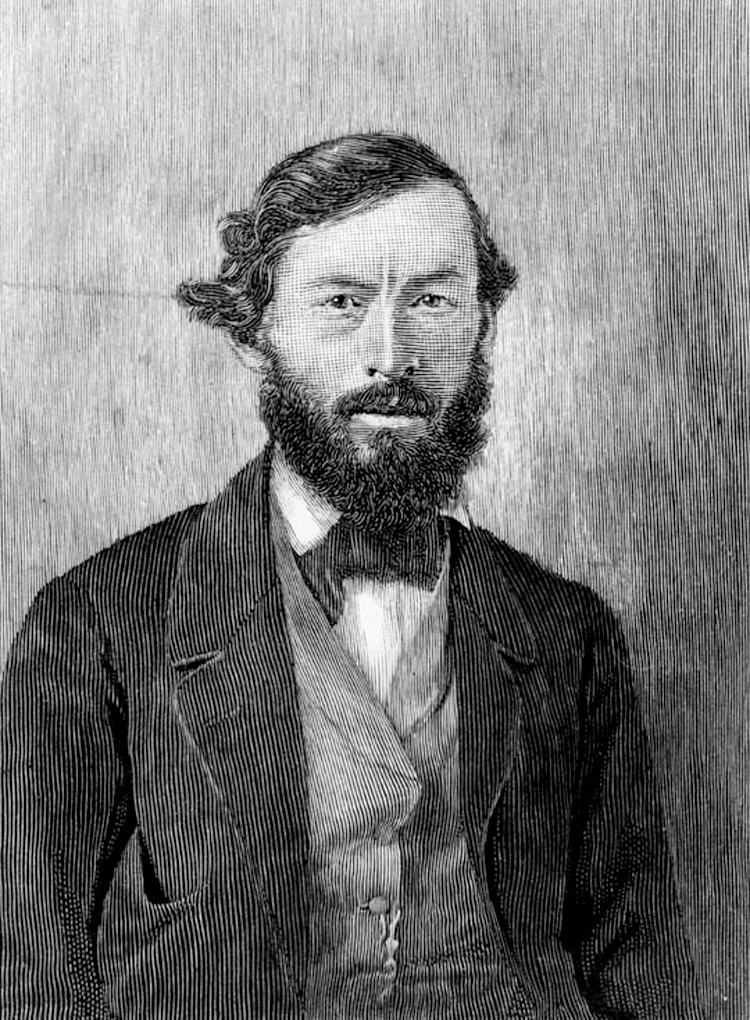

The epic battle between the Virginia (Merrimack) and Monitor might never have taken place because, as strange as it may seem, the Confederates did not have enough experienced men to man their ship. The problem was solved by John Taylor Wood, a 31-year-old Confederate naval officer of unusual skill and resourcefulness. Lieutenant Wood joined the Virginia in January 1862 and was given the responsibility of recruiting a crew for the ironclad, which was not as easy as it seemed. The Confederate Navy had plenty of former U.S. Navy officers, but lacked trained sailors. Before the war, the majority of naval officers had come from the South, while the enlisted men usually were from the North.

Because there were not enough seamen in Norfolk to man the Virginia, Wood traveled to the Army camps at Yorktown, Richmond, and Petersburg in search of volunteers who had sea or gunnery experience. These forces were themselves short on men, so it was not easy to persuade their commanders to release any of their soldiers. But through perseverance, Wood was able to get quite a few men who had the necessary experience. In a surprisingly short time, Wood managed to gather a crew of 300 men made up of seamen, gunners, and marines and filled out with Army volunteers.

Virginia Crew “as Gallant and Trusty a Body of Men as Anyone Could Wish To Command”

Wood assembled the men at the Norfolk Navy Yard and drilled them as much as he could in the limited time he had. By March 8, when the Virginia left the Navy Yard for her initial trial run and first battle, her crew was skilled. Wood described them “as gallant and trusty a body of men as anyone could wish to command.”

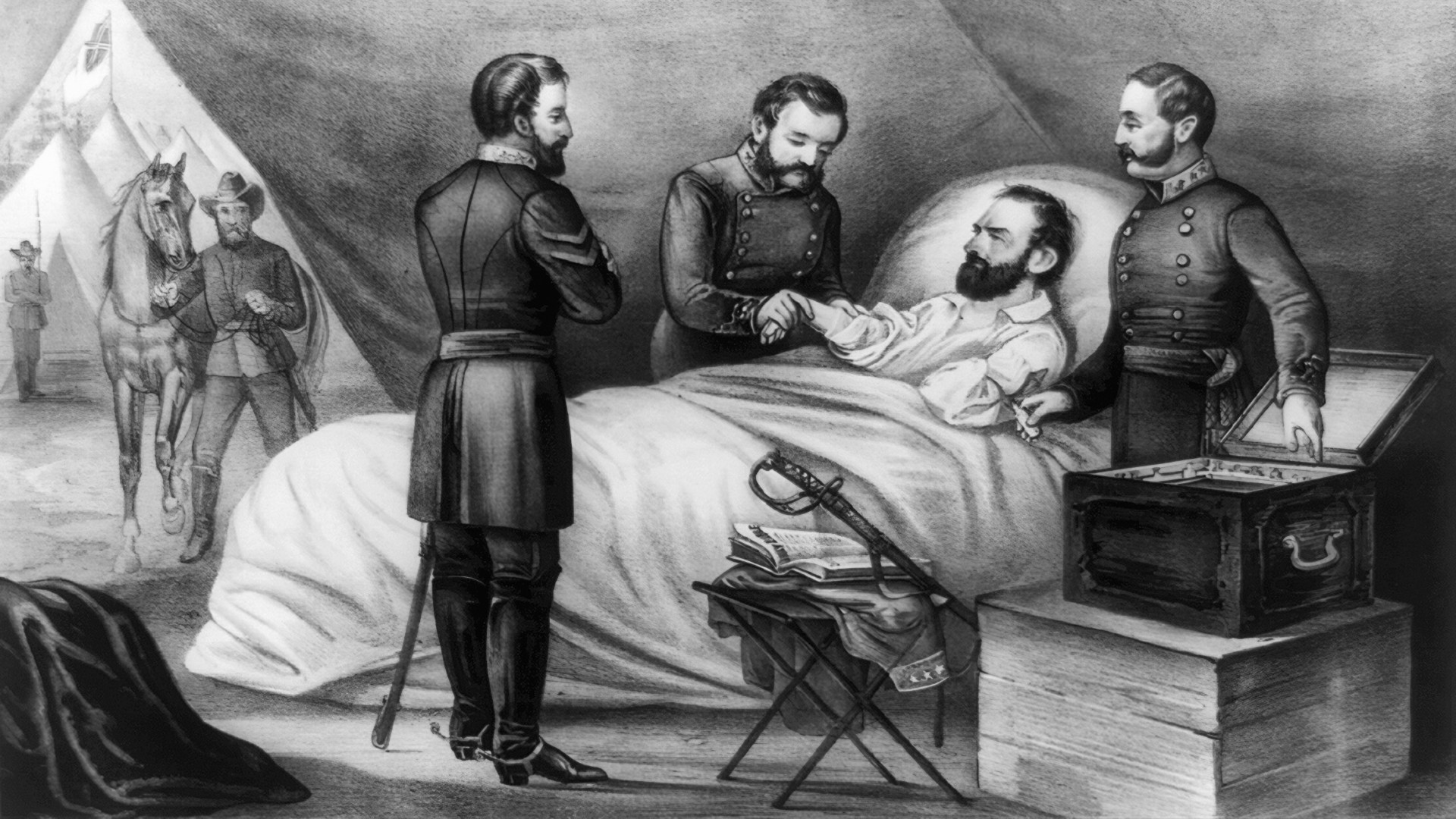

During the battle that day and the next, Wood was in charge of the aft pivot gun, a 7-inch Brooke rifle. It was this gun, aimed by Wood, that fired the shot that struck the Monitor’s pilothouse and wounded her captain, Lieutenant John L. Worden. Wood also came up with the idea to board the Monitor. He organized a boarding party and equipped the men not only with small arms, but also with sledgehammers and wedges to jam the Monitor’s turret, oakum-ball grenades to drop inside the ironclad, and canvas to cover the vision ports and ventilators. Unfortunately for Wood, just as the two ironclads closed, the Monitor veered away and headed into shallow water where the Virginia could not go.

Captain Franklin Buchanan, commander of the Virginia, said of Wood’s performance: “Lieut. Wood handled his pivot gun admirably, and the executive officer [Lt. Catesby Jones] testifies to his valuable suggestions during the action. His zeal and industry in drilling the crew contributed materially to our success.”

After the battle, Captain Buchanan sent Wood to President Jefferson Davis in Richmond with news of the battle and the bloodied flag of the surrendered USS Congress. Wood soon returned to the Virginia, and when the Confederates evacuated Norfolk he worked tirelessly to lighten the ironclad so she could be taken up the James River to safety. When this failed, he helped in her destruction on May 11.

Wood was born on August 13, 1830, at Fort Snelling, Iowa Territory (St. Paul, Minn.). His father was General Robert Crooke Wood, a U.S. Army surgeon and assistant Surgeon General from 1862 to 1865. His mother was Anne Mackall (Taylor), daughter of Zachary Taylor and sister of Jefferson Davis’s first wife.

Instead of following his father into the Army, Wood entered the Navy in April 1847 as a midshipman. During the Mexican War, he served on the frigate Brandywine off Brazil and the ship-of-the-line Ohio in the Pacific Ocean. After the war he continued his career in the Navy and in June 1853 he graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy, second in his class. In 1855, he was promoted to lieutenant and the following year married Lola Mackubin of Annapolis; they eventually had 11 children.

John Taylor Wood Supported the Confederate Cause

When the Civil War began, Wood was an instructor of tactics and gunnery at the Naval Academy. Because his sympathies lay with the South, he resigned his commission in April 1861 and returned to his farm in Maryland. As the war proceeded through the summer, Wood tried to stay neutral but gradually became a supporter of the Confederate cause and joined the Virginia State Navy as a lieutenant. Consequently, Wood and his father, who was then stationed in Washington, stopped speaking to one another. Wood’s younger brother, Robert Crooke Wood, Jr., a graduate of West Point and a U.S. Army officer, also left the Union for the South and served as a Confederate cavalry officer. Before joining the Virginia, John Taylor Wood was stationed along the Potomac at the batteries at Evansport and Aquia Creek.

In December Wood was appointed a lieutenant in the Confederate Navy by Davis, retroactive to October 4. Although Davis was his uncle, Wood was more than a mere political appointee. He was intelligent, a good planner, an exceptional leader, and was well versed in naval tactics. Despite being a strict disciplinarian, he was respected by those he commanded for his courage and skill in battle. He had much influence with the Confederate government and Navy Department, more than his rank or position would indicate, but this influence was due more to his ability and knowledge than to who his uncle was.

Wood and Crew Head to Richmond, Join Forces

With the destruction of the Virginia, Wood and the rest of the ironclad’s crew went to Richmond, where they found the city preparing for an attack by the approaching Union forces. Wood and the Virginia’s men were immediately sent seven miles below the city to a 200-foot-high prominence overlooking the James River called Drewry’s Bluff. Here they joined other Confederate forces in building earthworks and batteries and sinking obstructions in the river—an attack upon Richmond by Union gunboats coming up the James River was expected at any time.

The Confederates did not have long to wait. On May 15, just two days after Wood arrived, a flotilla of Union gunboats appeared. The flotilla comprised the new ironclad Galena and four other gunboats, including the Monitor. When the Union ships came within 600 yards of the Confederate positions, they opened fire and a hotly contested artillery duel ensued.

The battle raged for almost four hours until the Union gunboats, finding that they could not overcome the high Confederate works, retreated down the river. During the battle, Wood was in command of a company of sharpshooters entrenched along the riverbank. Despite being under constant rifle and cannon fire, Wood’s men poured out a steady and accurate fire that helped keep the Union gunboats at bay. Wood was later commended for his actions and those of his men. Wood said of the battle, “The fight at Drewry’s Bluff … was the salvation of Richmond.” The Confederate victory, indeed, had prevented the Union from reaching Richmond that day.

Embarking on Nighttime Vessel Raids

Several months later Wood embarked on the first of his feared and famous nighttime raids on the Chesapeake Bay. On the night of October 7, 1862, Wood and 13 men boarded and captured the Union transport schooner Francis Elmore, which was anchored off Lower Cedar Point in the Potomac. After taking the captain and crew prisoner, he burned the vessel.

At the end of the month Wood made another raid. With volunteers from the Confederate gunboat Patrick Henry in three small boats, Wood came upon the ship Alleganian anchored near the mouth of the Rappahannock River. He and his men boarded the ship—there was a storm raging at the time—and without a fight took her surprised crew prisoner. After seizing the ship’s stores, Wood put some of the prisoners in his boats and set the ship afire. Although several Union gunboats were in the area, Wood made it to shore safely—the Alleganian and her cargo were a total loss.

In early 1863, Wood was appointed naval aide-de-camp to President Davis and made a colonel of cavalry (near the end of 1861 the Confederate Congress allowed Davis to give naval officers Army rank). For the rest of the war Wood held commissions in both the Confederate Army and Navy, changing his rank between the two services as his duties required. As Davis’s aide, Wood inspected the South’s coastal and river defenses and ship construction and naval facilities, and acted as liaison officer between the Army and Navy. During this time Wood made some of his most important contributions to the Confederacy.

“The Absolute Necessity of the Place … Is Heavy Guns”

While on an inspection tour of Wilmington in February 1863, Wood reported to President Davis, “The absolute necessity of the place, if it is to be held against a naval attack, is heavy guns. With over 100 guns bearing upon the water, there is but one 10-inch, no 9-inch, and but few 8-inch; 24s and 32s form the armament of most of the batteries.” This report led to Wilmington receiving heavier guns. As a result of this and other recommendations he made for improving the defenses of Wilmington, and later Charleston, these important ports were able to remain open longer to blockade runners. Wood was also concerned with making improvements in the Confederate Navy, vigorously pushing to have more active, younger men placed in positions of authority.

Wood went on another one of his nighttime raids on August 19, 1863. He departed Richmond with 60 men and headed for the Chesapeake. He meant to attack the two ships of the Union’s Chesapeake flotilla that were patrolling the area off the Rappahannock River, the armed steamers Satellite and Reliance, each mounting two guns and manned by a crew of 40.

Three nights later, Wood and his party set off from the Virginia shore in four small boats toward the gunboats, which had anchored for the night off Stringray Point. The Confederates made it to the gunboats undetected and quickly boarded both vessels. After fierce hand-to-hand fighting, they captured the two gunboats and took their crews prisoner. Wood immediately took the gunboats up the Rappahannock to Urbanna, where the prisoners were put ashore.

Two nights later Wood took the Satellite out into the bay in search of Union shipping and captured a large schooner carrying coal, which he badly needed, and two smaller schooners. He brought his prizes back to Urbanna the next day. Within another couple of days Wood took the two Union gunboats and the small schooners up river to Port Royal, where he received a hero’s welcome. But with Union forces closing in around Port Royal, Wood stripped the four Union vessels of their guns and all other usable equipment and burned them to prevent their recapture. Wood’s expedition was a great morale booster for the Confederacy and a blow to the Union naval forces on the Chesapeake. For this raid Wood was promoted to Navy commander and went back to his work on Davis’s staff.

Wood’s Flotilla Set To Capture Union Gunboats

In the beginning of 1864, Wood led a flotilla of ship’s boats, in conjunction with a land attack by Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett, on New Bern, NC. Wood’s flotilla was to come down the Neuse River and capture the three Union gunboats that patrolled the area, while Pickett made a three-pronged attack on the Union forces around New Bern.

On the night of February 1, Wood, with some 300 officers, seamen, and marines in 12 boats, approached New Bern. When he arrived, Wood found only one of the Union gunboats, Underwriter, there. Underwriter was a 186-foot sidewheel steamer with a crew of 84, mounting four guns, and was the largest gunboat in the area. She was anchored near the shore, close to Fort Stevenson and a land battery.

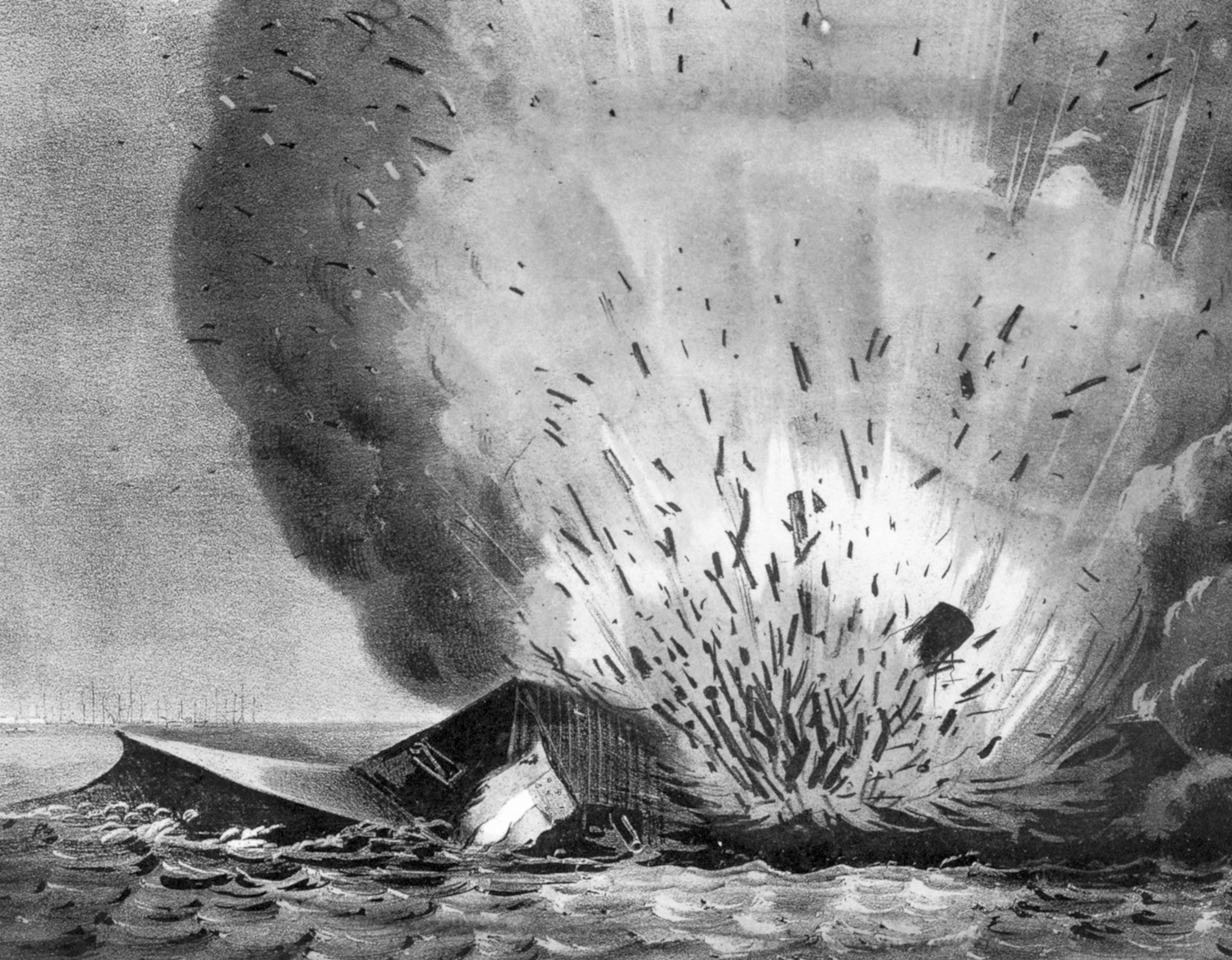

At 2:30 am on the 2nd, the Confederate boats made for Underwriter, but just as they neared the gunboat they were spotted. But, before the Union seamen could mount an effective defense, Wood and his men had reached the gunboat and boarded her. A fierce and bloody fight ensued. After a stout resistance, the gunboat’s crew was overpowered and surrendered.

Wood wanted to flee with his prize but found that the gunboat’s boilers were cold. Moreover, Union troops on the shore realized that Underwriter had been captured and opened fire. According to Wood, “Her position [was] within musket-range of several strong works, one of which was raking the vessel during the time we had possession.” Under fire and with no hope of getting steam up quickly, Wood reluctantly torched the gunboat and escaped back up the Neuse with his men and prisoners. Along with Underwriter, the Union lost some 30 killed and wounded with 26 taken prisoner, while Wood had five killed, 15 wounded, and four missing.

“Joint Resolution of Thanks to Commander Wood and His Men, for Their Daring and Brilliant Conduct”

Although the Confederates failed to take New Bern, Wood’s part was a success. He was praised throughout the Confederacy and offered a promotion, which he modestly declined. In recognition of his recent gallantry, the Confederate Congress, on February 15, 1864, passed a “joint resolution of thanks to Commander John Taylor Wood and the officers and men under his command, for their daring and brilliant conduct.” After New Bern, Wood returned to Richmond and helped to coordinate the capture of Plymouth, NC, in April.

At the beginning of July, Wood presented to General Robert E. Lee a plan to free the nearly 20,000 Confederate prisoners of war being held at the Union prison at Point Lookout, Md., on the Chesapeake Bay. Lee liked the plan and agreed to send a detachment of cavalry to make a simultaneous attack from land while Wood made an amphibious assault.

With a force of 200 men, Wood left Richmond for Wilmington, NC. They joined with a detachment from the Wilmington naval squadron and boarded two blockade-runners, the Florie and the Let Her Be. On the night of July 10, the two blockade-runners set out for the Chesapeake, but before they could reach the open sea, they received a signal from Fort Fisher to return.

Wood went ashore where he was given a message from Richmond informing him that the enemy might be aware of his intentions. Wood dismissed the message, but while preparing to leave the next night he received orders from Davis canceling the expedition. Wood was disappointed, but he was fortunate, because his plans really had been leaked to the Union.

Steering up the Coast To Destroy More Vessels

At the end of July, Wood was given command of the Confederate raider Tallahassee, formerly the fast blockade-runner Atlanta (or Atalanta). On the night of August 6, after being fired on by several blockaders and outracing several others, the Tallahassee successfully ran out of Wilmington. Once at sea, Wood steered up the coast to the lucrative hunting grounds off New York and New England.

On August 11 Wood captured his first prize off New Jersey, and before the day was over had seized six more. The next day he was off the entrance to New York Harbor where he bagged several more vessels. While there he concocted a scheme to “go up the East River, setting fire to the shipping on both sides, and when abreast of the [Brooklyn] Navy Yard to open fire.” But he was unable to execute this daring plan because he could not get any of the pilots he had captured to guide him through the tricky New York waters.

Leaving New York, Wood steamed along Long Island and up the coast of New England, taking more vessels along the way. Reaching Maine, he was low on fuel and put into Halifax, Nova Scotia, for coal and to make repairs. His stay was brief. At 1:00 am on the 20th, the Tallahassee sneaked out of Halifax, missing by only a few hours the USS Pontoosuc, one of several Union warships pursuing her. On the way home, Wood captured one more vessel. On August 26 the Tallahassee, after a running gun battle with three blockaders, anchored under the guns of Fort Fisher.

In only 19 days at sea, Wood captured or destroyed 33 vessels. In the South the Tallahassee’s voyage was hailed as a great victory and was a badly needed morale booster. For the North, “she certainly kicked up a fuss” by forcing more Union vessels from the seas, and caused the Federal government to tighten the blockade, especially at Wilmington. Wood was promoted to naval captain in February of 1865.

After the Tallahassee cruise, Wood returned to his duties as Davis’s aide, spending most of his time in coordinating the Army and Navy in their defense of Richmond. He was offered the command of the James River Squadron but declined, preferring to stay as Davis’s aide.

A Loyal Confederate until the End

Wood was with Davis in church on Sunday, April 2, when the president received the urgent message from General Lee that Union forces had broken his lines and Richmond had to be evacuated. That night Wood accompanied Davis and the Confederate government as they went south through the Carolinas to Georgia. Wood was captured with Davis on May 10, 1865, at Irwinsville, Ga., but he escaped shortly after by bribing his guard and hiding in a swamp until everybody had left.

Several days later, near Madison, Fla., Wood met General John C. Breckinridge and other Confederate refugees. He and Breckinridge formed a small party and traveled on horseback to Fort Butler on the St. John’s River, where they obtained a small open boat. Under Wood’s guidance the party navigated the St. John’s to the Indian River and thence to the Atlantic just south of Fort Pierce on June 4.

Although Wood felt that the boat was too small, they tried to row east, across to the Bahamas, but were unable because of strong headwinds. Wood then decided that they should head south and try for Cuba. As they rowed down the coast on June 6, they were stopped by a Union gunboat, but Wood was able to bluff their way through. Farther along, Wood made his last capture at sea when he came upon a small sloop carrying Union deserters. Wood was able to “convince” the deserters to trade their sloop for his boat. The sloop was not much bigger, but it had a higher freeboard, was partially decked, and it had a mast and sail so going to Cuba was now possible.

They made the crossing through a terrible storm, arriving in sorry shape but looking forward to starting new lives. Wood stayed in Cuba less than two weeks. Because President Andrew Johnson’s amnesty proclamation excluded Confederate naval officers above the rank of lieutenant and those educated at the Naval Academy, he could not return to the United States, so he decided to go to Canada. After his wife and children joined him they settled in Halifax, where he was involved in shipping and marine insurance and became a prominent citizen of the city. With the war over, he made up with his father and in later years he returned to the United States but only to make short visits. He died in Halifax on July 19, 1904, a loyal Confederate to the end.

Deo Vendice

It seems that most of your articles favor the Confederacy. I wonder how they lost the war

Yes it was a wonder how they lost the war. They had the better fighters. They just did not have enough food!