By David Alan Johnson

During the summer of 1940, Winston Churchill was fighting a two-front war. The first was against Adolf Hitler and his war machine, particularly his Luftwaffe. The second was against a United States that was determined to remain neutral at all costs: against a defeatist U.S. Ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy; against an isolationist American public; and against a politically pragmatic President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

On July 16, 1940, Adolf Hitler issued “Directive No. 16 on the Preparation of a Landing Operation Against England”: “Since England, despite her militarily hopeless situation, still shows no willingness to come to terms, I have decided to prepare a landing operation against England, and if necessary to carry it out.”

Actually, Hitler did not look forward to an invasion of England, and would have preferred an armistice. But he had absolute confidence in his military forces. In just six weeks, the German Army and Luftwaffe had overrun Belgium and the Low Countries and forced France to surrender—something that the Kaiser’s armies had not been able to accomplish in more than four years. During July, the Wehrmacht began preparations for Operation Sea Lion, the invasion of England’s channel coast. At the same time, Luftwaffe bomber and fighter units began moving to bases in northern France, a few minutes’ flying time from southern England.

Britain had made it very clear that it had no intention of asking for an armistice. Three days after he had issued his Directive No. 16, Hitler delivered a peace proposal to Britain in a speech from the Reichstag, which he called “a last appeal to reason.” “I really do not see why this war should continue,” he told his audience, and called Prime Minister Winston Churchill a “criminal warmonger” for refusing to come to terms with him. But British correspondent Sefton Delmer broadcast a reply to Hitler’s “last appeal” the same day. He told Hitler that “we hurl it right back at you, right back in your evil-smelling teeth.” It was not an official response, but it said exactly what Winston Churchill had in mind.

Churchill realized that the impending battle would be critical. He also knew that Britain was in no condition to fight a protracted war against Germany. The French campaign had been a disaster for British forces. Although over 300,000 British and French troops had been evacuated from the beaches at Dunkirk, most arrived in Britain without any of their equipment. Only one fully equipped division could be activated against a German invasion, and that was a Canadian division. RAF Fighter Command also had been heavily depleted, having lost nearly half of its strength over France—more than one hundred fighters had been shot down over Dunkirk alone.

Churchill could see that Britain could not survive alone and desperately needed allies. Specifically, Britain needed the backing and support of the United States—American money and materiel. But he was also well aware that Americans were determined to remain neutral. A Gallup poll taken in May 1940 indicated that 64 percent of Americans opposed sending any help to Britain and wanted no part of the war. Charles Lindbergh, the aviation hero of the 1920s and a blunt isolationist, spoke for the majority of his countrymen: “We must not be misguided that our frontiers are in Europe. What more could we ask for than the Atlantic Ocean on the east, and the Pacific on the west?”

The American ambassador to Great Britain, Joseph P. Kennedy, was just as outspoken as Lindbergh and even more negative in his opinions. Ambassador Kennedy told anyone who would listen, including American journalists, that Britain was not only losing the war but stood no chance of winning it. Britain’s only chance, he told a group of American officers, was for the United States to “pull them out.”

Some opposed helping Britain because “the damn Redcoats” had been America’s traditional enemy for generations, or because they saw the war against Hitler as Britain’s war and not theirs. But the most popular sentiment was pure isolationism, which is deeply ingrained in the American character—whatever the British do, 3,500 miles away, is none of our concern.

Churchill Aims To Change U.S. Opinion

This attitude was not just a matter of public opinion, but also was official policy. In July 1940, when the battle was just beginning, the United States was still bound by two of the three neutrality acts that had passed Congress between 1935 and 1937. These had been designed to keep the country from involvement in any “entangling alliances,” to use Thomas Jefferson’s phrase, and were very popular with the vast majority of Americans. (The act that prohibited the sale of U.S. arms and munitions to a “belligerent nation,” as well as the use of American ships to carry them, was repealed in 1939.) Generally, the country wanted nothing to do with the European war, and still had two neutrality acts that legalized this point of view.

Churchill was determined to change America’s opinion. A British writer said that Churchill was “obsessed with getting America into the war.” Churchill may or may not have been obsessed, but he was certainly resolved that the defiantly neutral—and sometimes blatantly anti-British—Americans would have their viewpoint turned around.

At first, Churchill tried to frighten Roosevelt with the prospect of an early German victory and what that would mean to the United States. But he soon gave up that idea when he realized that if Americans thought that the Germans would win, they would be even less inclined to back Britain’s war effort. So Churchill and the Ministry of Information decided to use the opposite approach: create the myth of “Their Finest Hour”—the gallant young pilots of the RAF fighting the ruthless Hun and shooting him down in record numbers. The Ministry of Information gave American reporters all the help they needed and made certain that censors were on hand to give stories a pro-British slant.

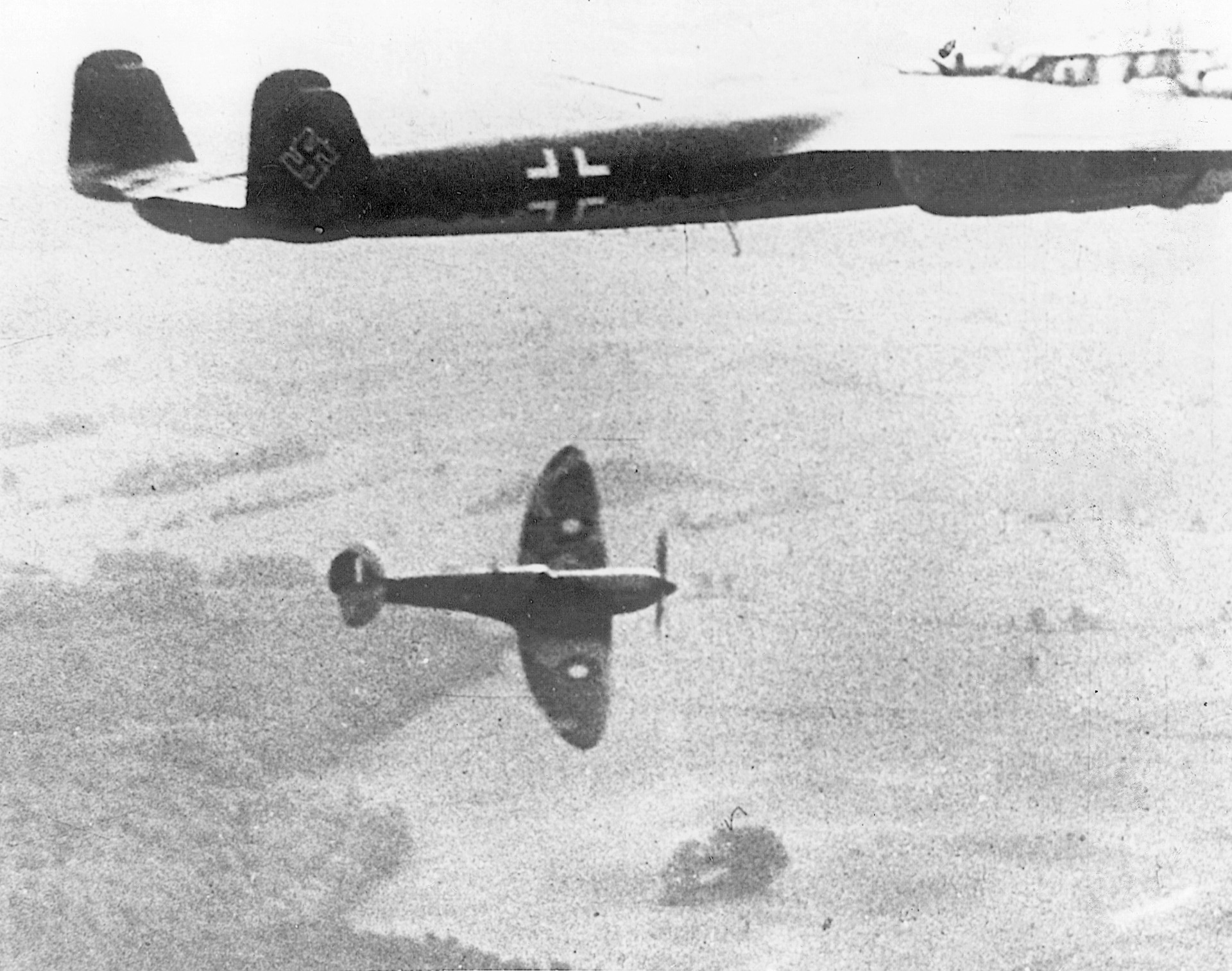

The first “official” day of the Battle of Britain was Wednesday, July 10, 1940. For the next month, the Luftwaffe attacked British shipping. RAF Fighter Command’s Spitfire and Hurricane pilots came up to protect the coastal convoys, which sailed from the Thames Estuary through the Straits of Dover.

Both the Luftwaffe and the RAF spent the month getting the measure of each other—each other’s aircraft, each other’s tactics, each other’s strengths and weaknesses. The Spitfires and Hurricanes turned out to be much more advanced than any fighters the German pilots had encountered so far. During the first 13 days of the battle, the Luftwaffe lost 82 aircraft of all types, including bombers, while the RAF lost 45 aircraft, mostly fighters. But although the Luftwaffe was suffering more losses, the RAF was having its fighters shot down at an alarming rate. British writer Len Deighton noted that RAF losses were occurring at such a rate that “Fighter Command would cease to exist within six weeks.”

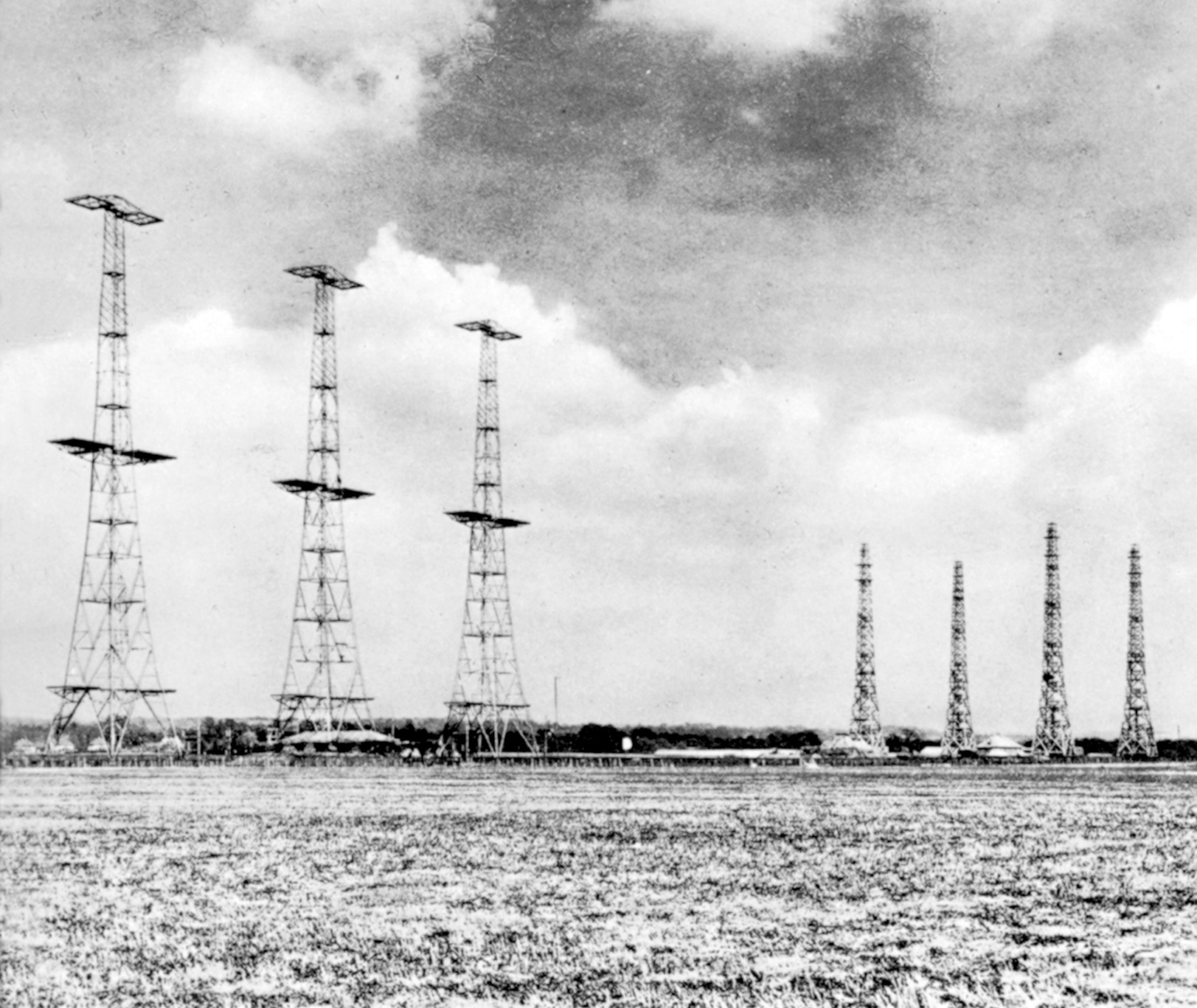

Losses would have been far worse if not for Britain’s Chain Home RDF system (for Radio Direction Finding, later changed to “Radar”), which detected German aircraft while they were still gaining height over France. Twenty-nine CH stations stretched from the east coast of Scotland to the west coast of Wales. Each of these could detect an airplane at a range of about 120 miles. Chain Home Low stations, which used a shorter wavelength than CH stations, were able to plot low-flying aircraft about 50 miles from the coast.

The CH network gave RAF Fighter Command a vital edge over the Luftwaffe. By keeping track of the height, range, and course of an incoming raid, the radar stations eliminated the need for fighter pilots to fly standing patrols. These CH stations were also a constant source of frustration for German pilots. Whenever they approached the coast, with rare exceptions, the Spitfires and Hurricanes were always there to meet them. No one, including Luftwaffe Commander-in-Chief Hermann Göring, knew exactly how these radar stations operated, but everyone knew where they were located—the 350-foot-tall aerials were visible to anyone on the French coast with a pair of binoculars. Göring agreed that the stations should be put out of action and ordered a change of targets—from shipping in the Channel to the CH stations and Fighter Command’s sector airfields.

Battle, Public Opinion Setbacks Suffered

The Battle of the Channel, der Kanalkampf, had not been a clear-cut victory for the Luftwaffe, but it did give the German Air Force a decided edge. During July and early August, the RAF lost 148 aircraft, along with many veteran pilots. The aircraft could be replaced—Lord Beaverbrook, the Minister of Aircraft Production, was doing an outstanding job in supplying the depleted squadrons with replacement aircraft—but there could be no mass production of replacement pilots. The new pilots from training units may have been enthusiastic, but they were also inexperienced.

The other battle, the effort to sway the American public to Britain’s side, was also not going as well as Prime Minister Churchill would have liked. The American news media continued to broadcast stories about the air war over southern England, and most Americans were interested in hearing about this new kind of warfare. But the general opinion toward the war had not changed during July. The vast majority of Americans still preferred to remain neutral.

For both the Luftwaffe and the RAF, the middle of August would begin a new phase of the Battle of Britain. The battle would now be one of attrition against Fighter Command. From August 12, the fighter airfields and CH warning system would come under direct attack. In Directive No. 17, which had been issued on August 1, Adolf Hitler declared his intent “to intensify air and sea warfare against the English homeland.” Specifically, he ordered:

1. The Luftwaffe is to overpower the Royal Air Force …

2. After achieving temporary, or local, air superiority, the air war is to be carried out against harbors …

After these two items had been accomplished, “The Luftwaffe is to stand by in force for Operation Sea Lion.”

“Führer Has Ordered Me To Crush Britain”

Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring was enthusiastic about his new assignment. He thought it was fitting to his rank and station in the Nazi regime. He called a meeting of senior Luftwaffe commanders at The Hague to discuss the impending battle. “The Führer has ordered me to crush Britain with my Luftwaffe,” he said. “By delivering a series of very heavy blows, I plan to have the enemy, whose morale is already at its lowest, down on its knees in the nearest future so that our troops can land on the island without any risk.” Göring believed that the RAF pilots were not as good as his, in spite of the fact that Fighter Command had been giving a good account of itself for the past several weeks, and in spite of the fact that his senior commanders assured him that this was not true. The Reichsmarschall had a tendency to believe his own propaganda, which was one of his many failings as Luftwaffe Commander-in-Chief.

The next phase of the battle began on August 12. The first attacks came in the morning, mostly by bomb-carrying Messerschmitt Bf-110 twin-engine fighters and Junkers Ju 88 medium bombers, and were directed at CH stations at Pevensey, Rye, Dover, and Ventnor on the Isle of Wight. Ventnor was knocked out for several days; the other three were badly damaged and could operate only at a reduced capacity. Because of the resulting gap in the CH network, the next attack, which began at about 1:30 pm, arrived over the coast of Kent without much advance warning.

In the ensuing attack, the RAF fighter airfields at Hawkinge, Lympne, and Manston suffered major damage. Manston was a forward airfield, right on the channel coast, and was an easy target. It came under attack while the airfield’s fighters were scrambling to intercept. When one of the airfield pilots landed to re-fuel, he discovered that Manston “was a shambles of gutted hangers and smouldering dispersal buildings, all of which were immersed in a thin film of chalk dust that drifted across the airfield.”

This was the Luftwaffe’s procedure for the next week and a half—hit the radar stations to blind and confuse the defenses, and then overwhelm the RAF fighter airfields with mass attacks. The Luftwaffe suffered its share of losses during these attacks—on August 15, the RAF claimed 182 German aircraft destroyed. (This was later reduced to 75; German sources insist that the real number is closer to 55.) Official RAF losses were 34 destroyed.

But the damage being inflicted upon RAF fighter bases was severe, and would be felt for some time to come. Bomb craters could be filled in quickly enough, but damaged and destroyed hangars, repair shops, and other facilities could not be fixed as easily. The efficiency of the fighter airfields began to deteriorate, and would continue to decline with each raid by the Luftwaffe.

Attacks Taking Their Toll On RAF

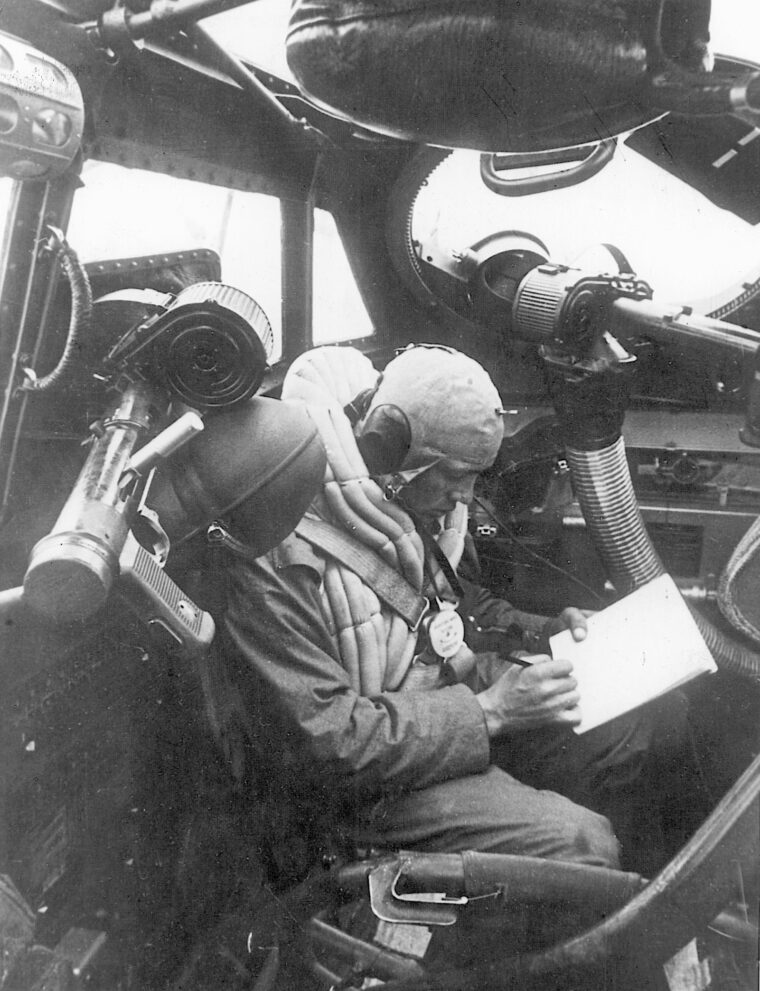

Pilot efficiency had also begun to decline. The air battle on August 15 lasted nine hours and was scattered over hundreds of miles—there had been six major attacks, along with several smaller skirmishes. The pilots, scattered throughout southern England, made repeated interceptions—being scrambled for an incoming attack, landing for rearming and refueling, and being scrambled again for another raid. Alan Deere of 54 Squadron flew a total of six sorties during these nine hours, an average sortie lasting about 40 minutes.

It was becoming obvious the pilots could not go on like this. The Luftwaffe’s campaign to cripple RAF airfields was only four days old, and the pilots were already beginning to lose some of their concentration. This loss would affect the pilots’ performance in combat and would cause the death of some of them.

On August 16, Luftwaffe losses came to 45 aircraft; the RAF lost 21. But RAF Fighter Command was wary, despite the encouraging numbers. “In spite of heavy losses,” RAF Intelligence warned, “large scale attacks by GAF [German Air Force] on airfields and industry are likely to continue.” The report went on to predict that the Luftwaffe “probably underestimates considerably our own losses,” and also forecast that “GAF is prepared to suffer heavily in the attempt to obtain air superiority.”

In the House of Commons on August 20, Prime Minister Churchill gave a fairly optimistic evaluation of the battle. “The enemy is, of course, far more numerous than we,” he said, but went on to assure his audience that “our bomber and fighter strengths now, after all this fighting, are larger than they have ever been.” He added that “American production is only just beginning to flow in,” and predicted that Britain would be able to hold off a German invasion if the RAF could stop the Luftwaffe.

Churchill concluded by telling the Commons that the gratitude “of every house in our island, in our Empire, and indeed throughout the world” went out to the RAF fighter pilots. He concluded his address: “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.”

This sentence has become one of the set phrases of modern history, and has entered the literature of the English language. But at the time, it launched a thousand irreverent wisecracks, especially among the RAF. “He must be thinking of our liquor bills,” was one quip. Other gems included: “He must mean our back pay,” and “He must be talking about my ex-wife’s brassiere size.” Referring to his flying officer’s pay of 14 shillings and sixpence per day (72 1/2 pence in the new currency, or about $1.20 U.S.) Michael Appleby of 609 Squadron added, “and for so little.”

Speech Makes An Impression In America

Churchill’s famous words were also reprinted in the United States, where they made a considerable impression, especially among those who favored sending aid to Britain. It was a good deal more moving than the Ministry of Information’s (MOI) inflated figures on German aircraft losses.

American correspondents dutifully reported the numbers they had been given by the Ministry, but they were not inclined to believe them. Some of the more intrepid (or foolhardy) reporters tried to track down every German airplane reported as shot down, but could not hope to locate all the wrecks. Most gave up after finding only one or two—after tripping over fences, wading through streams, and driving all over southern England.

Much of the American public did not believe the figures, either. “If the Germans keep losing so many planes,” a New Jersey teacher asked, “how come they keep coming back for more every day? If they really lost as many as the British claim, they would be out of the war by now.” Instead of convincing the American public that Britain was winning the war, the MOI’s overblown numbers were having the opposite effect—Americans were beginning to believe that the wily Brits were inflating the enemy’s losses for the purpose of covering up their own.

On August 19, Göring made a decision that would alter the outcome of the battle—he ordered attacks on the CH stations to stop. Not one of the tall RDF masts had been destroyed, which came as a major disappointment. It turned out that the towers were immune to anything except a direct hit—blast waves passed right through the latticework of the aerials without causing any visible damage. Because there was no apparent damage in any of the photo-reconnaissance pictures, Göring came to the conclusion that bombing them was a waste of time and ordered the bombing attacks to be discontinued.

This decision revealed an almost total ignorance of radar and what it could do (and had been doing). Had he been more technically minded, Göring would have ordered the attacks intensified, to knock out the buildings nearby that held the bulk of the communications equipment. His order, based upon a total disregard of technical knowledge, would cost the Luftwaffe dearly in the coming weeks.

Göring’s primary target would now be the RAF fighter bases. His goal was to force Fighter Command to abandon its bases in Kent, Sussex, and Surrey, which would leave the approaches open to anything the Luftwaffe wanted to attempt. The first day of the change in tactics would be Saturday, August 24.

Chain Home stations began plotting a large raid over France at about 9 o’clock that Saturday morning. The bombers attacked the airfields at Hornchurch, Essex, north of the River Thames; North Weald, also in Essex; and Manston. Hornchurch escaped with relatively little damage, mainly because heavy antiaircraft fire caused the bombers to scatter and to miss their targets. But Manston was destroyed.

About 20 Junkers Ju-88s attacked Manston without any fighter opposition and left it, according to Peter Townsend, commander of 85 Squadron, “a shambles of wrecked and burning hangars, a wilderness strewn with bomb craters and unexploded bombs.” As soon as the raid ended, workmen began clearing away the rubble and repairing the damage—ignoring the unexploded bombs while filling in craters only a few feet away and mending the main telephone and teleprinter cables.

They might just as well have saved themselves the trouble. At about 3 o’clock that afternoon, another attack hit Manston. The landing field was once again cratered by bombs, and all telephone cables were blown up for the second time that day. All contact between Manston and Headquarters at Uxbridge, Middlesex had been severed again. Almost all the buildings at the airfield, including living quarters, had been damaged; some had been destroyed by bomb blast.

When communications were restored—for the second time since 9 am—the airfield commander received an order to evacuate Manston. Fighter Command decided that the base was too vulnerable. Because it was in a virtual state of ruin, there was no point in keeping the base operational. In future, Manston would be used only as an emergency field.

Göring’s plan had been in effect for less than a day, and one of Fighter Command’s most forward bases—Manston was situated on a cliff next to the Channel—had already been abandoned.

The Luftwaffe kept up its attacks on RAF fighter airfields for the next two weeks. Hornchurch, Kenley, and Biggin Hill were bombed repeatedly. By August 30, several buildings at Biggin Hill were so severely damaged by bomb blast that they were declared unsafe. Power, gas, and water mains were cut, along with telephone cables. The airfield was cut off from communicating with the outside world, including its own fighter squadrons. Maintenance crews had Biggin operating again by the following day, but at greatly reduced capacity.

The day’s losses for August 30 came to 36 aircraft for the Luftwaffe and 24 for the RAF. Eleven RAF pilots were killed. But, for the RAF, even more ominous than the number of pilots lost was the fact that the Luftwaffe’s attacks were not being stopped. The bombers were penetrating the defenses and getting through to their targets, which were mainly Fighter Command’s airfields.

The battle was not proving to be easy for either side—the Luftwaffe and RAF were too evenly matched for that. But the fighting had unmistakably tilted in favor of the Luftwaffe. The RAF was losing too many aircraft, far too many pilots, and was no longer able to defend its airfields or any objective that the Luftwaffe chose to attack.

Aircraft Losses Overtaking Production

On August 31, the Luftwaffe began at about 8 am and continued its unrelenting attacks on Fighter Command’s airfields: North Weald, Croydon, Biggin Hill, Hornchurch. In the early afternoon, Croydon and Biggin Hill were bombed again. Hornchurch and Biggin Hill were probably hardest hit. At Hornchurch, the attack began at 1:15 pm, when Dornier twin-engine bombers of Kampfgeschwader 3 dropped about 60 bombs on the airfield. Biggin Hill’s attack began later and very nearly put the airfield out of action.

By September 1, Biggin Hill was finished as an effective fighter base. Gas and water mains had been shattered; all telephone lines except one—out of 30—had been cut. The airfield’s operations room had to be transferred to a base in Biggin Village. Only one squadron, 79 Squadron’s Spitfires, could now be serviced by the airfield’s facilities, instead of the usual three squadrons. So many buildings had been smashed by the daily bombings that some WAAFs (Women’s Auxiliary Air Force) had to be billeted in town—to the annoyance of some of the residents. If Winston Churchill had not pledged not to abandon any more fighter bases, the airfield would have been evacuated, like Manston.

The Chain Home stations were plotting the incoming raids, but the Luftwaffe was able to push its way through to their targets in spite of the advanced warning. By the beginning of September, Spitfires and Hurricanes were being shot down in ever-increasing numbers. For the first time since the battle began, aircraft losses were overtaking production—the German pilots were shooting them down faster than Lord Beaverbrook could manufacture them. Even more ominous for the RAF, trained pilots were being killed and badly wounded at such a rate that the practice of rotation—transferring squadrons to a quiet area after a period in combat—was in jeopardy.

And as desperate as the pilot shortage was at the end of August, it looked to become even worse in the near future. RAF Fighter Command decided to look for pilots outside of its own training units. The following notice began to appear in American newspapers during July and August. (This particular advertisement appeared in the New York Herald Tribune):

“LONDON July 15: The Royal Air Force is in the market for American flyers as well as American airplanes. Experienced airmen, preferably those with at least 250 flying hours, would be welcomed by the RAF.”

Fighter Command had acquired some pilots from occupied countries: Belgians, French, Czechs, and Poles. The problems was that there were so few of them—only 12 French pilots and 29 Belgians managed to escape to England. And these pilots also had their drawbacks. Many were not accustomed to advanced fighters like the Spitfire and Hurricane. Most had flown out-of-date biplanes without retractable landing gear, which is one reason that the Luftwaffe had enjoyed such success. After giving an expert demonstration of rolls and loops, these foreign pilots would sometimes wreck their planes when they forgot to lower their wheels before landing.

Another drawback was language difficulties. The Poles, for instance, were among the best and most determined in Fighter Command. But no one could communicate with them; they did not understand ground controllers and could not be vectored to intercept an incoming enemy raid. Before they could be classified as operational, the Poles would at least have to learn the basic rudiments of English. Also, they had to learn flight jargon, such as “angels,” “vector,” “bogey,” and “bandit.” Without the ability to communicate with ground control, the Poles were as good as useless, in spite of their experience and skill.

This is one of the reasons that Fighter Command decided to accept American volunteers. The Yanks might not have the combat experience of the Poles or the Czechs, but at least they spoke a language that was roughly similar to English. They could be vectored toward an incoming enemy formation by ground control, and could sometimes even be understood when they spoke. (They would also prove useful as a propaganda device, to sway the opinion of neutral America.)

Nobody knows how many “secret Americans” served in the Royal Air Force during the summer of 1940, or how many of the “Canadians” who joined the RAF were actually Americans. The editors of the Battle of Britain Then and Now give the number of U.S. citizens who took part in the battle as 11. The official number is 7: Pilot Officer Arthur Donahue, 64 Squadron; Pilot Officer J.K. Haviland, 153 Squadron; Pilot Officer W.M.L. Fiske, 601 Squadron; Pilot Officer Vernon Keough, 609 Squadron; Pilot Officer Phil Leckrone, 616 Squadron; Pilot Officer Andrew Mamedoff, 609 Squadron; and Pilot Officer Eugene Tobin, 609 Squadron. But the real figure is probably many times higher. The only trace of their true nationality is buried in squadron rosters— “Tex” or “America” or “Uncle Sam.”

One of the neutrality acts made joining the armed forces of a “belligerent nation” a criminal offense. The punishment for anyone unfortunate enough to be caught trying to join the RAF was stiff—a $20,000 fine, a 10-year prison sentence, and loss of U.S. citizenship. To protect themselves from harassment by border patrols and the FBI, American volunteers simply declared themselves to be Canadian. Others simply went to Canada and disappeared. A volunteer from New York told a customs officer that he was going to Newfoundland “for some shooting.” Americans who crossed into Canada and made their way across to England and the RAF lost their U.S. citizenship and technically became fugitives from justice.

Between June 1940 and December 1941, several hundred Americans volunteered to join the RAF. The best known are the fighter pilots, but others served in Bomber Command as pilots, navigators, and air gunners. Among those who are known to have served with Fighter Command in the summer of 1940 was Flt. Lt. James Davies of Bernardsville, NJ, who joined the RAF in 1936. By June 1940, he had shot down six enemy aircraft and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. On June 25, the day on which he was to have received the DFC from George VI, Davies was shot down and killed. (He is not listed as one of the seven “official” Americans in the Battle of Britain because he was killed before the officially recognized start of the battle, July 10.)

The best known, and most aggressively publicized, of all the Yanks in the RAF was Pilot Officer Billy Fiske. Chicago-born William Meade Lindsley Fiske III was one American who made no secret of his U.S. citizenship—he had enough money and social connections to ignore both the Neutrality Act and its consequences. He was the son of an international banker and had attended Cambridge University. After leaving Cambridge, he lived a life of leisure, became a champion bobsledder, and entered British society when he married the former wife of the Earl of Warwick. Fiske settled in England, where he did weekend flying in the 1930s. Because of his influential friends and family connections, he had no trouble at all joining the RAF Auxiliary in 1940.

American RAF Volunteer’s Death Gets Publicity

On August 16, Fiske’s Hurricane was hit by enemy fire, but he was able to crash-land at Tangmere, 601 Squadron’s base in Sussex. He was burned on the face and hands, but did not seem to be seriously injured. The next day, however, he unexpectedly died of shock.

Fiske’s obituary in The London Times of August 19 ran for 39 lines—highly unusual for such a junior officer. (The U.S. Air Force equivalent to Pilot Officer is 2nd Lieutenant.) The standard obituary for officers was seven or eight lines; senior officers sometimes received 15 or 20 lines. The reason that Fiske was given so much space was mainly because he was American. His death in combat with the Luftwaffe presented Britain with a golden opportunity. Now that a well-known American citizen had been killed in the battle, Winston Churchill, speaking through the Ministry of Information, could tell Americans that their fellow countrymen were already involved in the war. American newspapers also carried stories about Billy Fiske’s funeral—LIFE magazine ran a full-page photo spread. Fiske’s death was highly publicized and made into a top propaganda item to arouse American sympathy for Britain.

A great deal of time and effort has been spent to determine whether or not Billy Fiske was the first American to be killed in World War II. He was certainly the first “official” American to be killed. Flight Lieutenant Jimmy Davies of Bernardsville, NJ, died on June 25, a month and a half before Fiske, which may have been overlooked. (He was also killed before the battle officially began on July 10, which may have had something to do with it.) Some U.S. citizens who volunteered for the RAF as Canadians may have lost their lives even earlier, but because they kept their nationality a secret, no one will ever know for certain.

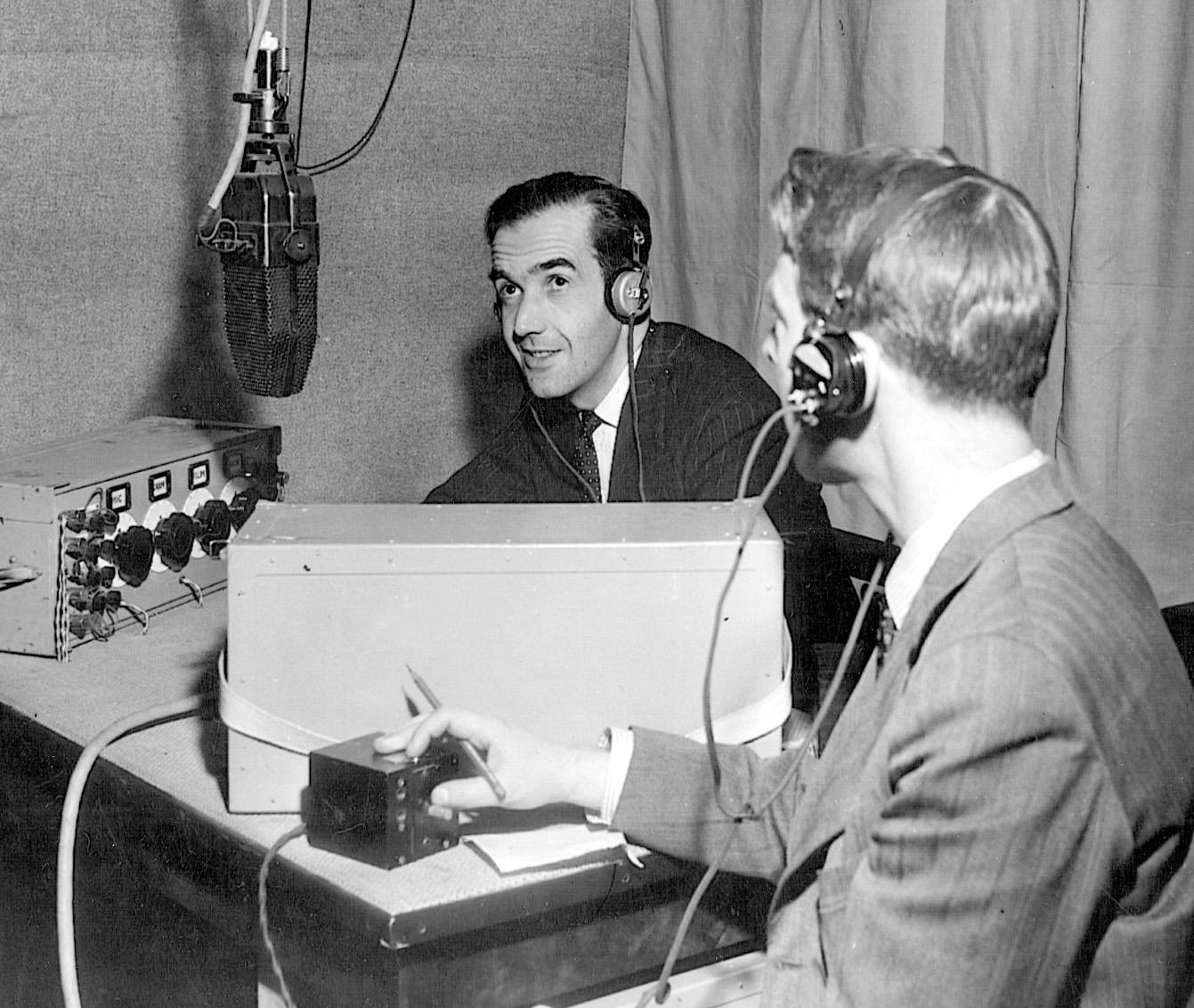

American reporters from all the major news services, as well as most of the leading American newspapers and broadcasting services, went on filing their stories about the strange new war that was being fought—hundreds of feet above southern England by a relative handful of men. By the beginning of September, most American journalists had given up on Britain and the RAF, and Winston Churchill’s plan of allowing American newsmen to report the battle seemed to be backfiring. They could see for themselves which way the battle was going. Edward R. Murrow of the Columbia Broadcasting System was, in the words of his wife Janet, “one of the few who felt that somehow, by some miracle, they were going to win.” Most of Murrow’s fellow reporters would have agreed that the RAF needed nothing short of a miracle.

Reporters in England were not the only ones who had given up; many in the United States also had little hope. Newsman Vincent “Jimmy” Sheehan was asked to write a 25,000-word magazine article describing the entry of German forces when they occupied London. But Sheehan turned down the offer—when Hitler arrived in London, he did not want to be there.

Air Chief Marshal Sir High Dowding, Commander-in-Chief of Fighter Command, also grasped the situation. He saw that his fighter squadrons were stretched to the limit, and that the Luftwaffe was having no trouble bombing its targets in spite of RAF interceptions. “The last week in August and the first week in September—these two weeks were the worst for us,” recalled Dowding’s personal assistant. “Fighter Command was nearly on its knees … [Dowding] wondered how much longer he could hold out.”

Since August 24, Fighter Command’s airfields had taken a severe and steady pounding. Its fighter strength had been severely depleted, and its pilots had been decimated. A British historian wrote, “The battle in the air … was being decisively won by the Luftwaffe. If this continued, there would be no fighters left, or at any rate not enough to put up an effective defence.” Dowding knew the situation and the desperate crisis faced by Fighter Command better than anyone else.

Then on August 24 came an accident that would alter the course, and the eventual outcome, of the Battle of Britain. The Luftwaffe had sent a night raid against the oil tanks at Purfleet and Thameshaven, miles downriver from London. But the lead navigator lost his way, and the bombers overflew their target and unloaded over various sections of London. Bombs fell on several districts of the capital, including Islington, East Ham, Stepney, and Bethnal Green. One bomber released over the ancient city district, causing damage that received the most publicity throughout Britain as well as in the United States.

It had all been a mistake. Hitler did not order an attack on London. In fact, he expressly prohibited London from being bombed. But Winston Churchill did not know or care whether or not the attack had been a mistake. London had been bombed; Churchill wanted to hit back. He sent a note to his Chief of Air Staff, Sir Cyril Newall: “Now that they have begun to molest the capital I want you to hit them hard, and Berlin is the place to hit them.”

A reprisal raid for the Luftwaffe’s accidental bombing of London was carried out by RAF Bomber Command the following night, when 81 bombers attacked Berlin. Two nights later, a second, slightly heavier raid attacked Berlin again. These two bombing attacks came as a genuine shock to Berliners—Reichsmarschall Göring had promised them that they would be safe from enemy air attacks, and the RAF had bombed them twice within a week.

As Luftwaffe Commander-in-Chief, Göring felt humiliated by the raids. The damage inflicted had not been significant, especially when compared with what was to come, but 10 civilians had been killed in the August 28 attack. The two bombings shook the complacency of Nazi officials, who had believed Göring’s promise that Germany would never be attacked by enemy bombers. Hitler was also angered that the RAF had been able to carry out their air raids, two of them in the same week.

Göring Makes London Top Target

Göring decided that he would retaliate by bombing London. Other British cities had already come under attack by Luftwaffe night raids: Birmingham, Manchester, Sheffield, Coventry, and Liverpool all had been bombed during late August and the first days of September. But Göring did not want just a few token raids against London. On September 3, he told his senior commanders that he had decided a complete change in tactics—from that day, the Luftwaffe’s main attack would be switched from Fighter Command’s airfields to London.

Göring was actually in no condition to make such a decision. His nurse reported he was in a state of nervous exhaustion; no major judgment should have been attempted while he was in that state. In addition, he was under the influence of paracodeine and other drugs—Göring had been a drug addict since the 1920s—which further interfered with his powers of reason. But while he was in this medical and emotional condition, he made a major decision that would have far-reaching consequences.

Göring, of course, could not have carried out his plan without Hitler’s endorsement, and Hitler agreed with Göring’s decision. He also wanted to bomb London in retaliation for the RAF’s bombing of Berlin, and allowed himself to be convinced that attacking London would shorten the battle. Göring explained that forcing the Spitfire and Hurricane squadrons to defend their capital city would lead to increased losses by the RAF. He believed that most British fighter squadrons were not only badly depleted, but were on the brink of annihilation, and that the Luftwaffe would be able to destroy RAF Fighter Command if the enemy could be pressured into combat. To Hitler, bombing London not only made good military sense, but also appealed to his sense of drama and revenge.

Hitler announced this change of strategy on the evening of September 4, in a speech at Berlin’s Sportspalast. After beginning with a few unfriendly remarks about Winston Churchill, and assuring his audience that he intended to invade England, he came to his main topic. “You will understand that we are now answering night for night. And when the British Air Force drops two, or three, or four thousand kilograms of bombs, then we will drop 150, 230, 300, or 400 kilograms in one night.” After the applause died down, Hitler continued, “When they declare that they will increase their attacks on our cities, then we will raze their cities to the ground!” The speech was broadcast two hours later.

The first of the Luftwaffe’s mass raids on London, which became known as “the Blitz,” took place on Saturday, September 7. RAF fighter squadrons had been positioned to protect their airfields, but it soon became apparent that the Luftwaffe were not headed for the fighter airfields—their target was London. The German bombers were able to reach London without any interference and began their attack just after 5 pm. Most of their bombs landed on the docks and densely populated areas of east London. After dark, the Luftwaffe returned. The fires started in the afternoon made a brilliant aiming point for the bombers.

For the next eight hours, from 8:20 pm to 4:30 am, about 450 bombers dropped over 300 tons of high explosives and 400 canisters of incendiaries over London’s East End. Well over a thousand fires were started. In the district of West Ham, entire streets disappeared in the fires. A school was taken over as a shelter for those who lost their homes. But the school was also bombed, killing 450 of the homeless.

In spite of the civilian deaths in east London, the bombing of the capital was giving Fighter Command a desperately needed respite. To Air Chief Marshal Dowding, the attacks on London brought hope. If the Luftwaffe kept bombing the city, it would have to leave his airfields alone; which meant that his fighter airfields, including Biggin Hill and Tangmere, could be repaired and restored, and his depleted squadrons would have time for rest and reinforcement.

For the next week, the Luftwaffe’s main objective continued to be London. RAF fighter airfields received only nuisance raids. The bombing campaign against London was doing real damage to the city, but was not paving the way for the invasion of England and was not doing anything toward destroying Fighter Command. While the Luftwaffe bombed London, the RAF fighter squadrons were replenishing the losses they had suffered during the past weeks.

On September 15, the Luftwaffe sent 200 fighters and bombers to London just before noon. Spitfire and Hurricane squadrons harassed them all the way to their targets and all the way back to the Channel coast. The second attack of the day began at about 2:15 pm. This raid was also overwhelmed by RAF fighters; the bombers, as well as their fighter escort, encountered ferocious resistance. The Luftwaffe pushed its way through to London, but suffered heavy losses.

Hitler Indefinitely Postpones Invasion

The RAF claimed 185 German aircraft destroyed for the day. Postwar British records give the total as 60; the German total is 56, with two missing. But 185 sounded a lot more impressive, and was the figure released by the Ministry of Information. Newspapers and magazines on both sides of the Atlantic dutifully accepted the MOI’s figure and published the story that 185 German planes had been shot down.

In Britain, September 15 would be commemorated as Battle of Britain Day and acknowledged as the turning point of the battle as well as one of the decisive points of the war. The fighting on that Sunday convinced the Luftwaffe that RAF Fighter Command was far from being destroyed and appeared to be stronger than ever. Two days later, Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of England postponed indefinitely.

The Battle of Britain went on for another month and a half, until October 31, with heavy fighting continuing throughout September—on September 27, the Luftwaffe lost 55 aircraft, while the RAF had 28 of its fighters destroyed. In addition, the bombing of London would continue until May 1941, the city being attacked every night for 57 consecutive nights between September 7 and early November.

Meanwhile the propaganda battle against isolationist America was as important as the fighting with the Luftwaffe, and was also in full fury.

Churchill’s campaign was having its desired effect. Americans were being convinced that the British were able to hold their own against the Germans, although they were still unwilling to send aid or assistance. The goal was now to show Americans that Britain’s war against Nazi Germany would soon be America’s war, and that it would be in the best interests of the United States to send Britain as much materiel—and soldiers—as possible. Churchill was still determined to turn American opinion to Britain’s side. He had a great deal of help from his MOI, as well as from American reporters and broadcasters.

Many highly influential reporters—including Raymond Daniell of The New York Times, Quentin Reynolds of Colliers magazine, and Edward R. Murrow of CBS radio—were outspoken interventionists. They believed that Britain deserved the full backing and support of the United States. They also let their millions of readers and listeners know their feelings, in a highly effective manner. These journalists willingly served as Churchill’s propaganda ministers to America.

Through his now-legendary broadcasts from London, Edward R. Murrow made it clear that Britain’s position was perilous, but that the British were standing up to the Germans. His tone was always matter-of-fact, and he made Londoners seem heroic by understating their situation. During the broadcast of Saturday, September 24, Murrow described an air raid as it was happening; his listeners actually heard the engines of the German bombers, the antiaircraft fire, and the exploding bombs as Murrow calmly described the raid. “I am standing on a rooftop overlooking London,” he said from the roof of Broadcasting House. “You might be able to hear the sound of guns in the distance, very faintly, like someone kicking a tub.”

A moment later, he told his audience how the local searchlights were trying to pinpoint the German bombers in his area. “More searchlights spring up over on my right,” he said. “I think probably in a minute we shall have the sound of guns in the immediate vicinity. The lights are swinging over in this general direction now. You’ll hear two explosions. There they are! … Just overhead now the burst of antiaircraft fire.”

Murrow Warns About Losing Britain

Every night, Murrow delivered his subtle message from London to millions of Americans: The British were fighting for their lives, and must not be abandoned. If Britain lost, what was now happening to London might happen to New York in the not-too-distant future. Winston Churchill realized that these broadcasts did more to sway American opinion than all the Ministry of Information propaganda put together.

Writer and reporter Quentin Reynolds was a friend of Murrow’s, but friendship was the only thing they had in common. Their styles were completely different. Reynolds’ accounts were blatantly pro-British and anti-German; he made no attempt at subtlety or objectivity. In every one of Reynolds’ stories, the Germans were clearly the villains, and the British were noble underdogs, richly deserving of American support.

One of Reynolds’ stories involved the night his apartment building was hit by a bomb. He made the incident seem like a nonevent: “If this is the best old Jerry can do,” one of his characters says, “we’ve got nothing to worry about.” This was Reynolds’ line: old Jerry was doing his worst, but it would do him no good in the end. According to Reynolds, the bombers “scored a direct hit on a school, and a great many children … had been killed. They hit a hospital, and thirty women had been killed.” The Ministry of Information could not have come up with a better story for American consumption—the Germans bombing schools and hospitals—if they had written it themselves.

Hitler may not have read Quentin Reynolds’ stories, but he knew all about them, as well as about Edward R. Murrow’s broadcasts. His Ministry of Propaganda kept him well informed. He also knew that this information was turning Americans against Nazi Germany. By the time the Battle of Britain was winding down, Hitler realized that the United States was his enemy or, as one writer put it, “a neutral with no pretense of neutrality.” Britain’s propaganda campaign was doing everything Churchill wanted, slowly but surely.

At the outset of the battle, 64 percent of Americans polled said that they were against sending aid to Britain in any form—they did not know very much about the fighting in Europe and were not interested. But in November, a few days after the official end of the battle, 60 percent of Americans told the same poll that they were now in favor of sending help—even if it meant that the United States would get involved in the war as a result.

The most immediate result of this propaganda victory was the passing of the Lend-Lease Bill. Lend-Lease was introduced in Congress in mid-December 1940 and voted into law early in 1941. Franklin D. Roosevelt now had the authority to aid “any country whose defense the President deems vital to the defense of the United States.” In July, before Churchill’s media blitz, it never would have passed, not in the country’s isolationist mood. If the public’s feeling had not changed, Roosevelt would never have introduced the bill. He was politician enough to have known Abraham Lincoln’s adage on public opinion: You can do anything with it and nothing without it.

Churchill’s media campaign was carried out with the full cooperation of the American press. The broadcasts of Edward R. Murrow, the stories of Quentin Reynolds, and the reports of Raymond Daniell and his colleagues all gave the American public the word on German aggression: If Britain lost the battle, sooner or later the United States would have to face Hitler alone.

Hitler was outraged by this change in American opinion. When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Hitler did not know exactly what to do. His generals and military advisers urged him to remain at peace with the Americans—Germany already had a two-front war with Britain and the Soviet Union. Hitler reminded his generals of the Tripartite Pact, which had been signed on September 27, 1940 by Germany, Japan, and Italy and bound the three countries together in a mutual defense agreement. Japan was at war with the United States, Hitler said, therefore Germany must declare war on America, as well.

But the Tripartite Pact specifically stated that Germany was bound to come to Japan’s aid only if Japan had been attacked. Because Japan had instead attacked the United States, Germany was under no obligation to come to Japan’s assistance.

Hitler was well aware of the particulars of the pact, but as far as he was concerned, the United States had been at war with Germany for a year and a half. America had passed Lend-Lease, giving materiel to the British; American pilots flew with the RAF against his Luftwaffe; and the general attitude of Americans had become more sympathetic toward Britain and hostile toward Germany. His resentment had been building since the summer of 1940. So in December 1941, the Tripartite agreement gave him the excuse to release his pent-up frustration against the Americans.

“They have been a forceful factor in this war,” Hitler said, “and through their actions have already created a situation of war.” To his way of thinking, the United States had already attacked Germany. Now it was time to strike back. Churchill’s propaganda campaign to control American opinion; the efforts of Edward R. Murrow, Quentin Reynolds, and their fellow reporters to convince Americans that Hitler was an enemy of the United States; and the presence of Billy Fiske and the other American volunteers in the RAF had more of an impact than even Winston Churchill could have hoped for during the summer of 1940.

All these people and their varied activities did more than just convince Americans that Hitler was an enemy who would have to be faced. They also managed to convince Hitler of the same idea—that he would have to fight the Americans sooner or later in a full-scale war.

With the United States already at war with Japan, this seemed a golden opportunity for Germany. America would then be faced with a long, expensive, and very difficult two-front war, dividing American strength and resources. And so, on Thursday, December 11, four days after Pearl Harbor, Hitler opened formal hostilities against the United States. He went before the Reichstag and, in a bitter tirade against Franklin D. Roosevelt and the United States, demanded a declaration of war. In Washington, DC, Congress reciprocated on the same day. Germany and the United States were finally at war.

By declaring war, Adolf Hitler had simplified all of Winston Churchill’s problems. By this one act of anger and frustration, Hitler had done what Churchill had not been able to accomplish in a year and a half. Dean Acheson, who would become U.S. Secretary of State, thought that Hitler had played right into the hands of Churchill and the Allies. “At last,” Acheson said, “our enemies, with unparalleled stupidity, resolved our dilemmas, clarified our doubts and uncertainties, and united our people for the long, hard course that the national interest required.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments