By Pat McTaggart

May 1, 1944. Marshal of the Soviet Union Ivan Stepanovich Konev had a right to be pleased with himself and his men as he gazed at the maps spread before him.

Born in a small village in the province of Northern Dvina, Konev was conscripted into the Tsarist Imperial Russian Army in April 1916, but saw little action during World War I. During the Russian Civil War he served with distinction, becoming a political commissar. Graduating from the prestigious Frunze Military Academy in 1926, Konev served as a divisional and corps commander, escaping the massive purges that decimated the Red Army during the 1930s.

Soon after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Konev took command of the Western Front (the approximate equivalent of a German Army Group, containing anywhere from five to 12 armies). For the next two and a half years, he led various fronts in the war against Hitler, participating in the gigantic battle at Kursk and liberating the cities of Belograd and Kharkov. For his part in the encirclement and destruction of German forces in the Korsun-Cherkassy Pocket in February 1944, he was promoted to the rank of Marshal of the Soviet Union. Now, after years of bitter fighting, his 2nd Ukrainian Front stood poised in the Western Ukraine, ready to strike what was hoped to be a knockout blow against German forces in Southeastern Europe.

Konev’s 10 Armies Cut Through German Lines

Konev had 10 armies—the 27th, 40th, 52nd, 53rd, 4th Guards, 5th Guards, 7th Guards, 2nd Tank, 6th Tank and 5th Guards Tank—at his disposal. His armored forces numbered 650 tanks and self-propelled guns. On March 5, 1944, the 2nd Ukrainian Front launched an offensive against the German 8th Army northeast of Uman. The massed tanks and infantry of the 4th Guards, 5th Guards Tank and 2nd Tank Armies had little difficulty in slicing through the thinly held German line. Other armies soon followed, flooding through the breached German defenses.

When Uman fell on March 9, Konev ordered his forces to keep going toward the Bug River, giving the retreating Germans little chance to organize a defensive river line. His armies kept up the pressure, severing the 8th Army’s tenuous connection with the 1st Panzer Army. Other units, composed of mixed groups of tanks, infantry, and engineers, kept up their advance toward the Bug.

On March 11, elements of General S.I. Bogdanov’s 2nd Tank Army’s 16th Tank Corps (Maj. Gen. Dubovoi) reached Dzuhlinka and crossed the river, dashing any German hopes of holding the southern bank. A few hours later, the 29th Tank Corps (Lt. Gen. Kirichenko) of General A.G. Kravchenko’s 6th Tank Army took the river crossing at Gayvoron. With the main crossing clogged with armored vehicles and trucks, following Soviet infantry units confiscated boats or built rafts to get to the opposite shore. Once across, they spread out behind the mobile forces that were already heading for the next objective—the Dniester River.

Russians Halted by the Muddy Season

By March 15, Dubovoi’s corps had severed the Zhmerinka-Odessa rail line at Vapnyarka, a mere 30 miles from the Dniester. Two days later, Kirichenko’s corps reached the river and immediately established a bridgehead on the other side. Other units soon followed, and by March 21 the Soviets had firm control of the western bank.

For the next two days, Konev’s forces spread out through the Romanian countryside, meeting little opposition. As April approached, however, heavy rains began to fall, turning the ground and dirt roads into a brown quagmire that virtually stopped the Soviet mobile units dead in their tracks.

For Adolf Hitler, the “muddy season” meant that he would have time to stabilize his forces in Southeastern Europe. He was concerned about his wavering allies, Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary, which watched the Soviet advance with growing apprehension. On March 18, Admiral Miklós Horthy, the Regent of Hungary, succumbed to pressure from Hitler and allowed German troops to pour across the German-Hungarian border in what was essentially an invasion. Hungary’s oil fields were now under German control, but a larger prize lay in Romania.

The Ploesti oil fields, located about 30 miles north of Bucharest on the Wallachian Plain, were the center of Romania’s oil-refining industry. Without the fields, Germany would be hard pressed to find an alternative petroleum source for her industry and her military. Marshal Ion Antonescu, the head of Romania’s government, sent Hitler a pledge of loyalty on the day that German forces invaded Hungary. Some of Romania’s military leaders, however, were already in contact with the Soviets, hoping to negotiate a separate peace. The stalled Soviet offensive meant that more German troops could be sent to bolster Romania’s wavering military and to preempt any planned coup.

A Tall Order for the German Army

Hitler also planned to put a new, more loyal core of commanders in charge of his southeast flank. His personal airplane arrived at Field Marshal Ewald von Kleist’s Heeresgruppe A (Army Group A) headquarters on March 30. With von Kleist on board, the Focke-Wulf Condor aircraft then flew on to the city of L’vov to pick up Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, commander of Heeresgruppe Süd. The two men had borne the brunt of the Soviet assault in the Ukraine and Romania, and Hitler was furious that so much territory had fallen into Soviet hands.

Arriving at Hitler’s retreat in the Obersalzburg, von Manstein and von Kleist were brought before the Führer, who awarded both men the swords to the Knight’s Cross. He then relieved them of their commands. Newly appointed Field Marshal Walter Model replaced von Manstein, while Ferdinand Schörner, who would be promoted to colonel general on April 1, took command of Heeresgruppe A.

Before dismissing von Kleist, Hitler told him that the Soviet offensive had run its course and that he was certain the Red Army was exhausted. The Führer also said that after his forces in France threw the expected Allied invasion back into the sea, those divisions stationed in France would be sent to the East to reclaim the territory that had been lost during the previous year. In return, von Kleist simply told Hitler that the time had come to make peace with Stalin before the Eastern armies were totally destroyed.

When the new commanders arrived at their headquarters, the following order from Hitler, dated April 2, awaited them. “The Russian offensive in the south of the Eastern Front has passed its climax. The Russians have exhausted and divided their forces. The time has now come to bring the Russian advance to a standstill.

“For this reason, I have introduced measures of a most varied kind. It is now imperative, while holding firm in the Crimea [where the 17th Army had been isolated by the 4th Ukrainian Front], to hold or win back the following line:

“Dniester to northeast of Kishinev-Jassy-Targul Neamt—the Eastern exit from the Carpathians between Targul Neamt-Ternopol-Brody-Kovel.”

It was a tall order for the Germans and Romanians who had been so severely mauled by the Soviets only a few weeks before. Schörner’s command, which had been renamed Heeresgruppe Süd Ukraine on April 5, stretched from the Central Carpathian Mountains to the Black Sea in a line that was almost 300 miles long. His mixed bag of troops consisted of two Romanian armies (3rd and 4th) and two German armies (6th and 8th).

“Aktivnost”: Russian Subterfuge

Schörner was aware of the disparity in the armaments and fighting abilities of the German and Romanian troops under him, as was Hitler. In his April 2 order, Hitler said, “Romanian forces will be disposed in accordance with the terrain so that chiefly German troops occupy the sectors in danger of enemy tank attack.” He also ordered that German gun crews man the heavy antitank guns that were to be distributed to Romanian forces.

“Thank God for the mud,” was the phrase that passed the lips of generals and privates alike as they struggled to form a cohesive line. What the field commanders did not know was that Hitler had been partially right in his assessment of the Soviets’ offensive capabilities.

The problem was one of logistics. In a three-month period, Soviet forces had liberated most of the Ukraine, pushing the Germans back 250 to 300 miles in the process. Konev and the other commanders on the Southern sector had simply outrun their supply lines. There was also the matter of replacing the heavy troop losses that had been incurred during the offensive. This was partially overcome by simply drafting the male peasants in the liberated areas, but it would take time to turn them into soldiers.

With the onset of the muddy season, Stavka (the Soviet High Command) ordered all front commanders to go over to the defensive. This would have the twofold effect of allowing time to train replacements and supply depots to move closer to the front. Stavka was also using this time to build up forces for a new attack—one designed to crush the center of the German line on the Eastern Front—in a huge summer offensive.

To keep German intelligence off guard, Konev and the other front commanders in the South were ordered to keep their armored forces highly visible as part of a subterfuge that the Soviets called “aktivnost.” Basically, the activities of the tank armies and mechanized units, coupled with increased radio transmissions, were designed to fool the Germans into believing that those forces would remain adjacent to Schörner’s Heeresgruppe Süd Ukraine and Model’s Heeresgruppe Nord Ukraine (formerly Heeresgruppe Süd).

The plan also called for the Russian commanders to make a series of limited attacks with their armored forces, which would reinforce the German notion that new major offensives would take place in the south. One of those so-called limited attacks would take place around the Romanian town of Targul Frumos.

Ferdinand Schörner Reorganizes His Troops

While Konev waited for the ground to dry out enough to start his limited operations, the Germans used the respite to reorganize. Schörner was a tough, no-nonsense commander who was born in Munich in 1892. He had served with distinction in World War I, winning Germany’s highest decoration (the Pour le Mérite, popularly known as the “Blue Max”) on the Italian Front in 1917. During the same battle, another young officer by the name of Erwin Rommel also won the coveted award.

Schörner fought in the Freikorps in Upper Silesia after the war, rejoining the Wehrmacht in 1937. His promotions during the war resulted from his tactical abilities in tough situations. It also helped that he had Hitler’s confidence, being a loyal Nazi Party member from the early days of the movement.

Schörner tolerated no excuses from his commanders. His orders to General Maximilian de Angelis (6th Army) and General Otto Wöhler (8th Army) were simple and to the point: “The front will be held in accordance with the Führer’s wishes.”

Wöhler’s 8th Army occupied a pivotal area, guarding the Carpathian passes and providing a link with the 1st Panzer Army of Heeresgruppe Nord Ukraine. The 49-year-old Wöhler had served in staff positions during the war until he was given the command of the 1st Army Corps in 1943. He led the unit well on the northern sector of the Eastern Front, where his skill and initiative earned him the Knight’s Cross. On August 15, 1943, he was given command of the 8th Army and continued to lead it through the bloody retreat from the Ukraine to the Romanian border.

In mid-April, the general’s command consisted of an integrated force of German and Romanian units combined under the designation of Army Group Wöhler. On paper, the Army Group was 30 divisions strong, but 17 of those divisions were Romanian. The quality of the Romanian units ranged from good to poor, while the remaining German divisions were, in some cases, little more than battle groups. Wöhler’s main striking power lay in his panzer divisions, the 23rd, 24th, and 3rd SS “Totenkopf” (Death’s Head), and in the Panzergrenadier Division “Grossdeutschland” (Greater Germany or GD).

Faced with the task of defending a broad area against probable Soviet armored attacks, Wöhler used his mobile forces as “fire brigades,” keeping them on the few good roads in the area to counter any Soviet moves that threatened his line. The GD was no stranger to such actions.

Morale Was High Among the Grossdeutschland

Arguably the premier division of the German Army, the GD’s origins lay in the prewar Wachttruppe Berlin and elements of the Infanterie-Lehr-Regiment, which were formed into the Infanterie-Regiment-Grossdeutschland in 1939. Eventually becoming a Panzergrenadier division in April 1943, the GD differed from other German divisions in that its personnel came from all parts of the Greater German Reich rather than from a particular state or district.

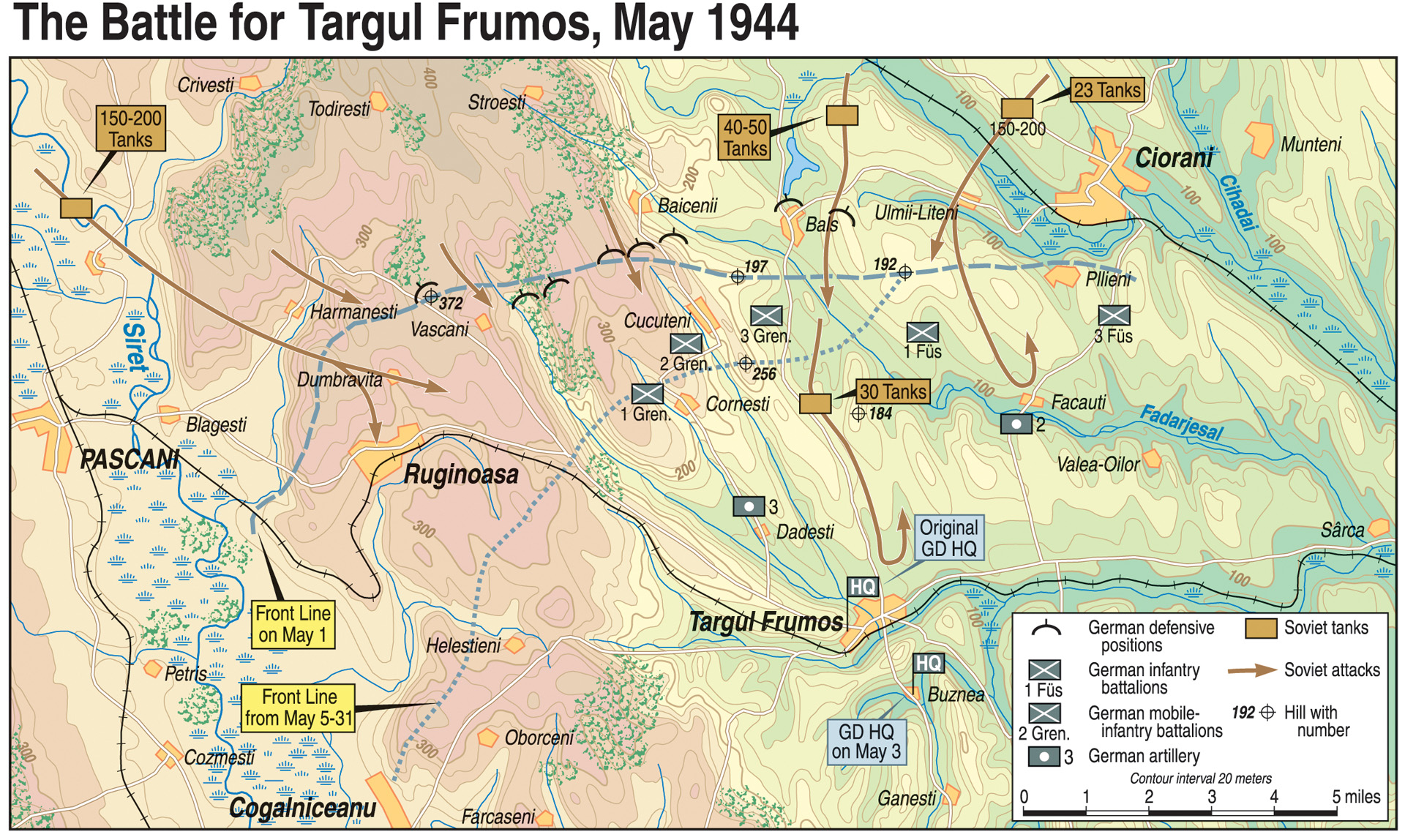

From January-March 1944, the GD had fought several battles around the Ukrainian city of Kirovograd before retreating west toward the Romanian border. Reaching the border at the end of March, it continued westward, thwarting a Soviet attack designed to cut the Jassy-Kishinev rail line during the first week of April, destroying 89 tanks and 10 antitank guns and inflicting heavy losses on Soviet infantry units. By mid-April, the division had taken up a defensive position that stretched from Ruginoasa, about 12 miles northwest of Targul Frumos, to the Siret River, about 12 miles northeast of the city.

Grossdeutschland was still a superbly equipped unit, and morale was still very high as the troops went about constructing their defenses. Each of the division’s two infantry regiments consisted of three battalions, each with four companies of 100 men, and one heavy weapons battalion per regiment. There was also a Sturmgeschütz (self-propelled assault gun) battalion with 35 to 40 weapons, a Pionier (Combat Engineer) battalion and an understrength Aufklärungs (reconnaissance) battalion.

The powerful armored fist of the division was made up of the four battalions of the Panzer Regiment GD. Each battalion had approximately 40 tanks. The Panzer Regiment GD had one battalion of medium Panzer IVs, two battalions of Panzer V “Panther” tanks, and one battalion of heavy Panzer VI “Tiger” tanks. The regiment’s massive firepower was backed up by an armored artillery regiment and three batteries of deadly, dual-purpose 88mm guns.

The Panzer Baron’s Division

Commanding this magnificent division was Lt. Gen. Hasso Eccard von Manteuffel, known throughout the Wehrmacht as the “Panzer Baron.” Von Manteuffel was small in stature, about 5 feet, 2 inches and 120 pounds, but he had gained the reputation of being one of the best panzer commanders in the German Army. Born in Potsdam in 1897, von Manteuffel had served in World War I and the postwar Reichswehr. General Heinz Guderian, the “father” of the panzer divisions, saw his potential as a tank commander before the outbreak of the war. Von Manteuffel honed his wartime skills, commanding a motorcycle battalion, motorized and Panzergrenadier regiments, and the famous 7th Panzer Division—Rommel’s old unit. He took command of GD on February 1, 1944, just as the battles raging around Kirovograd were in full swing.

Soviet forces facing GD had not been sitting idle while the spring rains fell. Along with training replacements and replenishing supplies, Konev launched a series of attacks designed to keep the Germans off balance. On April 16, Soviet forces launched a surprise attack on a GD company stationed in the town of Bals, about nine miles northwest of Targul Frumos. The Soviets succeeded in taking the town, but were soon driven back by a swift counterattack.

The continuing Soviet probing attacks convinced von Manteuffel that a major enemy effort would take place in the Targul Frumos sector. His scouting patrols reported a heavy Red Army buildup directly behind the front line, and further patrols confirmed that something was in the wind.

To forestall the inevitable, von Manteuffel ordered a limited attack of his own. On April 25, two Panzergrenadier battalions attacked Soviet positions near Hill 372. Supported by artillery and Sturmgeschütze, the Panzergrenadiers surged forward, driving the Russians from their positions and destroying several antitank guns and three tanks. Two days later, another German attack uncovered a very unpleasant surprise. Some of the knocked out Soviet armor was the new type JS III “Josef Stalin” tank armed with a powerful 122mm gun. The discovery served to hasten German efforts to construct the strongest defenses possible.

Von Manteuffel’s troops had laid out their defensive positions well. Although the Soviets occupied the high ground north of the Germans, most of the enemy-held hills that could be used for observation were about six miles away—too far to properly discern the German defenses. The wily panzer commander knew good tank ground when he saw it, and the terrain the Soviets would have to cross on their way to Targul Frumos was excellent for swift armored movement. However, the ground was also open for the most part, giving the Germans an excellent field of fire.

Preparing For the May Attack

GD’s Panzergrenadier and fusilier regiments would bear the brunt of the attack. Now that the ground had dried, Konev planned to send his tanks straight at the Germans, hoping to slice through the grenadiers and fusiliers and speed across the valley in a fast-moving assault. The German entrenchments were well fortified, covered by antitank guns and dug-in Sturmgeschütze. Hills 192 and 197, located west of the town of Polieni, gave the Germans excellent observation points from which to call in artillery fire on the Soviet avenues of approach. Hills 254 and 372 gave the Germans the same advantage to observe any Soviet forces attacking farther to the west. A second line of defense, also bristling with antitank weapons and infantry, was constructed about a mile behind the main line of resistance.

Most of the powerful Panzer Regiment GD was kept in reserve near Targul Frumos, ready to counterattack any Soviet forces that breached the German line. Von Manteuffel placed his headquarters on a hill behind Targul Frumos that had a perfect view of the entire sector. From this vantage point, the Panzer Baron and his staff would fight the battle with the skill of a maestro conducting a philharmonic orchestra.

The Germans expected the offensive against Targul Frumos to begin on May 1, the holiday of the proletariat. Air reconnaissance reported that tank and infantry concentrations were continuing to build up in front of the German lines, but the expected attack failed to materialize. Waiting is the worst part for any soldier, and the front-line troops nervously scanned the horizon until the sun set. Some breathed a sigh of relief as they lay in their trenches, trying to catch a few hours of sleep before the new day dawned. For others, the night was spent trying to control the tension that had built up during the day.

Dawn broke on May 2 at about 4 am. A few minutes after the first rays of light began to show, all hell broke loose as the Soviets unleashed a fierce artillery barrage. As the shells began striking the German positions, the infantry clawed deeper into the earth, hoping that death would pass them by. Some Germans were wounded, and their cries for help were heard despite the thunder of bursting shells; however, most of the entrenchments received little damage.

At around 5:20 am, the roar of tank engines signaled the start of the ground assault as armor from Bogdanov’s 2nd Tank Army, supported by infantry from General S.G. Trofimenko’s 27th Army, rumbled forward. The Panzergrenadiers gazed anxiously from their firing positions, waiting for the first shadowy appearance of the enemy through the smoke and dust that had been churned up by the bombardment.

Bogdanov’s plan of attack called for an armored assault of 200 to 250 tanks against Colonel Karl Lorenz’s Panzergrenadier Regiment GD. To keep the Germans off guard, other armored-infantry attacks hit the junctions of Lorenz’s regiment and Colonel Horst Niemack’s Fusilier Regiment GD, which was defending the German right.

T-34s Thunder Forward

The T-34 medium tanks and JS IIIs fired point blank at Lorenz’s Panzergrenadier positions as they thundered forward. Advancing through a valley between Ruginoasa and Hill 372, they hit the German line at full speed. The Germans fired with everything they had, but they were no match for the steel monsters racing toward them.

Most of the “old hands” had seen this repeated over and over again as Soviet materiel superiority increased in the East. When the Russian tanks were almost upon them, the men in the front-line positions crouched deeper into their foxholes, letting the Soviet armor roll over their positions. It took a brave man to let a 57-ton monster like the JS III run over his foxhole, and some of the Panzergrenadiers lost their nerve and broke. As they jumped up and ran, some were cut down by machine-gun fire, while others were crushed to death by the steel treads of the Russian tanks.

The 1st Battalion, Panzergrenadier Regiment, was particularly hard hit. As the Soviet tanks passed, the Panzergrenadiers struggled to get their firing positions back in order, but the Red Army infantry was already upon them. It was time to disengage, and several units were already moving back to secondary defensive positions. Many of them made it, but the 1st Company, commanded by Lieutenant Bernhagen, had waited too long.

“Move back, boys,” the lieutenant cried as wave after wave of Soviet infantry appeared out of the smoke. Many of the men, seeing that it was already too late, turned to face the Soviets. Most of them fired at the advancing enemy until they were cut down. Others raised their hands in a futile attempt at surrender, but to no avail. War on the Eastern Front had been a brutal affair since the early days of Operation Barbarossa, and prisoners were not at the top of either side’s priorities during battle. The surrendering men of the 1st Company soon joined their comrades, staring at the sky through unseeing eyes.

Keeping in constant contact with Lorenz’s command post, the battalion commander pulled the rest of his men back to the secondary line. Meanwhile, the Soviet tanks soon outpaced their infantry support. Infantrymen who had been riding on the backs of the tanks were swept off by machine-gun and rifle fire, and now the advancing armor was on its own.

An Initial Victory for German Forces

Suddenly, concealed German antitank guns opened fire. Tank after tank exploded as the murderous 75mm and 88mm shells struck home. The tanks continued to roll toward Targul Frumos, despite the casualties they were suffering. German Sturmgeschütze now joined the battle, also firing from concealed positions. The 1st Company, commanded by 1st Lt. Diddo Diddens, particularly distinguished itself against the advancing tanks, knocking out several of the lumbering giants as they made their desperate thrust toward their objective.

After running the gauntlet of antitank and assault-gun fire, 10 of the Russian T-34s ran straight into the assembly area of Colonel Willi Langkeit’s panzer regiment. Both sides were taken by surprise, but the German gunners reacted faster. Within a few seconds, the 10 tanks were blazing steel infernos. There were no German losses.

Seeing the plight of their comrades, several of the slower JS IIIs stopped and began firing at the panzers at distances of up to a mile and a half. Von Manteuffel happened to be at Langkeit’s headquarters when the shelling started. At first, both commanders thought that they had come under friendly fire, but they quickly realized that they were up against the new Soviet heavy tanks.

Von Manteuffel immediately sent word to Major Herbert Gomille’s 3rd (Tiger) Battalion, ordering a company of the heavy German tanks to engage the enemy. While the Tigers and JS IIIs fired at long range, a company of the faster, more maneuverable Panzer IVs used the limited cover in the area to advance to within 3,000 feet of the Soviets. As shells from their 75mm guns began to hit home, the remaining Soviet tanks retreated, leaving several burned-out hulls in their wake.

Approximately 250 Soviet tanks had been destroyed in the area between Targul Frumos and the front line of the Panzergrenadier Regiment GD for the loss of a mere handful of German tanks. It was an outstanding victory, but the battle was not over yet.

In Colonel Niemack’s sector, the Soviets were also in the midst of a combined attack. Niemack’s fusiliers, like the Panzergrenadiers on their left, let the Russian tanks roll over them before popping up to engage the accompanying infantry. The Soviet armor continued to advance without its infantry support and soon reached Niemack’s headquarters. Gathering his staff around him, Niemack ordered an attack at close quarters. With hollow charges, “sticky mines,” and bundles of grenades, the Germans knocked out tank after tank, destroying 24 of the enemy vehicles.

Standstill at Targul Frumos

A second Soviet attack at about 11 am succeeded in breaching the fusiliers’ line in several places, but once again the Soviet infantry was prevented from following its armor. Seeing the danger from the advancing Soviet tanks, Colonel Langkeit ordered most of the regiment to turn and attack the marauding Soviets. By noon, another 30 enemy armored vehicles lay burning on the Romanian countryside.

German bombers and Colonel Hans-Ulrich Rudel’s famous “tank busting” Ju-87 Stuka dive-bombers also joined in the carnage. Thoroughly disoriented, the few remaining mobile Soviet tanks fled, leaving the battlefield to the Germans. The bombers also hit several Soviet artillery positions, destroying guns that had pounded the Germans only a few hours earlier.

During the night of May 2, Langkeit moved some companies of Panthers and Tigers closer to the front line where they could directly support the entrenched infantry. Antitank guns were also redeployed so that the Soviet artillery could not immediately zero in on them the following day.

May 3 saw a renewed Soviet attack on both the Panzergrenadiers and the fusiliers. This time, as the Soviet tanks breached the infantry positions they were met with a hail of steel from the recently deployed Tigers, Panthers, and antitank weapons. German gunners fired round after round at the advancing Soviets, halting the attack and forcing the surviving tanks to once again beat a hasty retreat.

Try as they may, the tankers of the 2nd Tank Army and the infantry of the 35th Rifle Corps could not break through to Targul Frumos. Although they had pushed the German line back in some places, the toll taken by two days of continuous battle began to show.

It was the same for the Germans. As night fell on May 3, the exhausted infantry fell back into their foxholes, wondering how much longer they could hold out against the seemingly endless number of tanks and men that the Soviets were throwing against them. Some of the companies were down to platoon size, and although the Panzer Regiment had barely been touched, it was up to the worn out infantry to keep the line stable.

On May 4, the Soviets changed their tactics. Instead of advancing on a broad front, they concentrated their forces on a few select points. After blasting the breakthrough sectors with everything from mortars to rockets, they moved forward, hoping to obliterate everything in their path.

350 Tanks Destroyed, 200 Damaged

The fighting was particularly fierce around Hill 256, just southeast of Cucuteni, where Soviet and German infantry fought for control of an excellent observation point that commanded the entire sector. Hand grenades, flamethrowers, and razor-sharp entrenching tools were the weapons of the day as each side fought to eject the other from the strategic position.

In another sector, Captain Mayer, commanding the 2nd Battalion of the Panzergrenadier regiment, led a counterattack aimed at retaking the village of Giurgesti, which had fallen to the Soviets on May 2. In the hand to hand fighting that followed, Mayer was wounded, but his ad hoc assault group succeeded in driving the Soviets out of the village.

Except for the battle for Hill 256, the German line had been fairly well stabilized by the evening of May 4. A counterattack by Niemack’s fusiliers, supported by Panthers and assault guns, finally drove the Soviets off the hill on May 7. The Soviets had given their all, but the path to Targul Frumos and the Ploesti oil fields beyond had not been opened. For the next few months at least, the Red Army threat in Romania was over.

Von Manteuffel and his division had won a great defensive victory. During the first three days of battle, more than 350 Soviet tanks had been destroyed, with another 200 damaged. The GD lost a total of 10 tanks permanently destroyed. Although Soviet postwar accounts barely mention the battle, Targul Frumos was still being studied by NATO commanders well into the 1980s as a textbook example of how a combined arms defense could stop a massive Soviet attack. Perhaps the best reason for the German success was given by von Manteuffel years after the war: “In spite of the most careful preparations, the decisive factor in defense was the combat potential of the troops. It was this which allowed the defense to achieve the results it did—a huge fiasco for the Russians.”

An interesting story which provides good information and a fair bit of color commentary, giving not only the broad sweep of the action but also what the individual combatant might have experienced.

But of note, there were no JS III tanks in this action. None. None at all. Zero. They are mentioned many times, but they were not present. Russian sources are clear that this tank didn’t even enter production until a year after the actions described here, and saw no combat on the German/Soviet front during WW2.

A pity really, as it is hard for the historical enthusiast to read the article when this obvious error is repeated a dozen or more times in the narrative.

He means JS II tanks. Don’t be so anal, Mark.