By William H. Langenberg

In early September 1940, the world was in turmoil. The battle of Britain was nearing its climax, and elsewhere global tensions ran high. Election year strife was just beginning to augment the furor of clashes between isolationists and interventionists in the United States.

This world stage provided a fitting backdrop for the transmission of the following message to Congress by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on September 3: “I transmit herewith for the information of the Congress notes exchanged between the British Ambassador at Washington and the Secretary of State on September 2, 1940, under which this Government has acquired the right to lease naval and air bases in Newfoundland, and in the islands of Bermuda, the Bahamas, Jamaica, St. Lucia, Trinidad, and Antigua, and in British Guiana; also a copy of an opinion of the Attorney General dated August 27, 1940, regarding my authority to consummate this arrangement.

“The right to bases in Newfoundland and Bermuda are gifts—generously given and gladly received. The other bases mentioned have been acquired in exchange for fifty of our old destroyers.”

President Roosevelt’s Message Stirs Up Controversy

This unilateral action by the president created a heated controversy. Its legality and neutrality were openly questioned, and the sub rosa nature of the associated negotiations was severely criticized. However, as dramatic events in Europe and activities of a national election began to dominate newspaper space, the controversy gradually subsided.

President Roosevelt’s trade of 50 American destroyers for British air and naval bases has frequently been described in academic articles, popular periodicals, and books. Often the complex, secret negotiations leading to the exchange have been the principal focus of attention. The consummation of the trade via presidential executive agreement rather than congressional action remains controversial to this day. And the transfer of war materiel to a belligerent nation by a neutral country is still categorized by critics as an act of war.

From the time of the defeat of Poland in 1939 until April of the following year, the European conflict was in a state of relative inactivity. On April 9, 1940, however, this temporary stalemate ended. Germany launched a blitzkrieg attack on Norway and Denmark that astounded the world with its startling success. One month later, on May 10, the invasions of Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, and France began. On the day the Germans marched into the Low Countries, Neville Chamberlain resigned as Great Britain’s prime minister. He was succeeded by Winston Churchill, who immediately formed a new coalition cabinet and prepared to lead his nation through its gravest crisis.

Dutch Army Surrenders, Nazis Advance Westward

Meanwhile, the Nazi offensive made rapid advances. On May 14, the Dutch Army surrendered, and the German assault turned westward toward the classic battlefields of northern France. Armored columns broke through north of the Somme River to the English Channel. From there they proceeded northeastward to the Channel ports—within sight of Britain itself.

In just 11 days the Germans had accomplished what they had failed to do in four years of bitter fighting during World War I. This was a brilliantly executed military campaign, creating panic and demoralization among Allied forces. On May 28, King Leopold of Belgium surrendered. The French commander in chief, General Maxime Weygand, attempted to form a line of defense at the Somme, but this tactic was unsuccessful.

On June 4, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was evacuated from Dunkirk, and the Germans then turned south toward Paris. The French armed forces could not stem the Nazi onslaught. Paris fell on June 14, and three days later the French government sued for an armistice. Britain now stood alone in opposition to the Nazi enemy.

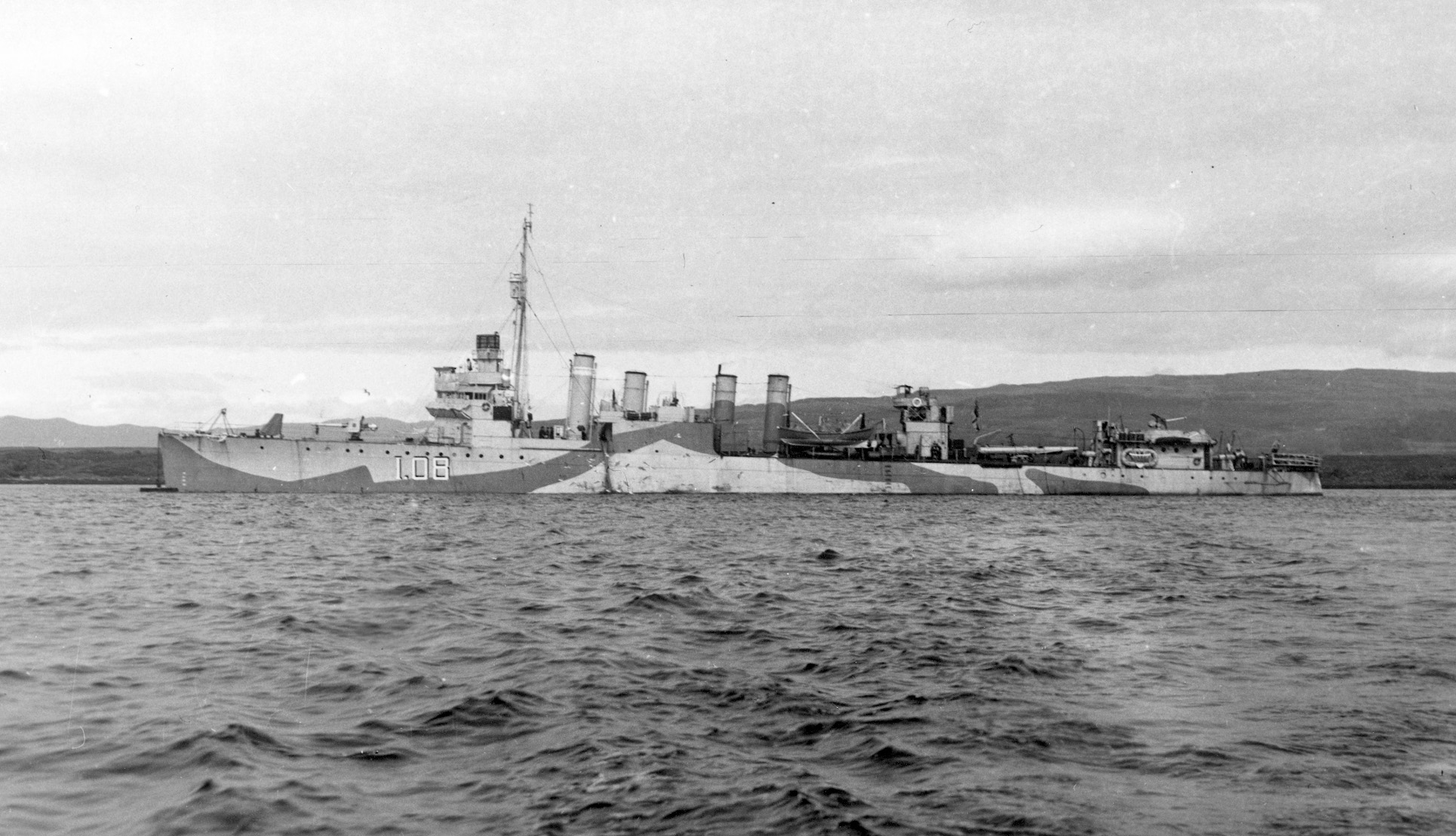

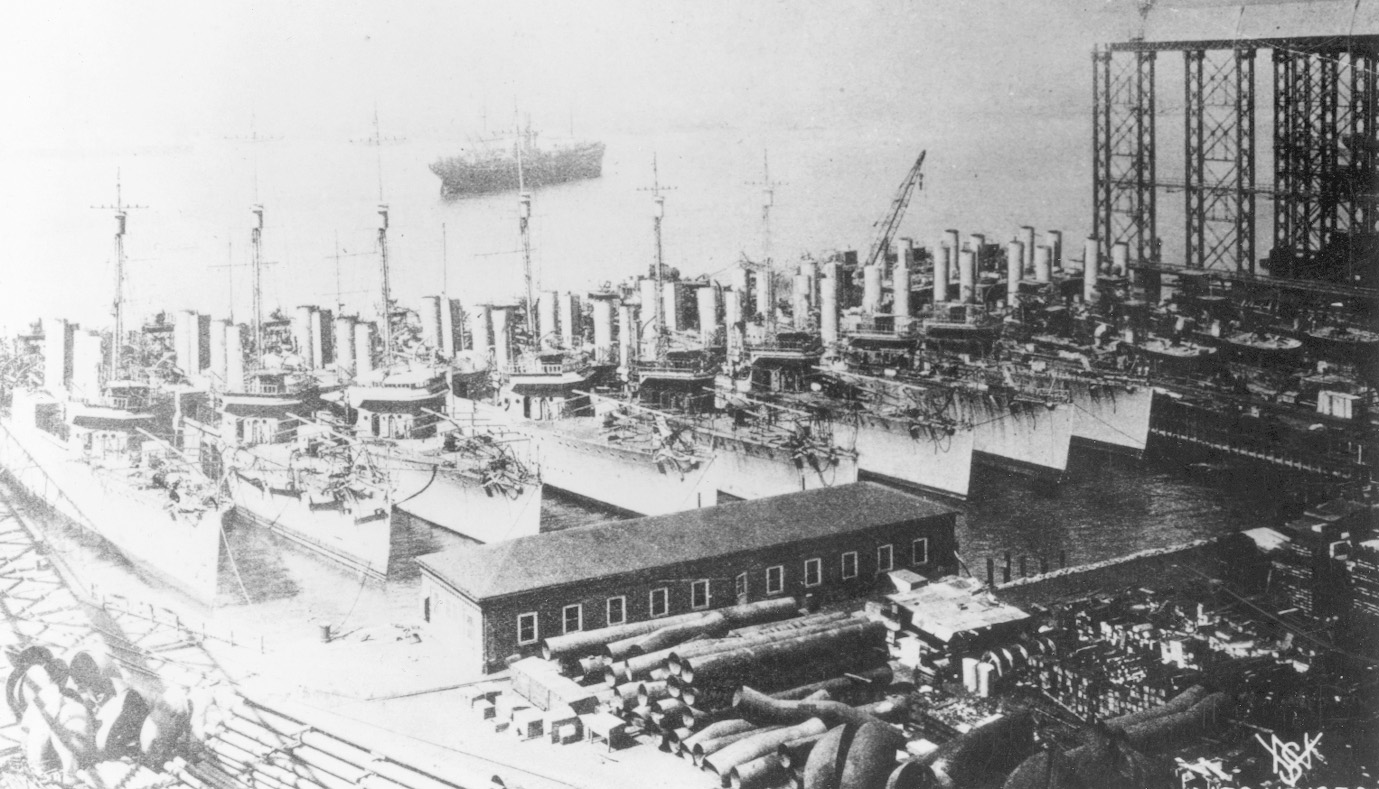

Given this historical background, how important were the 50 American destroyers to the British cause? The ships involved in the exchange were all Clemson-class destroyers built circa 1917-1922. Both the U.S. and the British Royal navies had begun preparations for their transfer in mid-August 1940. The destroyers were rehabilitated, provisioned, and sent to the transfer port at Halifax, Nova Scotia. Royal Navy crews to man the ships sailed for that port from England.

Exemplifying the alacrity of these proceedings, the first six ships to be transferred sailed for England manned by British crews on September 6, only three days after President Roosevelt announced the trade, and 40 of the 50 vessels arrived there before the end of 1940.

The transfer of the American destroyers came at a propitious time for Britain. Royal Navy destroyer losses had been severe during the Norwegian campaign and the subsequent evacuation of the BEF from Dunkirk, with scant chance of their replacements joining the Royal Navy until mid-1941. Even more serious, the Battle of Britain raged in full swing during September 1940, with the outcome still undecided.

Looming Threats for the British

Perhaps most ominous for Britain was the ongoing threat posed by the U-boat menace to Britain’s lifeline of transatlantic shipping. The possibility of an all-out German cross-channel invasion was also very real. These looming threats required constant destroyer patrols in the English Channel.

The 50 U.S. destroyers transferred to Britain were commissioned as Town-class destroyers in the Royal Navy. Forty-four were manned by Royal Navy crews, while six were crewed by the Royal Canadian Navy. All Royal Navy vessels initially steamed to Britain, where they were refitted to rectify defects, standardized with British equipment, and fitted with Royal Navy antisubmarine detection and weapons systems. This process required several months, thus the majority of Town-class ships did not become operational until early 1941. After refit, the Royal Navy destroyers were assigned to East coast escort duties, participation in the northern mine barrage, and North Atlantic convoy operations. Ships assigned to the Royal Canadian Navy principally engaged in convoy escort activities in the western Atlantic.

Most of the destroyers remained on frontline service until late 1943, when they were gradually replaced by more modern warships. As a group, the Town-class destroyers performed yeoman, sometimes spectacular, service. For example, between 1941 and 1943 Town-class ships participated in the sinking of 10 German U-boats and one Italian submarine while on patrol or as convoy escorts. One also unfortunately sank a Polish-manned Allied submarine that had wandered out of her assigned patrol area.

At least two specific actions by Town-class ships are worthy of special note. HMS Broadway, while serving on mid-Atlantic convoy-escort duties during May 1941, participated in one of the most important events of the war. On May 9, Broadway and other escorts of convoy OB318 depth-charged the German submarine U-110 to the surface, where the boat was abandoned by her crew.

Royal Navy Strips U-110 of Its Top-Secret Device

Royal Navy personnel boarded the crippled U-110, temporarily stemmed flooding that endangered its staying afloat, and removed intact the submarine’s top-secret Enigma machine, which was used to decipher coded messages. U-110 later sank while under tow toward Iceland, and the captured German crewmen were unaware that their boat had been boarded and stripped of its secret device.

Thus, the German High Command had no knowledge of this event, which aided efforts to decipher the Enigma code and led to the gathering of vital intelligence known to the Allies as Ultra. HMS Broadway received serious hull damage from one of U-110’s hydroplanes during this action, requiring two months of repairs in Britain. Thereafter, she continued convoy escort duties in the Atlantic with no further successes against submarines for nearly two years. On May 14, 1943, however, Broadway again achieved notoriety when she attacked and sank U-89. The destroyer remained active throughout the war.

The most highly publicized and dramatic action by a Town-class destroyer was the destruction of the Normandie Lock at the French port of St. Nazaire on March 29, 1942, via a nearly suicidal mission led by HMS Campbeltown. The former USS Buchanan, Campbeltown was refitted in England, then served as a convoy escort until being declared expendable in January 1942. She was prepared at the Devonport dockyard for the St. Nazaire raid. Modified to resemble a German torpedo boat, the destroyer was loaded with explosives and rammed into the Normandie Lock on March 29, 1942. Hours later, the ship blew up, rendering the lock inoperable in the process.

Not all of the 50 Town-class destroyers proved to be as effective as Broadway and Campbeltown. For example, HMS Cameron was being refitted in drydock at Portsmouth during December 1940 when she was blown off her blocks by a German bombing attack. Although the ship was subsequently salvaged, she was never recommissioned and was scrapped in December 1944. HMCS Columbia suffered an even more ignominious fate. After serving mostly as an convoy escort in Canadian waters, Columbia somehow steamed into a rock cliff at Moreton Bay in Newfoundland on February 25, 1944, crushing her bow. Towed to St. John’s, she lay as a bowless hulk until scrapped in August 1945.

“50 Ships That Saved the World”?

While some historians have asserted that these destroyers were “50 ships that saved the world,” that seems to be unwarranted hyperbole. The Town-class vessels as a whole were not refitted and ready for combat until early 1941. By that time, the Battle of Britain had been won and the German invasion threat toward England abandoned, while Hitler devoted his army’s attention to the invasion of the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, German U-boats continued to threaten crucial supplies reaching Britain by sea, and the Town-class vessels provided great service in antisubmarine operations throughout the war.

The 1940 trade of the 50 U.S. destroyers for six British naval and air bases also had lasting political effects. It set a new precedent for bold executive actions by U.S. presidents, and thus remains controversial to this day. And it pioneered the acquisition by a neutral country of property rights in a belligerent nation’s territory. In the long run, perhaps the latter two geopolitical issues should be perceived as even more important than the strategic and tactical impact of the 50 Town-class destroyers upon the outcome of World War II.

Most informative. Reading The Splendid and the Vile presently.Thank you.

Who crewed the 50 Destroyers on their Atlantic voyage from USA to Britain?

Ah… think I found my answer on second reading…

‘The 50 U.S. destroyers transferred to Britain were commissioned as Town-class destroyers in the Royal Navy. Forty-four were manned by Royal Navy crews, while six were crewed by the Royal Canadian Navy. All Royal Navy vessels initially steamed to Britain…’ M 😀