By David Luhrssen

After docking in New York on August 28, 1939, only four days before the outbreak of World War II, Captain Adolf Ahrens of Germany’s North German Lloyd shipping line was faced with a decision.

The independent-minded skipper could disobey orders again by allowing his ship, the passenger liner Bremen, the jewel of the German merchant fleet, to be interned by the neutral United States, or he could obey instructions and make a run for it, piloting the Bremen on a mad dash for home under the eyes and guns of Britain’s Royal Navy, whose surface fleet dominated the North Atlantic. Ahrens opted to pilot his ship to its berth in Germany.

[text_ad]

It proved to be the longest journey the Bremen had ever undertaken. After a dangerous three-month odyssey, the luxury liner finally returned to her mooring at Bremerhaven’s Columbus Quay. Ahrens relied on skillful seamanship, good fortune, and the assistance of Nazi Germany’s ally at the war’s onset, the Soviet Union.

The S.S. Bremen: Designed by a Award-Winning Architect

The Bremen was among the most highly pedigreed blockade runners in maritime history. Along with her sister ship, Europa, the Bremen represented North German Lloyd’s bid to challenge the Cunard Line and the French Line for luxury transatlantic passenger service in the years between the world wars. Architect Bruno Paul, whose work won prizes for Germany at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair and whose buildings were noted for their clean, classic elegance, led her design team. Paul, who had blueprinted one of Berlin’s first high-rise buildings, gave the Bremen’s salons and cabins a thoroughly modern appearance. Among his innovations was a unique split-funnel design in which both of the ship’s twin stacks, obstructions on most passenger vessels, parted on the promenade deck to provide additional space for salons and entertainment rooms.

The Bremen was built for speed as well as comfort, taking the coveted Blue Riband for fastest Atlantic crossing on her maiden voyage in July 1929. Cruising at 27.83 knots, she beat the Cunard liner and previous Riband holder RMS Mauretania by two knots, traveling from Cherbourg to New York in only four days, 18 hours, and 17 minutes. The Bremen was nearly as fast as light cruisers, the greyhounds of the world’s navies. It was as up-to-date as possible and was equipped with desalination machinery, transforming seawater into drinking water.

The German liner appeared on the seas only months before the Wall Street stock market crash of October 1929, which caused a global depression and created circumstances favorable for the rise of Adolf Hitler. Labor unrest, including the periodic shipyard strikes that delayed the Bremen’s construction in the old commercial city whose name she bore, would never slow the ship in the years following Hitler’s appointment as German chancellor in 1933. The Bremen’s crew of over 900 men and a few women included a Nazi Party cell and even a unit of the SA, the brown-shirted storm troopers who helped Hitler bully his way to power, but the passengers who traveled on the Bremen after 1933 were seldom disturbed by politics.

In a bid to retain foreign clients and to polish Germany’s image as a modern, moderate state, it was the expressed policy of German shipping lines to downplay Nazism. Except for the swastika flag fluttering from the stern, the Nazi takeover brought few changes to the Bremen from the passenger’s perspective.

The mood was decidedly less than carefree, however, when the Bremen sailed from Bremerhaven on August 22, 1939, with cargo, thousands of mailbags, and 1,200 passengers onboard, most of them U.S. nationals trying to outrun the storm clouds gathering over Europe. On the following day the liner anchored briefly as scheduled in the ports of nations that would soon be at war with Germany, taking on an additional 500 passengers at Southampton and Cherbourg before making for the open Atlantic.

Arriving in America Against Orders

On the evening of August 25 at 56 degrees longitude, the Bremen received word from Germany that all German ships on the high seas were to return to home port before the outbreak of war. Captain Ahrens ignored the order and continued sailing for New York.

Likewise, on the following day he again broke the rules by radioing Germany of his intention to proceed to New York. On August 27, Ahrens broke radio silence again by informing his superiors that he had only enough fuel left for three days and would sail to Havana, where passengers would disembark. This time the German Admiralty and Transportation Ministry issued him clear and direct orders to disembark his passengers in New York, refuel, and return to Germany as soon as possible. Ahrens finally obeyed.

After the Bremen arrived in New York on August 28, greeted by reporters and newsreel cameras along with tugboats and customs officers, Ahrens quickly and ingeniously prepared the ship for what promised to be her roughest journey by purchasing black paper from a theatrical supply company to black out the hundreds of portholes and windows. Although North German Lloyd’s New York bureau passed on instructions from the home office for the liner’s swift departure for Bremerhaven, U.S. Customs officials were not eager for the Bremen to leave. Working under the authority of recently enacted neutrality regulations, 26 customs agents boarded the liner on the morning of August 29, searching her from stem to stern for weapons and contraband, inspecting the lifeboats, counting the lifejackets, and taking breaks for coffee and meals. At the end of the workday the customs agents departed, explaining that their report had to be read by the chief of customs in New York before the ship could leave.

Because of the unexpected delay, Ahrens granted his crew a furlough for the night. Many of the sailors had been so familiar with New York from previous trips that they jokingly referred to the city as “a suburb of Bremerhaven.” As they sauntered through Times Square, they found a message about their ship’s arrival running on the electrically lit billboard of the New York Times building. Some of the sailors repaired to the German restaurants of Manhattan, while others took in such sights as Broadway and Rockefeller Center.

The Bremen’s officers believed that the Roosevelt administration delayed their departure in order to give the Royal Navy time to establish pickets in the Atlantic or in the hope that Ahrens would lose heart and allow his ship to be interned and, perhaps, eventually seized by the U.S. Merchant Marine.

On the morning of August 30, customs agents boarded the liner again, this time removing paneled walls, searching the tanks in the engine room, and probing the deepest recesses of the ship. They returned the following morning, checking the ship’s pumps and, according to an account later published in Germany, milling around and dragging their feet. The crew could only take comfort from observing that customs agents were also inspecting the French liner Normandie docked nearby.

The Crew Prepares For War

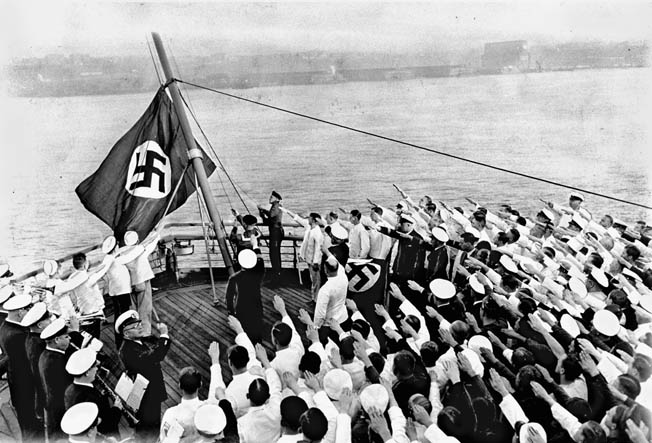

Late that afternoon, U.S. authorities, finding nothing, finally authorized the Bremen to depart. At 6:30 pm, she finally set sail. Slowly gliding past lower Manhattan on her way to the Atlantic, the ship’s band struck up “Deutschland Uber Alles” and the Nazi Party anthem, “Horst Wessel Lied.” Many of the crew members had assembled on deck, their arms raised in the Nazi salute. But political zeal and martial fervor did not cancel out the ancient courtesies of the sea. When the Bremen passed the Normandie, sailors from both ships waved and dipped their colors in salute. Unlike the Bremen, the Normandie would never leave New York harbor. It was interned and eventually requisitioned by the United States as a troopship before being destroyed at dockside by a mysterious fire in 1942.

After passing the lightship Ambrose, the Bremen’s crew, working from lifeboats suspended above the waterline, rapidly painted the liner’s black hull a dull gray to match the overcast North Atlantic. The Bremen’s white superstructure and yellow funnel were also painted in a mixture of white and black paint once the gray ran out. The ship’s name and home port were also covered in dark paint. Speeding at 27-28 knots, the Bremen continued northeastward through heavy seas and thick fog. Running lights were extinguished, radio silence was maintained, and extra lookouts were posted on deck and on the masts. At the first indication of another ship on the horizon, the Bremen changed course to avoid being spotted.

While hoping either for peace or to outrun the start of war, the officers drew up detailed plans for scuttling the ship and evacuating the crew in the event of being captured by the British. Mattresses, wood, and gasoline were piled in key places in order to set the ship ablaze, even as the engineers planned to open ducts to flood the liner’s lower decks. Sandbags were positioned around the wheelhouse in case British aircraft strafed the ship.

Hunted by the Royal Navy

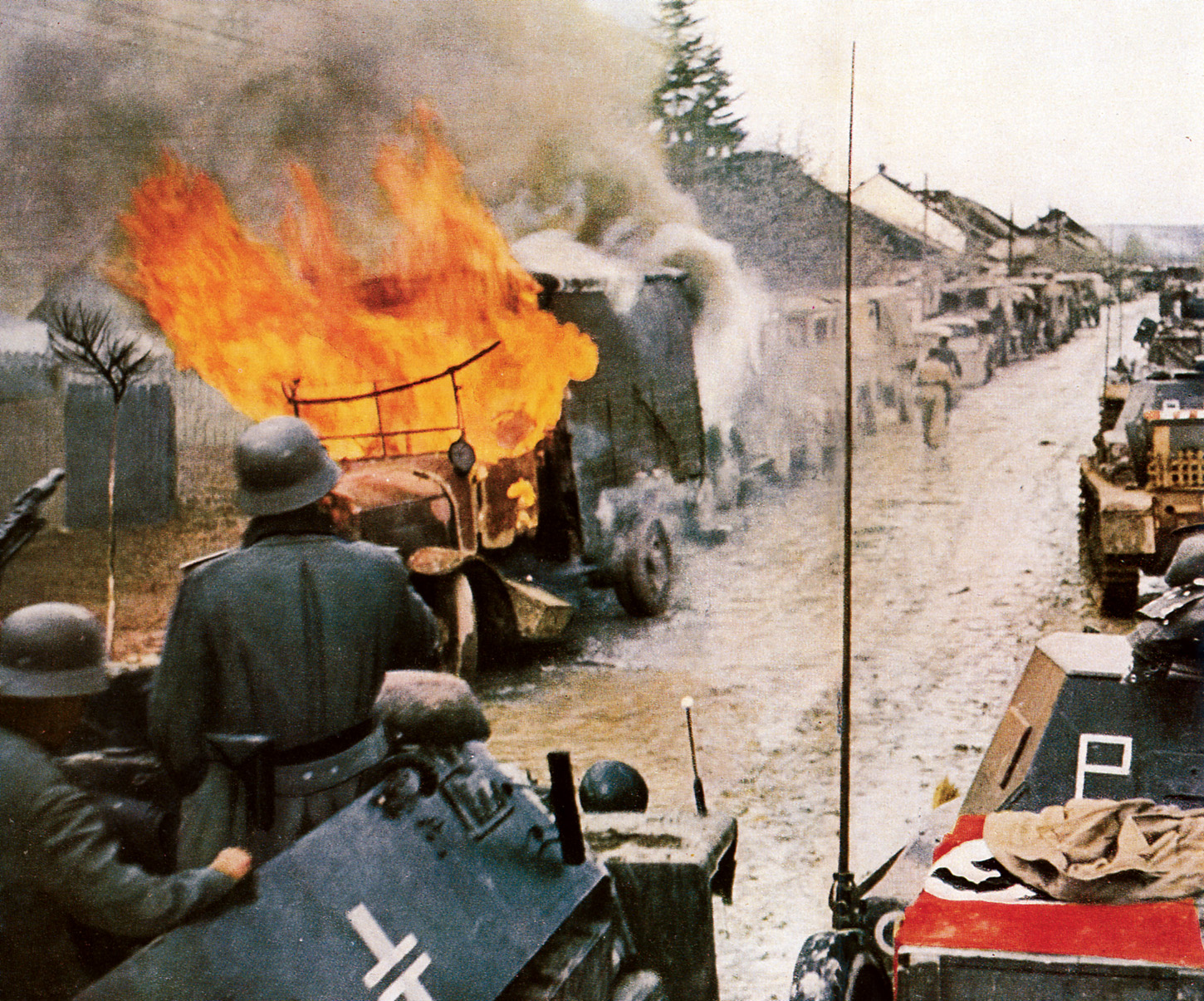

On September 1, tension thickened when the wireless received word that the German Army had rolled across the Polish border. The Germans had hoped that France and Great Britain would stay out of Hitler’s way, as they had so many times before in recent years. News updates were regularly posted on the ship’s bulletin boards. By September 3, when Britain declared war against Germany, the Bremen was south of Iceland and entering the Denmark Strait. The captain assembled the crew in the main dining hall to relay the disheartening news.

By that time the Bremen was being hunted by considerable units of the Royal Navy, anxious to seize or sink the pride of Germany’s merchant fleet. British submarines lurked near the entrances of Germany’s ports. Two British cruisers accompanied by eight destroyers prowled the coast of Norway, and heavier units of Britain’s Home Fleet patrolled the North Atlantic. But the British never expected the Bremen to brave the threat of icebergs by crossing the Arctic Circle into the chilly Denmark Strait. Lacking clothing warm enough for the cold, the crew availed themselves of clothes that would normally be on sale for passengers in the ship’s store, piling on layers to retain body heat.

Arriving Safely in Murmansk

On September 6, Germany’s ambassador in Moscow, Count Friedrich Werner von der Schulenberg, informed the Kremlin of his government’s intention to divert blockade runners to the ice-free northern Russian port of Murmansk on the eastern shore of the Kola Inlet, 30 miles from the Barents Sea. Soviet authorities were expected to unload German ships and send their cargo by rail to Leningrad, where German freighters waited. The Soviets complied willingly.

Ahrens received orders to steam for Murmansk while in the Denmark Strait. Given the confusion of war, the crew of the Bremen entered Russian waters in a state of anxiety. The Germans reversed direction and withdrew to sea at the sight of a plume of smoke from low in the waterline, steaming toward them from the shore. They easily outran the warship, which turned out to be a Soviet torpedo boat. After it was identified as friend and not foe, the Bremen resumed course and rendezvoused with the Soviet warship. A boarding party was dispatched from the torpedo boat. The German and Soviet officers tried to communicate in halting English but were relieved to discover that one of the Bremen’s stewards, born in Kronstadt before World War I, was fluent in Russian.

On September 6, the Bremen finally dropped anchor, having covered 4,045 nautical miles since leaving New York six days and 13 hours earlier. Lining up on both sides of the deck for a view, the crew saw a port city that was raw, unfinished, and largely unpaved. Among the few modern amenities offered by Murmansk were the Hotel Arctic and a clubhouse for foreign sailors, mainly Swedish, Dutch, and Norwegian merchant seamen.

During the Bremen’s sojourn in Murmansk, the liner’s whereabouts were the subject of avid speculation in the foreign press. An Italian newspaper put the Bremen at Veracruz while a Stockholm paper claimed the liner had been reflagged under Italian colors and was making her way to Italy. In Antwerp reporters speculated that the Bremen had arrived in Reykjavik, Iceland. One Belgian paper guessed the truth, calling Murmansk the ship’s destination.

On September 18, about 850 crew members were sent home to Germany aboard a pair of Russian trains, leaving behind a skeleton detail of 70 officers and men to stand watch and maintain the ship. Winter came early in that part of the world. It was already snowing when the trains pulled out of Murmansk.

A Hero’s Welcome

Boredom set in during the months when the Bremen waited for the last leg of its journey home. By the end of September a German tanker arrived in Murmansk to replenish the Bremen’s fuel. The outbreak of the Winter War between the Soviet Union and Finland after Stalin invaded the neutral country on November 30 dampened spirits. After a Finnish air raid damaged a nearby air base, the Soviets insisted that all ships in the harbor darken their lights.

Murmansk was busy with German shipping during this time. Also in port was the U.S. merchantman City of Flint, which had been seized by the pocket battleship Deutschland in the North Atlantic for carrying contraband bound for Britain. Ironically, Murmansk would become a key destination for Anglo-American convoys supplying the Soviets after Hitler turned on Stalin in 1941. Ahrens bided his time, waiting patiently for the snow squalls of winter before taking the Bremen back to sea and to Bremerhaven. Fifty-seven of his crew secretly returned to the Bremen in preparation for the journey home.

Early morning on December 7, the ocean liner pulled out of Murmansk before sunrise and under cover of a heavy snowstorm. She was a gray ghost sailing against a dark horizon; the long nights and rough seas at those latitudes in the last weeks of the year aided the voyage. However, the Bremen had one close call with the Royal Navy after leaving the safe haven of Murmansk. On December 12, the British submarine Salmon intercepted the Bremen off the Norwegian coast. The Salmon was enjoying an eventful patrol in the North Sea, which included the unusual feat of torpedoing an enemy submarine, the U-36.

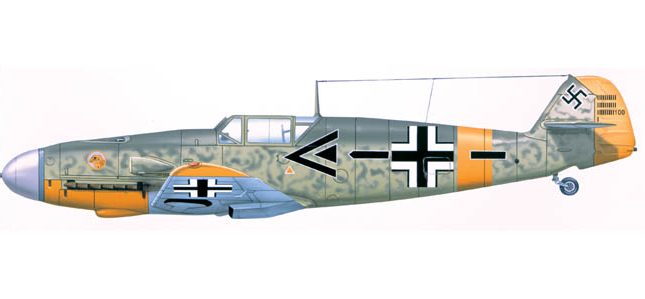

The Salmon’s skipper, Lt. Cmdr. E.O. Bickford, surfaced after identifying the Bremen through his periscope and gave the liner repeated warnings to surrender. Bickford was unable to claim his prize. He was forced to crash-dive when a Dornier Do-18 flying boat, dispatched by the German Navy to escort the Bremen, appeared on the horizon. The Salmon survived to cripple the German cruisers Leipzig and Nuremberg before returning to base.

On December 13, the Bremen finally returned to its berth in Bremerhaven’s Columbus Quay. “The joy at having won the race twice, and having brought safely home our beloved Bremen, this precious possession of the German mercantile fleet, can be seen in everyone’s eyes,” Ahrens said.

The captain and crew received a hero’s welcome from the chairman of North German Lloyd and the Reichsminister of Transportation. A band played, and a company of naval sailors presented arms. Ahrens’s earlier disobedience on the high seas before the outbreak of war was forgotten. He was promoted to commodore for his derring-do and seamanship. He was lionized in the German news media and received thousands of letters from well wishers. The Bremen won its battle, but would never go to sea again.

Sinking the Bremen

In the following months, the ship was painted in camouflage colors and refitted as troopship No. 802 for Operation Sea Lion, the German invasion of Great Britain that would never be launched. Aware of the Bremen’s new mission, the Royal Air Force attempted but failed to sink her. On March 16, 1941, a fire broke out in her expensively furnished woodpaneled dining room, which had been converted to a mattress storeroom. It spread over the entire ship, and despite a vigorous response from Bremerhaven’s fire brigades burned out of control. Badly listing toward the quay, the Bremen was flooded so that she could right herself and sink in the shallow water of the Weser River, making salvage of machinery easier.

The Gestapo initially suspected that British intelligence had a hand in the destruction of the ship, but before long the investigation fell upon a 15-year-old deckhand from the Bremen, Walter Schmidt, who eventually confessed to having set the fire in revenge for a clip on the ear given him by a supervisor. Wartime justice was swift and severe. Schmidt was executed.

The Bremen, which began the war with a storybook adventure, ended it as charred hulk brooding over the ruins of Bremerhaven, a port city regularly visited by the RAF and U.S. Eighth Air Force bombers. In 1946, the Bremen was towed to a sandbar three miles up river. The mammoth ship, resembling by then a beached and decomposing whale, was gradually dismantled and scrapped between 1952 and 1956.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments