By Flint Whitlock

It was unbelievably dull and uncomfortable duty, often interspersed with moments of sheer terror and the possibility of sudden and violent death. This was the Murmansk Run, the convoy duty on the North Atlantic.

Thousands of cargo ships, manned by tens of thousands of brave British, Canadian, and American civilian merchant mariners, along with Navy and Coast Guard personnel, made the hazardous voyages carrying invaluable supplies to America’s chief Allies—Great Britain and the Soviet Union—months before, and years after, the United States was propelled into the war on December 7, 1941.

The voyages across the North Atlantic and from Iceland to the Russian ports of Murmansk, Archangel, and Kola Inlet involved more hazards than in any other kind of naval duty. Severe weather was commonplace. Ice fields could be encountered at any time of year. Floating mines were a constant menace. German submarines, surface craft, and warplanes could strike at will from nearby bases in German-occupied Norway. And, prior to the spring of 1943, when an effective Allied antisubmarine offensive got underway, ships and men making the so-called “Murmansk Run” had about one chance in three of returning.

This was no glamorous sea campaign, with full-sail, tall-masted men-of-war firing broadside after broadside into their enemy’s rigging. It was a cold, dirty, dangerous business in which seamen might be blown into a flaming sea of burning oil and left to die of wounds, burns, or hypothermia.

Once the convoys reached their destinations, there was no guarantee of safe harbor, either, for the Germans often attacked while the cargo ships were in port, unloading. Then there was the return trip.

The history of the convoy operations, which went on nearly continuously from the autumn of 1939 until May 1945, is one of intense suffering, great loss, unparalleled bravery, and uncompromising devotion to duty. The epic saga is one of the most remarkable chapters of World War II—one that has for too long been overshadowed by other events.

The necessity of making the treacherous convoy runs began just days after Britain and France declared war on Germany following the Third Reich’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. At that time, Admiral Karl Dönitz, chief of Germany’s submarine force, instituted a program designed to starve Britain into submission by cutting her shipping routes to North America with his U-boats. At the start of the war, Germany had 46 U-boats; by the end, she would have 863 in commission.

Canada, which had become an independent democratic monarchy in 1931, firmly aligned herself with Britain when the Ottawa Parliament declared war on Germany on September 10, 1939. With only a tiny navy, Canada began a crash building program of warships and merchant vessels, and the Royal Canadian Navy soon found itself escorting ships carrying war goods across the North Atlantic to Britain.

The purpose of the convoys was to keep a lifeline of desperately needed war matériel flowing to Great Britain and, later, the Soviet Union. Great Britain was not self-sustaining. As her planes were downed, her ships sunk, her armies decimated, and her stocks of food, weapons, and ammunition depleted, Britain turned to her colonies and former colonies, especially Canada, for help.

Clustering freighters into convoys, as was done during World War I, helped somewhat to fight off the unseen enemy, but then Dönitz countered by grouping his submarines into wolf packs of three or more boats that overcame the transports’ defenses. In 1940 alone, U-boats accounted for the sinking of 375 ships in the North Atlantic. In 1939, Britain’s imports totaled 55 million tons; in 1941, the total was down to 30 million. Britain was losing three times as many ships as her shipyards could build and was on her way to losing the war unless something drastic was done—and quickly.

With the United States lay Britain’s last, best hope, but sentiment in America was decidedly antiwar. The U.S. was also still feeling the effects of the Great Depression, which had begun in October 1929. During the Depression years of the 1930s, America’s fleet of merchant ships had fallen into disrepair. Crews were laid off. Fractious martime unions were battling with each other and with the ship owners.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had once been assistant secretary of the Navy, was obsessed about the country being prepared in the event the U.S. was drawn into another war.

Fortunately, on June 29, 1936, Congress had the foresight to pass the Merchant Marine Act, which created the U.S. Maritime Commission to “further the development and maintenance of an adequate and well-balanced American merchant marine, to promote the commerce of the United States, and to aid in the national defense.”

Merchant seamen in 1936, however, were in short supply. Before the outbreak of World War II, only 55,000 experienced Merchant Mariners were working for American shipping companies. If the United States became embroiled in the conflict, Roosevelt knew many thousands more would be needed.

Specialized cargo ships—hundreds or thousands of them—would also be required. But from where would they come? Many of America’s shipyards and steel mills had shut down during the Depression, and skilled shipfitters were a vanishing breed. Before World War II, fewer than 100,000 persons were in the national shipyard labor force.

The U.S. Navy was Comprised Then of Only 23 Ships While the Privateers Possessed 517

The U.S. Maritime Commission’s long-range plans were to build 50 ships annually for 10 years, but in 1939 as war clouds darkened Roosevelt doubled this goal to 100 per year. Still, this number would prove woefully insufficient.

The United States Merchant Marine has a proud history that goes back to the very founding of the republic. When the original 13 colonies declared their independence from Great Britain, the Continental Navy had only 31 ships. The Navy issued “Letters of Marque” to armed, privately owned merchant vessels and commissions for privateers, which were outfitted as warships to attack Britain’s merchant ships. A total of nearly 1,700 privateers, manned by merchant seamen, would see duty in the War of Independence. Hundreds of merchant ships also plied the waters of the East Coast, delivering supplies, armaments, and troops where needed.

During the next national conflict, the War of 1812, which began when the British Navy kidnapped American merchant sailors and pressed them into service aboard the king’s ships, merchant mariners also played significant roles. The U.S. Navy was comprised then of only 23 ships, the privateers 517. In terms of shipboard guns, the Navy possessed 556, the privateers nearly 2,900.

And so it was through the years. During every conflict that required the use of ships, the Merchant Marine was there, risking lives, suffering casualties, transporting men and matériel, and accomplishing the assigned mission despite its quasi-military status.

With the gathering storm in the late 1930s, men to man the merchant ships were not the only thing needed. An all-out program to build a fleet of cargo ships, “a bridge of ships” as Roosevelt called it, was clearly required. In August 1940, the president increased the U.S. Maritime Commission’s quota of new ships to 200 annually. But what kind of ship design would work best, and who would build them? America’s still-operating shipyards had plenty of U.S. Navy contracts for all manner of warships to keep them busy. There simply was no extra manufacturing capacity available to build the necessary cargo ships.

Necessity is often the mother of invention, and so, in September 1940, a British Merchant Shipbuilding Mission team came to the United States hoping to fill an order for 60 new freighters. The plans they carried were of an “Ocean-class” freighter whose design was virtually unchanged over the past half century. Big and bulky, with plenty of cargo-carrying capacity, it had a simple, 135-ton, coal-burning, reciprocating steam engine—antiquated but reliable.

Unfortunately for the British, American shipyards, awash in orders for warships, were not about to halt construction of destroyers and cruisers to build the dumpy, old-fashioned freighters. Besides, due to the high construction costs and a surplus of old freighters, America’s shipyards had built only two ocean-going, dry cargo ships between 1922 and 1937. Basic knowledge was lacking.

Navy Vice Admiral Emory S. Land, chairman of the Maritime Commission, initially agreed to assist the British delegation in finding a builder, but he did not like their design of the proposed cargo ship. He disassociated the U.S. Maritime Commission from the project but made arrangements for the British to deal directly with private shipyards.

Soon the British paired up with Todd Shipyards, a New York ship repair company. Todd Shipyards put together a consortium of six companies headed by a builder named Henry J. Kaiser—a man with plenty of gusto but no experience in mass-producing ships (his companies and partners did, however, have experience in building such projects as the Grand Coulee Dam, the piers for the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, and a third set of locks for the Panama Canal. Kaiser formed a company named Todd-California Shipbuilding and established two new yards, one at Richmond, California, on San Francisco Bay, and another in South Portland, Maine, in partnership with the Bath Iron Works. In December 1940, the building of the facilities that would build the ships commenced.

On January 3, 1941, President Roosevelt announced a $350 million shipbuilding program, and Land changed his opinion of the British design when he realized that the Germans were sinking British cargo ships faster than the losses could be replaced. He decided to adopt the British design for American cargo ships and officially designated it the “EC2”—E for Emergency, C for Cargo, 2 for large capacity. An oil-burning engine was substituted for the coal-burning one.

After Land showed the president the plans, Roosevelt laughed and said, “Admiral, I think this ship will do us very well. She’ll carry a good load. She isn’t much to look at, though, is she? A real ugly duckling.”

In early 1941, the U.S. Maritime Commission put in an order for 260 cargomen. Land called the yet-to-be-built armada of cargo vessels the “Liberty Fleet,” and the name, “Liberty ship,” rather than “ugly duckling,” caught on. The first Liberty ship, the SS Patrick Henry, was launched on September 27, 1941. In just three years, the U.S. would build the equivalent of more than half of the world’s prewar merchant shipping while, during the same time period, turning out the greatest armada of fighting ships in history.

The order was placed not a moment too soon, for the war was coming ever closer to the United States. On November 17, 1941, Congress authorized the use of Navy guns and gunners on American merchant ships. Less than a month later, the United States was at war.

Then, on February 7, 1942, Roosevelt signed Executive Order No. 9054, establishing the War Shipping Administration (WSA). This order, according to the language, assured “the most effective utilization of shipping of the United States for the successful prosecution of the war.” The role of the WSA was to purchase and operate the civilian shipping needed to supply America and its Allies around the globe with men and materiél.

Such a program was badly needed, for the lessons of the Great War were still uppermost in the minds of Roosevelt, Land, and Admiral Russell R. Waesche, Commandant of the Coast Guard. Germany’s U-boats and surface raiders had decimated the merchant vessels that had carried war goods across the Atlantic. To preclude this from happening again, the U.S. put all American cargo ship companies, such as the Isthmian Lines, under government contract and speeded up the Liberty ship program. While the experienced shipyards concentrated on constructing the complex and sophisticated warships, newly organized shipyards popped up and began quickly putting together, from sets of standardized plans, a huge fleet of Liberty ships.

Liberties were built in 18 emergency shipyards along the Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf Coasts, including the Kaiser shipyards in Richmond, California; the J.A. Jones Construction Co. in Brunswick, Georgia; Todd-Houston Shipbuilding in Houston, Texas; and New England Shipbuilding Company in Portland, Maine.

The Liberty ships soon became the workhorses of the Merchant Marine fleet, but, like anything rushed into production, they left much to be desired. Liberty ships were big and slow and not always built to ensure maximum seaworthiness, especially when subjected to enemy bombs and torpedoes. Nor were the “square-hulled” vessels graceful, as ships often are. The freighters were not designed for looks or luxury but for utility.

As unskilled shipbuilders became more and more skilled and mass-production techniques of prefabrication and preassembly became more standardized, the average length of time to build a Liberty ship dropped from 108 days in 1942 to less than 50 days in 1943. Most of the 250,000 pieces that made up a Liberty ship were prefabricated, preshaped, and preassembled into approximately one hundred sections that could be assembled on the shipyard ways.

A Single Liberty Ship Could Carry 2,840 Jeeps, or 440 Light Tanks, or 230 Million Rounds of Rifle Ammunition, or 3,440,000 C-rations.

Liberty ships were relatively fast and easy for an unskilled crew to build. A Liberty ship required 3,425 tons of hull steel, 2,727 tons of plate, and 700 tons of shapes, which included 50,000 castings. Sixty-one percent of the Liberty ship was prefabricated. Rather than being built with the slow, traditional rivet method, Liberty ships were mostly welded together—a process that saved time but sacrificed strength. Average time to construct one Liberty ship was about two months, although the record for the fastest Liberty ship built was set by the Kaiser shipyard in Richmond. From keel laying to launching, the SS Robert E. Peary was finished in 4 days, 15 hours, and 30 minutes and sailed three days later. The ships cost approximately $2 million per copy.

Cargo capacity of a single Liberty ship was equal to that of 300 railroad freight cars. One Liberty ship could carry 2,840 jeeps, or 440 light tanks, or 230 million rounds of rifle ammunition, or 3,440,000 C-rations. With a length of 441.5 feet and a beam, or width, of almost 57 feet, the Liberty ships had five holds and could haul 10,900 deadweight tons (the weight of cargo) or 9,140 net tons (the amount of space available for cargo, fuel, passengers, and crew. Each ship had built-in booms and cranes to load and unload cargo. Propulsion was provided by two oil-fired boilers and a triple expansion steam engine that generated 2,500 horsepower. Cruising speed was 11 knots (approximately 12-13 miles per hour).

Each ship typically had a crew of 41 racially mixed civilian merchant sailors and a complement of Navy personnel known as the Armed Guard responsible for operating the guns and communications equipment. Weaponry consisted of two 3-inch naval guns and eight 20mm cannon. The 3-inchers, placed at the bow and stern of the ship, could be used against U-boat or aircraft attacks, while the 20mm guns were located in shielded tubs along the sides of the ship. Barrels with chemicals to provide smoke screens were located at the ship’s stern.

By war’s end, more than 2,700 Liberty ships would be produced. But the war would not wait for them.

To man the ships once they slid down the ways, Vice Admiral Land and Admiral Russell R. Waesche worked together to create a training program for merchant mariners. During the whole of the war, the schools of the War Shipping Administration, operated by the Coast Guard, would graduate nearly 32,000 officers and more than 230,000 seamen.

Once the U.S. was involved in the war, men too old or too young (in May 1944, the minimum age for a Merchant Mariner was lowered to 16) for the draft, or not accepted into the armed forces due to some disqualifying physical problem, found the Merchant Marine a suitable alternative to prove their patriotism. Besides, the pay was good. For example, in 1943 the average annual income for a U.S. Navy Seaman First Class was $1,886, while an Ordinary Seaman in the Merchant Marine made $1,897 per year. A Navy Petty Officer Second Class earned $2,308, as compared to a Merchant Marine Able Seaman, who made $2,132.

Some in the active duty military, however, resented the Merchant Mariners, calling them draft dodgers and mistakenly believing the civilians took home considerably more money. Such was not the case, and the men on the merchant ships faced no fewer hazards than the bluecoats serving aboard destroyers, cruisers, or aircraft carriers.

Although officially neutral, the United States in early 1941, under newly reelected President Roosevelt, was edging closer to involvement in the European crisis. Roosevelt knew that if Russia fell, Britain would likely be next, and then all of Europe would be dominated by the swastika. In response to the gloomy scenario, in March 1941, nine months before Pearl Harbor, the U.S. inaugurated the “Lend-Lease” program, which gave Britain, Russia, China, and other Allied nations vast amounts of war matériel with which to resist the Germans and Japanese. In the summer of 1940, Roosevelt had already sent a shipment of tanks, bombers, rifles, machine guns, and artillery pieces to Britain as a show of support—and in contravention of neutrality rules.

Lend-Lease grew out of Roosevelt’s friendship with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The prime minister told the president of Britain’s shaky economic situation and her inability to pay for and transport badly needed war materials. In a speech that likened Britain’s situation to a person who lends his next door neighbor a hose to extinguish a fire at his house, Roosevelt convinced the American people that it was in their best interests to support such a program.

American factories quickly geared up to produce the tanks, planes, bullets, bombs, shells, artillery pieces, canned food, and other items so desperately required by Hitler’s foes. Making these goods was one thing; getting them to the far-flung battlefronts was quite another. With airplanes insufficient to carry the heavy loads for such long distances, the only alternative was the sea, a 2,500-mile-long watery highway between the northeast coast of North American and Britain, even farther to Russia.

Through the use of spies and intercepted radio messages, the German Navy often was aware of what ships were leaving, when they were leaving, what they were carrying, and what routes they were going to use, and would station their U-boats about 15 miles apart along the expected shipping lanes. The first U-boat in a wolf pack to spot a convoy would signal the rest of the pack to assemble for the attacks, almost always carried out at night.

The Germans had quickly figured out that there was an “air gap” in the middle of the North Atlantic—beyond the range of Allied aircraft and dirigibles—that took ships several days to cross. The United States did have 112 long-range aircraft, which could have covered the air gap, but all were assigned to the Pacific. As a result, the German U-boat crews and commanders turned the gap into a happy hunting ground and began sending precious cargo and crewmen beneath the waves.

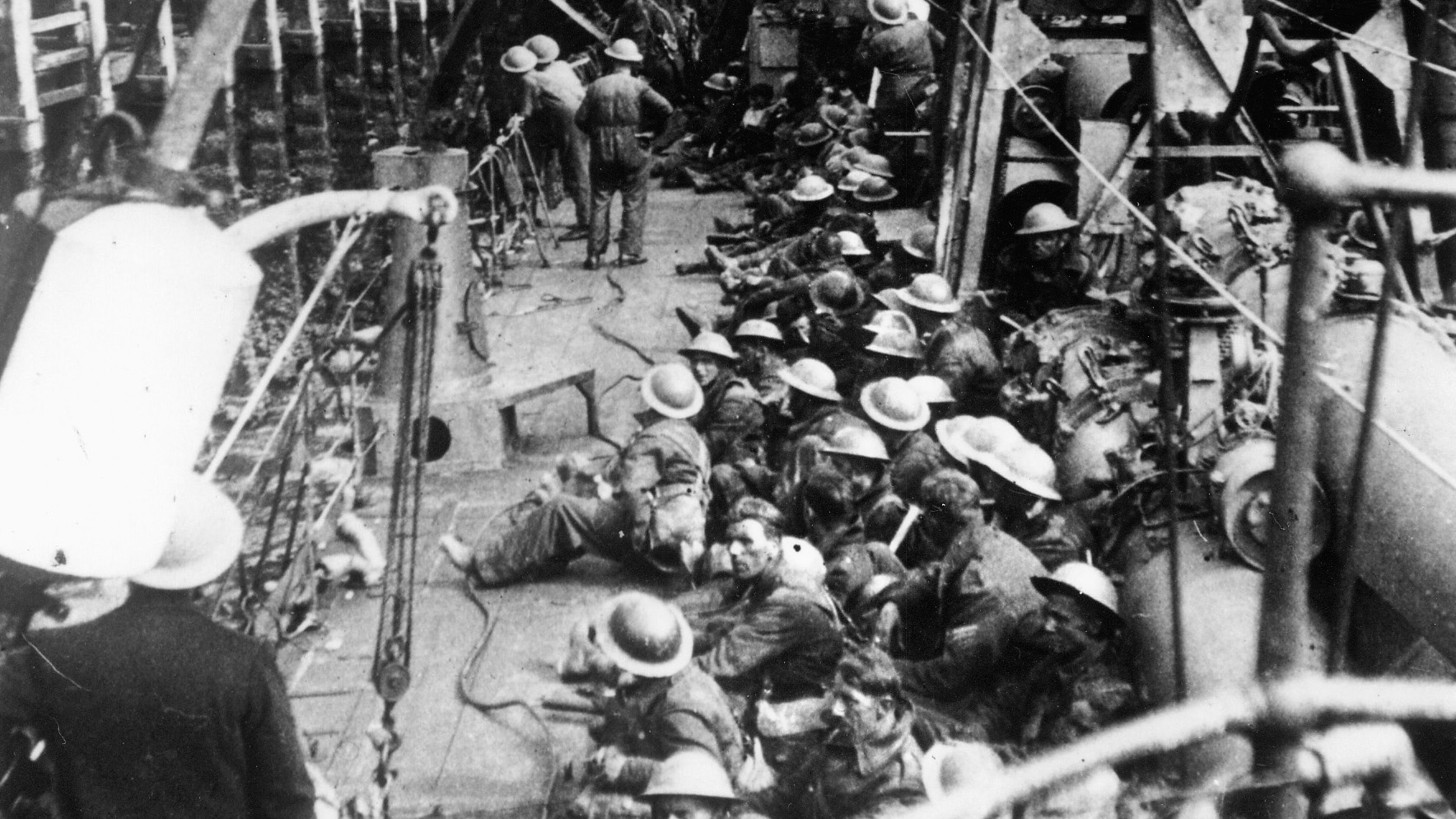

The stretch of ocean between Canada’s eastern provinces and Ireland was a favorite killing ground for U-boats, but the waters north of Norway were also especially dangerous. On June 8, 1940, the British aircraft carriers HMS Glorious and HMS Ark Royal and two destroyers were attacked while escorting a convoy of troopships evacuating British and Allied troops (along with the King of Norway) near Andenes Point, Lofoten Islands, Norway. In the furious sea battle that followed, Glorious was sunk by the German battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, with a loss of over 1,500 lives. Only 39 men survived.

On October 28, 1940, a 38-ship convoy, designated HX84, departed Nova Scotia bound for England. Eight days later, halfway between Newfoundland and Ireland, the German pocket battleship Admiral Scheer spotted the convoy and, like a wolf encountering a flock of sheep, the German warship moved in for the kill. Like a protective sheepdog, the HMS Jervis Bay, an armed merchant cruiser—basically a passenger liner outfitted with guns—escorting the convoy, set out to hold off the bigger ship while the rest of the convoy escaped. The Scheer ripped the Jervis Bay to shreds, sending her aflame beneath the waves, then went after the cargomen. Undeterred by the tanker HMS San Demitrios’s 6-inch deck guns, the Scheer’s 11-inch guns blasted away, setting the ship and her 11,200 tons of oil ablaze. The tanker nearly met the same fate as the Jervis Bay; by some miracle, the surviving crewmen were able to nurse the stricken vessel to safe port in Ireland.

Having Lulled Stalin Into A False Sense of Security, Hitler Aimed to Catch Stalin Off Guard

This early struggle on the high seas was a precursor of things to come, for not only were Canada and the United States providing aid to Britain, but soon they would be doing the same for the Soviet Union, their ally in the fight against Fascism.

By the autumn of 1941, Adolf Hitler saw himself as the master of Europe. His Third Reich had absorbed Austria and Czechoslovakia, and his armies had blitzed Poland, France, the Low Countries, Greece, Norway and Denmark. Spain and Italy were in Fascist hands, and Sweden and Switzerland had declared themselves neutral. Only Great Britain stood defiant, but Hitler was confident that the island nation would soon fall; the giant Soviet Union, whom Hitler regarded as his most formidable enemy, had been taken out of the game with his clever nonaggression pact, signed on August 23, 1939. Perhaps, having lulled Russia into a false sense of security, he could catch Josef Stalin by surprise. He did.

Now it was time to strike a massive blow that would finish off the Soviet Union, thus giving Germany nearly total control of the European continent. Hitler was sure that the neutral United States, full of antiwar sentiment, would stand on the sidelines, wring its impotent hands, make a few feeble protests, but do nothing to materially aid Russia, whose Communist form of government was anathema to most Americans.

The time was ripe. On June 22, 1941, Hitler, after postponing his planned invasion of Britain, launched Operation Barbarossa, a 3,200,000-man invasion of the Soviet Union. At first, the massive operation went smoothly, driving like a well-honed blade deeply into the heart of Mother Russia, inflicting huge casualties on the Bolshevik enemy and shoving Soviet defensive lines back to Stalingrad, Leningrad, and to the suburbs of Moscow. The situation looked desperate—and Stalin begged the United States for support.

It was a cry for aid that could not be ignored.

As author David Fairbank White writes in Bitter Ocean, “With no second front in the west to reinforce the Russians, struggling to push back Hitler’s assault, the Allies realized the critical importance of opening up a supply run to stoke and support Moscow’s defense. The Murmansk Run was as important to Russia’s survival and the final expulsion of the Nazis as any other Allied support. But the North Russia run was hell on ice.”

Despite his own nation’s precarious plight, Winston Churchill declared, “We shall give whatever help we can to Russia and the Russian people,” thereby opening the Arctic supply route to Russia.

While the Royal Navy began combat operations in July 1941 against German-occupied Norwegian ports, Britain was also preparing to send goods from Canada to the Soviets. The first of these convoys was code-named “Dervish” and consisted of seven merchant ships escorted by the carrier Victorious plus the cruisers Devonshire and Suffolk. On August 21, 1941, the convoy left Hvalfjord, Iceland, and arrived safely in the Russian port of Archangel 10 days later.

Surprised at the lack of German response, the British laid plans for more convoys. On September 29, the next outbound convoy, named PQ-1 (the convoy designation letters “PQ” for outbound trips and “QP” for return trips were chosen because the planning officer for the first convoy was Commander P.Q. Edwards), left Hvalfjord with 10 freighters escorted by the cruiser Suffolk and two destroyers. The convoy arrived safely in Archangel on October 11.

After an October meeting in Moscow, Britain and the United States promised to supply the Soviets with 400 planes, 500 tanks, 200 universal carriers, 22,000 tons of rubber, 41,000 tons of aluminum, 3,860 tons of machine tools, and large quantities of other strategic material per month, mostly by way of the Arctic route. The actual totals would fall short of the goals, but at least it was a start.

In October, PQ-2, bound for Archangel, got through without a loss. In November, Convoys PQ-3, PQ-4, and PQ-5 also made successful runs. By the end of December 1941, the Germans finally realized that the Allies were slipping goods into Russia through the back door and were determined to shut down the supply route. Dönitz, at the end of December, ordered the three-boat wolf pack “Ulan” to begin intercepting convoys.

About the same time, the British conducted two commando raids against German installations in Norway. These raids convinced Hitler that the Allies were planning to invade Norway, and he beefed up his naval, ground, and air forces there to meet the threat. Hitler noted, “The German fleet must… use all its forces for the defense of Norway. It would be expedient to transfer all battleships and pocket battleships there for this purpose…. Every ship which is not stationed in Norway is in the wrong place.”

As a result, the door slammed on the convoys at the beginning of 1942. Convoys PQ-7A, with two ships, and PQ-7B, with nine, were heading to Russia when the commander of U-134 spotted convoy PQ-7A and moved in for the attack, sinking the 5,135-ton steamer Waziristan, the first merchantman sunk on the Arctic Route. On January 17, the British destroyer HMS Matabele, escorting the eight-ship convoy PQ-8, was sunk off Murmansk by U-454, and only two men out of the crew of 200 survived; none of the merchantmen were lost.

In light of the increased submarine threat, PQs 9 and 10, with a total of 10 freighters, were combined and sailed on February 1 escorted by a cruiser and two destroyers. Along on the trip was a British rear admiral who was to meet with the Russians in Murmansk in an effort to persuade them to provide ships for convoy escort duty. He failed in his mission.

Churchill Believed That if the Tirpitz was Destroyed it Would “Profoundly Affect the Course of the War.”

As part of Hitler’s ordered redeployment, on February 12 the 31,100-ton battlecruisers Gneisenau and Scharnhorst, which had been plundering convoys in the Atlantic, plus the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, left their base at Brest, France, and sailed toward Norway through the English Channel, dodging English resistance. Both battlecruisers, however, struck mines and limped into a friendly port for repair; the Prinz Eugen, joined by the pocket battleship Admiral Scheer and three destroyers, made it to Norway. The British, relying on the top- secret Ultra intercepts of German communications, soon learned the Germans’ destination and alerted four submarines stationed off Trondheim. On February 23, one of these boats seriously damaged Prinz Eugen.

February 1942 was a lucky month for the convoys, for PQ-9, PQ-10, and PQ-11 all arrived at their Russian destinations safely. March was not quite as lucky. On March 1, the 16-ship PQ-12 set out from Reykjavik for Murmansk. The greatly feared German battleship Tirpitz, the sister ship of the Bismarck, was anchored at the Norwegian port of Aas Fjord, 15 miles from Trondheim, when it was joined by the Scheer. Worried about the growing strength of the German surface fleet, the Admiralty gave PQ-12 an unusually strong covering force, the battleships Duke of York and King George V, the battlecruiser Renown, and the carrier Victorious. Churchill had declared that the Tirpitz was “the most important naval vessel in the situation today” and believed that her destruction would “profoundly affect the course of the war.”

On March 5, German reconnaissance planes located Convoy PQ-12 and, the next day, with Hitler’s permission, Tirpitz and three destroyers left Aas Fjord, along with four U-boats on station in the area, to intercept PQ-12. A British submarine spotted the German flotilla and relayed the information back to London. Fortunately for the Germans, a storm hit the area and the Tirpitz, having been unable to locate PQ-12, headed back to her base. She was rediscovered off the Lofoten Islands and attacked by aircraft from the Victorious, but somehow escaped undamaged; PQ-12 arrived unscathed at Murmansk on March 12. The days of easy passage for the convoys, however, were over.

In late March, another severe storm raked the Barents Sea, scattering Convoy PQ-13 and its escorts and giving the Germans an opportunity to attack. On the 29th, three German destroyers north of Murmansk encountered the escort and, in the furious action that followed, a German destroyer was sunk and the British cruiser Trinidad was struck and damaged by one of her own malfunctioning torpedoes. Five of the 19 ships in PQ-13 were lost.

In April 1942, the 24-ship convoy PQ-14 sailed from Iceland but only seven ships reached their destination. One was sunk by a U-boat while 16 others turned back due to the weather; return convoy QP-10 lost four of its 16 ships to enemy attack at around the same time. Near the end of the month, convoy PQ-15 sailed for Murmansk under the protection of units of the Home Fleet, including the battleships King George V and the American USS Washington.

PQ-15 was a convoy riddled with errors and tragedy. On May 1, King George V rammed one of her escorting destroyers, Punjabi, and was then damaged by the latter’s depth charges as Punjabi sank with heavy loss of life. The next day, the minesweeper Seagull and Norwegian destroyer St. Albans mistakenly sank the accompanying Polish submarine Jastrzab. Then the Germans attacked and three of the merchantmen were lost to torpedo aircraft. Destroyers sank the escorting warship, the British cruiser HMS Edinburgh. The remaining 22 ships reached Murmansk on May 5, shaken but safe.

That month, a vexed Stalin sent a long list of war supplies to Churchill with a note: “I am fully aware of the difficulties involved and of the sacrifices made by Great Britain in the matter [of the Russian convoys]. I feel, however, incumbent upon me to approach you with the request to take all possible measures in order to ensure the arrival of the above-mentioned materials in the USSR.”

Such a message prompted the prime minister to step up efforts to aid the Soviets. Churchill declared the effort would be worthwhile even if only half the merchantmen got through. Simultaneously, the Germans, worried that too many convoys were reaching their destinations, ramped up their efforts to halt the flow of goods.

On May 26, in the Barents Sea north of Norway, Convoy PQ-16 was traveling to Murmansk with 35 ships. Suddenly, some 260 Luftwaffe aircraft, including Heinkel He-111 bombers armed with torpedoes, came swarming down from the sky while U-boats, their periscopes brushing aside floating chunks of arctic ice, joined in the attack. In a running battle that lasted six days and nights, the convoy and its escorts desperately fought off the enemy raiders but lost 11 ships in the process. Twelve freighters made it to Murmansk and the remaining eight to Archangel. As terrible as the PQ-16’s losses were, the next convoy would suffer an even worse fate.

In late June 1942, the 37-ship convoy PQ-17, the largest and most valuable convoy to date, formed at Hvalfjord, Iceland, and began to make its run to Murmansk and Archangel. Crammed into the holds of the cargomen were tanks, trucks, aircraft, boxes of ammunition, and other vital supplies destined for the hard-pressed Red Army. The Germans were determined that PQ-17 would not pass and instituted Operation Rösselsprung that would add surface ships—the Tirpitz, Scheer, and Hipper—to the intercepting force.

On July 1, two U-boats attempted to attack the convoy but were chased off by British and American escorts; eight more U-boats began stalking PQ-17, waiting for the right moment to strike. That evening, Norway-based German aircraft swooped down on the ships but were driven away by a fierce storm of antiaircraft fire.

On July 4, with PQ-17 over 400 miles from the nearest Soviet landfall, the battle was again joined. The Luftwaffe pounced on the convoy, which somehow managed to maintain formation and discipline. Then submarines struck, and the brand new Liberty Ship USS Christopher Newport, crippled by aerial torpedoes, was sunk by the U-457.

Focke-Wulf 200 Condor long-range bombers torpedoed four more ships, sinking two. Next, 25 He-111 torpedo bombers pounded the Liberty ship William Hooper, which was abandoned by her crew without orders. In London, fearful that the three German battleships might arrive and sink the entire convoy, First Sea Lord Sir Dudley Pound ordered his armed escorts to withdraw. At 9:23 pm, he also ordered PQ-17 to disperse, without escort. A few minutes later, Pound told the convoy “to scatter” and to proceed to their destinations individually. This order would doom PQ-17.

“The Ships are Now Going Around in Circles, Turning This Way and That, Like so Many Frightened Chicks.”

The naval escort of four cruisers and six destroyers did as ordered, left the freighters, and headed south. The merchant ship captains watched in horrified astonishment as their escorts departed—the military equivalent of a man walking his date home through a dangerous neighborhood, only to abandon her when approached by muggers and rapists. The force was now on its own.

“We hate leaving PQ-17 behind,” wrote the film star Lieutenant Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., who was aboard the cruiser USS Wichita. “It looks so helpless now since the order to disperse has been circulated. The ships are now going around in circles, turning this way and that, like so many frightened chicks. Some can hardly go at all.”

A Soviet tanker sailing with the convoy, the Azerbaijan, was hit and set on fire but managed to maintain power and continue on. At 10:15 pm on the 4th, the convoy was hit again. But PQ-17 could not slip away into the darkness, because there was none at this time of year, and at this latitude, daylight lasts 24 hours day.

With no protection, Convoy PQ-17 was a sitting duck. The Luftwaffe caused the most damage, with the U-boats assisting. Tirpitz and the other German dreadnaughts left their Norwegian anchorage to join in the action, but it was determined they were not needed and they reversed course.

The German victory was nearly complete. Of the 37 PQ-17 ships that had sailed from Iceland, two had turned back earlier, eight were sunk by aerial bombs and torpedoes, nine were sunk by U-boats, and a further seven were sunk by U-boats after having been left dead in the water by air attack—a total of 24 ships lost. Going down with the dying freighters was a large portion of the $700 million worth of equipment—430 tanks, 210 crated aircraft, 3,350 vehicles, and 99,316 tons of general stores—along with 153 merchant seamen. Of the debacle, Churchill said, “PQ-17 was one of the most melancholy episodes of the war.”

Two weeks later, the German Army in Russia launched a successful summer offensive; could the Soviets have held out had those supplies, now lying at the bottom of the Barents Sea, reached them? One will never know. The abandonment of Convoy PQ-17 by its escorts was a disgrace that haunts the Royal Navy to this day.

In September, the Germans set their sights on the next convoy, PQ-18. Thirty-nine merchantmen, three minesweepers, one oiler, and one rescue ship sailed from Loch Ewe on September 2, 1942, under the protection of a huge escort fleet that numbered 57 warships and nine submarines. During a week-long battle, the Germans lost six U-boats and 41 aircraft. All but 13 of the escorted vessels got through to Kola Inlet.

Accurate figures are hard to come by but, by any analysis, 1942 was the U-boats’ most successful year. One source says that 1,664 Allied ships were sunk, 1,097 of them in the North Atlantic. Losses to German assets were minimal. Although Liberty ships were sliding down the ways in shipyards around the country at a rate of three per day, it still was not enough. In 1942, the Allies launched 11 million tons of new ships, eight million built in the United States, but had lost 12 million tons to the enemy. In November alone, the Allies lost more than 800,000 tons of shipping, more than half of which was in the North Atlantic.

The Murmansk Run was halted temporarily as shipping was urgently needed to support Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa, in November 1942.

During the winter lull of 1942-43, the Germans took the opportunity to repair and refit many of their warships. The Tirpitz was at Trondheim, undergoing overhaul. The pocket battleship Lützow had arrived from the Baltic in Altenfjord on December 18 to relieve the Scheer, which had returned to Germany for refit in early November. That left the Hipper and the cruiser Köln as the only large warships in Norwegian waters. Scharnhorst, Prinz Eugen, and five destroyers were scheduled to transfer from the Baltic to Norway in January.

After nearly a three-month winter hiatus, the Allied convoys resumed in December 1942 with the convoy designation numbers changed from PQ and QP to JW (outbound) and RA (return), and the sequencing began with JW-51A. Convoy JW-51B left Loch Ewe on December 22 while JW-51A arrived in Murmansk on Christmas Day 1942 without loss. Convoy JW-51B—14 American and British ships loaded with 2,046 vehicles, 202 tanks, 87 fighters, 33 bombers, 11,500 tons of fuel, 12,650 tons of aviation fuel, and over 54,000 tons of general cargo—would become famous as “the convoy that sank a navy.”

On the 28th, a huge storm hit the region, and JW-51B became scattered, only to find itself within 200 miles of the German base at Altenfjord.

On that same day, Hitler, never a great supporter of his navy, was haranguing his admirals: “Our own navy is but a copy of the British—and a poor copy at that. The warships are not in operational readiness. They are lying idle in the fjords, utterly useless, like so much old iron.”

When Told of Losing a Destroyer in the Battle of the Barents Sea, Hitler Flew into a Rage and Ordered the German Fleet to be Scrapped

Part of the problem was of Hitler’s own making; he specifically forbade his large ships from attacking convoys, telling his admirals they were to be kept in reserve and used only to repel the expected Allied invasion of Norway. Once he learned of the approach of Convoy JW-51B, however, he countermanded his order and permitted the use of the battle fleet to sink it. Hipper and Lützow, however, were not to be used in a sea engagement, lest they be lost. Instead, six destroyers and a fleet of U-boats were to sail from Altenfjord on December 30 to intercept JW-51B. Hipper and Lützow would stand just beyond range of British guns and out of harm’s way. The Hipper did lob a few shells at a British destroyer, HMS Onslow, causing heavy casualties, and sank the destroyer HMS Achates. Both the Hipper and Lützow could have inflicted greater damage on the convoy, but both commanders were too afraid of disobeying the Führer’s order.

The British cruisers Jamaica and Sheffield took the Hipper under fire, with one six-inch shell from Sheffield and two from Jamaica striking the German warship, which quickly withdrew. A German destroyer was sunk by the Sheffield in the action, which became known as the Battle of the Barents Sea. Hipper and Lützow retreated back to Altenfjord with their five remaining destroyer escorts while JW-51B sailed on to its destination. When given the news, Hitler flew into one of his typical rages and made the snap decision that the German fleet should be scrapped. Admiral Erich Raeder, commander of the Kriegsmarine, tendered his resignation and was replaced by Admiral Karl Dönitz.

The year 1943 was a watershed year that finally saw the momentum of war swing over to the Allied side. February 1943 saw the Red Army utterly destroy the German Sixth Army at Stalingrad, and the gods of war began to smile on the Allies.

In combination with improved antisubmarine warfare techniques, including new, sub-killer weapons such as the Mark 24 acoustic aerial torpedo and the 24-barrel ship-launched mortar known as the “hedgehog,” the Allies were slowly gaining the upper hand.

In 1943, the United States became fully engaged in the land war against the Germans. Following the invasion of North Africa, the U.S. Army gained confidence on the ground and helped the British end the Axis threat there in May. This victory was followed by the successful invasion and expulsion of enemy forces from Sicily in July, soon to be eclipsed by the amphibious assault on Italy proper.

Early war plans had also called for 1943 to be the year when a cross-Channel invasion of France from England to relieve German pressure on the Soviet Union would be launched but, with so many ships tied up to support the Mediterranean Theater and the massive build-up men and equipment in England, the invasion was pushed back to 1944.

After running one convoy each in January and February, the shipments to Russia through the Barents Sea were temporarily suspended. The suspension was to allow the pivotal Battle of the North Atlantic to take place from March 12-17, 1943. Convoys HX229 and SC122—88 merchant ships and 15 escorts—were bound for Europe from New York, via Halifax, Nova Scotia, on parallel courses. Lying in wait for them were 42 U-boats. During the running battle that lasted five days and nights, the Germans fired 90 torpedoes and sank 22 merchantmen totaling 141,000 tons. Only one U-boat was lost and three damaged. German officials called it the “greatest convoy battle of all time.”

The Allies agreed. “The Germans never came so near to disrupting communication between the New World and the Old as in the first twenty days of March 1943,” soberly admitted the British Admiralty. During the first three weeks of March, the Allies had lost 97 merchant ships and escorts, for a total of 500,000 tons.

This was a situation that could not continue; the Murmansk Run was suspended until September in order for the menace in the North Atlantic to be dealt with. Roosevelt ordered Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, commander in chief, United States Fleet and chief of Naval Operations, to transfer 60 Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers from the Pacific to the North Atlantic to halt the depredations by the U-boats. The antisubmarine offensive proved successful; in May, 18 of 49 U-boats operating in the North Atlantic were sunk and, on May 22, Admiral Dönitz halted submarine operations in the area.

In September 1943, the British Admiralty decided to stop worrying about the Tirpitz and do something about her. An earlier secret mission to blow up the battleship in October 1942 failed when an attack by small human torpedoes was aborted at the last minute. A new mission, using midget subs, was mounted. On September 20, the submarines X-6 and X-10 slipped into Kaafjord, at the far end of Altenfjord, and set off charges beneath Tirpitz’s hull. Although the midgets sank and some of their crewmembers were killed, the battleship was heavily damaged and put out of commission.

American shipyards in 1943 were hitting their stride and delivered 20 million tons of new merchant ships. In late 1943 and early 1944, American shipbuilders switched from constructing Liberty ships to building “Victory” ships.

Victory Ships Measured 455 ft. and Cranked Out Between 5,500 to 8,500 Horsepower

Learning lessons from the shortcomings of the Liberty ships, the Victory ship designers set the frames inside the hull 36 inches apart as compared to the 30 inches of spacing in the Liberty ships. Such a change made the Victory ships’ hulls more flexible and less likely to split apart, as had happened with numerous Liberty ships under attack or when the steel turned brittle in sub-zero conditions. The first Victory ship to be completed and launched was the SS United Victory, which slid down the ways of a Portland, Oregon, shipyard on January 12, 1944.

The Victory ships were slightly bigger and faster than the Liberties, powered by steam turbines that cranked out between 5,500 to 8,500 horsepower. Their cruising speed was 15-17 knots (approximately 18.5 miles per hour). Each one was 455 feet in length and had a beam of 62 feet. Like the Liberty ships, each had five cargo holds. Each could carry 10,850 deadweight tons, or 4,555 net tons. Typically, a Victory ship had a crew of 62 civilian merchant sailors and 28 naval personnel.

The shipyards’ output was tremendous: a total of 414 Victory cargo ships and 117 Victory attack transports would be built during the last 18 months of the war.

With the German Navy feeling the pinch of the Allies’ concentrated counteroffensive, convoy after convoy made the Murmansk Run in the fall and winter of 1943 without losing a single ship to enemy action.

On December 26, during the Battle of the North Cape, perhaps the northernmost battle ever fought, the battlecruiser Scharnhorst, after attempting to attack Convoy JW-55B, was hit by British warships and sunk.

In 1944, the Germans renewed their attempt to cut off the flow of goods to Russia, but it was a feeble attempt. U-boats were being sunk by the dozen. Only five merchant ships were lost in January and none in February, March, or April.

In March, the Admiralty decided to have another go at Tirpitz, which was nearly finished with her repairs. A Fleet Air Arm attack, supported by battleships, was mounted, and the Tirpitz took 14 bomb hits but did not sink. The damage, however, was enough to keep her out of action for another three months. Subsequent aerial attacks against her were dismal failures, but on November 12, 1944, RAF heavy bombers finally succeeded in sinking her, lying at anchor in a fjord near Tromso. Over 1,000 of her crew were trapped inside her capsized hull and lost.

In May, U-boats sank one ship out of 45 in return convoy RA-59, but three U-boats paid the price. In June, the long-awaited Allied invasion of Normandy took place, sounding the death knell for the Third Reich. Still, the shrinking number of U-boats carried on, sinking a handful of cargomen and escort ships in August and October 1944, and February and March 1945.

The final battle of the convoys took place on April 29, 1945. Convoy JW-66 (22 ships) had arrived safely at the Kola Inlet while the return convoy, RA-66, was attacked by 14 U-boats lying in wait outside the inlet. In the action, the British frigate Goodall took a torpedo and went down with heavy loss of life—the last major warship of the Royal and Dominion Navies lost in the war against Germany. Two U-boats were sunk. RA-66 arrived safely in the Firth of Clyde, Scotland, on May 8, 1945. By then, Hitler was dead, Nazi Germany was no more, and the war in Europe was at last over.

The legacy of the U.S. Merchant Marine in World War II is one mixed with pride and sorrow. Worldwide, approximately 8,300 Merchant Marines died at sea. Another 12,000 were wounded, of whom at least 1,100 died from their wounds; 663 men and women were taken prisoner. One in 26 Mariners serving aboard merchant ships in World War II died in the line of duty—a greater percentage of war-related deaths than all other U.S. services.

The records of the Arming Merchant Ships Section of the Fleet Maintenance Division of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations show that some 347 merchant ships were dispatched to North Russia from August 1941 through April 1945. Most of the losses were sustained between January 5, 1942, and March 14, 1943. In this period 143 ships departed for North Russia and 111 arrived. These figures illustrate that about one out of every three ships was lost. According to the records of the War Shipping Administration, after this early period of heavy losses, only 10 ships out of more than 200 were lost on the North Russia run for the remainder of the war.

The Royal Navy also suffered. The cost included one escort carrier severely damaged, two cruisers, six destroyers, and numerous other escorts sunk in the frigid and often stormy waters of the Arctic. Thirty thousand British merchant seamen, about 25 percent of those in the British Merchant Marine, died in the North Atlantic. Yet, their sacrifice and devotion to duty meant that millions of tons of vital cargo were delivered to the Soviets, enabling them to fight off the German invaders. All played an important role in the eventual Allied victory and must not be forgotten.

On the German side, the losses in submarine crews were staggering. Some 28,000 enlisted U-boat crewmen died out of a total of 40,000, and more than 713 U-boats were sunk. The Germans also lost Scharnhorst and, indirectly, Tirpitz, among other ships and aircraft.

The Liberty ships and their cousins, the Victory ships—and all those who built them—also must never be forgotten. Between 1939 and 1945, the U.S. Maritime Commission ordered 5,777 ships of all types totaling 56.3 million deadweight tons, or almost five times the size of the nation’s entire 1939 fleet—the greatest construction of ships ever undertaken in history. Had it not been for these ships and their courageous crews, it is probable that the war would have lasted many months, if not years, longer, and perhaps had a different outcome.

41 Murmansk Run Convoys, $18 Billion in Cargo

Between 1941 and 1945, a total of 41 convoys made the Murmansk Run carrying an estimated $18 billion in cargo from the United States, Great Britain, and Canada. Among the millions of tons of supplies were an estimated 12,206 aircraft, 12,755 tanks, 51,503 jeeps, 300,000 trucks, 1,181 locomotives, 11,155 flatcars, 135,638 rifles and machine guns, 473 million shells, 2.67 million tons of fuel, and 15 million pairs of boots.

The last Liberty ship was built in June 1945, and almost all of them are now gone. Most were broken up for scrap, some were cut up and reassembled into barges for the coastal trade, and a few were deliberately sunk in shallow waters to serve as artificial reefs for fish habitats.

Only two are known to survive intact. The Jeremiah O’Brien is docked at Pier 45, Fisherman’s Wharf, San Francisco, where it serves as the National Liberty Ship Memorial. In 1994, it sailed to and from Normandy to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Operation Overlord. Several times each year, volunteers fire up one of the original boilers and cruise around the bay.

The only other remaining Liberty ship is on the East Coast, the John W. Brown, moored in Baltimore Harbor and operated as a museum.

In 1944, the GI Bill gave members of the Armed Forces who served at least 90 days anywhere between December 7, 1941, and December 31, 1946, major benefits such as educational assistance, home loans, and job preferences. As he signed the historic bill, President Roosevelt said, “I trust Congress will soon provide similar opportunities to members of the Merchant Marine who have risked their lives time and time again during war for the welfare of their country.”

Unfortunately, the Merchant Marine was not accorded such opportunities for many decades. Opposition by some in the military, and pressure from groups such as the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars who still believed the myth that the Merchant Mariners were overpaid for their wartime services stood in the way. As of 2006, the VFW still refuses to recognize Merchant Mariners as veterans of World War II, even though the U.S. government does; in 1985, those who served in the Merchant Marine were given official U.S. Coast Guard discharges and granted veteran’s status.

Each year, on or around May 22, National Maritime Day, the Maritime Administration sponsors a Merchant Marine Memorial Service, which honors American seafarers who lost their lives in service to their country.

President Roosevelt paid homage to the unflagging efforts of Merchant Mariners when he said, “[Mariners] have delivered the goods when and where needed in every theater of operations and across every ocean in the biggest, the most difficult and dangerous job ever undertaken. As time goes on, there will be greater public understanding of our merchant fleet’s record during this war.”

Denver-based Flint Whitlock is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He has authored four books and dozens of articles on World War II and is working on a history of American submariners.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments