By Roy Morris, Jr.

Mr. Morris is the author of seven well-received books on 19th Century American history and literature. He has served as a consultant for A&E, the History Channel, and edited a three-book series for Purdue University Press on American Civil War and post-Civil War history, journalism and literature. His work has been reviewed in the New York Times Book Review, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, the International Herald Tribune, New Yorker, Atlantic Monthly, Boston Review of Books and New Leader, as well as many leading newspapers across the country and abroad. In addition to the Smithsonian Institution, he has also spoken at the National Portrait Gallery, the National Arts Club in New York City, the Atlanta History Center, the Flagler Museum in Palm Beach and the Northern Trust in Miami.

Ulysses S. Grant

Not only did Grant win the first major turning-point battle of the war, at Fort Donelson, he also prevented the South’s first and best attempt at reversing that turning point, at Shiloh. He then captured Vicksburg, clearing the way for Union control of the Mississippi; broke the Confederate siege at Chattanooga; and appointed strong and capable subordinates in William T. Sherman and Phil Sheridan. He fought Robert E. Lee to a standstill in the Battle of the Wilderness, bottled up Lee’s army at Petersburg, and caught up with it at the Battle of Appomattox, winning the Civil War in the process.

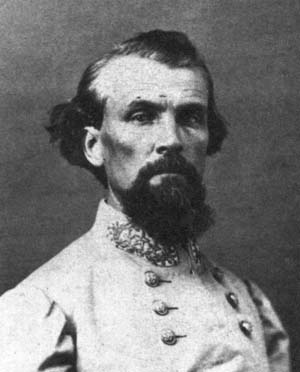

Nathan Bedford Forrest

No less a judge than Robert E. Lee reportedly said that the Confederacy’s best general was “a man I have never met. His name is Forrest.” Lee was right. The fierce, unrelenting genius of Forrest prefigured modern warfare, with its emphasis on the enemy’s army, not his territory. “War means fighting and fighting means killing,” Forrest said. He did not say, illiterately, “Git thar fustest with the mostest,” but his concept of highly swift, mobile forces, seen most clearly in his overwhelming victory at Brice’s Crossroads, is still studied by military leaders. Perhaps the highest tribute to Forrest’s self-taught ability as a commander was the fact that Forrest was the only Confederate cavalryman whom Ulysses S. Grant or William T. Sherman feared.

Abraham Lincoln

The commander-in-chief of Federal forces during the Civil War, Lincoln had very limited military experience as a volunteer in the Black Hawk War. Being a genius, however, allowed him to master virtually every situation he was in, including war. He clearly saw both the larger outlines and the smaller details of the Union war effort, and he seldom suggested a military course that was not logical and well-considered. Lincoln made his share of mistakes in choosing generals, but he was much quicker than his Confederate counterpart, Jefferson Davis, in recognizing his mistakes and correcting them. When he finally found a commander in Ulysses S. Grant who was as relentless as he was in prosecuting the war, he had the good judgment to let him to it.

Robert E. Lee

Possibly rated too high, given the fact that Lee fundamentally misunderstood the most basic aim of the Confederacy, which was to survive until it got stronger, gained foreign recognition, and came to seem a factual inevitability. His two misguided invasions of the North, besides giving up the South’s moral high ground as an invaded country, bled dry his matchless army, ultimately eliminating its ability to fight on anything like even terms with the North. Lee also commanded badly at the Battle of Gettysburg, the most important battle of the war, and his decision to make a final frontal assault with Pickett’s division surely remains one of the worst and least defensible decisions a great commander ever made. When Lee told the survivors, “It is all my fault,” he was not being noble—he was merely stating the obvious.

Patrick Cleburne

The quiet, gentlemanly, Irish-born Cleburne was a superb commander at the regimental, brigade, division and corps levels. He excelled at both offense and defense, and he never failed to fulfill his assigned role in any battle in which he took part. His unconventional and unpopular advice to arm southern slaves and allow them to fight for their freedom fell on deaf ears, and resulted in the stagnation of Cleburne’s career. (Whether or not this would have worked is debatable, but by that time in the war it would have been worth a try.) No other Civil War general ever went to his death more clear-eyed and unillusioned than Patrick Cleburne at Franklin, which is a pretty good definition of true heroism. “We will do our duty,” he said—and did.

The quiet, gentlemanly, Irish-born Cleburne was a superb commander at the regimental, brigade, division and corps levels. He excelled at both offense and defense, and he never failed to fulfill his assigned role in any battle in which he took part. His unconventional and unpopular advice to arm southern slaves and allow them to fight for their freedom fell on deaf ears, and resulted in the stagnation of Cleburne’s career. (Whether or not this would have worked is debatable, but by that time in the war it would have been worth a try.) No other Civil War general ever went to his death more clear-eyed and unillusioned than Patrick Cleburne at Franklin, which is a pretty good definition of true heroism. “We will do our duty,” he said—and did.

Stonewall Jackson

Old Blue Light was one of the great eccentric geniuses of the Civil War–or any other war. Like his closest counterpart in the western theater, Nathan Bedford Forrest, Jackson understood the relentless logic of war. When his men held back from shooting the bravest Union soldiers attacking them out of misguided admiration, Jackson told them those were precisely the soldiers they should be killing. Jackson stumbled at Kernstown and the Seven Days’ Battles, but his Shenandoah Valley campaign is rightly considered one of the outstanding military feats in American military history. He won the Battle of Chancellorsville for Robert E. Lee, and it is certainly arguable that he would have done the same thing at Gettysburg, had he lived. Indeed, with the exception of Cold Harbor, which any competent general could have managed, Lee never won another major battle after Jackson was killed.

Phil Sheridan

The unlovely, unlikable Sheridan was an absolute bulldog on the battlefield, and he excelled at every level. Few generals on either side took part in as many major battles, in both the eastern and western theaters, as Sheridan. He commanded cavalry in Mississippi early in the war before moving over to the infantry, where he played notable roles at Perryville, Stones River, the Battle of Chickamauga and Missionary Ridge, before joining his mentor, Ulysses S. Grant, in Virginia. His independent command of the Army of the Shenandoah brought crucial victories at Winchester, Fisher’s Hill and Cedar Creek, and his return to the battlefield at the latter engagement became one of the legendary feats of the war. His relentless pursuit of Lee’s army helped shorten the war and saved lives by inducing the Confederate chieftain, however reluctantly, to face the inevitable and surrender at Appomattox.

George B. McClellan

Little Mac had his glaring weaknesses as a general, chief among them a humane reluctance to sacrifice the lives of his own men, but no one ever questioned his ability to organize and train an army. The creation, from the ground up, of the Army of the Potomac was a great personal feat and a crucial contribution to the Union war effort. In using his army to defeat the enemy, McClellan was cautious, but not nearly as slow as his critics have maintained. He failed to capture Richmond in the Peninsula Campaign, but he brought the battle to the very outskirts of the Confederate capital, and he won his share of the Seven Days’ Battles. Most importantly, McClellan won the Battle of Antietam—perhaps the true turning point in the war. His opponent, Robert E. Lee, always said that McClellan was his toughest opponent.

Little Mac had his glaring weaknesses as a general, chief among them a humane reluctance to sacrifice the lives of his own men, but no one ever questioned his ability to organize and train an army. The creation, from the ground up, of the Army of the Potomac was a great personal feat and a crucial contribution to the Union war effort. In using his army to defeat the enemy, McClellan was cautious, but not nearly as slow as his critics have maintained. He failed to capture Richmond in the Peninsula Campaign, but he brought the battle to the very outskirts of the Confederate capital, and he won his share of the Seven Days’ Battles. Most importantly, McClellan won the Battle of Antietam—perhaps the true turning point in the war. His opponent, Robert E. Lee, always said that McClellan was his toughest opponent.

George H. Thomas

Thomas’s reputation suffered during and after the war because he was not a part of the inner circle of Grant, Sherman and Sheridan. He also hurt his cause by twice declining to accept command of the main Union army in the west when it was offered to him. The fact that he was a native-born Virginian also handicapped Thomas, despite his undeniable loyalty to the Union. Still, he won the first major Union victory of the war at Mill Springs, Ky., and his stubborn stand at Chickamauga prevented the utter decimation of the Federal forces there. His men then took Missionary Ridge (not Grant’s original plan), and at Nashville, Thomas won perhaps the most overwhelming victory of the war. Unlike any of the other generals on this list, he never turned in a poor performance.

William T. Sherman

Sherman has always been overrated as a battlefield commander. He tended to be shaky in times of stress, and he came close to single-handedly losing the Battle of Shiloh by carelessly neglecting to picket his position. He completely failed to take Missionary Ridge, which his good friend Ulysses S. Grant badly wanted him to do, and his frontal assaults at Kennesaw Mountain and Pickett’s Mill were murderously ill-considered. Nevertheless, Sherman deserves credit for helping Grant take Vicksburg, and his capture of Atlanta in the late summer of 1864 may well have saved the presidency for Abraham Lincoln—a not inconsiderable accomplishment in itself. His subsequent March to the Sea, although not nearly as destructive as legend has it, nevertheless brought the war to the doorsteps of southern civilians and helped convince them that further resistance was futile. He could probably have been elected president in 1876, had he not refused to accept the Republican nomination.