by Rick Beard

Contrary to popular belief, slavery in America was a subject of much contention long before the Civil War. For over a century before the American Revolution, it began to grow incrementally.

[text_ad]

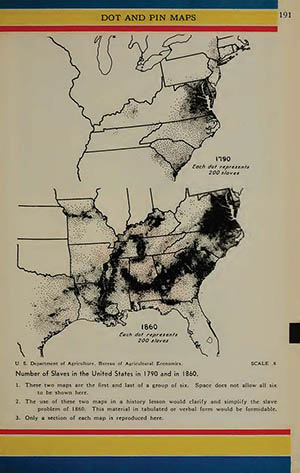

In 1641, Massachusetts became the first British colony to legalize slavery. Connecticut followed in 1650, Maryland in 1663, New York and New Jersey a year later, and Pennsylvania in 1700. In the eight decades following 1620, no more than 21,000 enslaved Africans arrived on the Continent, but this would be a modest total by later standards. By 1700, the slave population of the American colonies totaled 28,958, about 72 percent of whom lived in the Chesapeake region and Upper South.

Plantation Culture Grows

Over the course of the 17th century, plantation agriculture came to dominate the colonial American economy. Tobacco, introduced into the Chesapeake region in 1612, became a pathway to great riches. Virginia planters exported 500,000 pounds to London in 1628 alone, but 11 years later, that number had risen to 1.5 million pounds. By 1700, it would be over 20 million. Growing tobacco was grueling work, and planters quickly learned that reliance on enslaved Africans was essential to their success.

Over the course of the 17th century, plantation agriculture came to dominate the colonial American economy. Tobacco, introduced into the Chesapeake region in 1612, became a pathway to great riches. Virginia planters exported 500,000 pounds to London in 1628 alone, but 11 years later, that number had risen to 1.5 million pounds. By 1700, it would be over 20 million. Growing tobacco was grueling work, and planters quickly learned that reliance on enslaved Africans was essential to their success.

For their part, slave merchants in Great Britain and on the European continent were enthusiastic in responding to the Western Hemisphere’s appetite for slave labor. The vast majority of the 5.8 million Africans who arrived during the 18th century were not brought to British North America, but to the Caribbean and South America. Nevertheless, the numbers arriving in North America between 1700 and 1750, almost 146,000, accounted for a 750 percent increase in the slave population, up to 246,648.

Armed Revolts & Civil Upsets

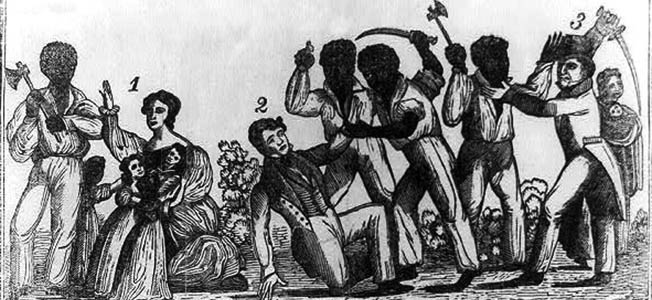

However, the planters’ increasingly oppressive control over their slaves did not go uncontested. Black people carved out small spheres of personal freedom, in rare cases earning cash with which to buy their freedom. In several instances, slaves mounted armed revolts. Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676 pitted English colonists and Africans in a rare alliance against royal authorities in Virginia. The Natchez Rebellion of 1731 squelched French plans in the lower Mississippi Valley to institutionalize and expand slavery.

Actually, two of the most famous uprisings occurred within two years of one another: in 1739, enslaved Angolans in South Carolina launched the Stono Rebellion, murdering two dozen whites while attempting to reach Spanish-controlled St. Augustine, where a more tolerant regime allowed Africans freedom, pending production and military service. Two years later, the failed Negro Plot in New York City led to the execution of 30 blacks and four whites, as well as the banishment of another 70 blacks and seven whites.

The American Revolution

By the American Revolution, forces were set in motion to disrupt and transform slavery in the new nation. This occurred most dramatically in the northern states: Pennsylvania introduced gradual emancipation in 1780, and Massachusetts courts outlawed slavery three years later. By 1803, all the northern states had provided for the gradual abolition of slavery and had liberalized manumission laws.

In 1787, when the new nation’s leaders met in Philadelphia to draft a governing charter, the country’s different patterns of slaveholding demanded a compromise. Unfortunately, the Constitution drafted failed to fulfill the implied promise of freedom and equality that had inspired both free and enslaved blacks during the Revolutionary War. American slavery now enjoyed greater legal protection than at any other time in the nation’s history. Its favored status within the Constitution soon led to serious social, economic and political divisions. The American Civil War was well on its way.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments