By Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

In 376 AD the Goths appeared on the lower Danube frontier of the Roman Empire. They came as a whole tribe, with warriors, women and children. They came on foot, on horseback, and in lumbering ox-drawn wagons, refugees on the retreat from a foe even fiercer than themselves. They came knocking on the Roman door.

A Germanic people and originally of Scandinavian origin, the Goths migrated from their homeland in eastern Germany to the shores of the Black Sea in the late 2nd century ad. In 247 ad their raids on the Roman Empire began in earnest. On land and sea, the Goths spread terror for nearly a quarter of a century and defeated the Roman army of Emperor Decius, who was killed in battle against the invaders.

The Romans managed to contain the Gothic threat, but the western branch of the Goths, the Visigoths (“wise Goths”) pushed into the abandoned Roman province of Dacia (Transylvania). Not until the reign of Constantine the Great was a lasting peace procured with the Visigoths. They became federates of the Empire, which they were obliged to protect in exchange for yearly monetary subsidies. To the east of the Visigoths, the Ostrogoths (“bright Goths”), under their great King Hermanic, built up a vast empire of barbarian peoples that stretched from northeast of the Dniester to the shores of the Baltic.

The nominally peaceful relations between Goth and Roman continued for about half a century. War resumed in 364, however, when the Visigoths interfered in a Roman civil war. But the rightful heir to the East Roman Empire, Emperor Flavius Julius Valens, not only managed to squash the usurper to his throne but drove the Goths back north across the Danube and pursued them into their homelands.

As it turned out, the latest Gothic incursions were but a tremor compared to the earthquake that was unleashed with the appearance of the Huns, a pastoral Mongoloid people who roamed the steppes between the Caspian and Aral seas. Political turmoil in their own lands caused the Huns to press toward Eastern Europe.

‘Desperate and Dangerous’ After Being Defeated by the Huns

Like the Goths, the Huns were not numerous, but relied on cunning, brutality, terror, and above all the speed and endurance of their sturdy ponies. In 372 they routed the Alans, a nomadic people of Iranian or Turkish origin, from their homeland north of the Caucasus and south of the river Don. The armies of Hermanic were next to fall; the old king slew himself in despair. Neither his successor nor the Visigoths were able to stop the Huns, whose swift mounted archers cut down the Goth infantry from afar.

Like the Goths, the Huns were not numerous, but relied on cunning, brutality, terror, and above all the speed and endurance of their sturdy ponies. In 372 they routed the Alans, a nomadic people of Iranian or Turkish origin, from their homeland north of the Caucasus and south of the river Don. The armies of Hermanic were next to fall; the old king slew himself in despair. Neither his successor nor the Visigoths were able to stop the Huns, whose swift mounted archers cut down the Goth infantry from afar.

Their defeat at the hands of the Huns caused great turmoil among the Goth subtribes. Many became subjects of the Huns while others wandered west. The more anti-Roman and anti-Christian factions of the Visigoths pushed into the Carpathians, but the bulk of the Visigoths, the powerful Tervingi, under the leadership of Fritigern and Alavivus, sought refuge within the confines of the Roman Empire and trekked toward the Danube border, where they appeared in 376.

So it was that the Roman Empire suddenly found itself faced with upward of 50,000 barbarians in desperate need of food and land. The obvious danger was that a refusal of the Tervingi pleas would result in war. The issue demanded the personal attention of the Eastern Emperor Valens, who had successfully dealt with the Goths a decade previous. Unfortunately for the Romans, Valens was over 300 miles to the south, at Antioch, and involved in a war against the Persians.

To deal with barbarian invasions and with the more organized Persians, the Roman emperors of the late fourth century had at their disposal an army in excess of half a million men. However, the Empire’s borders were vast and the bulk of the troops were in stationary garrisons, the limitanei. Only a third were in the better trained and armed mobile army, the comitatenses. Virtually none of the soldiers and few of the generals were Romans, the soldiers being recruited from the Balkan Peninsula, Asia Minor, Gaul, and the African frontiers, or from beyond the Rhine and Danube. Indeed, contingents of Goth troops served within the ranks of the eastern army. The barbarian ethnic origins of the Roman troops increased their fighting prowess but at the same time undermined their reliability and loyalty.

Defiantly, the Goths Refused to be Disarmed

In the east, the bulk of the mobile army was deployed against Persia. The immediate defense of the lower Danube would have to be carried out by the barely adequate Thracian garrison. After much heated debate among ministers and councilors, the pleas of the Tervingi were accepted on the condition that their warriors be disarmed. Without their weapons the Goths would pose little threat and present a handy source of recruits for the legions.

Late in 376 the Tervingi received news of their acceptance. As a gesture of goodwill to the Romans, Fritigern and his people accepted the religion of the Emperor, that of Arianism, a creed of Christianity that believed Jesus the Son to be mortal and separate from, not co-eternal with, God the Father. In spite of such a show of friendship, the Tervingi prudently refused to obey the Roman demands of disarmament and defiantly kept their weapons.

The Tervingi crossed the Danube on boats and rafts made up of tree trunks. Heavy rains had swollen the river and not a few Goths drowned in its ice-cold torrents. The barbarians camped on the southern bank of the river near Durostorum (Silistria) where they endured a bitter winter. Not only were Roman food supplies barely adequate, but the corrupt Roman Count of Thrace, Lupicinus, used the supplies destined for the Goths to run a black market. The barbarians were reduced to starvation and forced to barter the favors of their women and sell their children into slavery in return for dog meat dished out by the Romans.

Around this time a tribe of Ostrogoths, the Greuthungi, appeared on the Danube border. Under their leaders, Alatheus and Saphrax, the Greuthungi managed to avoid Hunnish subjugation. Like the Tervingi, they wished to cross into the Empire. The Romans rejected their request. The Tervingi, after all, had been former federates, but the Greuthungi were an unknown factor. Roman troops deployed along the Danube as river patrols forced the Greuthungi to remain on the river’s north bank, but this was soon to change.

Waking What They Wanted

Early in 377, back at the Tervingi camp, tensions ran high and there were murmurs of revolt. To intimidate the angry barbarians, Lupicinus assembled the Roman Danube garrisons and shepherded the whole tribe toward his headquarters at Marcianople. There he might keep a better eye on them, even rid himself of potentially rebellious chieftains. But with the Danube defenses stripped of their troops, the way became clear for the Greuthungi, who forded the river and followed in the Tervingi’s wake.

At Marcianople, Lupicinus invited Fritigern and Alavivus to a dinner conference. While the chiefs’ honor guard remained outside the palace, Fritigern and Alavivus pleaded their case to Lupicinus. Of the two, Alavivus was probably the most vocal. Meanwhile, outside of the city, Roman soldiers kept the hungry Tervingi multitude away from the city’s walls. The barbarians soon turned unruly. The Romans tried to quiet them by dragging away troublesome individuals. But such bullying only inflamed the Tervingi more and some of them picked fights with the Roman soldiers.

Inside the palace, Lupicinus seemed drowsy after a luxurious meal followed by a noisy floorshow. Yet when he heard of the troubles outside the city, he suddenly ordered the Tervingi chiefs’ guard of honor to be put to death and for Alavivus to be seized and held captive. The situation looked equally dire for Fritigern but he cleverly wormed his way out of the predicament. Perhaps not too dismayed at having been rid of his rival, he promised Lupicinus to prevent bloodshed if released. It was a ruse. With swords drawn, Fritigern and his personal retainers made their way through the palace and angry crowds gathered in the city. Alavivus was never heard of again.

Once back with his people, Fritigern promptly struck out to loot the countryside. No longer would he heed the will of the Romans, no longer would they suffer hunger and slavery. From now on the Goths would take what they wanted and make war on those who opposed them. The mournful blare of the barbarian battle horns—of the wild bull, the Uri—resounded across the countryside.

In answer Lupicinus mustered his troops and met the Goths nine miles outside Marcianople. The Roman troops fought bravely but the onslaught of the Goths proved unstoppable. Leaving his troops to be slain among their fallen standards, cowardly Lupicinus rode away to hide behind Marcianople’s walls.

The Tervingi warriors equipped themselves with the arms and armor of the slain Roman soldiers. Soon after, they joined up with the Greuthungi. Their combined forces raided all the way to Adrianople. Outside the city, Fritigern found yet more allies. In light of recent events, the city populace had turned on a regiment of Goths that had formerly been part of Adrianople’s garrison. Surrounded by a clamorous multitude, which pelted the Goths with missiles, the barbarians beat their way out of their encampment in the city suburbs with their blades.

The newcomers enthusiastically joined Fritigern who led their combined forces in an assault against Adrianople’s walls. But the Goths lacked knowledge of siegecraft and the city’s defenders were well armed; Adrianople was a locale of fabricae, Imperial armament factories. The barbarians suffered heavy casualties with no gain. Fritigern counseled from now on “to keep peace with walls.”

“Everything Was Consumed in an Orgy of Killing and Burning…”

Instead the Goths broke up into smaller bands to plunder the Thracian countryside. Escaped slaves, primarily mine workers, drifted in to join Fritigern’s army. Numerous Goth children, whom the Romans had dragged into slavery, were restored to the joyful embrace of their parents. Upon the Roman civilian population the barbarians exacted brutal vengeance. “Everything was consumed in an orgy of killing and burning that paid no regard to age or sex,” wrote Ammianus Marcellinus, the fourth-century Greek historian and principal source for the Goth wars.

To restore order, strong detachments of Roman troops from Armenia arrived in Thrace. Word also reached Flavius Gratian, the 18-year-old West Roman Emperor and nephew of Valens, who sent regiments from Pannonia and Gaul led by Count Richomer the Frank. But even before the western reinforcements arrived, the Armenians managed to drive large numbers of barbarians into the defiles of the Haemus Mountains and push Fritigern’s main army into the marshy region of the northern Dobrudja near the town of Salices.

With his back to the Danube and the shore of the Black Sea, Fritigern decided to make his stand. The Goths drew up a laager (a circle of wagons) and went on the defensive. Not wishing to risk an attack on the Goth wagon fortress, the Romans planned to wait until hunger forced the Goths to break camp. To the frustration of the Romans, Fritigern got word of the enemy plan through a deserter and stoutly remained inside his wagon fortress. To bolster his forces, Fritigern called in all nearby raiding parties.

In late summer 377 Fritigern decided to press the attack against the inferior Roman forces. The Romans were ready and the two sides met at the crack of dawn in Ad Salices, “the battle of the Willows.” The Romans’ barbarian troops began the attack with the “Barritus,” the battle song that began softly and then worked its way up to a deafening roar. The Goths responded with a thunderous chant in praise of their forefathers.

A hail of javelins, sling-shot, and arrows at long range descended on both sides, which advanced behind the barrier of shield walls. The infantry lines clashed while Goth and Roman cavalry skirmished along the flanks, chopping down loose infantry units and stragglers. With huge fire-hardened clubs the Goths threatened to cave in the Roman left wing. A fierce counterattack by Roman reserves restored the situation. Both Roman and Goth fought with unrelenting tenacity but neither could win the upper hand. At nightfall each army crept away to lick its wounds. Flocks of ravens and other carrion feeders descended upon the battlefield, which years later remained covered with the bones of the fallen.

Barbarian Hordes Pillaged with Impunity

The Romans fell back to their blockade and a lull set in. Richomer returned to the west to obtain further troops and orders from Gratian. The remaining Roman forces set up a system of outposts and pickets to maintain the blockade, which dragged on into November.

Once again the Goths faced starvation. Their future looked bleak, but Fritigern, with promises of booty, managed to entice Alani and Hunnish bands to cross into the Empire and join his Goth army. The newcomers tipped the balance of power and caused the Romans, who feared an imminent breach of their thin lines, to order a general withdrawal.

Hordes of barbarians now pillaged throughout Thrace. At Dibaltum the Romans suffered yet another defeat when a large troop of retreating Roman infantry was ambushed and annihilated by Goth cavalry. Emperor Valens received the news of the recent disasters while still at Antioch. He hastily concluded a peace with Persia. With the extra troops now available he left for Constantinople in 378 to personally take the field against the Goths.

When Valens arrived at Constantinople on May 30 he was dismayed to find the public in a state of unrest over his disastrous Goth policy. Brutal and sadistic, the pot-bellied and bow-legged emperor had never been popular with the people who suffered through his purges of torture, public execution, and banishment that followed the civil war of the previous decade. It also did not help matters that he was of the increasingly detested Arian faith.

To avoid the crowds, Valens stayed in his capital only a few days before he moved his headquarters to the nearby village of Melanthias. He decided to replace the commander of his infantry, Trajanus, with Sebastianus, an able general who had personally requested his recent transfer to Constantinople. Trajanus, nevertheless, remained in the emperor’s service.

At Melanthias, Valens attempted to boost the morale of his soldiers with pay, supplies, and flattery. The perhaps 20,000-man army then slowly marched toward Nice. Sebastianus and an elite corps of two thousand lightly armed soldiers were sent ahead to conduct guerrilla warfare against the barbarians.

Sometime in June, scouts brought the news of a large number of barbarians near Adrianople. The barbarians, heavily laden with booty, had returned from a devastating raid into the foothills of the Rhodope Mountains and were pulling back farther to the main Goth camp between Beroea and Nicopolis. Sebastianus set out in pursuit. Along the shores of the river Hebrus, he fell upon the Goths in a night ambush and killed all but a few.

More good news for the Romans was on the way with the arrival of a letter from West Roman Emperor Gratian. Gratian recently beat back serious Alemanni (West German) incursions over the Rhine and was coming to aid his uncle with the Goths. Encouraged by Sebastianus’s victory and Gratian’s forthcoming reinforcements, Valens marched forth from Nice to Adrianople, arriving at the city in mid-July.

At Adrianople, Valens received Richomer returning from the west with more news from Gratian, who beseeched his uncle to wait for his arrival and not to do anything rash. Information also came in from his scouts, who told Valens of Goth cavalry activity to his rear, threatening to sever the supply line to Constantinople. Valens sent a regiment of infantry and archers to secure the roads to his capital and entrenched his army in front of Adrianople, within a strong rampart and moat, to await his nephew. An eventual Roman victory seemed assured but for Valens, who smoldered with jealousy over his popular young nephew’s recent victory. Valens resented having to be bailed out by Gratian and wished that he alone could claim the victory laurels.

Barbarians at the Gates of Rome

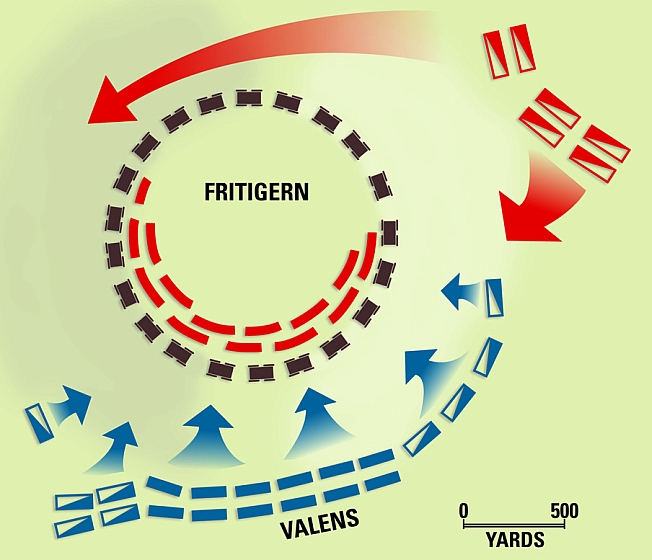

On the Goth side, Fritigern was faced with the dual problems of having to prevent the union of the Roman armies and luring Valens into battle before Gratian’s arrival—his Goth army was too weak to risk an attack on the fortified Roman encampment. Fortunately for Fritigern, Gratian was delayed by Alan raiders at Casta Martis, in eastern Dacia, who may have been acting in concert with the Goth leader. Fritigern then gathered his various foraging parties to prevent them from being destroyed piecemeal by Sebastianus, and marched to Cabyle. From there he descended toward Adrianople. Circumventing the city, he struck toward Nice to position himself between Constantinople and Valens’ army.

Roman scouts reported that the Goth army was a bare 15 miles from Adrianople, advancing toward Nice, and numbered a mere 10,000. Such tidings further strengthened Valens’ resolve to engage them on his own. After all, with a two-to-one numerical superiority, Valens could scarcely stand idly by with the main Goth army poised to ravage the countryside all the way to the gates of his capital.

A council of war was held. Victor the Sarmatian, a cavalry commander and veteran of Valens’ earlier Goth war, spoke for many of the generals who urged Valens to wait for Gratian. In contrast, Sebastianus, roused by his own success, counseled an immediate attack in what he saw as an assured victory.

At this point an Arian priest, sent by Fritigern, arrived at the Roman camp. The priest declared that the Goths were willing to accept peace if the province of Thrace, along with all its livestock and grain, was ceded to them. He also slipped Valens a secret note from Fritigern. The note asked the emperor to move out with his army to overawe Fritigern’s unruly barbarians into accepting a peace.

Valens Aims to Crush the Goths Once and for All!

No doubt the Goth’s desire for Thrace was sincere. But their belief that the emperor would simply give it to them seemed incredibly naïve to the point of being a coverup for luring the Romans into battle. Not surprisingly Valens rejected the “peace” proposal. A decade previous Valens had defeated the Goths; he was sure he could do so again. On the morning of August 9 Valens led his army from Adrianople to crush the Goths once and for all!

The sun beat down mercilessly, with temperatures of up to 100 degrees Fahrenheit, on the Roman soldiers who force-marched 12 miles over rough ground to Fritigern’s camp. Cavalry led the front of the column and brought up the rear, with the infantry in the middle. The infantry made up about two-thirds of the army; it consisted of a thousand men: heavily armed legions and smaller units of more versatile auxilia. Around two in the afternoon, before having their midday meal, the tired and hungry Romans unexpectedly stumbled upon the Goths. They were encamped on a hill, as usual, within their wagon burg.

Overconfident, Valens had ordered inadequate reconnaissance. The Romans were caught off guard and still strung out along the road. With much confusion and delay, barbarian howls, and a clash of shields, the Roman soldiers began to form their lines of battle. The lead cavalry took position on the right, the infantry eventually formed the center, and the rear cavalry charged ahead and attempted to form the left wing. A corps of Batavi, a Frankish tribe renowned for its cavalry, remained behind as a reserve. To make things even more difficult for the Romans, the Goths lit fires on the plain between the two armies. The heat and smoke became all but unbearable to the Romans while the Goths were able to seek shelter beneath the cool shade of their wagons.

Nevertheless, like the Romans, the Goths proved unprepared for battle. Fritigern’s entire cavalry, under Alatheus and Saphrax, were out foraging, so that only the Goth infantry defended the camp. At once Fritigern summoned Alatheus and Saphrax back. To buy time until their arrival he dispatched more envoys to the Romans. These were men of humble origins and at first were scorned by the emperor. The last brought an appeal from Fritigern who pleaded that, in return for noble Roman hostages, he would do all in his power to secure a peace. Valens accepted Fritigern’s dubious proposal. Either he, too, wished to buy time to properly deploy his troops, or the fortified position of the enemy and the exhausted state of his own men caused him to reconsider not waiting for Gratian.

The Goth Army Strikes Like a Thunderbolt From the Mountains

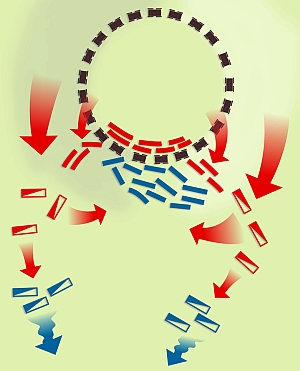

Brave Richomer volunteered to be the hostage but he never reached the Goth camp. On his way to the Goths, his overeager bodyguard of archers and skirmishers lost their nerve and prematurely opened fire. A limited Goth counterattack threw the skirmishers back against their own lines in confusion. Valens decided to order a general advance. The Roman infantry was still not fully deployed but the cavalry was ready. At this moment the cavalry of Alatheus and Saphrax appeared on both flanks of the Goth laager. The Greuthungi chiefs wasted no time and led the five thousand or so Goth, Alan, and Hun horsemen in a wild charge down the hillside.

Brave Richomer volunteered to be the hostage but he never reached the Goth camp. On his way to the Goths, his overeager bodyguard of archers and skirmishers lost their nerve and prematurely opened fire. A limited Goth counterattack threw the skirmishers back against their own lines in confusion. Valens decided to order a general advance. The Roman infantry was still not fully deployed but the cavalry was ready. At this moment the cavalry of Alatheus and Saphrax appeared on both flanks of the Goth laager. The Greuthungi chiefs wasted no time and led the five thousand or so Goth, Alan, and Hun horsemen in a wild charge down the hillside.

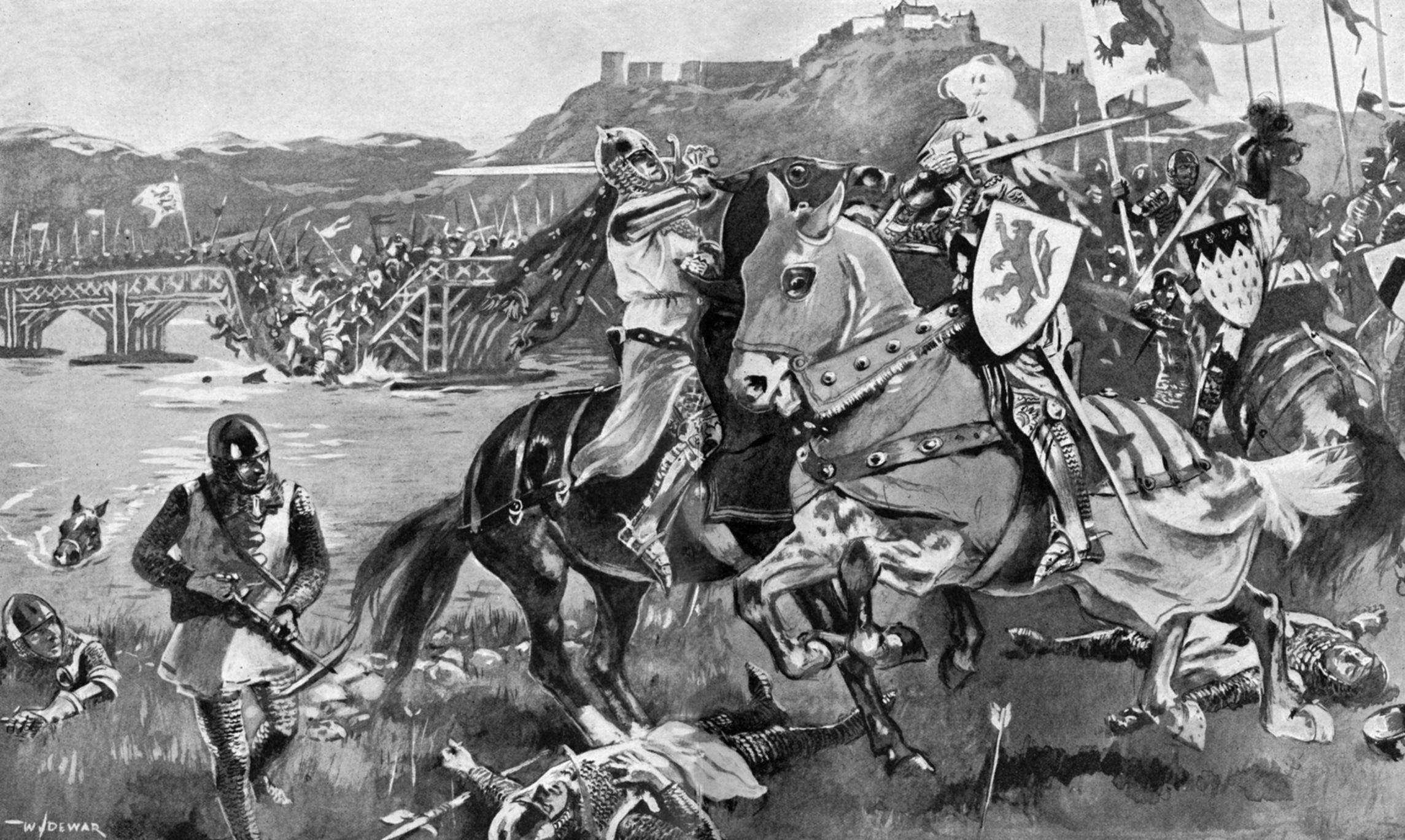

The Goth cavalry hit the Roman cavalry, in Ammianus’s words, “like a thunderbolt from the mountains.” The Roman right wing cavalry was closing in on the Gothic camp when it was completely overwhelmed and scattered by the furious charge of the barbarians. The cavalry on the Roman left wing fared even worse. Having advanced too fast it opened a dangerous gap between it and the Roman infantry. Into this gap rode the Goth cavalry to strike the Roman cavalry from the sides and rear. Hewn to pieces, the Roman horsemen were swept from the field or driven back upon their infantry.

With the Roman cavalry eliminated, Alatheus and Saphrax’s horsemen galloped around the Roman infantry’s flanks and rear. Caught between the hammer of the enemy cavalry and the anvil of the wagon ramparts, the Roman soldiers were pressed together amid much confusion. Vast clouds of dust all but obscured a sky thick with the arrows of Goth archers.

Like an avalanche the Goth infantry now broke loose from behind the wagon barricades and stormed upon the legions. Surrounded and crowded, many a Roman soldier had scarce room to draw back his sword arm. But the men who fought for Rome were barbarians themselves—warriors who refused to give up without a fight. Ammianus captured the savageness of the battle:

“Strokes of Axes Split Helmet and Breastplate”

“The lines dashed together like beaked ships and tossed about like waves at seas. On both sides strokes of axes split helmet and breastplate. One might see a barbarian filled with lofty courage, his cheeks contracted in a hiss, hamstrung or with right hand severed, or pierced through the side, on the very verge of death threateningly casting about his fierce glance. The infantry, their lances broke, content to fight with drawn swords, plunged into the dense masses of the foe, regardless of their lives.”

“The lines dashed together like beaked ships and tossed about like waves at seas. On both sides strokes of axes split helmet and breastplate. One might see a barbarian filled with lofty courage, his cheeks contracted in a hiss, hamstrung or with right hand severed, or pierced through the side, on the very verge of death threateningly casting about his fierce glance. The infantry, their lances broke, content to fight with drawn swords, plunged into the dense masses of the foe, regardless of their lives.”

The battle continued until sunset, when what remained of the Roman lines finally broke under the pressure. Valens himself stood among a battalion of elite Palatini troops, the lancearii and mattiarii who thus far had held back the enemy. Trajanus, who was with the emperor, cried out that all hope was lost unless the Batavi reserves came to the rescue. Upon hearing Trajanus’s words, General Victor hastened to find the Batavi only to find that they had already taken to flight. Everywhere the Goths, berserk with rage, hacked down fleeing Imperial infantry with their double-edged long swords or impaled them on their spears, whether they surrendered or not. Victor decided to make good his escape while he could.

Behind Victor the Palatini finally gave way to the Goths. With all but his personal bodyguard bolting in panic, Valens too attempted to flee but was mortally wounded by an arrow. Dragged to a nearby peasant’s cottage by his entourage, his bodyguard fought another small unit action against the Goths. Without knowing that the emperor himself was inside the building, the Goths set it aflame, burning everyone inside. Thus ended Valens’ 14-year reign. To the Catholic Christians of the day, it seemed that the fires of Hell had claimed the hated “Arian” Valens.

The emperor did not die alone. Beneath a dark, moonless night, the blood-drenched battlefield was covered with heaps of the 14,000 dead Roman soldiers, virtually the entire Roman infantry. Along with Victor, Richomer managed to flee the slaughter but they were the exception. Trajanus, Sebastianus, the Masters of the Stables and of the Palace, and 35 tribunes were killed. Of the Gothic losses there are no records, but considering the length of the battle they too must have been heavy.

A Bane for Rome, a Boon for the Goths

Adrianople was one of the greatest military disasters in Roman history, later heralded as the beginning of the end for the Roman Empire. Its immediate consequences, however, were negligible. The Goths, now splendidly equipped with Roman arms and armor, marched on to Adrianople where they hoped to capture Valens’ war treasury and supplies.

The second Goth siege of Adrianople began with preliminary and confused engagements in the suburbs on August 10. A thunderstorm dispersed the attacking army. Fritigern, who wisely remembered his earlier inability to capture the city, opposed a direct assault in favor of deserters within the city who were willing to open the gates to the Goths. When this plan failed the other Goth chiefs overruled Fritigern’s caution, and on the 12th the Goths fervently stormed the walls.

Accompanied by the drone of war horns, the chiefs led the assault. The city was jammed to the limit with war refugees from the defeated Roman army, who ably manned heavy catapults and other missile weapons in the city’s defense. With many of their men skewered by the javelins or crushed beneath the monstrous rocks of siege engines, the Goths failed to make any headway. Both below the walls and on the parapets, dead Goths and Romans lay in heaps.

Frustrated, the Goths decided to move toward Constantinople. Only when they got there did they seem to realize the utter inadequacy of their army in face of the Roman capital’s lofty fortifications. After being given a bloody nose by a sortie of Arab horsemen, the Goths abandoned any hope of taking Constantinople. This deprived Fritigern of the much-needed supplies to keep his army unified. Once again his army splintered into various small factions that preyed upon the hapless Thracian rural population.

Gratian realized that the disaster of Adrianople meant a lengthy and drawn-out campaign against the Goths—a campaign that he, with his commitments in the west, would not be able to carry out. Accordingly, in January of 379 he raised Theodosius the Spaniard, a veteran commander of the Illyrian cavalry, to be Emperor of the East.

Rome Pays a High Cost for Peace

During the next three years Theodosius had his hands full. In 380 Fritigern and the Tervingi raided as far as Thessaly where they inflicted a defeat on Theodosius. Meanwhile, Alatheus and Saphrax led the Greuthungi, Alans, and Huns into northern Illyricum but suffered a loss to Gratian’s army. The following year, small-scale actions against scattered Goth raiders drove both bands back into Thrace.

During the next three years Theodosius had his hands full. In 380 Fritigern and the Tervingi raided as far as Thessaly where they inflicted a defeat on Theodosius. Meanwhile, Alatheus and Saphrax led the Greuthungi, Alans, and Huns into northern Illyricum but suffered a loss to Gratian’s army. The following year, small-scale actions against scattered Goth raiders drove both bands back into Thrace.

By 382 Fritigern had disappeared from the scene, due to death or because he lost the support of his followers. After years of wandering around the Balkans and continuous minor skirmishes, the Goths had become weary of battle and were ready for a peaceful resolution. Theodosius was ready to give them one.

The Greuthungi, Alans, and Huns were settled in Pannonia II and the Tervingi in Moesia II, the same region originally granted by Valens. However, under Theodosius both groups became federates of the Empire, were not required to pay tribute, and received high pensions in return for their military services. Vast numbers of Goths were also enrolled into the Imperial army, again at extraordinary salaries. Theodosius became “the friend of peace and the Gothic people.”

For the Romans peace finally reigned throughout the land, albeit at a high monetary cost and with potentially dangerous high numbers of Germans in the army. As to the Huns, the original cause of the whole war, their migration toward the west petered out, as for now they consolidated their rule over the Ostrogoths and the former Visigoth lands of Old Dacia.

The Beginning of Rome’s End?

The battle of Adrianople has traditionally been seen as the deathblow to the legions and the advent of a thousand-year supremacy of cavalry on the battlefield. The Gothic victory is often described as one of heavy cavalry over infantry. True, after they routed the Roman cavalry, the Goth horsemen ensured the encirclement of the legions. But the ratio of cavalry units on both sides was roughly equal, with infantry comprising the bulk of both forces. The reason for the Roman defeat was not so much a lack of cavalry, but poor leadership and exhausted and disorganized troops having to fight a fresh and better-led enemy.

The battle of Adrianople has traditionally been seen as the deathblow to the legions and the advent of a thousand-year supremacy of cavalry on the battlefield. The Gothic victory is often described as one of heavy cavalry over infantry. True, after they routed the Roman cavalry, the Goth horsemen ensured the encirclement of the legions. But the ratio of cavalry units on both sides was roughly equal, with infantry comprising the bulk of both forces. The reason for the Roman defeat was not so much a lack of cavalry, but poor leadership and exhausted and disorganized troops having to fight a fresh and better-led enemy.

As to the advantage of cavalry over infantry, this was nothing new. Although for a long time the Roman army, to its detriment, continued to lack an adequate cavalry arm, the increasing strain put on the Roman army by mounted barbarians and Persian Sassanids in the third century caused the Emperors Diocletian and Constantine to raise the prevalence of the cavalry. Even the Praetorian Guard was disbanded, to be replaced by a new guard, the scholae palantinae, made up of barbarian cavalry. Thus Adrianople was less a turning point than part of an ongoing trend in which Rome’s enemies were increasingly mounted and Rome’s armies had to follow suit. By the fifth century this trend led to the cavalry replacing the legions as the primary unit of the Roman army.

The real importance of Valens’ defeat lay in the eventual peace settlement that occurred in the battle’s aftermath. For the first time, whole tribes of armed barbarians were settled within the borders of the Empire. This marked a new and ultimately disastrous stage in Roman-German relations. With whole regions given over to the rule of barbarian tribes, it was only a matter of time before these tribes declared total independence from Rome and thereby threatened to dismember the Empire from within.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments