By Peter Kross

The American Revolution was a proving ground for American spy operations. General George Washington’s use of deception, covert activities, secret inks, and informers was a model for future spymasters.

Washington’s idea that with good intelligence a smaller force could defeat a larger one was a notion that was subsequently proven on the battlefield. Without the splendid espionage network begun by Washington, the tide of battle and the future shape of the United States might have been different.

Legend has it that George Washington never told a lie. The fact is that he told plenty of them in furthering the American cause against Britain. Washington was America’s first grand spymaster, using all the tricks of covert warfare he had learned while serving as a commander in the French and Indian War. He deceived the British on numerous occasions and ran one of the largest espionage operations in American history up to the 20th century.

Badly outnumbered by the well-trained British Army—one of the most efficient fighting forces in the world—Washington decided to use every means available to counteract his formidable foe. He realized that not only could American secret agents gather vital information on the disposition of the superior British forces, but they could give the enemy false information as well.

A Massive 11% of the Military Budget Allotted to Intelligence Ops

During the Revolution, Washington used both civilians and soldiers for intelligence gathering. But the use of spies did not come cheap and it is estimated that Washington asked Congress for $20,000 for intelligence schemes, a whopping 11 percent of the military budget—and it was eventually supplied. Washington knew that money was the backbone of any successful intelligence operation. Later, when he became president, he had Congress pass a law called “the contingent fund of foreign intercourse,” or secret fund, with $40,000 allocated to that purpose. His successors in the White House, especially Thomas Jefferson, would use this “contingent fund” to carry out secret operations.

In 1778, Washington’s main opponent was British General Sir Henry Clinton, commander of all British military forces in the colonies. By June of that year, Clinton’s troops had taken control of New York City, with Washington’s troops making their stand in nearby New Jersey and Connecticut. In order to find out what Clinton’s intentions were, Washington ordered a major intelligence operation against the British, especially in and around their base of operations in Manhattan. The man he chose for that mission was Major Benjamin Tallmadge of Long Island. The group that Tallmadge formed was called the “Culper Ring,” a collection of patriots from Long Island who became Washington’s eyes and ears in New York.

Benjamin Tallmadge was born on February 25, 1754. His father was a minister in the Setauket, Long Island, Presbyterian Church in Suffolk Country. It was there that young Benjamin got his education. One of his boyhood friends, Abraham Woodhull, would in time join Benjamin as one of the principal spies in the Culper Ring (another name for the organization was the “Setauket Spies”). Tallmadge was also a close friend and schoolmate of Nathan Hale at Yale University. Tallmadge graduated from Yale in 1773 and taught school in Connecticut.

When the Revolution began, Tallmadge joined the Continental Army and in 1776 was made first lieutenant under the command of Colonel John Chester Wadsworth’s Connecticut Brigade. He fought in the Battles of Long Island and White Plains. He rose to captain and served with the 2nd Continental Light Dragoon Regiment (also called Sheldon’s Horse). Eventually he became a major and was given a job with Brig. Gen. Charles Scott, who served as the chief intelligence officer to General Washington. Washington saw promise in Tallmadge’s abilities and soon ordered him to patrol the so-called “neutral ground” in Westchester County, NY, between the Continental and British Armies. In time, Washington made Tallmadge his chief of intelligence for the Continental Army. His instructions were to create from scratch an undercover organization that could penetrate the British lines in New York, learn as much about their movements as possible, and report all they learned.

Washington made one stipulation to Tallmadge. He—Washington—did not want to know the real identities of the people Tallmadge used; only Tallmadge was to know who these men were.

Tallmadge did not have to look far in order to get men for his secret force. He chose a number of personal friends from Long Island, all anti-British in their politics, men whom he could trust with his life. The first man he chose was his boyhood friend, Abraham Woodhull.

Code Names and Spy Rings

Abraham Woodhull was a Setauket farmer whose family had lived in the area since 1657 and knew the land well. Woodhull had the important job of being in charge of the daily operation of the spy ring. His code name was “Samuel Culper,” hence the name “Culper Ring.” Benjamin Tallmadge was known as “John Bolton.” Woodhull went on to choose Robert Townsend as his principal spy, and he was given the nickname “Culper Junior.”

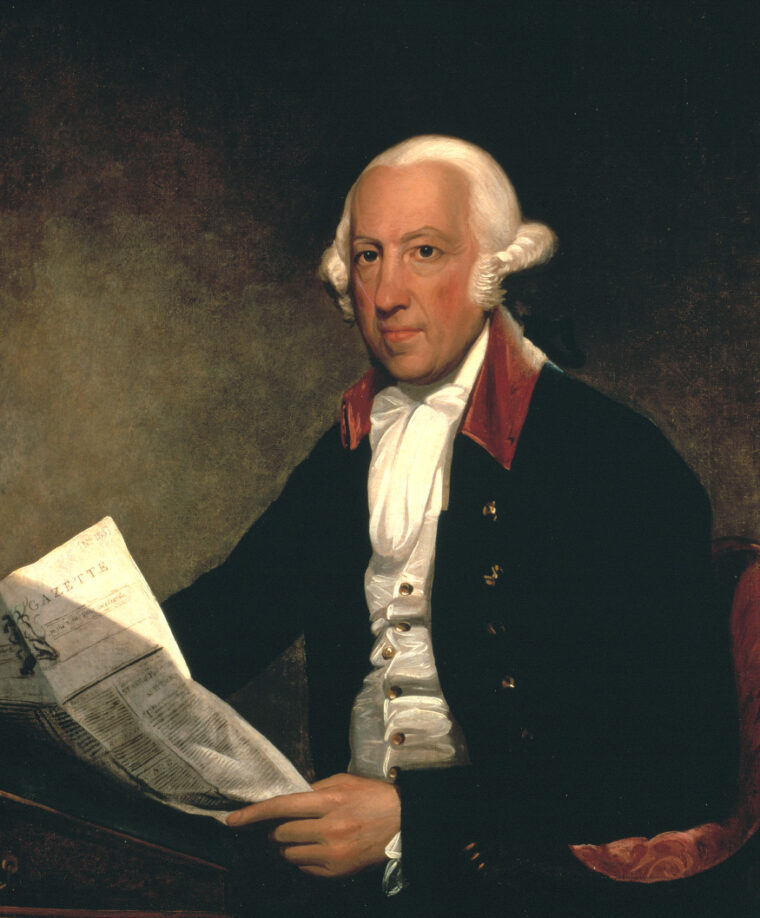

Robert Townsend was the main conduit of information in New York City. From 1778 to 1781, he would receive all news coming from his agents on Long Island and get the information to General Washington. Townsend’s father lived in Oyster Bay, NY, and he went back and forth from there to New York City, carrying intelligence gleaned from his contacts. Townsend also had another cover that he used brilliantly. He was an amateur writer and made friends with the powerful newspaperman and British sympathizer James Rivington, the publisher of the New York Gazette. Using his journalistic cover, Townsend befriended many British military officers and through casual talk, and a few drinks, was able to extract vital information that Washington badly needed. In a twist of fate, it turned out that the “Tory” James Rivington was all along one of Washington’s spies in New York.

Another man to join the group was Caleb Brewster, a soldier in the revolutionary army who had previously served in battle with Benjamin Tallmadge. Brewster was a lieutenant in the artillery corps and fought in Long Island and Connecticut. Brewster’s main job for the Culper Ring was to man a whaling boat in Long Island Sound, spying on the British mainly from the Connecticut shoreline, but also carrying intelligence across the sound from Connecticut to Long Island. As such he was the most important intermediary between General Washington and Major Tallmadge.

One other member of the secret group was 29-year-old tavern owner Austin Roe of East Setauket. Roe’s tavern was halfway between the end of Long Island and New York City and was a haven for travelers, both British and Colonial. Roe listened to his guests’ gossip and memorized the details. Using his hotel as a cover, Roe made numerous trips into British-held New York for the ostensible purpose of buying supplies. When he was in the city, he made covert contact with General Washington’s representatives and passed along whatever news he had learned from his sources.

Invisible Ink and Other Tricks

The information that Roe carried with him was secreted using invisible ink, a process that was also used by others in the Culper Ring. Roe would write his covert messages in invisible ink directly on regular communications, such as books or pamphlets. Only Roe and the recipient of the letter could decipher the secret part of the message. This ink, also called “white” or “synthetic” ink, was produced by Sir James Jay, a doctor who was the brother of John Jay, a prominent American patriot. In 1790, long after the War of Independence had been won, President George Washington paid a visit to Austin Roe’s tavern, meeting for the first time one of his principal secret agents.

The only female member of the Setauket Spies was Anna Smith Strong. She is supposed to have used her clothesline to notify Caleb Brewster when and where to position his whaleboat to receive confidential information. Her wet wash would be hung in a certain pattern, alerting Brewster that a plan of action was in the offing.

As an extra precaution, Tallmadge created a code or cipher system that substituted names and places with numbers. For example, Tallmadge was 721, Woodhull was 722, Townsend 723, and New York City was 727. Tallmadge had three code books made up and gave one to Washington. The material received from the Culper Ring went straight to Washington. But the commander-in-chief let his top military aide, Captain Alexander Hamilton, read the missives coming from Long Island. Hamilton did not know the real names of the Culper Ring, however, nor did he have access to all the intelligence they provided.

Throughout the war the Culpers were able to carry out their work in and around New York City under the noses of the British. They had an elaborate yet simple way of delivering their information to General Washington. Using a store he owned as the focal point of their plot, Robert Townsend would collect intelligence and wait for Austin Roe to come and retrieve it. On trips ostensibly to buy supplies for his family in East Setauket, Roe would go to the store. There he would give any information he had to Benjamin Tallmadge, who used a hiding place in the back of the store. Tallmadge would make comments, add his own material, and hand it back to Roe. Roe would then begin the 110-mile trek from New York City to Setauket, Long Island. From there, a number of strategically placed couriers would take the information across Long Island Sound to Connecticut, eventually winding up with George Washington and his aides.

Three episodes in particular proved the worth of the Culper Ring during the Revolution. In November 1779, they learned that the British had gotten hold of reams of paper identical to the type used for printing American money. The British planned to manufacture this currency and give it to their Tory sympathizers in Connecticut for paying their taxes. After the Culper Ring detected the operation they notified the colonial military commanders and warnings went out to look for bogus currency. Soon the British scheme was shut down.

The second major operation uncovered by the Culpers concerned the arrival of the French troops under the command of the Comte de Rochambeau. General Rochambeau’s troops were to arrive in Newport, RI, in force. The British commander in New York, Sir Henry Clinton, knew of Rochambeau’s planned landing in advance and would certainly consider an intervention. In order to deceive the British, Washington arranged for Clinton’s spies to intercept a message saying that the Americans were going to attack Clinton in New York once a detachment of British troops left to intercept Rochambeau’s forces in Newport. Believing this false information to be true, Clinton kept all his forces in New York and the huge French Army landed unopposed.

The Revolutionary War’s Best Kept Secret

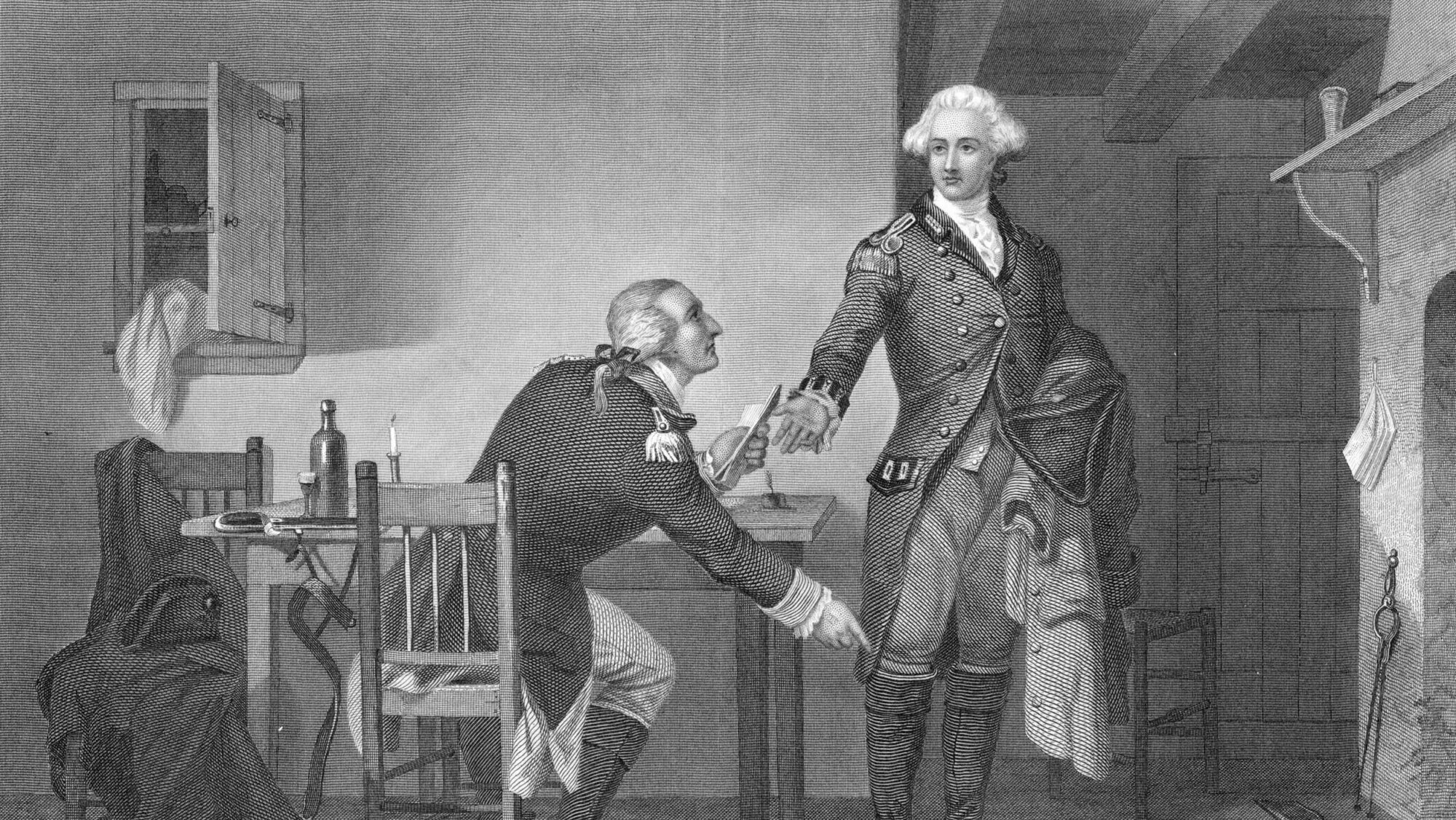

One of Washington’s worst intelligence failures concerned his friend of many years, Benedict Arnold. Arnold, a brigadier general in the American Army, became a British agent. It was the Culper Ring that first discovered that he was working for the enemy when British Major John André paid a visit to the home of Robert Townsend’s father in Oyster Bay, Long Island.

Townsend’s sister Sarah saw a stranger leave a note addressed to “John Anderson” and later heard André talking to another British officer about the fortifications at West Point, saying how easy it would be to capture the fort. Sarah told her brother about the mysterious man in their father’s home. Townsend quickly sent a message to Benjamin Tallmadge who found out that André-Anderson had been picked up with information about West Point stashed in his boot. Tallmadge remembered that Arnold had issued orders that André be allowed through the American lines. Townsend immediately sent word of Arnold’s treason to Washington’s headquarters.

Unfortunately, before Arnold could be captured, he fled to a waiting British warship and returned to British-occupied New York where he worked openly for the British. Washington planned a covert operation to capture Arnold and bring him back for trial, but before the plan could be carried out Arnold and his unit were sent to the Chesapeake Bay area. As for John André, he suffered the ultimate fate. After a short hearing by a number of American military officers, he was found guilty and hanged as a spy.

Fleeing the colonies, Arnold made his way to England in 1781 and eventually ended up in Canada. He later served in the British military in the West Indies in 1794-1795. He died in England on June 14, 1801, a man forgotten by his contemporaries.

After the war of independence was won, Tallmadge married Mary Floyd and moved to Litchfield, Conn., where he operated a prosperous dry goods store. He was elected to Congress in 1800 and served eight terms. He died in 1835, aged 81.

The Culper Ring adequately proved its worth during the Revolution and was one of the war’s best-kept secrets.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments