By O’Brien Browne

Orderly rows of Sumerian soldiers stretched across the grassy plain, their conical bronze helmets hard and bright under the sizzling sun. Hundreds of long, metal-tipped spears bristled from behind their rectangular shields of wood and hide. Their commander yelled out the order to advance and they tramped toward the enemy line, the arrayed troops of the Akkadian army.

Orderly rows of Sumerian soldiers stretched across the grassy plain, their conical bronze helmets hard and bright under the sizzling sun. Hundreds of long, metal-tipped spears bristled from behind their rectangular shields of wood and hide. Their commander yelled out the order to advance and they tramped toward the enemy line, the arrayed troops of the Akkadian army.

As they closed, there was a sudden movement in the Akkadian ranks and a whooshing noise as a black cloud arched through the air. It thudded into the Sumerian soldiers. They twisted, cried out, and crumpled to the ground, hit by a violent force that few had experienced before. Another volley of arrows aimed with unusual precision decimated their lines. Brandishing spears and sickle swords, the Akkadian troops now rushed forward as the Sumerian survivors broke and ran.

These ancient soldiers had been hit by the deadly fire of the preeminent weapon of the day, the composite bow. Sleek and graceful, accurate and powerful, a masterful combination of natural products and human ingenuity, the composite bow emerged from the kingdoms of ancient Mesopotamia to revolutionize war-making for millennia and bring about the rise and fall of empires.

Origins of the Composite Bow

The origins of this remarkable innovation have long been debated, with visual imagery providing the only proof. Recent research places its appearance at Mari, a mid-third millennium 2500 bc Early Dynastic city in what is now Syria. Somewhat later, a dramatic representation of the composite bow was carved on one of the most famous steles of the ancient world. It depicts the Akkadian king Naramsin, grandson of Sargon I, firmly grasping the bow in his right hand as he grinds his enemies into the dust, during the 2250 bc. The stele illustrates the world’s first instance of a living ruler proclaiming himself divine: Naramsin wears the horned helmet of a deified hero. Significantly, this new divinity’s weapon of choice was the composite bow.

Bows and arrows had of course been in use since prehistoric times, going back at least 40,000 years. Spanish caves have 10,000-year-old rock paintings that show pitched battles between combatants armed with bows. These simple or “self” bows (from the meaning of the word “being uniform throughout”) were made from a single stave of wood, strung with a string from which the arrow was propelled. Although uncomplicated, they were effective weapons, allowing men to fire at an animal or an enemy from a relatively safe distance.

At some point in the past, after decades or, more likely, centuries of experimentation, driven by the need to improve accuracy, power, and range to subdue their opponents or bring down game, clever and determined artisans developed the composite bow. Theirs was an immense technological advancement that would change the face of warfare in the East.

A Feat of Engineering

The name itself belies its construction. The basic structure consisted of a grip, two arms, and two tips, all of plain or laminated wood. These were bound together using a glue made by boiling down fish bones and cattle tendons. The slender strips of wood were then curved by steaming and slivers of animal horn were glued on the inner side, or “belly” of the bow. Then the bow was bent into a circle and animal sinew was glued on to the outer side, or the “back.” The horn section faced the archer and compressed when the bow was drawn; the animal tendon on the outside provided tension. The wooden part of the bow ended up being little more than a core, but of no less equal importance to the entire structure because it absorbed stress. As the bowman drew the string to shoot, all the various components of this engineering wonder smoothly came into play: the horn resisted compression, the sinew flexed, and the wood took the stress as the bow was made taut when drawn and then snapped back into shape upon release of the arrow.

The composite bow’s power and performance came not only from its unique design, but also from the correct application of the best materials available. Only special types of carefully selected sinew, wood, and horn were suitable for making composite bows. Illustrated in a document from Ugarit, a Bronze Age city, the epic hero Aqhat swears to provide the goddess Anat with the required materials:

“Let me vow ‘tqbm from Lebanon

Let me vow tendons from wild bulls

Let me vow horns from wild goats

Sinews from the locks of bulls.”

Another feat of engineering skill—and again the culmination of many prototypes and years of development—was to bend the tips of the bow to which the string was attached in the opposite direction of the draw, giving this highest development of the composite bow a distinctive “recurved” shape, dramatically increasing velocity and impact.

The composite bow was then left to cure for a year or more in storage rooms where humidity and temperature where highly regulated, allowing its various elements to meld into each other. If any of these procedures were not precisely followed, the bow would buckle or rip apart in the archer’s hands while being drawn. At the end of the curing period, the bows were tested and adjusted.

The manufacture of these weapons was time-consuming, labor-intensive, and expensive, requiring highly specialized training in the bowyers. “A great deal of art,” writes one researcher, “was involved in their preparation and application, much of it characterized by a mystical, semi-religious approach.” The bowyers passed their art and knowledge down to succeeding generations. The finished bow was a thing of great beauty, worth, and elegance, and each had its own “personality.” They were usually painted with intricate designs, stored in specially made protective cases, and only entrusted to the best archers.

The Challenge of Using a Composite Bow

Significant strength was required to string a composite bow. First millennium (668-630 bc) ancient Assyrian reliefs show two men involved in this process, although a strong man could do it alone. Great strength was needed to draw it as well, with the “weight” of the strung bow amounting to up to 150 pounds. Its ogival shape meant that the bow could be kept strung for a long time without fear of distortion. To protect bowmen’s arms and thumbs from the wicked snap of the string, they characteristically wore leather wrist protectors and thick thumb rings of bronze or some other metal. The enormous elastic properties of the composite bow gave it a vicious whip to drive an arrow with immense force, delivering a tremendous punch up to 400 yards. Its absolute range was roughly double this, being two to three times greater than the range of the self bow.

Ottoman chroniclers reported that Sultan Selim III fired an arrow 963 yards, a performance that has never been equaled by modern composite bows. The composite bow’s velocity was also much higher than that of simple bows and it could strike through armor at 100 yards. An additional advantage was that the composite bow’s arrows were of lighter construction, which meant that an archer could carry many more of them and thus remain in the field longer.

The ancients had discovered that the larger the size of a simple bow, the greater its pliability and range. Unfortunately, its very size made it unwieldy and virtually useless for firing from horseback or a chariot. The ogival design of the composite bow, however, reduced the distance between where the archer gripped the bow and how far he had to pull back the string. Further, because it was smaller—only 35 to 47 inches in length—it was ideally suited to be shot from chariots or horseback.

In all aspects, the composite bow was a vast improvement over the stave bow and the simple double-convex bow, an improvement on the stave that had more tension and firepower. It was also superior to that other famous missile weapon, the European long bow, which decided battles such as Poitiers and Crécy during the Middle Ages. Made of sap and heart woods and boasting admirable levels of force and elasticity, the long bow had two disadvantages: its large size, which meant it could only be wielded by archers on foot, and the weight of its arrow shafts, which restricted the number a man could carry. Another European invention, the crossbow, was powerful and accurate, but its heavy metal frame and cranking mechanism made it both slow to reload and impossible to fire from a galloping horse.

It was, however, perfect for shooting down from fortress ramparts on attacking troops. The composite bow—light, strong, and compact—had a higher velocity than these other types and outclassed them all.

Were These Bows the First Composite Tool of Mankind?

It is arguable that composite bows were the very first composite tools made by man and most likely the first to concentrate energy to propel an object forward with force. Virtually every design and production factor was the product of a well-developed civilization. The composite bow was a product of the city, or the city-state, although knowledge of its production techniques eventually spread to various tribal horse societies. Construction required a division of labor and skilled craftsmen, knowledge and use of advanced technologies, capital, learned expertise, and specific materials and methods. As far as is known, the first people to successfully wield composite bows in battle were the urban Akkadians, a people who ruled the world’s first empire from their capital city, Akkad, located in present-day Iraq. The rapid and far-ranging advances of the Akkadian army, which overran and subjugated the peoples and cities of Sumer, has been, in part, attributed to their skill with this highly advanced “super weapon.”

Like all great technological developments, the composite bow had spinoffs that were as profound as they were unforeseen. Because of the bow’s extraordinary striking power and range, armor had to be improved and worn more widely. Some scholars have even argued that the development of the mail coat—bronze scales sown onto a leather tunic—was brought about by the need to find a counter to this weapon. This in turn spurred advancements in metallurgy and related industries with concomitant ripple effects throughout early economies.

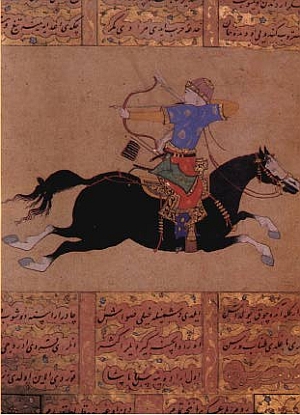

Moreover, weapon systems radically changed, for the composite bow was perfectly suited to be fired from the ultimate shock-weapon of the day, the chariot, which led to the chariot becoming a major wing of ancient armies, such as those of the Assyrians, Hittites, and Egyptians. From a speeding chariot, the composite bow was a rapid-firing missile delivery system capable of taking out combatants in a quick and deadly manner. As chariots came to be seen as too costly because of their materials and complex design, and too inefficient because of their two- or three-man crews, cavalry easily adopted the light, compact composite bow. In the hands of such fierce warriors as the Cimmerians, a little-known people from the steppes, and later the Mongols, this remarkable weapon helped make horse archery the most mobile, dynamic, and hard-hitting striking force of an army.

How the Bow Led to a Revolution in Military Tactics

Tactically, the introduction of the composite bow revolutionized warfare. With it, enemy troops could be fired upon before they came within javelin-throwing or simple bow range. For the first time an opponent could be taken by surprise and badly mauled before he came within range of his opponents. Once the composite bow was married to the chariot, armies were able to advance or retreat more rapidly, plunge deeper and more forcefully into the heart of enemy lands, and attack at the flanks or rear of conventional infantry while repelling other chariot forces.

Tactically, the introduction of the composite bow revolutionized warfare. With it, enemy troops could be fired upon before they came within javelin-throwing or simple bow range. For the first time an opponent could be taken by surprise and badly mauled before he came within range of his opponents. Once the composite bow was married to the chariot, armies were able to advance or retreat more rapidly, plunge deeper and more forcefully into the heart of enemy lands, and attack at the flanks or rear of conventional infantry while repelling other chariot forces.

Chariots with composite bows played a prominent role in the creation and fall of empires. In one of history’s epic encounters, the Battle of Kadesh (c. 1286 bc), 3,500 chariots led by Egyptian king Rameses II dashed against roughly the same number of Hittite chariots under the command of King Muwatalis, in what must have been a breathtaking display of archery and driving skill. Although the outcome of the battle produced no clear victor, the Egyptians, licking their wounds, recognized the Hittites as a power to be reckoned with. When these kingdoms waned, the Neo-Assyrian Empire arose, making good use of the composite bow with its huge chariot forces. When Neo-Assyrian chariots were phased out in favor of cheaper, more flexible cavalry troops, the composite bow remained the principle weapon. The Assyrians themselves were hard-pressed by the Medes, a people from the area now known as Iran, renowned as talented horseback riders and archers skilled with the composite bow. Eventually, the Assyrian Empire was partially destroyed by the Scythians, a mounted warrior nation from the steppes. They used a small composite bow measuring between 30 and 39 inches long, transported and protected in a case called a gorytos that could hold 75 bronze-tipped arrows. Despite differences in language, customs, and histories, all of these peoples, kingdoms, and empires shared one thing in common: the use of the composite bow as their definitive weapon.

The Persian Empire, stretching from North Africa to Afghanistan during its heyday at around 520 bc, was the largest empire the world had seen at that time. The Persian army possessed an elite unit, the “Immortals,” of 10,000 men armed with spears, swords, and composite bows. The fatal weakness of this impressive force, however, was that the archers carried no side arms, wore no helmets, and had no shields, relying on other foot soldiers to protect them with their own shields. Although they won many battles against the Greek city states, eventually even the mighty composite bow could not save the Persians when they came up against the heavily armored, well-trained phalanx regiments of the Greek armies.

Interestingly, the composite bow never found favor among the empires of the West. The Greek states, and later the Roman Empire, relied on the sword, the javelin, and well-armored, highly trained and disciplined troops to win victory on the battlefield. Archers armed with self-bows harassed their opponents, but the well-knit line or the crushing charge with spear, sword, and heavy shield was what won engagements for Greek and Roman commanders.

The Bow was a Favorite Weapon of the East

In the East, however, the composite bow reigned supreme. Indeed, a sturdy pony and a composite bow were the main weapons of the Mongol horse-fighters led by Genghis Khan and his successors, who conducted lightning-quick campaigns the scope of which have never been equaled. Genghis’s empire of mounted archers lasted from ad 1204 to 1405 and extended from China through Persia and Russia to Poland and East Prussia.

Mongol horsemen, like the Indian warriors of the American West, were experts in using their horses as living shields, shooting from under their necks or hunched low over their bobbing heads. The thundering hooves of their ponies and their fluid, extremely accurate archery skills made them the most formidable, dynamic, and terrifying fighters of the day. Instead of massed lines of infantry rushing and jabbing with spears or hacking with swords, the Mongols made rushes at their enemy, unleashed a rain of arrows, then pulled back to draw out enemy troops which were then cut off and eliminated. Once the main enemy force was disoriented, depleted, or panicked, the mounted warriors rushed back in, firing off their remaining arrows or swinging hand-held weapons to rout or destroy it.

The composite bow was developed and utilized with effect in Japan, Korea, China, and India as well as all of the kingdoms of the Near East. In the Americas it was used with devastating results by Great Plains Indian tribes both for war and hunting. The materials used in its construction varied according to local recourses—water buffalo tendon, for example, being favored by some Far Eastern cultures, while snapping turtle neck sinew was used by the Dakota Indians. In China, bamboo was employed not only as the core wood, but also on the “belly” and “back” of the bow.

Most archery experts agree that with the Ottoman recurved composite bow of the late 1700s and 1800s this weapon reached the epitome of its form and effectiveness. For strength and fire power, beauty of design and accuracy, plus the expert application of ancient craftsmen’s knowledge, Ottoman bows were the commanding weapon on the battlefields of Asia until the use of firearms became prevalent in the 19th century. It is noteworthy, however, that the basic accoutrements of the composite bow—the glues, sinew, and wood used in its construction, as well as the thumb ring, arrows, and quiver—had all remained basically unchanged since the middle of the third millennium 2500 bc.

Brandished by divine heroes, wielded by bronze-clad warriors in chariots, the decisive weapon on battlefields from Japan to North America, present at the creation of empires and instrumental in their ruin, the composite bow was arguably the most effective weapon in existence before the advent of the gun. Slim yet mighty, graceful yet deadly, it holds an exalted place as one of the greatest weapons in the history of warfare.

Really fascinating. Especially how far they could fire arrows compared to a “simple bow”.

A composite bow is expensive to make and requires training. A young boy need several bows, increasing in size, as he grows. Who provided the bows?.