By William E. Welsh

Along with five other Confederate generals of the Army of Tennessee, Maj. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne lost his life in the futile Confederate frontal assault at the Battle of Franklin fought November 30, 1864, in central Tennessee. The attack has been referred to as the “last grand charge of the war,” wrote James L. McDonough. To understand the reasons that General John Bell Hood hurled most of his 23,000 Confederates against the entrenched Union army of Maj. Gen. John Schofield, it’s necessary not only to look at the tactics of the time, but also at Hood’s peculiar personality.

The generals in the American Civil War who had attended military institutions had been taught the importance of using tactical flanking attacks and strategic turning movements to dislodge an enemy and inflict heavy losses on him. The frontal assault was called for if the enemy was disorganized, possessed greatly inferior numbers, and was not entrenched. The Union army had launched effective frontal attacks at Spotsylvania on May 12, 1864, and at Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1864. In those cases, the frontal attacks succeeded. But the armies at Franklin were equal in strength. What is more, the Yankees were well entrenched.

Far More Sinister Than Tactical Shortcomings…

But something far more sinister than tactical ineptness was evident at Franklin. Hood was furious when his subordinates failed to cut off Schofield’s retreating army at Spring Hill on November 29. Although the miscommunications that resulted in poorly executed, piecemeal attacks had enabled the Yankees to continue their strategic retreat north to rejoin Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland at Nashville. Hood seemed to blame everyone but himself. As the commander of the army, it ultimately was his responsibility to ensure that the attacks were launched in a timely and effective manner, which was something he failed to do.

During the march to Franklin in pursuit of the Federals, Hood resolved that to restore discipline in his officers and to instill a sense of esprit-de-corps in the rank and file it would be a good idea to launch a frontal attack against the Union position. In Hood’s mind, not only would this accomplish the goal of shattering Schofield’s force but also prove to his own soldiers that they were better fighters than their blue-uniformed opponents.

No Stranger to Bloody Gambles

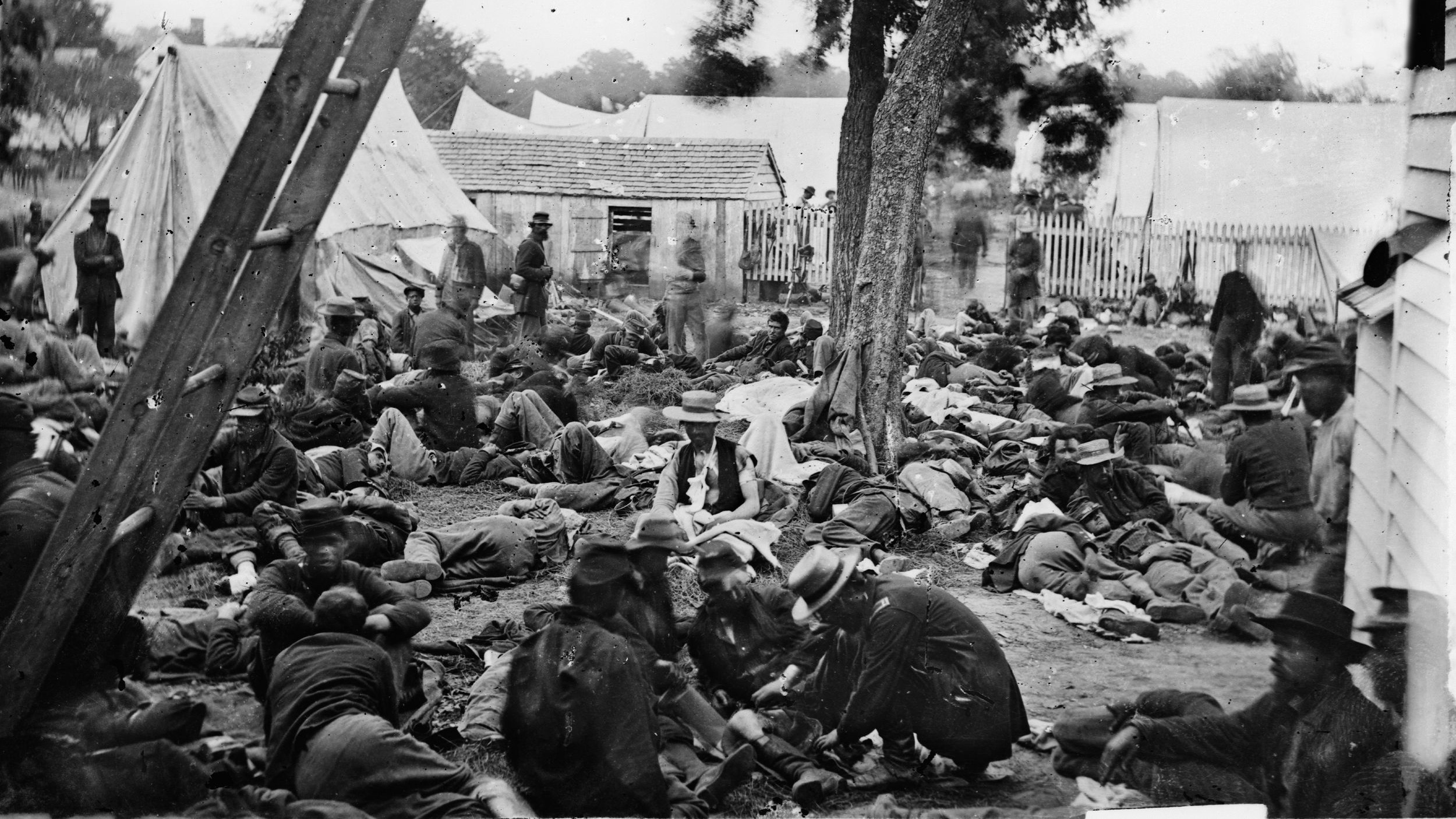

It was a foolhardy decision. He had shown in the fighting at Atlanta that he would gladly spend the blood of his men in a gamble to dislodge a Union army from its position. That nearly always meant that the Army of Tennessee would be bled heavily for an objective. Historians have noted that the Union position at Franklin was as strong as the Union center on Cemetery Ridge at Gettysburg. Indeed, Hood’s fatal charge at Franklin is akin to other futile headlong attacks, such as the Union attacks at Fredericksburg, Virginia, on December 13, 1862, and Cold Harbor, Virginia, on June 3, 1864.

What the Battle of Franklin revealed was that Hood did have the skills necessary to properly position his troops for a successful frontal assault. He wanted to smash the Union center but failed to properly mass his troops. Of the 18 brigades at hand as dusk approached, Hood positioned only seven to strike Schofield’s center.

To his credit, Maj. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne had advised Hood not to make the attack. Based on that incident, it’s easy to see who the better general was.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments