By Michael D. Greaney

On the morning of July 15, 1410 two heralds approached the enormous host of Poles, Bohemians, Hungarians, Czechs, Cossacks, Tartars, Livonians—any and all who felt they had a grudge against the opposing force of Teutonic Knights and their allies, also gathered from all over Europe. Returning from inspecting some of his Polish companies on the left wing, Jagiello, King of Poland and former Grand Duke of Lithuania, spied the two men approaching at a leisurely pace.

“Perhaps they are coming with a just peace,” remarked Jagiello with a degree of hope.

War Offered In Place Of Peace

“God grant it!” replied the priests around the King. The ranks of the Polish army opened to let the heralds pass, and they were soon before the allied commander. They bowed slightly—bowing deeper from horseback would have been impracticable as well as showing more honor than they felt their foe deserved.

“Grand Master Ulrich challenges Your Majesty and Duke Witold to mortal battle, and in order to rouse your courage, which seems to have failed, sends you these two naked swords.”

Dismounting, the heralds laid the weapons at the feet of the King.

Then they continued. “Grand Master Ulrich bids us also inform you that if the field of battle seems too small to you, he will withdraw his armies somewhat so that you need not loiter in the thickets.”

An Epic Battle By Any Other Name

Having hoped for a peaceful resolution to the conflict, Jagiello was taken aback by this arrogant display. Nevertheless, he rose to the occasion.

“Of swords we have enough,” he said, “but I will take these as an omen of victory sent me by God himself through your hands. The field of battle will be marked out by Him. And it is to His justice that I now appeal, making complaint of my wrong and your lawlessness and pride. Amen!”

In this fashion, more or less, Henryk Sienkiewicz described the opening of what one enthusiast called “the greatest battle in the history of the world” in Sienkiewicz’s climactic scenes of his eight hundred-page epic, The Teutonic Knights. Sienkiewicz, the most popular novelist in the world in the final decade of the 19th century, and almost a hundred years after his death still Poland’s best-selling author, described a scene that was the culmination of centuries of struggle and hardship on both sides. Confusingly, the battle was to be known to the Germans as Tannenberg, to the Poles as Grunwald or Grunfeld, and to the Lithuanians as Zalgiris. For clarity’s sake, we will refer to the battle as “Tannenberg.”

Origins Of The German “Iron Cross”

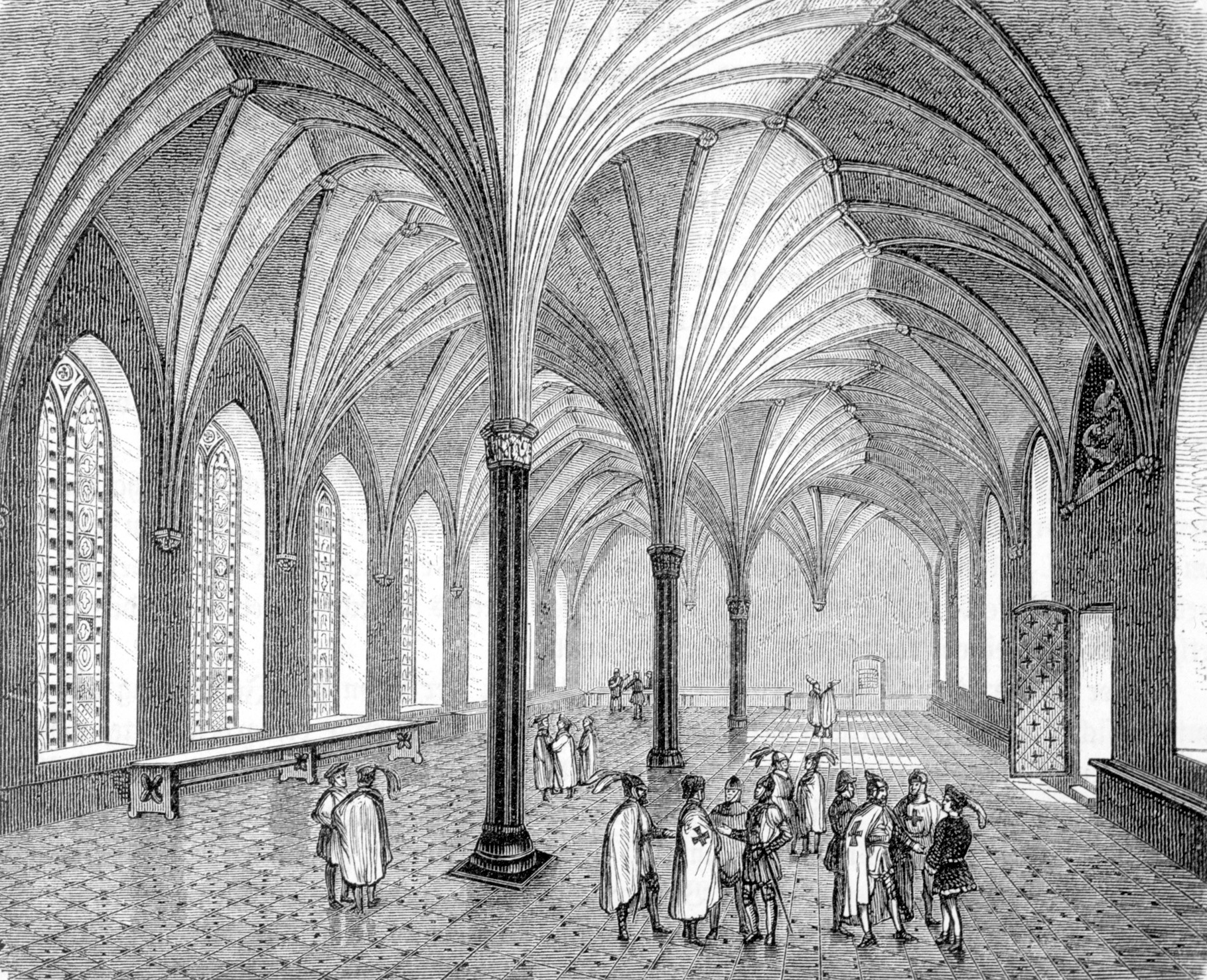

The story begins in the 12th century. The Teutonic Order originated in the assignment of religious knights to the defense of pilgrims, generally to and in the Holy Land, and a special hospital that had been established for German pilgrims. They adopted the “Rule” of the Order of Saint John, and were soon granted the same privileges as that order and the Templars, from whom they derived their military organization. Their “habit,” i.e., official religious uniform, consisted of a white surplice with a black cross, which most people recognize as Germany’s famous “Iron Cross.”

In 1291 the Order retreated from Palestine, the area again having fallen to the Muslims. The Teutonic Knights, however, was not left without a mission. Some decades earlier a crusade had been preached against the pagans of Prussia, who had violently resisted conversion to Christianity. In response to various murders, a new military order was founded, the Sword-Bearers, or Knights of the Sword. The organization met with little success. Finally, a Polish prince, Duke Konrad of Masovia, requested the assistance of the Teutonic Order. He offered the Knights the territory of Kulmland, roughly the southwest corner of today’s Lithuania and “whatever they could wrest from the infidels.” Eventually the Knights (or Brethren) of the Sword and another local order, the Order of Dobrzyn (“Dobrin” in German), were merged with the Teutonic Knights.

A 25-Year Campaign Against Pagans Of the Baltic

Then began a 25-year campaign. It was generally successful from an immediate military standpoint, but laid the seeds of more than a century and a half of conflict with Poland, east of Prussia, and Lithuania, east of Poland, and of far greater territory than we know it today. The area granted to the Knights became Germanized, and the administration was organized as a military unit. Constant reinforcements enabled the Order to hold its own against the pagans of the Baltic. Lithuanians were a particular target, being of the same ethnic group as the Prussians, who were eventually exterminated. Very little was done to carry out conversions.

This was the origin of the Ordenstaat, the realm of the Teutonic Knights. Knights and nobles from all over Europe took the opportunity to get in a few seasons of crusading in Prussia, a practice called “reysing.” The future Henry IV of England went on a reyse in 1390, as did Chaucer’s chivalric hero in The Canterbury Tales:

Full often time he had abroad bygone

Above all nations, to Prussia.

In Lithuania had he reysed and in Russia

No Christian man of his degree more often.

An Icy German Defeat By Nevsky Sowed the Seeds Of Antagonism

The Knights were not uniformly successful. Invading Russia from Germany in 1242, they were defeated by Prince Alexander Nevsky in the famous “Battle of the Ice” on Lake Peipus. At a crucial point in the battle, the ice broke under the Knights and swallowed up a major portion of the Germanic force, resulting in their utter defeat. This disaster seems to have embued the Teutonic Order with an even more violent antagonism toward the Slavs and the Balts, seemingly not tempered even when the pagans converted—nominally or otherwise—to Christianity.

Poles converted around the year 1000. An independent Polish Church was placed directly under the Pope, thus making it free of German influence. This independence naturally became a bone of contention with the Teutonic Order. Poland became and remained a secure ally of the papacy in the constant struggle between Emperor and Pope.

Conversion Of East Rendered Knights Irrelevant

But Polish resistance to the Holy Roman Emperors gave a quasi-religious justification for the animosity of the Teutonic Knights, who supported the Emperor. The Order turned on their presumed hosts, and began to take over large areas of Poland. They overran Gdansk (Danzig) in 1308 and massacred its Polish inhabitants.

The Lithuanians were converted to Christianity in 1386 on the occasion of the marriage of Grand Duke Jogaila of Lithuania (“Jagiello” in Polish) and Jadwiga, the Heiress of Poland (“Jadvyga” in Lithuanian, or “Hedwig” in German). Jogaila then became King of Poland and his cousin Vytautas the Grand Duke of Lithuania. At the same time paganism was effectively ended in that part of Europe, and the Order of Teutonic Knights again lost its raison d’être.

Rather than admit the inevitable or reorient the mission of the Order again, the temptations of temporal power proved too much to resist. To justify a continued crusade against fellow Christians, the Hochmeister (Grand Master) asserted that the conversion of the Lithuanians was invalid. This was the setting for the war which was to culminate in the Battle of Tannenberg.

New Hochmeister Tries For Diplomacy

The conflict didn’t happen immediately or inevitably, as many in hindsight always seem to assume. A new Hochmeister of the Order of Teutonic Knights was elected. This was Konrad von Juningen, who served from 1394 to 1407. He was reputedly an able statesman and, apparently, substantially less militaristic than his predecessors. Konrad saw that increased opposition from the Teutonic Knights would only unite the Poles and Lithuanians in a common cause. Konrad attempted to divert the attention of the Pole-Lithuanians from the Knights by instigating a campaign to drive the Tartar Golden Horde from the eastern borders of Lithuania. This was not a trick, as some historians have asserted, for Konrad sent a detachment of five hundred Knights to assist the Grand Duke.

But the campaign was a disaster. Vytautas and his army met Edegey Khan, Tamberlane’s second-in-command, in battle on the river Vorskla. Two-thirds of Vytautas’s army was wiped out, along with his dream of overcoming the Tartar threat once and for all. It also appeared to have finished the ability of Lithuania and Poland to make war. Having apparently helped settle—however roundabout—any potential threat from the Poles and Lithuanians, Hochmeister Konrad turned his attention to keeping the peace and avoiding open conflict with the other enemies of the Order.

A Dying Hockmeister Pleads Not To Elect His Brother

Unfortunately, Konrad died in 1407. His death, reportedly caused by gallstones, was believed to have been hastened by his unwillingness to take the cure prescribed by his physician: sleeping with a woman. Konrad was thus viewed as a martyr by the Order for refusing to save his life by committing a sin. His dying wish to the Knights was not to elect his brother, Ulrich von Juningen, Hochmeister. Konrad considered Ulrich, notoriously proud and headstrong, supremely unsuited for leadership. Konrad’s wishes were disregarded, however, and Ulrich was indeed elected Hochmeister. The new Grand Master had a distinct animus against the Poles and Lithuanians, and made little effort to conceal it.

In response to the sneers, insults, and manufactured incidents constantly offered by Ulrich, Jagiello countered with a number of measures as effective as they were probably ill-considered. Polish merchants were forbidden to trade in the Ordenstaat, making it clear that this hardship was somehow due to the Teutonic Knights themselves. The merchants in these areas were already upset over the Order’s trading ventures. Combined with the decline in the fortunes of the Hansa, the great medieval trading consortium, Jagiello’s measures cut deeply into the merchants’ already-reduced profits.

Knights Don’t Make Many Friends…

The duke of Pomerania, at Jagiello’s request, blocked the roads leading from Germany. At the same time Jagiello incited discontent among the Kulmerland junkers, small landholders owing fealty and military service to the Knights. The junkers were already feeling oppressed as a result of favor shown more recent settlers from the Rhineland. As a final insult to the Order, Jagiello stirred up rebellion among the Samogitians, recently conquered by the Knights. In consequence, open war broke out in 1409.

On November 30, 1409 Grand Duke Vytautas of Lithuania and his cousin, King Jagiello of Poland, met at Brasta, now known as Brest-Litovsk, to discuss the logistics of their campaign against the Teutonic Knights. The two developed an ingenious plan. Their respective armies were to rendezvous between June 29 and the of July 1, The following year near the monastery of Czerwiensk on the Visla (now called Vistula) River. They would then advance on the Order’s headquarters in Prussia, the Feistung Marienburg, a huge brick structure considered impregnable. This plan meant that the two armies would have to cross the Visla before they could advance.

Since there was neither a ford nor an existing bridge, Vytautas and Jagiello decided to construct a pontoon bridge in secret. Farming out the various sections of the bridge to separate locations in Poland made it more difficult for the spies of the Order to discover the plan. When completed, these would be transported with the army to the agreed-upon rendezvous.

Attack Preparations Made In Secret

Other preparations were made. Vytautas hunted the stumbras (European wood bison) in Bialovieza for eight days. He soon had 50 barrels of meat salted and shipped by raft down the Narew (Nemunas) and Visla rivers to the town of Plock, near the staging area of the planned battle.

Like the German High Command in World War II on the eve of the Normandy invasion, the Knights knew an attack was planned, but could not discover precisely when and where it was to be made. Consequently they reinforced all of their castles and guarded the usual passages across both the Visla and the Narew rivers. The Order assumed that the Poles would make their attack on the left bank of the Visla, and concentrated their forces at the Feistung Schwetz. Hochmeister Ulrich took up his post at Kauernick. A temporary truce was effected until June 24, but that did not halt active preparation for the battle.

Grand Duke Vytautas left his capital of Vilnius with his army on June 3. He was joined by contingents of the Rus (that is, Russians), and Tartar units under the Khan of the Tartars from Crimea (“Tartar Krim” or “Crim Tartary”).

Eastern Allies Muster A Formidable Army

The chronicles relate that, in all, Vytautas had 40 regiments or, in medieval terms, 40 standards. Remarkably for a medieval—or any—army, he reached the rendezvous exactly on time, June 29. There he joined forces with Jagiello, who had gathered the Polish host and added contingents of Czechs, Cossacks from Ukraine, a unit from Moldova, and Vlach (Bohemian) and Hungarian mercenaries under Jan Zizka, who was later to gain fame as the military genius of the Hussite wars.

Between them, Vytautas and Jagiello had assembled a force estimated at around 150,000 men. They had included every knight and man-at-arms they could summon from Poland and Lithuania. Virtually every people who might have a grudge against the oppression of the Teutonic Knights was represented, and this was most of the surviving population. Some sources are more conservative about the numbers, placing the size of the allied host around 100,000. The Polish contingent included at least 29,000 heavy cavalry and 10,000 infantry. The Lithuanians contributed an estimated 11,000 light cavalry and six thousand infantry.

Knights Build An Impressive Force Of Their Own

Opposing this heterogeneous allied force, the Knights were able to muster a force of about 80,000. This consisted principally of the Knights and their levies, volunteers from all over Western Europe (whom the Order termed “guests”), and mercenaries. The greater part of the Knights’ army consisted of heavy cavalry, generally more than a match for anything the enemy might throw against it, well-armed conscripts from their lands, including a large number of Kulmerland junkers, and a few arbalestiers using the new steel crossbows. They also had a limited number of cannon brought from Tannenberg.

The allied army crossed the Prussian frontier on July 9 and headed straight for Marienburg. The plan was to ford the Drweca (Dravanta) River, but the way was blocked with palisades manned by the Knights. On July 13 the army turned northeast to flank the Order’s position. On the same day they took Feistung Gilgenburg, and captured huge supplies of food. Just before dawn on the 15th the army found itself near the little village of Grunwald (or Grunfeld), facing the encampment of the Knights next to the village of Stebark, more widely known as Tannenberg. The area was circumscribed by the Mazurian marshes.

Poles To the Right, Lithuanians To the Left

The Polish-Lithuanian host immediately set about arraying themselves for battle. The sub-commander of the Polish contingent, Zydram z Maszkowice, positioned the Poles on the left flank, while Vytautas drew up the Lithuanians on the right. To inspire his men to greater efforts, Vytautas rode through his army without his bodyguard. Jagiello, the official commander-in-chief, assisted at Mass in his tent, which had been erected the night before during a terrible storm, which also soaked the ground, making movement by heavy cavalry even more difficult in the area’s soft soil.

The Teutonic Knights were slightly constrained by the fact that they were not joined by their brethren from Livland, roughly today’s Estonia and Latvia, who were delayed. Even so, and despite the fact that they were outnumbered almost two-to-one, the Knights were supremely confident of victory.

Their confidence was not entirely misplaced. Aside from the Polish knights and nobility, accoutered similarly to the Knights, the Polish and Lithuanian host was made up primarily of light cavalry and poorly armed Lithuanian tribesmen. These had recently converted to Christianity and still retained many vestiges of their former pagan culture. This was, in fact, the basis of the Order’s claim that their conversion was either illegitimate or a sham.

In fact, just before the battle, two pagan Lithuanians robbed the Catholic Church at nearby Litzbark, desecrating the Blessed Sacrament and making off with the gold altar vessels. Only a summary execution, ordered by Vytautas, quieted the outrage in both the Polish and Lithuanian armies.

Ulrich’s Hollow And Insulting Offer For Surrender

The Knights also numbered among their army the finest military commanders of the day. These included, of course, Hochmeister Ulrich von Jungingen, Deutschmeister (“Grand Marshal”) Frederick von Wallenrode, Grosskomtur (“Grand Commander”) Kuno von Liechtenstein, considered one of the greatest swordsman of the 15th century, and Trapier (“Quartermaster”) Albrecht von Schwarzenberg. All these took an active part in the battle. By any reasonable estimate, the Teutonic Knights could expect to run through the allied force like a mowing machine through a hay meadow.

Casting himself in the role of God’s champion, Hochmeister Ulrich disdained the suggestion of attacking without warning. He sent heralds to Jagiello demanding his surrender or a decision by force of arms. As a provocative gesture, hinting that his opponents were cowards, Ulrich sent two swords, one for Jagiello and one for Vytautas. The gift was doubly insulting, because that day happened to be Jagiello’s 60th birthday.

Naturally, Jagiello accepted the offer of combat and scorned the idea of surrender. In spite of his disparaging gift of weapons to the enemy commanders, Hochmeister Ulrich was probably undeceived about the possibility of surrender without a fight. It was likely he had sent the heralds with the offer only to comply with the strict laws of chivalry. Ulrich was extremely eager to begin the fight and wipe the “pagans” off the face of the earth.

Chivalry Be Damned

The Grand Master did not have long to wait. Jagiello in due course mounted and rode to the top of a hill to direct the battle. This threw the plan of the Knights into slight disarray, for they had expected him to lead the fighting personally. Ulrich had positioned the line to put Jagiello in the greatest personal danger—assuming that he would be leading the host in person. In any event, at approximately nine in the morning, the Poles sang the battle-hymn of Saint Wojciech and Jagiello gave the signal to start.

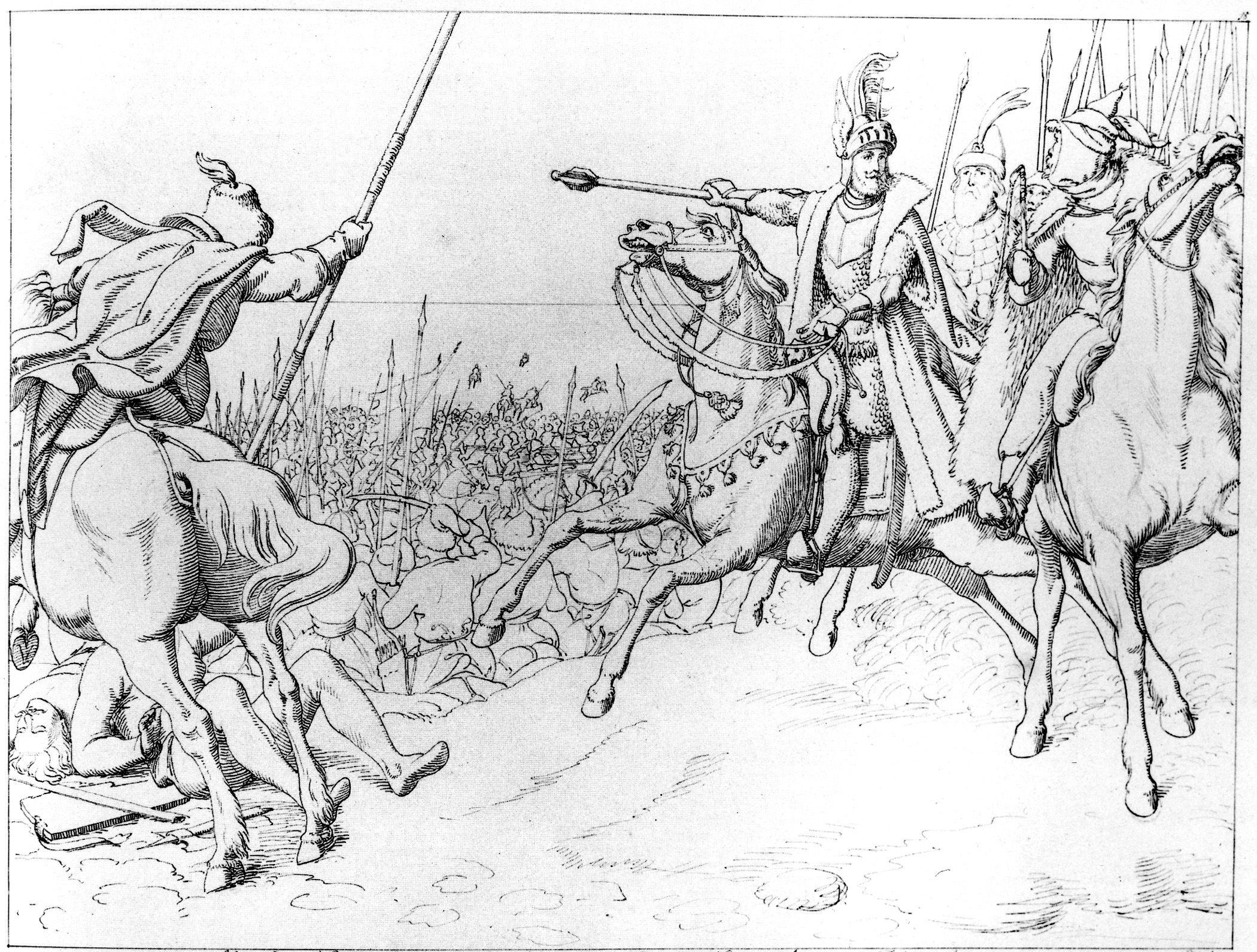

In spite of what the laws of chivalry might suggest, the Order opened the battle with an artillery barrage. This did not last long, however, perhaps because, as the representatives of the fading order of chivalry, the Knights may have been uncomfortable with such a dishonorable weapon. On the other hand, they may simply have brought insufficient powder and shot to be able to use their ordnance properly. In any event, artillery would have been of little use in the way the battle developed. In classic style, clad in plate armor and enclosed helmets, the chivalry of the Order launched their first assault, bellowing the ancient war cry, Gott mit uns! (“God with us!”).

A Solid Wall Of Steel

The Knights advanced against the Polish-Lithuanian front as a solid wall of steel. They succeeded in smashing the right wing, composed principally of Czechs and Lithuanians, and in nearly shattering the left wing. In spite of their obvious valor, the poorly armed Lithuanians were decimated. Refusing to retreat, however, even in the face of overwhelming force, relatively few of them were to survive the day. Casualties among the tribesmen were estimated between 30 to 50 percent.

In spite of the shock of the Knights’ charge, the center of the Polish wing managed to hold, eventually affording the Lithuanians and the allies a chance to rally. Meanwhile, Hochmeister Ulrich shifted some of the forces attacking the Polish heavy cavalry on the left over to the right to load more pressure on the Lithuanians.

Thus the first part of the battle went in favor of the Teutonic Order. Concentrating their efforts on the Lithuanian right, the Knights forced the Lithuanians to fall back. This appears to have been a fighting retreat, however, and not a rout, although contemporary chronicles relate that “the pagans were knocked off their feet,” and that the Lithuanians soon began a wild flight. In light of subsequent events, however, along with the discovery of a new account of the battle in 1963, what was recorded as a panic appears to have been a tactical move to lure the Knights into a disorderly pursuit.

Panic And Confusion Amongst the Tribesman

In this they were partially successful. Only the foreign “guest” knights broke ranks, the discipline of the Order forbidding such a move without orders. While the Teutonic ranks were disrupted, there was also a panic in the Polish ranks over the apparent desertion of the Lithuanians. The Czech contingent appears to have fled the battle altogether and sought the safety of the forest. The Teutonic Knights withdrew to reform and prepare themselves for another charge.

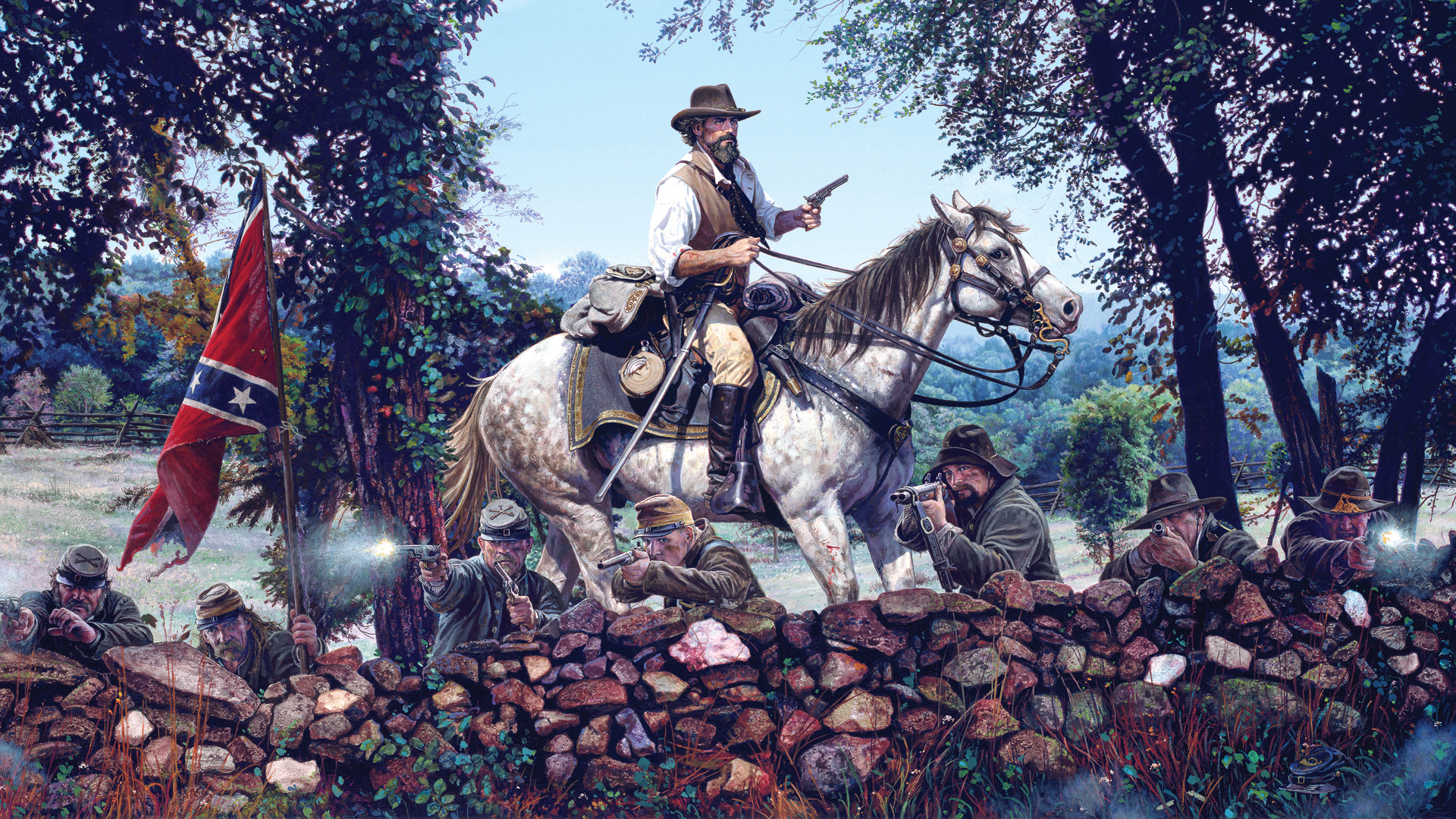

In spite of the confusion in their own ranks, the Polish center still managed to hold, giving the Lithuanians a chance to rally. Possibly to forestall positive action by the enemy, Hochmeister Ulrich ordered another charge before the Teutonic Knights’ left wing could reform. In a bold, but characteristically foolhardy move by the Grand Master, Ulrich committed the entire reserve, some 15 or 16 regiments, somewhat weakened by the earlier desertion of the Kulmerland junkers.

The Hymns Of Battle

Ulrich obviously anticipated a quick victory. But the Polish center, reinforced with its own reserves and the return of the Lithuanians and other allies, continued to resist, even though at one point the White Eagle flag, the royal standard of Poland, fell to the ground. Assuming that this meant that Jagiello was dead, the Knights of the Order prematurely began singing a victory ode, the Easter hymn, Crist ist enstanden (“Christ Is Risen). Some accounts relate that the Order sang the hymn just before the battle in response to the Polish anthem, but it seems more reasonable to assume that the Knights acted in accordance with their tradition.

Part of the advantage of the Polish knights lay in the fact that they had managed to anchor their line among the brakes and undergrowth of the marshy ground. Heavy cavalry is at its best in the open, and the Polish chivalry refused to cooperate by coming out of the brush and putting themselves at a disadvantage. The technical superiority of the Teutonic Knights should have more than made up for the foe’s numerical strength, but the terrain itself might almost have been said to fight against the Order.

A Strategic Blunder Causes Knights To Exhaust Themselves

In his pride, Hochmeister Ulrich seemed convinced that he need merely continue to throw his full force against the Polish-Lithuanian line in order to sweep away the enemy he held in such contempt. He continued to take the offensive throughout the long and bloody day, but the Polish line refused to break. This rendered the Knights’ superiority in heavy cavalry virtually useless. After squandering their strength and endurance in useless charges, the Knights were outflanked late in the day when the Poles finally decided to make a counter-charge.

The battle then degenerated into hand-to-hand combat, a sure recipe for maximizing casualties and the sudden shifts of fortune that can decide a battle in defiance of logic. The battle now went steadily against the Order. Accounts differ. Either the Poles and Lithuanians used a “Tartar tactic” of surrounding their foe, or the Tartar light cavalry itself made the encirclement, picking off targets with their short compound bows by their sheer number more effective than the crossbows of the arbalestiers.

Ulrich Receives Just Desserts

Still Hochmeister Ulrich refused either to retreat or surrender. He was soon to lose the opportunity for either. Probably having a sense that he was responsible for the debacle, he continued fighting, his gilt armor and white cloak of the Grand Master conspicuous beneath the great white and gold battle banner of the Order with its black cross and eagle. When his body was found after the battle, it was mutilated almost beyond recognition by the many wounds he had received, as well as the marks of individual fury vented against the author of so much misfortune.

The battle lasted over 10 hours. The army of the Order was completely destroyed as an effective force. The dead were reasonably estimated in excess of 18,000, with 14,000 taken prisoner. Among the slain were the Grosskomtur Kuno von Liechtenstein, Deutschmeister Frederick von Wallenrode, Albrecht von Schwarzenberg, the Ordensmarschall, and a great many of “Castle Commanders,” for a total of four hundred, a significant proportion of the Order’s officer corps. Among the prisoners were Marquard Salzbach and Andrew Sonnenberg, both prominent in the Order, whom Vytautas ordered executed for an alleged insult to his mother, Birute.

Knights Effectively Neutralized As A Fighting Force

Many of the captured knights were tortured or beheaded for acts real or imagined—there having been over a century and a half of incidents to inspire vengeance. Fifty captured banners were hung up as battle trophies in Krakow Cathedral. Whether or not the casualty figures are accurate, one thing remains clear. The threat to the burgeoning Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth represented by the Teutonic Knights was permanently ended.

From then on, until effectively destroyed as an independent and sovereign entity by the Reformation and the rise of nation-states in the wake of the French Revolution, the Knights assumed the role of an ordinary feudal overlord of the Ordenstaat. As for the Baltic and Slavic peoples of Lithuania and Poland bound in the common fight against their Teutonic foes, they signed the Treaty of Union of Horodlo in 1413. It lasted, somewhat weakly, until the 1700s, and by 1795, Lithuania was under the rule of Russia.

Join The Conversation

Comments