By William E. Welsh

Union Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside was prone to dithering. The vanguard of his 120,000-strong Union Army had arrived in Falmouth on the north bank of the Rappahannock River opposite Fredericksburg on November 14, 1862. Unfortunately, the bridging equipment that Burnside had ordered to be hauled in a timely manner overland in wagons would not arrive for a number of days.

Maj. Gen. Edmund Sumner suggested the advance force cross the river upstream via fords and occupy the heights, which were held by a few hundred Rebels, but Burnside worried the river would flood and cut them off. While Burnside considered a major crossing 10 miles below Fredericksburg at Skinker’s Neck to steal a march on Confederate General Robert E. Lee, half of Lee’s army under Lt. Gen. James Longstreet occupied the heights south of the town.

By the close of November, Burnside had his full complement of pontoon bridges, but the anxious commander of the Army of the Potomac believed that Lee had read his mind in regard to Skinker’s Neck. He therefore decided to battle Lee at the Battle of Fredericksburg. “I think that the enemy will be more surprised by a crossing immediately in our front than in any other part of the river,” Burnside wired Washington.

An Unrealistic Plan of Attack Against Entrenched Troops

Burnside’s plan called for Maj. Gen. William Franklin to cross on pontoon bridges directly below the town and roll up the Confederate line from south to north. Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. Sumner’s Right Grand Division would cross on another set of pontoon bridges directly across from the town and make a strong demonstration against the heights occupied by Longstreet. The Center Grand Division, which was commanded by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, was to be divided so as to support the attack of the other two grand divisions.

Burnside played directly into Lee’s hand. Longstreet’s I Corps, which contained about 35,000 men, had entrenched on the slopes of a seven-mile-long ridge that stretched from the town to a railroad stop known as Hamilton’s Crossing. The Rebel line was studded with artillery positioned to sweep the floodplain before it. When Longstreet suggested adding another gun in one spot, his artillery chief said it was not needed. “General, we cover that ground now so well that we comb it as with a fine-tooth comb,” said Colonel Edward Porter Alexander. “A chicken could not live on that field when we open on it.”

The engineers laid the bridges on December 11 under a steady shower of bullets from Brig. Gen. William Barksdale’s 1,600 Mississippians, who fired through loopholes they made in buildings on the riverfront. The following morning, a steady stream of Federal troops concealed by a heavy fog marched across makeshift bridges to the south bank. At that point Lee, who had requested the previous night that Lt. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, send part of his corps to reinforce Longstreet, told him to shift his entire 35,000-man corps to Fredericksburg. Longstreet’s five divisions would contest Sumner’s advance, while Jackson’s four divisions would deal with Franklin.

Seven Frontal Assaults Fail to Dislodge the Confederates

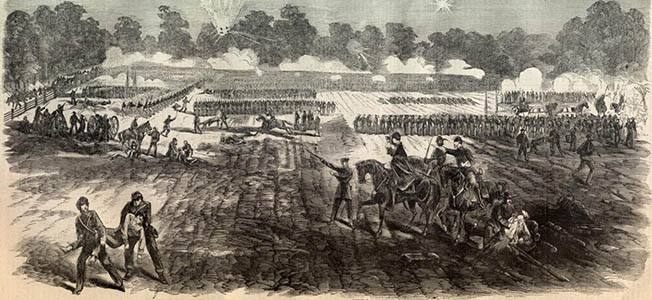

On December 13, the Federals attacked. Sumner’s and Hooker’s troops were slaughtered by Longstreet’s tightly packed lines behind the famous stone wall at the base of Marye’s Heights. During the course of the long day, the Federals would launch seven major frontal assaults against Longstreet’s densely packed ranks.

Franklin’s grand division never came close to getting a foothold on the low ridge south of the town much less rolling up Lee’s right flank held by Jackson. Jackson had deployed his largest division, Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill’s so-called Light Division, in the front line and could draw on an enormous reserve of three divisions. A tenacious assault by Maj. Gen. George Meade’s 4,500 Yankees struck hard through a swampy patch of ground in Hill’s line near Prospect Hill where no troops had been deployed. Franklin failed to reinforce the attack, and it was easily repulsed by a counterattack led by Brig. Gen. Jubal Early.

It was a costly and decisive defeat for the Union. Federal losses were 12,650 compared to Confederate losses of 4,200. The armies stayed in position until Burnside withdrew on December 15. Five weeks later President Abraham Lincoln replaced him with Hooker. With Confederate fortunes waning in other theaters, Lee’s winning Army of Northern Virginia became the South’s greatest hope for victory.

See the Battlefield as Lee Saw it at Lee’s Hill

The Fredericksburg battlefield is part of the greater Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania Military Park. The Fredericksburg visitor center is situated on the southwest side of town at the base of Marye’s Heights. It is worth taking some time to orient oneself at the visitor center by seeing a short film that gives an overview of the battle and looking at the museum exhibits. Rangers on duty at the visitor center can answer questions about the battle and the park. It is also worth taking the short trail walks from the visitor center to the Sunken Road and to the National Cemetery.

The auto tour contains six stops. The Sunken Road serves as the first stop. The second stop is Chatham Manor, an 18th-century home on the north bank of the Rappahannock River that served as Burnside’s headquarters. The last four stops are along Lee drive which winds south along the ridge past Lee’s Hill, where the Confederate commander observed the battle, to Howison Hill, which served as a commanding position for Confederate guns.

The auto tour continues to the site of Meade’s breakthrough and then to Prospect Hill, where Jackson placed masked batteries that served to break up Franklin’s attack. A short trail leads from Prospect Hill to Hamilton’s Crossing. At Hamilton’s Crossing, Major John Pelham, who commanded the Confederate horse artillery, fought with such distinction that he became a legendary among Confederate artillerists.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments