By Eric Niderost

On Friday, March 4, 1836, Generalissimo Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna Perez de Labron ordered a staff conference at his headquarters near San Antonio’s Military Plaza. The Mexican Army was in the midst of besieging a handful of Anglo-Americans and Tejanos (Mexican Texans) that were bottled up in a broken-down old mission locals called the Alamo. The rebels had held out for 11 days now, and His Excellency’s patience—never great when his prestige was at stake—was wearing decidedly thin.

Santa Anna had actually stepped down as president of Mexico to assume this command, but so far he had failed to win fresh laurels. His Excellency had envisioned a lighting-fast campaign that would throw the norteamericano “land pirates” off Mexican soil once and for all. After a promising start, he found himself bogged down before a ramshackle mission and the sheer frustration was starting to tell on his nerves.

The conference was held in a squat adobe building not far from the looming towers of San Fernando Church, the peacock brilliance of the officers’ uniforms standing in stark contrast to its whitewashed drabness. Major General Santa Anna appeared, a tall and handsome man of 43 whose height was made even more imposing by a cocked hat that sprouted red, white, and green plumes. Doffing this headgear, Santa Anna motioned to the officers and the conference began.

The Alamo Rebels Were Low on Food and Sure to Starve

Santa Anna came right to the point, saying he wanted to discuss the possibility of launching an all-out assault on the Alamo. Normally, his officers rarely revealed their true feelings, especially if they ran counter to the dictator’s will, but the sheer audacity of the statement caused passive façades to drop. The Alamo served no strategic purpose and part of its north wall had recently crumbled into rubble. The Alamo rebels were short on provisions; sheer famine would soon compel them to surrender.

Santa Anna listened to these arguments with an air of bemused condescension. His Excellency was encouraged by the fact that Colonel Francisco Duque had arrived with three full battalions of the First Infantry Brigade. Santa Anna had been irritated by the fact that Duque’s superior, Brig. Gen. Antonio Gaona, had granted the First Infantry Brigade five days of rest before pressing on. Gaona ignored Santa Anna’s express command to make haste, but now bygones could be bygones. Duque’s arrival boosted the Mexican Army’s numbers to about 2,500—more than enough to make an all-out attack.

Staff officers conceded these facts, but pointed out that a crucial element of the First Infantry Division had not yet arrived. The remainder of Gaona’s command, some 700 men and five guns, would not arrive for two or three more days. Two of those guns were 12-pounders, whose heavy cannonballs would knock down the Alamo’s already crumbling walls in short order. The Alamo garrison was isolated and there was no evidence of any reinforcements coming to their aid. Why waste lives on a fort that was bound to fall in a very short time?

These were sound arguments, but Santa Anna brushed them aside. “Against the daring foreigners opposing us,” his Excellency declared in his usual bombastic way, “the honor of our nation and our army is at stake.” No prisoners would be taken; Santa Anna intended to teach these “foreigners” a lesson.

General Joaquin Ramirez y Sesma, never missing an opportunity to curry favor with his chief, enthusiastically agreed. Other sycophants on the staff joined in the chorus of approval. Those who doubted the wisdom of the attack—and they were probably the majority—lapsed into tactful silence. Colonel Juan Nepomuceno Almonte, an aide who had been educated in the United States and spoke good English, reminded His Excellency that there would be heavy casualties. No matter, Santa Anna tersely replied, the nut must be cracked.

The matter settled, it was determined that March 4 and 5 would be devoted to planning the affair. The general assault would take place at dawn the morning of March 6, 1836. Santa Anna would later call the Alamo a “small affair,” not realizing his rash and bloody actions would create an American legend.

Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821, inheriting a vast domain that stretched from the borders of Louisiana to the shores of the Pacific. Unfortunately, Mexico also inherited a nearly insoluble Indian problem as well. Hard-riding Comanche and Apache raiders had plagued Hispanic Texas for decades, and their depredations seemed to be getting worse with the passage of time.

Texians and Tejanos

Then there was the problem of the United States, a dynamic, land-hungry nation of some 10 million people. The westward movement was well under way and there was a fear that the norteamericanos were casting covetous eyes on fertile, empty Texas.

The Mexican government decided to allow some American immigration, though under tight controls. Approving a plan that had been formulated earlier by Spanish authorities, the Mexican government allowed American Stephen Austin to establish an Anglo-American colony in Texas. These newcomers were called Texians to distinguish them from the Tejanos, or resident Hispanics.

The colony was a success, but over time cultural misunderstandings and stereotypes eventually festered into mutual antipathy. Mexicans considered most Americans crude barbarians, while most Americans considered Hispanics culturally and racially inferior.

At best the Americans were interested in accommodation, not assimilation. They were willing to be politically loyal to Mexico, but none of them really wanted to adopt Hispanic culture. They wanted to live as Americans, with the rights and privileges—such as trial by jury—they enjoyed at home. When they were denied such rights, resentment simmered.

The problem was compounded by the chaotic nature of Mexican politics of the period. Broadly speaking, there were two factions: the liberals (Federalists) and the conservatives (Centralists). The liberals favored more autonomy in the various Mexican states, a relatively weak presidency, and intellectual freedom. The liberals had helped frame the Constitution of 1824, which was inspired by the U.S. constitution.

By contrast, the Centralists favored a more conservative, authoritarian government in the old Spanish tradition, with a tightly controlled economy and strong support of the Catholic Church. Americans in Texas favored the liberals, since they were closer to American ideals.

Trouble started in 1830 when a centralist in power passed a law banning further American immigration. Texians were predictably outraged and Austin went down to Mexico City to see what could be done about the matter. He also wanted to discuss the creation of a Texas state within Mexico. Texas had been joined to the neighboring Mexican state of Coahuila in 1824 and the state capital moved from San Antonio to Saltillo, 365 miles away. Both Texians and Tejanos were equally upset by these developments.

During these years much hope was placed in General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, a leading liberal who had a considerable following. He had been elected president in 1832, but had retired to his hacienda at Jalapa. Santa Anna was still legally president, but allowed Acting President Valentin Gomez Farias much power.

The Generalissimo Expelled all Americans who had “Illegally” Entered Texas

Austin met with Gomez Farias, but made little progress. When Austin wrote back to Texas urging a separate state be established, the letter was intercepted by Mexican authorities. The ill-advised missive was tantamount to treason to the Mexican government, which threw Austin into prison for 18 months. He was eventually released on July 13, 1835.

Worse was to follow. General Santa Anna threw off his liberal trappings and marched on Mexico City. Acting swiftly, he deposed Gomez Farias, threw out the Constitution of 1824, dissolved the Mexican Congress, and ruled by decree. He was now governing as a Centralist, a dictator who was the darling of the reactionary elements of the country.

Santa Anna then turned his attention to the Texian problem. Many Mexican liberals had fled to distant Texas and it was felt that Americans must be sheltering them. The generalissimo also felt it was high time to curb these presumptuous norteamericanos. He would suspend their civil government, disarm them and, just for good measure, expel all Americans who had “illegally” entered Texas since 1830.

From the Mexican perspective, there was more than enough cause for alarm. By 1835-1836 Texian numbers had swelled to around 30,000, while the Hispanic population remained stable, roughly 4,000 people. Soon numbers would begin to tell and Texas would be culturally, if not yet politically, Anglo-American—an appendage of the United States. The onerous task of subduing Texas was given to Santa Anna’s brother-in-law, Brig. Gen. Martin Perfecto de Cos. General Cos landed 500 troops at Copano Bay and eventually marched to San Antonio de Bexar.

Hostilities finally began in a tiny little settlement called Gonzales, about 60 miles to the east of San Antonio. When Mexican troops tried to seize an old cannon, Texian settlers resisted and a skirmish ensued. The Mexicans withdrew, leaving one or two dead. None of the Texians had been killed and they were elated by their easy victory. A Texian “Army of the People” gathered, its goal to capture San Antonio.

The Texas Revolution could not have succeeded without the strong support of the Tejanos, or local Hispanic population. Many Tejanos were in sympathy with the liberal cause, passionately hating Santa Anna’s centralist despotism. Superb horsemen, they made ideal cavalry and were effective dispatch riders, scouts, and foragers.

A Consultation Convention created a provisional government, but opinion was divided over the best course of action. Some wanted complete independence from Mexico, but Austin and a new Texian leader named Sam Houston disagreed. They pointed out that such action was premature because they would alienate Tejanos fighting on the American side. In the end, the Consultation declared its intention to set up a Texas state within the Mexican Republic.

Henry Smith was appointed provisional governor and a council was established to serve as a legislature. Recognizing the need for a permanent fighting force, Sam Houston was made commander in chief of the regular Texas army. Unfortunately for Houston—and Texas—this army existed only on paper, because it did not include the volunteers who marched on San Antonio.

“Napoleon of the West”

The Battle of San Antonio de Bexar lasted from December 5 to December 9, 1835.

After much hard fighting, in which both sides displayed exemplary bravery, Cos was compelled to surrender. He and his defeated army evacuated Texas, pledging never to take up arms again. Jubilant Texians began to drift home.

Santa Anna has been called an enigma. A political chameleon, he changed allegiances as frequently as he changed his gaudy uniforms. A notorious womanizer, he loved luxury and was known to take opium on occasion. But enemies who wrote him off as a mere hedonist or libertine did so at their peril.

He styled himself El Napoleon del Oeste, “Napoleon of the West,” but the only trait he shared with the French emperor was ambition. Although far from being a Napoleon, Santa Anna was a good soldier who was capable of flashes of strategic brilliance.

In the meantime, Texas was falling rapidly into political chaos. Arguments, endless wrangling, and backstabbing recriminations were the order of the day. Fighting a common enemy seemed to be the only glue that cemented the Texian cause together. Once the Mexican Army left, the fragile unity shattered to pieces.

Dr. James Grant lobbied heavily for an expedition to the Mexican city of Matamoros, where the Rio Grande emptied into the Gulf of Mexico. Once Matamoros was taken, Texians could forge an alliance with Mexican Federalists that might eventually topple Santa Anna. Other Texians, not so high minded, practically salivated over the prospect of Matamoros plunder. Grant actually had an ulterior motive for urging an attack on the Mexican city: He owned extensive properties there and had been expelled.

The Legislative Council agreed, though Governor Smith and General Houston demurred. After much additional confusion and wrangling, men were assembled around the Goliad area and dubbed the Matamoros Expedition. It was an expedition that was to prove abortive. For the moment, Bexar and the Alamo were stripped of men and supplies to support the effort.

Niel’s Men Worked to Bolster the Alamo’s Defenses

Colonel James C. Neil was left to hold the Alamo with a skeleton force of 104 demoralized men. They were ragged, unpaid, and everything—especially powder—was in short supply. Neil was an artilleryman by trade and Cos had abandoned 21 cannon of various caliber when his army surrendered in December. The colonel didn’t have the transport to haul this precious ordnance away, so he decided to put it to good use and fortify the Alamo.

Mexican engineers had already created some gun platforms, but Neil was determined to make further improvements. On January 14, 1836, Neil wrote Houston that his men were in a “torpid, defenseless condition.” Bolstering the Alamo’s defenses at least gave the men something to do. Morale did seem to have risen; the men now had a purpose, which kept their minds off their wretched condition.

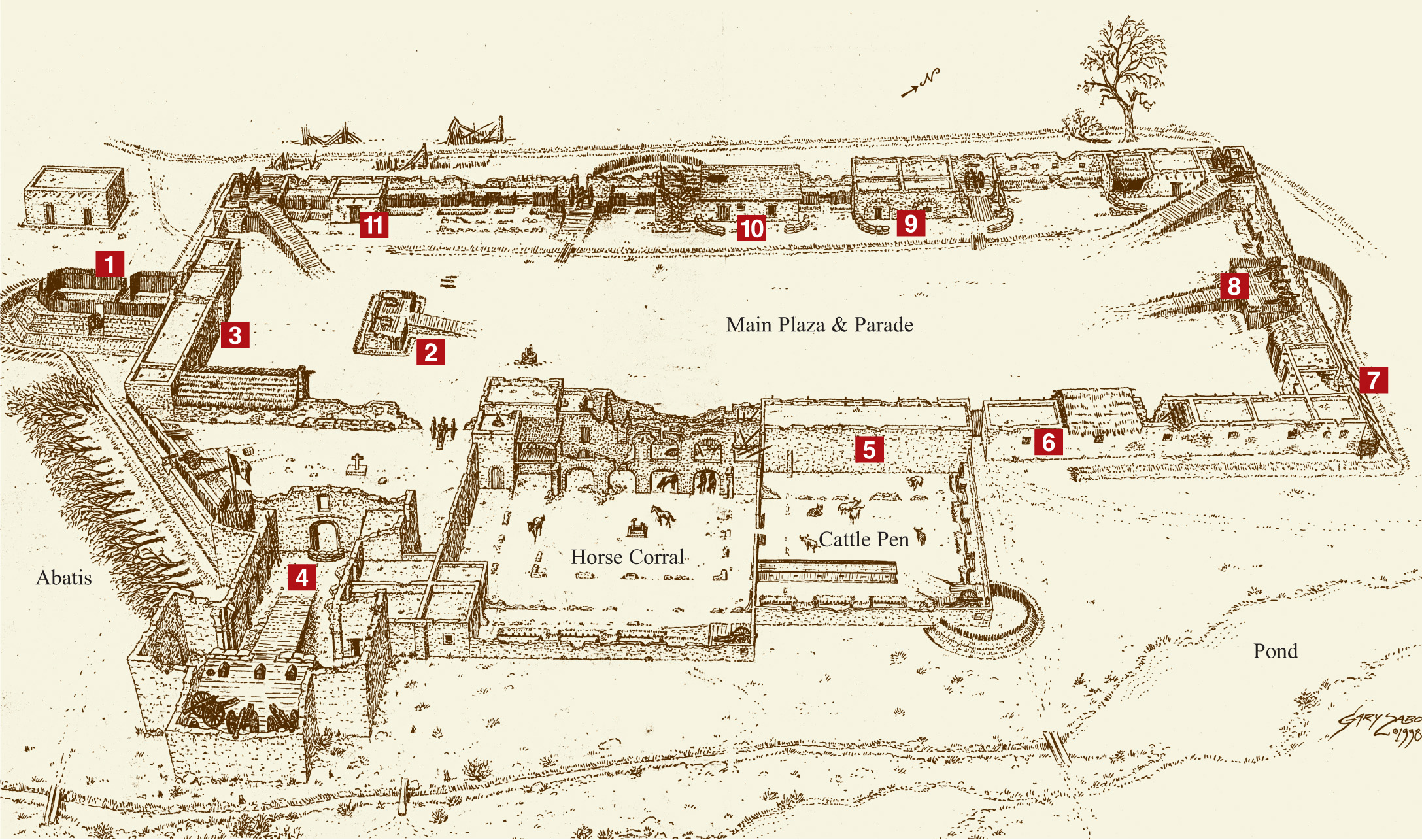

Green B. Jameson, a lawyer turned engineer, was responsible for the improvements. The Alamo was a mission complex that had originally been founded in 1718, though for the most part the structures dated from a later period. A succession of adobe buildings ringed the plaza and created a curtain wall about 12 feet high. The original intention of this wall was to protect missionaries and their Indian charges from hostile Comanches, not to fend off an entire modern army.

The Alamo Chapel was the anchor of the fort’s southeast corner. Built in the 1750s, it boasted limestone walls that were 22 feet high and 4 feet thick. The chapel façade looked much like it does today, but lacked the “camel hump” top that has transformed it into a visual icon. The “hump” was added about 1850 by the U.S. Army.

The chapel was open to the sky, the roof having been torn down by Mexican engineers to provide material for an artillery platform. This platform, called a cavalier battery, held three cannon of six-, eight-, and 12-pound calibers. A flagstaff was erected on one corner of the chapel that proudly flew a tricolor Mexican flag emblazoned by two stars. According to some sources, the two stars were symbolic of the combined states of Coahuila and Texas. According to legend—one repeated in many books, movies, and television accounts—the red, white, and green banner had the numbers “1824,” in reference to the 1824 Mexican constitution.

Just outside the chapel was the Alamo’s most vulnerable point. There was a 50-yard gap in the south wall. Jamison erected a wooden stake palisade to bridge the gap, supported by a ditch and an abatis of felled trees whose limbs had been sharpened and placed facing outward. The palisade also featured a firestep, which garrison riflemen would later put to good use.

The south wall was pierced by the main gate, so Jamison took extra care in his defensive arrangements. An oval lunette jutted out from the wall, its two (some sources say three) 6-pounder cannon designed to guard the gate and provide a measure of enfiladed fire from the south wall as a whole. The southwest corner was dominated by a large 18-pounder cannon, the largest piece of ordnance in the fort. Fired en barbette (over the wall), it faced in the direction of San Antonio de Bexar, just across the sinuous San Antonio River.

The Alamo’s Improved Condition Began to Give the Soldiers Hope

The northwest corner featured a gun ramp that held two eight-pounder cannon. These fired though embrasures cut in the adobe wall. The Mexicans called this corner “Fortin de Codelle.” A large pecan tree just outside the walls somewhat obstructed the view from the northwest corner.

Recent research has uncovered new evidence regarding the arrangements of the north wall. The north wall was a crumbling ruin when the Texians took over in December, its natural decay through neglect and erosion accelerated by the recent fighting. A cribbing—in essence, a palisade—of horizontal logs was erected immediately in front of the adobe wall, and the space between filled with earth as an added buffer. More earth was being piled on the other side of this cribbing when the sudden arrival of Mexican forces called a halt to the effort and left it unfinished.

Colonel Neil began to warm to the idea of holding the Alamo against possible Mexican counterthrusts. Originally, the Alamo was thought to be a kind of sentry post, providing an early warning for the main Texian settlements far to the northeast. Now, Neil saw the Alamo as a first line of defense that would block any Mexican moves up the old Camino Real. The improvements were going so well that the handful of Alamo men began to think that maybe, just maybe, it was possible to stop the Mexicans at San Antonio.

Sam Houston, nominally the commander in chief, wasn’t so sure. Houston had served in the U.S. Army and had sound military instincts. He knew that it was only a matter of time before Santa Anna was going to try and reconquer Texas. General Houston felt that, given the unsettled state of Texian politics and the sorry condition of this fledgling army, it was best to adopt a Fabian strategy of trading space for time: Lure Santa Anna into the hinterland and, in so doing, make him stretch his lines of communication and supply to the breaking point. Whittle away at his army through guerrilla warfare. Once the enemy was weakened, then and only then, accept battle. But trying to hold a broken-down mission did not enter into Houston’s overall strategic plans.

Houston dispatched James Bowie with some 20 men to San Antonio where they arrived January 19. The general wanted to have Bowie assist in the demolition of the Alamo and the removal of its cannon to Gonzales and Copano for safekeeping. Apparently, though, Bowie was told to use his own discretion in carrying out these orders. Houston also wrote a letter to Governor Smith in essence asking for the altered endorsement of his plan. Smith was more inclined to reinforce the post.

Meanwhile, Bowie was immediately impressed by the work that had been done to improve the Alamo defenses. James Bowie was a legend in his own time, famed for his adventurous life and the formidable knife that bore his name. Drifting into Texas, he adapted well and became a prominent landowner. But his happiness proved short-lived and after his wife and children died in a cholera epidemic he took to the bottle.

Niel Resolved to “Die in These Ditches” Before Surrendering

Heavy drinking had undermined his health, but he still was a charismatic figure who commanded respect from his friends and fear from his enemies. When the Texas Revolution broke out it seemed to give Bowie a purpose in life that had been lacking since his family’s demise.

Inspired by Neil’s leadership, the Alamo men were working wonders, though there was still much to be accomplished. The growing enthusiasm was contagious and soon Bowie was infected, writing the governor that “the salvation of Texas depends in great measure in keeping Bexar out of the hands of the enemy.” The knife fighter appealed for reinforcements and supplies at once, declaring that he and Neil resolved to “die in these ditches” before they would surrender the post.

Governor Smith decided to reject Houston’s arguments for razing the Alamo, preferring instead to send more men. Smith dispatched Lt. Col. William Barrett Travis and 30 men to join Neil’s miniscule force. Travis was a fiery 26-year-old lawyer who thirsted for fame. He kept a journal that recorded his sexual conquests in the crudest terms and had several bouts of venereal disease. Travis was a thoroughly human character, but his flaws do nothing to diminish his steadfast courage and resolve or his heroic death. On February 14, Neil left the Alamo on furlough and eventually Bowie and Travis assumed joint command.

The Alamo seemed to cast a spell on all who came within its walls. Soon Travis was writing letters that the old mission was the “key to Texas.” On February 8, the Alamo received an unexpected visit from David Crockett and his 12-man “Tennessee Mounted Volunteers.” Crockett, like Bowie, was a literally a living legend, famed throughout the United States as a great frontiersman, raconteur, and backwoods populist politician. His marksmanship was legendary, as were his tall tales and self-deprecating humor.

In the meantime, General Santa Anna was far from idle. In the fall of 1835, even before the news of his brother-in-law’s ouster reached Mexico City, his plans were well advanced. Any colonist—Texian or Tejano—risked execution, imprisonment, or exile. Rebel property would be forfeit, swiftly confiscated and redistributed to Santa Anna’s soldiers. Any “foreigner” caught under arms would be treated as a pirate without legal rights.

Once Santa Anna’s rubber-stamp congress endorsed these policies, it was time to plan the coming operation in detail. To begin with, Santa Anna decided on a swift winter campaign to surprise his enemies. Conventional military thinking held that a spring or summer campaign would be the wisest course. Winter storms would be over and the lush spring prairie grass that sprouted during the spring would provide fodder for the horses. The generalissimo spurned such considerations because he considered the Texas Revolution a personal affront.

There was also the route to consider. The Mexican Army could travel by sea up the Gulf Coast, landing at Co Bay. It was a time-honored route and one that was easier on the men and horses. Major General Vicente Filisola, Santa Anna’s second in command, was a strong supporter of a seaborne invasion. Filisola was an Italian who had served in the Napoleonic wars, so his opinion carried weight. Santa Anna ultimately spurned the idea as too time-consuming. A fleet would have to be outfitted, and naval operations on such a proposed scale would be almost impossible in the winter.

Santa Anna’s Army of 6,019 Men and 21 Pieces of Artillery Marched Towards Texas

That left the overland route, marching hundreds of miles up the old El Camino Real to San Antonio and beyond. It was rough country, with wide stretches of desert and mountains, but His Excellency gave little thought to such considerations. To him the Mexican Army was a mere tool, an instrument of his all-powerful ambition and will. It would do what was required, regardless of cost.

In late December 1835, the Mexican Army—now dubbed the Army of Operations—began the long trek northward to Texas. The army had 6,019 men and 21 pieces of artillery, all impressively uniformed and equipped, and they made a grand show when Santa Anna reviewed them. But Santa Anna’s whirlwind preparations had been too hasty in many respects. The Army of Operations lacked a medical corps to deal with the sick and wounded, a serious omission. Santa Anna had made some provisions for medical services, but somehow the concept had been lost in the shuffle, a victim of haste or indifference.

Medical care of a sort would have to be handled by the soldaderas or camp followers. It was a time-honored tradition for soldier’s wives and children to accompany their men on campaign. They would march hundreds of miles without complaint, cooking, cleaning, and tending the wounded with strength and compassion.

Santa Anna reorganized his army while on the march. A Vanguard Brigade (Brigada Avangarda) under Brig. Gen. Joaquin Ramierez y Sesma, composed of 1,400 men and 8 guns, would take the lead. Colonel (brevet Brig. Gen.) Antonio Gaona would follow with the First Brigade, 1,750 men and six guns. Another formation, the Second Brigade, some 1,700 men and six guns under Colonel (Brevet Maj. Gen.) Eugenio Tolosa, completed the reorganization of the infantry. Brigadier General Juan Jose Andrade’s Cavalry Brigade would provide the necessary horsemen for the operation.

The rebel Matamoros Expedition would be handled by dispatching Brig. Gen. Jose Urrea’s Independent Division, a mixed force of infantry and cavalry. Urrea would first destroy the Matamoros Expedition “pirates,” then sweep up the gulf coast and seize Goliad. The rebel link to the sea would be cut and their flank neatly rolled up. By the same token, Urrea would be protecting Santa Anna’s right flank as he swept into San Antonio.

“Six Soldiers of the Battalion of Yucatan Died From Exposure to the Cold.”

The trek to Texas proved a nightmare. As they neared the Rio Grande the Vanguard Brigade suffered from lack of water. A merciless sun and dust-clogged roads parched throats, until sweating men and horses were on the verge of collapse. Transport had broken down, and there were no water barrels. General Ramirez y Sesma sent an urgent message back to Lorado requesting water, but by the time the 30 barrels of water finally reached the troops they were half dead from thirst.

First heat and thirst, then bone-chilling cold. A Blue Norther—named by the blue-colored edge of the weather disturbance—occurs when a cold front sweeps down from Canada, gaining momentum as it goes. As the chill cold front collides with the moist, warm air of the Gulf of Mexico heavy snowfall results. Santa Anna’s troops stoically endured not one, but two Blue Northers on their march to Texas. On February 13, one Norther deposited 16 inches of snow on the ground. General Urrea reported that “six soldiers of the battalion of Yucatan died from exposure to the cold.”

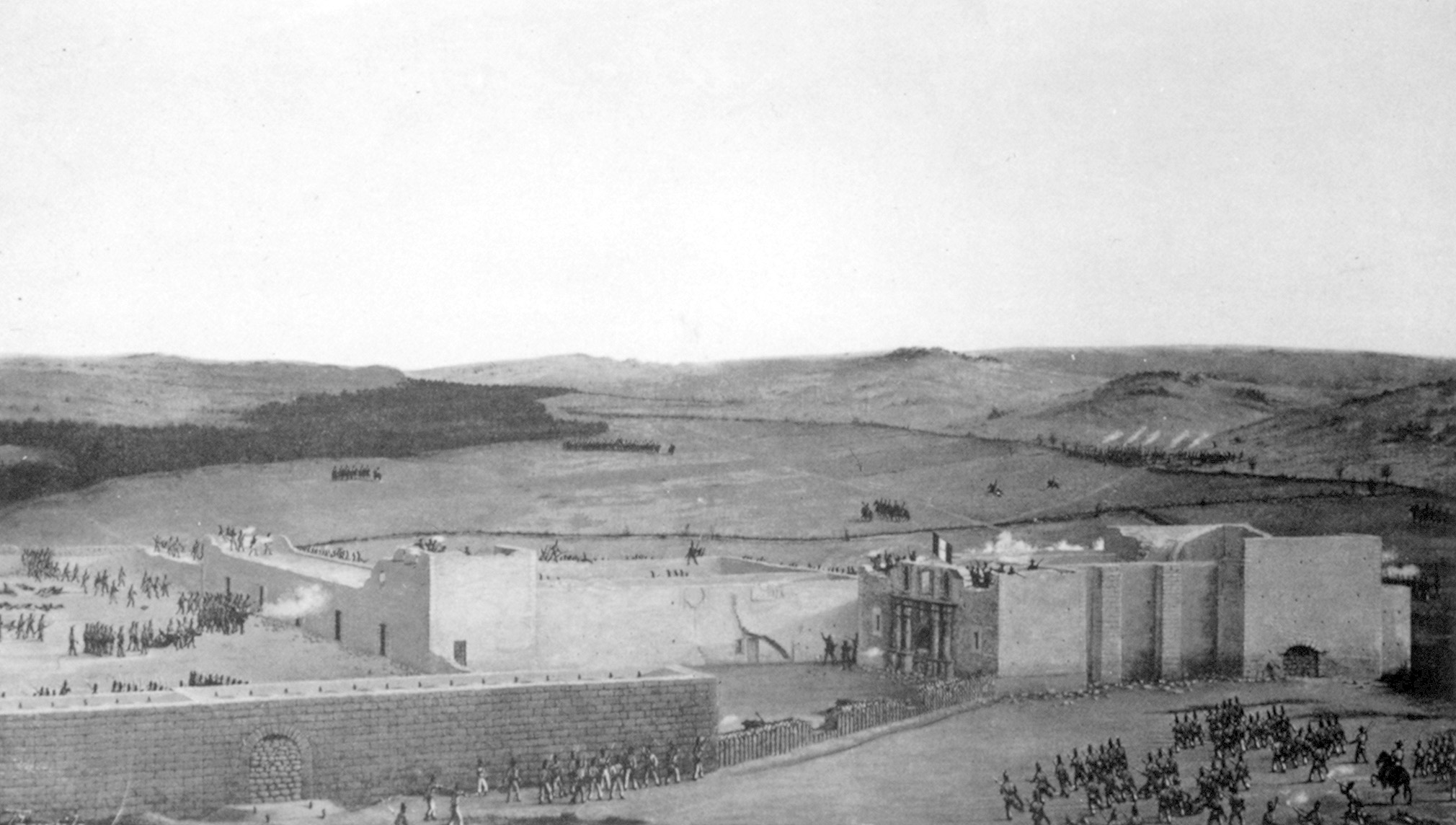

Santa Anna did allow his men some brief rest, but no more than two days. The Vanguard Brigade crossed the Rio Grande on February 15, only 120 miles from San Antonio. Heavy rains added to the misery and turned the roads into viscous quagmires, but nothing could stop their inexorable advance. The Mexican Army arrived at San Antonio de Bexar on February 23, having covered 120 miles in only eight days.

The Mexican Army had achieved almost complete surprise. Friendly Tejanos had brought word of Santa Anna’s approach, but Travis and Bowie felt he could not arrive until mid-March. In spite of Travis’s best efforts, the Alamo garrison was unprepared for a siege. Throughout the month of February little had been done to gather adequate stocks of food and firewood into the Alamo. A professional soldier would have cleared trees, brush, and small buildings from in front of the Alamo to deny the enemy cover and provide clear fields of fire, but Travis and Bowie were not professional soldiers.

On the evening of February 22, 1836, the people of San Antonio de Bexar and virtually the entire Alamo garrison staged a fiesta in honor of Washington’s birthday. It was a grand affair, with lively dancing, good food, and flowing tequila and corn whiskey. While San Antonio celebrated, leading elements of Santa Anna’s cavalry were only eight miles away. Santa Anna and the main body were camped on the Medina River, only 18 miles to the southeast.

After the fiesta, people drifted back home to their beds and many of the garrison staggered back to the Alamo to sleep it off. By midnight Bexar was quiet, but not for long. Word of Santa Anna’s imminent arrival spread throughout Bexar, prompting a hurried exodus among some of the townspeople.

The Mexican Cavalry Arrived near San Antonio at Dawn

A steady procession of lumbering ox carts and creaking wagons began to pour out of the town. Sensing something was amiss, Travis questioned some of the departing citizens and learned the truth—the Mexican Army was fast approaching. This intelligence must have come as a shock, but Travis kept his head. After all, the panicked flight might have been sparked by wild rumors. He didn’t know for sure, but just to be on the safe side he posted a lookout on the high bell tower of San Fernando Church.

Pale pink streaks of light appeared on the eastern sky, the first signs of dawn. As the morning wore on and the sun climbed higher, the lookout thought he saw twinkling specks of light dancing fitfully on the horizon. This could well mean sunlight reflecting off the lanceheads of Mexican cavalry, so the lookout lost no time in grabbing the church bell’s rope and tugging with all his might. The bell’s urgent peals echoed and reechoed over the town, alerting Travis to the danger.

Travis and Dr. John Sutherland joined the lookout in the bell tower, but could see nothing. As a precaution, Sunderland and a local resident, John W. Smith, mounted their horses and rode out to see if the lookout had been mistaken. Galloping up a hill, Sunderland and Smith drew rein when they saw the spectacle before them—Mexican cavalry of the Dolores Regiment.

Wheeling around, the two men spurred their horses into a gallop, but luckily they were not pursued. When the lookout saw the two men race back, he began to ring the bell some more. The bell’s sustained peals were a clarion call that the Mexican Army had at last arrived. The ringing transformed sleepy San Antonio into a hive of frantic activity. Men, women, and children rushed about, their arms full of belongings. Many of the Alamo men were still in San Antonio, half-groggy and hung over from the previous night’s revels.

Lieutenant Almeron Dickinson grabbed his baby daughter in his arms and made off for the Alamo, his wife Susanna close behind. Jim Bowie also made for the fort, but took care to see to the safety of his two Mexican sisters-in-law and nephew. It was a mad scramble, but the haste proved unnecessary. The Dolores Cavalry Regiment approached San Antonio cautiously, and in so doing missed a golden opportunity.

As it was, Santa Anna had originally ordered the troopers to break camp early and enter the city around dawn. The cavalrymen dawdled and their desultory movements proved Travis’s salvation. If they had arrived at dawn, they might have taken Bexar and the Alamo without a fight. Even later, if the Mexican troopers had pursued Sutherland and Smith into town, they might have caught half the garrison out in the open. But the moment was lost; a siege was about to begin.

Taking stock of the situation, Travis saw he had 146 men and three dozen noncombatants within the Alamo’s sheltering walls. Dispatch riders were sent out to plead for aid. A young man named Johnson was sent to Goliad, some 95 miles away, where a force of around 400 men were gathered under James W. Fannin. Another courier was dispatched with a message for Gonzales, some 70 miles away.

No Negotiations. No Surrender. No Mercy

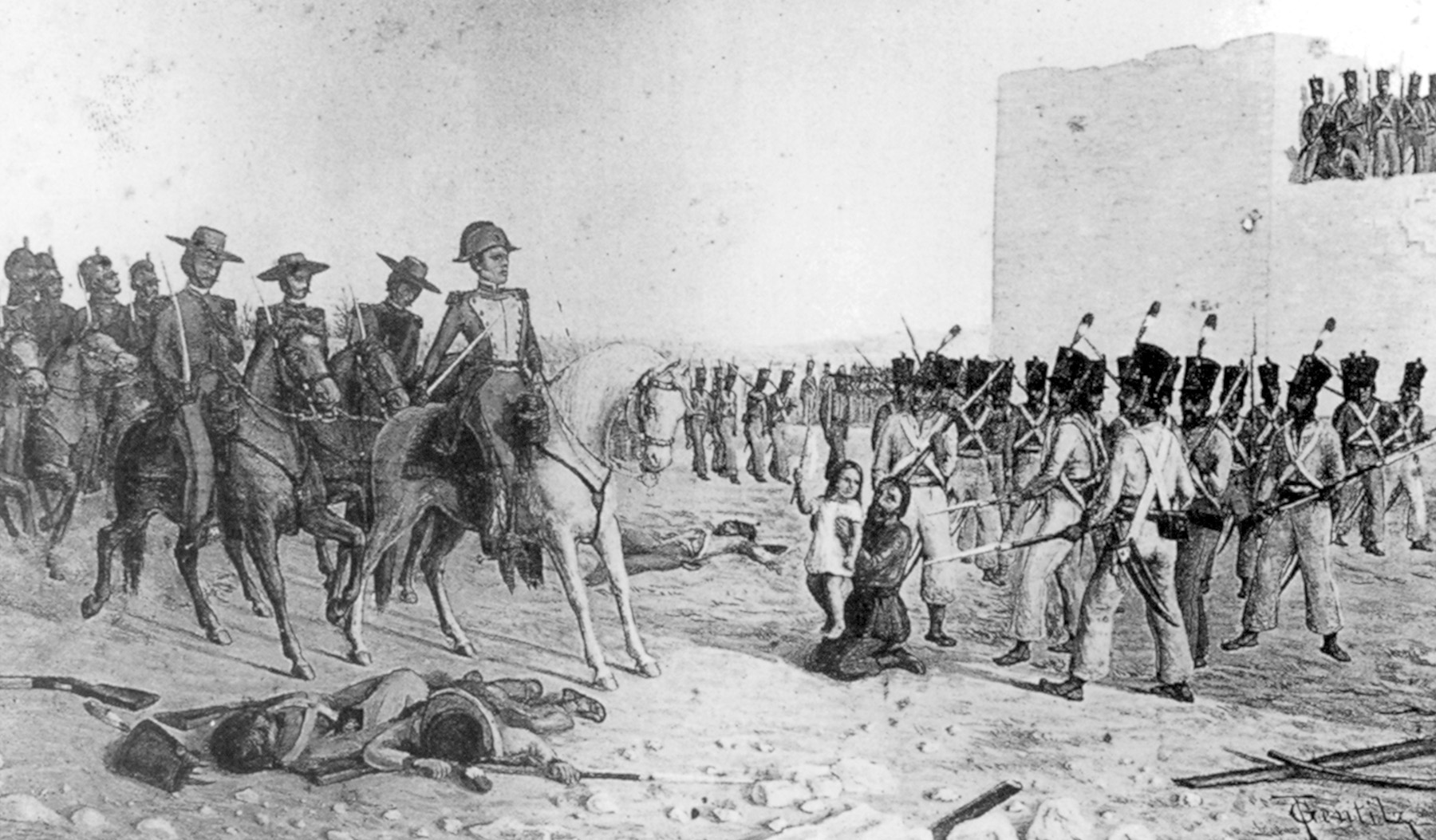

That same afternoon General Ramirez y Sesma’s Brigada Avangarda force of infantry and cavalry reached San Antonio. A blood-red flag was hoisted atop the bell tower of San Fernando Church. The crimson banner signified no quarter—no prisoners would be taken and the entire garrison would be put to the sword.

Santa Anna had arrived with the vanguard and at once ordered a bugler to sound “parley.” Travis replied by firing the Alamo’s enormous 18-pounder cannon. The cannon’s roar sent the Mexicans an unambiguous message of defiance. On the other hand, Jim Bowie was appalled by his co-commander’s rash response shot. The knife fighter was courageous, but not foolhardy and felt there was still room for negotiation.

Travis seemed to be burning his bridges, so Bowie sent Green Jameson under a flag of truce with a message to the Mexicans explaining that the cannon had been discharged before the parley call had been heard. Since he was fluent in Spanish, Bowie scribbled the note himself. Colonel Juan Batres, one of Santa Anna’s aides, delivered His Excellency’s reply: the Alamo garrison must surrender at discretion. In essence, that meant unconditional surrender, with the Alamo men throwing themselves on Santa Anna’s mercy. This was unacceptable, especially when considering Santa Anna’s past record. Travis also sent a messenger, who received much the same reply. The siege would continue.

The next day Bowie grew very ill. He was already in poor health, made worse by his heavy drinking, but now he went into sharp decline. He probably had typhoid pneumonia, but the truth will never be known for sure. Bowie’s protracted illness made Travis the sole and undisputed commander of the Alamo.

The Alamo had severe flaws. First, there was the crippling lack of numbers—there were simply not enough men to adequately man the perimeter. But it was the Alamo’s design that sowed the seeds of its downfall. Its adobe walls might break a Comanche arrow or stop a musket ball, but were vulnerable to modern artillery.

“Victory or Death!”

Santa Anna’s rapid advance to Bexar proved the Alamo’s temporary salvation. Much of his army was still strung out along the line of march and, more importantly, his heavy cannon were many miles away, bogged down by the heavy rains that turned the road into quagmires. Santa Anna’s 12-pounders would have gouged great bites of masonry from the Alamo walls, reducing the fort in a few days at most. Now he faced the prospect of a protected siege, with his light field pieces slowly nibbling away at the defenses.

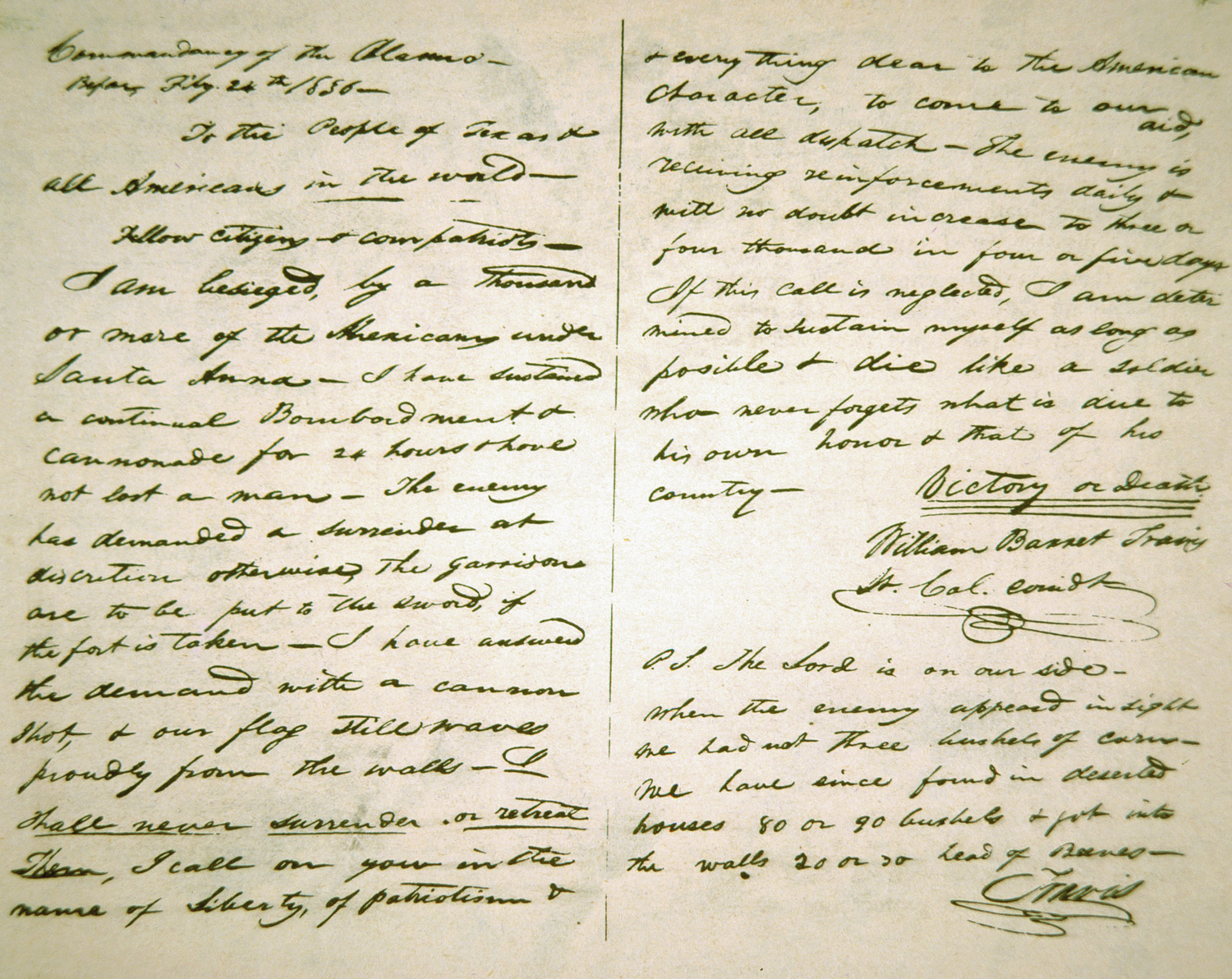

On February 24, Travis sent his famous letter, “To the People of Texas and all Americans in the World.” He appealed for aid “in the name of Liberty,” saying “our flag still waves proudly from the wall” and “I shall never surrender or retreat” He ended the missive with a bold “Victory or Death!”

To the modern reader some of the phrases seem overwrought clichés. Certainly, few military men today would sign a letter “Victory or Death!” Yet it was a bombastic age, and newspapers of the period show that hyperbole was the norm. Houston, Austin, and many others were guilty of such “purple” prose. Travis was prepared to give his life if he had to, but he was not suicidal. Much of the “overwrought” patriotism displayed in his messages was for public consumption—designed to create enough of a stir to bring timely aid.

Travis assigned Crockett and his riflemen to the most vulnerable part of the post, the stockaded gap between the chapel and the south wall. Crockett’s long rifles were formidable weapons, with a killing range of 200 yards or more. Travis himself commanded a battery of 9-pounders on the north wall. The enclosure was thinly held, so it was agreed that if the enemy caused a breakthrough, the garrison would fall back to the Long Barracks for a last-ditch stand. The inner rooms of the Long Barracks had been pierced to provide an interconnected defense, and loopholes had been bored in the walls. Some rooms featured cowhide barriers that were staked into the ground and filled with earth for added protection.

Santa Anna lost no time in sighting his cannon for an artillery bombardment. Two batteries of four guns each were placed about 1,000 feet from the Alamo. There were two 8-pounders, two 6-pounders, two 4-pounders, and two 7-inch howitzers. The howitzers could lob shells right into the heart of the fort.

The artillery barrage continued with little pause. Day after day, night after night, the garrison was subjected to an ear-splitting chorus of gunfire. Sleep was next to impossible and although the cannonade produced no casualties it did inflict considerable psychological damage. Within a few days the men were exhausted, their nerves stretched to the breaking point by the incessant hammering of the bellowing guns.

Exchanging Rifles for Bagpipes and Fiddles

The Alamo became less and less a refuge and more and more a claustrophobic prison. A siege mentality began to appear and nothing could stop the growing malaise. Exchanging his rifle for a fiddle, Davy Crockett serenaded the men in an effort to lift their spirits. While Davy earnestly scraped away on his fiddle, foot thumping in time with the music, 2nd Sgt. John McGregor played the bagpipes. The lively fiddle music combined with the bagpipe skirls to produce a musical duel like no other. One wonders what the Mexicans thought of the impromptu “concert.”

Such high moments were few and far between. At first, Alamo cannon flamed in counterbattery, but Travis soon realized he didn’t have enough powder to match the Mexicans shot for shot. The 18-pounder, for example, used up 12 pounds of powder with each discharge.

On March 1, the Alamo garrison was cheered by the arrival of 32 men from Gonzales. They were answering Travis’s appeal, even though they knew it was probably a doomed effort. Their arrival boosted Alamo numbers to about 189, but recent research suggests there many have been as many as 250 men within the walls.

The Mexican siege cordon around the Alamo was porous enough to allow couriers to slip past. Garrison letters and Travis’s continued pleas for aid were smuggled out with little difficulty. On March 3, James Butler Bonham arrived with a last, sobering message. Fannin would not be coming.

In the meantime, Santa Anna’s guns were moving ever closer. Some artillery was placed a mere 250 yards from the north wall. At this range, even relatively light caliber guns were effective. The north face was so weakened by the constant pummeling that part of it finally gave way and collapsed. Feverish repairs managed to plug the gap, but it was clear the Alamo could not hold for much longer.

It was obvious that Santa Anna was making preparations for a final assault and the beleaguered Alamo garrison prepared as best they could. Ammunition was getting low, but Travis distributed remaining stocks to the men. Sentries posted along the walls were given two or three additional muskets or rifles. Travis also penned a final appeal to Fannin, concluding the missive in the usual bombastic style of “God and Texas! Victory or Death!” About dusk in the evening of March 5, 1836, courier James L. Allen took the dispatches and managed to slip past the Mexican lines. Only 16 years old, Allen was the last messenger from the Alamo.

The Mexican guns fell silent on the evening of March 5. It was an ominous sign, but for the moment all the exhausted Alamo defenders could think of was sleep. The men were ragged, many of them having worn the same clothes for weeks or months and also half-starved from scanty rations. Red-rimmed eyes peered out from beard-stubbled faces and nerves were stretched tight from days of ear-shattering bombardment. Most of the garrison was asleep by midnight, but Travis continued to visit the various sentry posts until almost 4 am.

Surrender… Rejected!

In spite of all the “Victory or Death!” hyperbole, Travis apparently attempted to negotiate an honorable surrender that night. The Alamo commander chose a Bexarena, a local Mexican woman, as a go-between. The woman managed to leave the fort safely and deliver the message, but it was rejected out of hand by an enraged Santa Anna. The generalissimo wanted blood and no 11th-hour negotiation was going to cheat him of his prey. Santa Anna wanted a military victory that would cow the norteamericanos into flight or submission. Besides, he wanted to win fresh laurels and he knew that there could be no glory without bloodshed.

Santa Anna spent much of March 5 meticulously planning the general assault; nothing would be left to chance. The Alamo would be simultaneously attacked on all sides, increasing the odds for an eventual breakthrough. General Martin Perfecto de Cos would command the First Column, 200 fusiliers and riflemen of the Aldama Battalion and 100 fusiliers of the San Luis Potosi Activo (militia) Battalion. Cos would attack in an oblique fashion, striking the northwest corner of the mission compound.

A Second Column under Colonel Francisco Duque would attack the north wall, focusing on where it had recently collapsed and been repaired. There were some 400 men under his command, including three fusilier companies of the San Luis Battalion and the Toluca Battalion, the latter without their grenaderos (grenadiers). By contrast, the Third Column under Colonel Jose Maria Romero would hit the northeast corner with a force of some 300 men from the Matamoros and Jimenez Battalions.

A Fourth Column was assigned the palisade that bridged the gap between the chapel and the south wall. In theory, it was the fort’s weakest link, but Crockett’s crack riflemen and the abatis of trees made it a dangerous assignment. Colonel Juan Morales’s Fourth Column would be composed chiefly of cazadores (riflemen) of San Luis Potosi, Jimenez, and Matamoros Battalions.

Hedging his bets, General Santa Anna formed a reserve composed of some of his best men. Colonel Augustin Amat would lead these troops, five companies of grenadiers and the celebrated Zapadores Battalion. Although numbering around 185 men, the Zapadores were the best unit in the Mexican Army, elite in every sense of the word. In spite of their name—Zapadores translates to “engineers”—they were not true engineers, but an infantry unit.

The attack was to commence at dawn, so the troops bedded down early to get what rest they could. The Mexican camp started to stir after midnight. Sergeants prodded the men awake and the groggy soldados reached for weapons and rubbed sleep from their eyes. Soldiers were to take their assigned positions as silently as possible, the better to achieve surprise. There were some regimental variations, but in general the Mexican soldiers were dressed in Napoleonic style. Most troops had blue tunics with red facings, white or blue trousers, and tall leather shakos.

The attack would be made in column formation, large blocks of men packed into serried ranks. A column had the advantage of mass and it looked formidable, but as a tactical formation it was vulnerable to artillery fire. By about 4 am the columns were in position at all points of the compass. Some of the nearest Mexican columns were only about 250 yards from the Alamo walls.

“The Mexicans are Upon Us, and We’ll Give Them Hell!”

So far they had escaped detection, but the troops grew restless as they waited for the order to advance. Then, without warning, a solitary soldier cried “Viva Santa Anna!” The cry was taken up by others, hundreds of throats joining into a swelling chorus that also included “Viva la Republica!” A scowl darkened Santa Anna’s features when he heard the cheers, because he knew these “imprudent huzzahs” would alert the enemy.

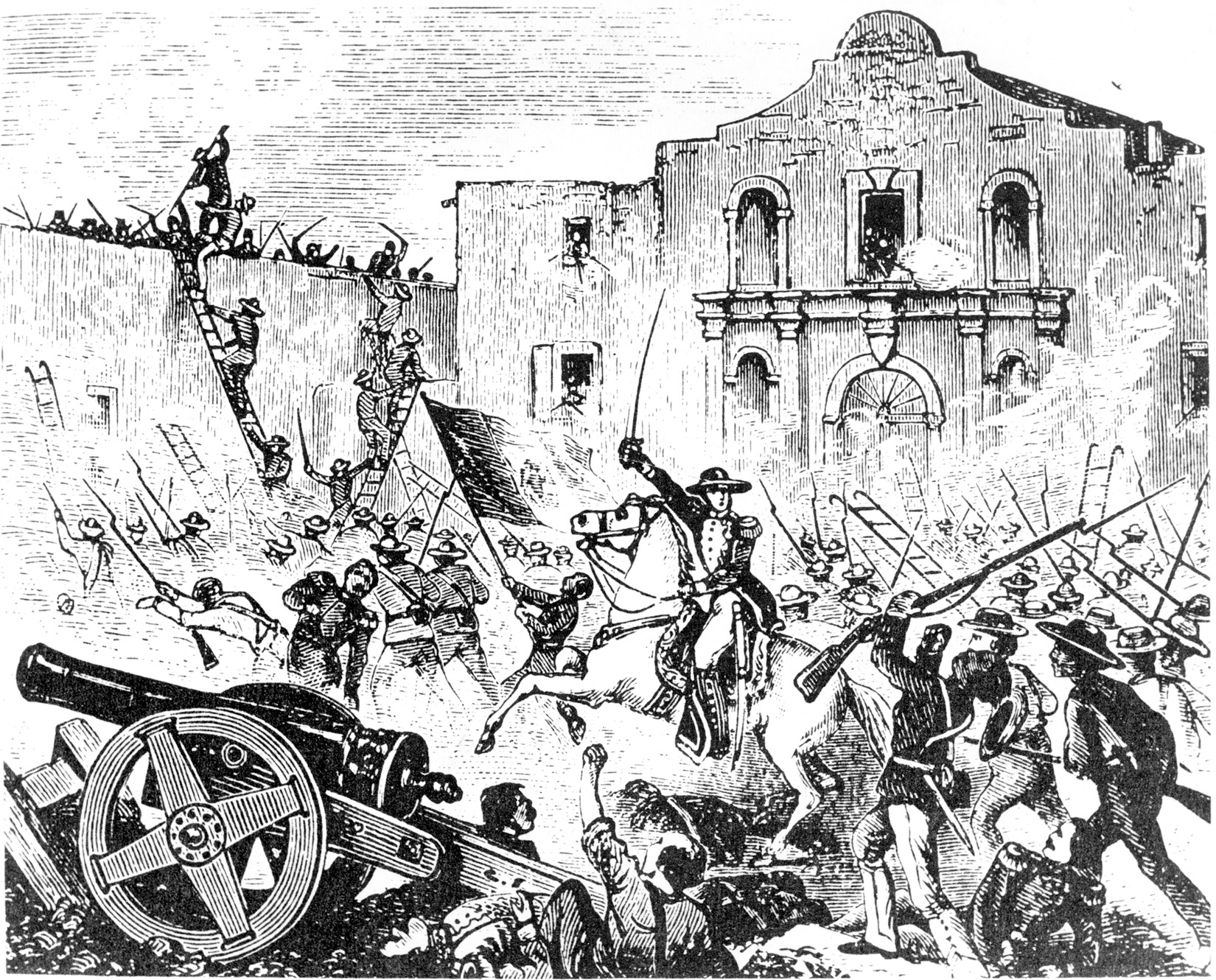

The damage was done, so Santa Anna ordered Bugler Jose Maria Gonzales to sound the Adelante, or advance. The brassy bugle notes rose above the echoing cheers, causing the massive columns to lurch forward. Officers took up the cry, shouting Arriba! and Adelante! to the men as they waited in the densely packed ranks.

It was now shortly after 5 am and a smear of light on the eastern horizon heralded the coming of a new day. The moon was almost full, but its pale beams were muted by scudding clouds. Back in the Alamo John Baugh, who had just come on duty, heard the commotion and peered through the murky half-light of dawn. Dark undulating masses seemed to be rolling up to the walls like an inexorable black tide. Baugh realized that these dark shapes were columns of Mexican soldiers.

Baugh raised the alarm at once, shouting, “Colonel Travis! The Mexicans are coming!” Travis was sleeping in a cot, his African American slave Joe sleeping nearby. The shouts and noise awakened both men and Travis jumped to his feet and grabbed his weapons. Running to his battle station on the north wall, Travis yelled, “Come on boys, the Mexicans are upon us, and we’ll give them hell!”

The Alamo defenders swarmed out of the buildings that lined the plaza like hornets stirred from their nest. Sentries fired rifles and muskets into the onrushing columns, but for the attackers the worst was to come. Lacking proper canister, the garrison had loaded their artillery with anything that could be salvaged from the area: bits of metal, nails, chopped up horseshoes, and even bits of door hinges.

The First to Fall

Colonel Travis was among the first of the defenders to fall. He managed to empty his shotgun into the mass of oncoming Mexican soldiers, but moments later was stuck in the head by a bullet. The impact knocked him to the ground, where he lay in stunned silence for a moment, then died.

Tiny bursts of light twinkled from the Alamo walls, telltale muzzle flashes from the defenders’ muskets and long rifles. Mexican soldiers began to fall, leaving gaps in the ranks that sergeants made sure were quickly closed up. Then the Alamo cannon sprang to malevolent life, muzzles spouting flames and smoke with deafening roars.

Lethal sprays of hot metal thudded into bodies, tearing, rending, and butchering with grim impartiality. Chests fountained blood, heads were severed, and limbs were torn off and flung carelessly into the ranks. Soldiers were hurled backward, crashing into the earth like broken dolls, their nearby comrades hit with bone fragments and splashed with blood and gore. Whole files went down before this fury, the ranks behind stumbling on the mutilated corpses of the dead and the writhing, screaming bodies of the wounded.

The hot blasts of canister wilted the Mexican attacks, but the Alamo defenders were taking casualties, too. The jerrybuilt parapets often exposed the upper parts of their bodies, and they were also silhouetted by the muzzle flashes of cannon, musket, and rifle. After some regrouping, the Mexican columns went forward again. Lashed by a hail of lead and metal, the First, Second, and Third Columns converged in the direction of the north wall. When Colonel Duque was badly wounded by a piece of canister, command of the Second Column passed to veteran campaigner Brig. Gen. Manuel Fernandez Castrillon.

Colonel Morales was also having troubles along the northeast palisade that connected the chapel and the south wall. The abatis made a crude but effective barrier and Crockett and his Tennessee boys were living up to their reputations as crack shots. Their ranks thinned by Crockett’s marksmen, Morales’s men started to drift westward, swinging around to attack the southwest corner and its powerful 18-pounder cannon.

The southwest corner was promising, but the main Mexican effort centered along the north wall. Although the columns suffered heavy casualties, clusters of Mexican soldiers managed to reach the wall’s base. The 9-pounder cannon couldn’t be depressed low enough to deal with them, so they were relatively safe. The defenders who tried to shoot down over the wall were themselves exposed to Mexican fire.

At this critical juncture Santa Anna committed his reserves, which tipped the balance in his favor. The generalissimo also ordered Bugler Gonzales to play the Deguello, an old Spanish tune that signified no quarter or mercy to the enemy. The reserves pumped fresh troops into the battle line and the Deguello—the call now taken up by other Mexican bugles—gave the attackers fresh heart. Colonel Jose Enrique de la Pena, who was with the elite Zapadores, remembered the chilling call “inspired us to scorn life and embrace death.”

Most of the Mexican ladders either were out of action or else had not arrived, but the part of the north wall that had recently collapsed and had been repaired showed promise. The timber and earth repairs had indentations and pockmarks that made good footholds. Brigadier General Juan Almador, assuming an active fighting role usually performed by junior officers, climbed up the wall with a handful of survivors from the shattered Toluca Battalion.

A Flood of Mexican Troops Entered the Walls of the Alamo

At almost the same moment General Cos’s Aldama Battalion started seeping over the west wall. Some of them used crowbars and axes to open blocked windows, others broke through cannon ports, and still others simply climbed over. The defenders had taken many casualties and there were simply not enough men to cover the whole perimeter.

General Almador and his men reached the top of the north wall, then scrambled down into the Alamo plaza. Finding a small postern gate, they opened it, allowing a flood of Mexican troops to enter the Alamo.

With Mexican troops now pouring into the plaza, surviving defenders abandoned the north wall. Those who could retreated to the Long Barracks. Unfortunately, in their haste the Alamo gunners did not spike the cannon, including the all-important 18-pounder.

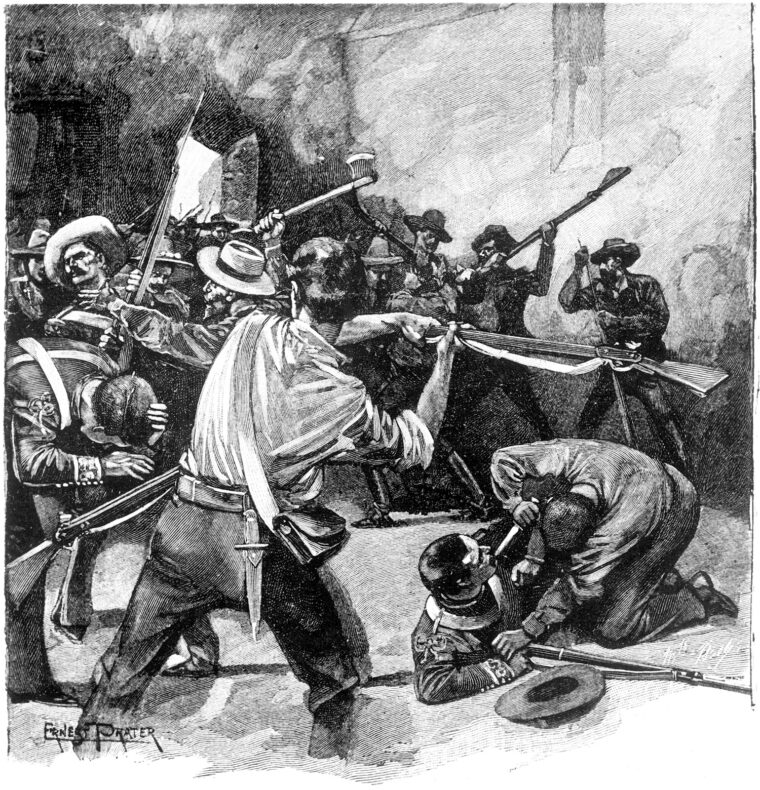

The fighting in the Long Barracks and the surrounding buildings was particularly brutal and bloody. Defenders fought with clubbed muskets, Bowie knives, or whatever they could find as a weapon. Cornered men fought on till shot down or pierced by bayonets. A few tried to surrender, but were ruthlessly cut down.

The Mexican troops had just endured a waking nightmare of torn bodies and eviscerated flesh. Friends and companions had been literally blown apart or were writhing in agony just outside the walls. The sheer horror of it all hardened hearts and produced a battle-crazed blood lust. Texian/Tejano wounded were killed and even a cat discovered in the rubble was quickly bayoneted.

Recent research shows that some defenders tried to escape by slipping over the wooden palisade that had been defended by Davy Crockett’s men. But Santa Anna had truly thought of everything. A screen of Mexican cavalry quickly rode them down and impaled them on lances.

The chapel was the last to fall. Davy Crockett and his Tennesseans were overwhelmed by sheer numbers. The captured 18-pounder blew open the chapel door and the Mexicans rushed in, cutting down everyone after a brutal fight. Robert Evans, one of the last defenders, was cut down while trying to thrust a torch into the powder magazine.

The Battle of the Alamo was over and Santa Anna had his victory. The whole area was a place of horror, a scotched ruin strewn with corpses, smeared with blood, and filled with the acrid stench of spent powder. Surveying the carnage, Santa Anna was unimpressed, calling the mangled corpses “chickens.”

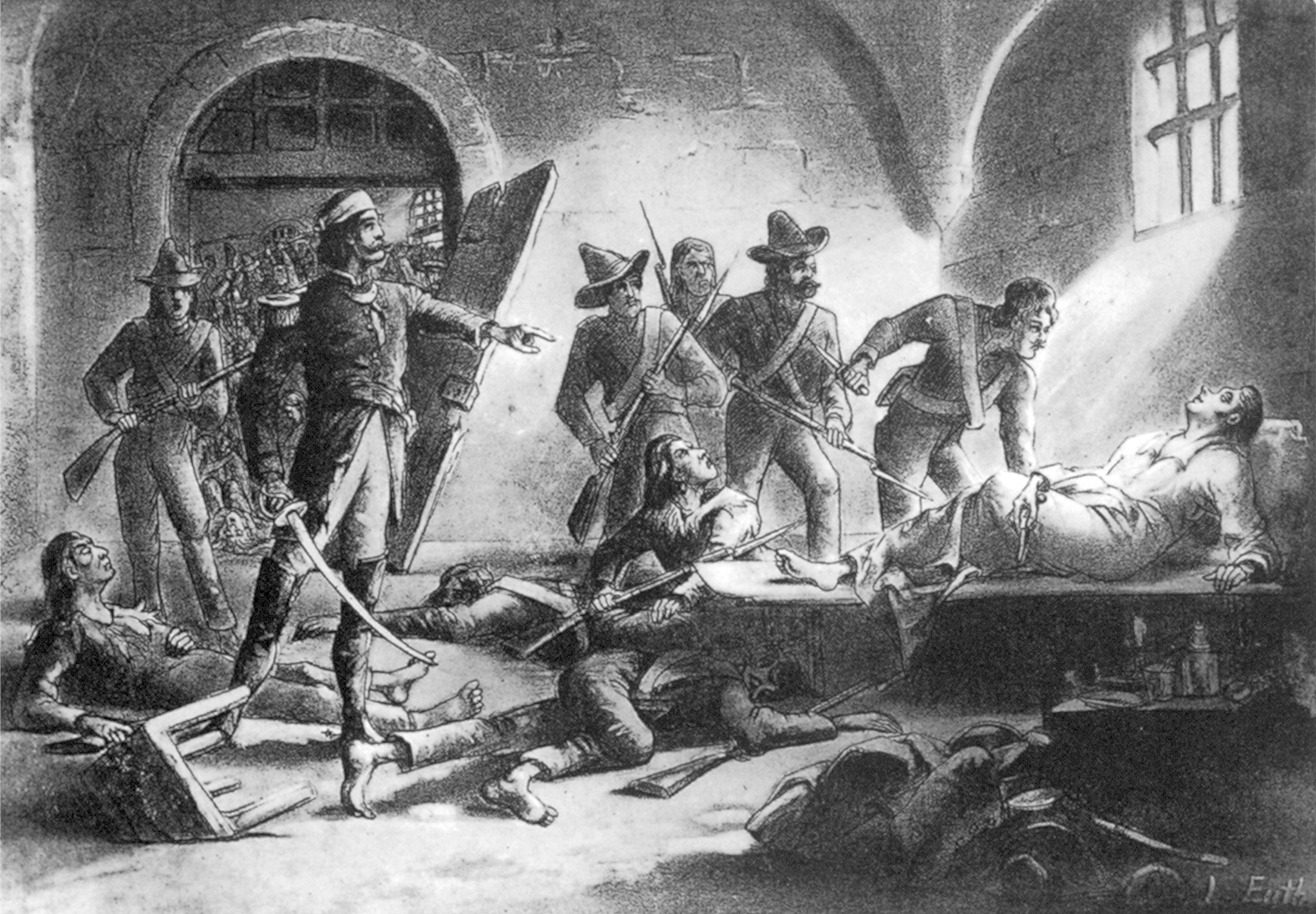

Defenseless Prisoners Were Hacked to Pieces by the Mexican Swords

General Castrillon somehow managed to rescue six or seven prisoners from the general slaughter. When the general tried to present these men to Santa Anna, His Excellency dismissed the gesture with a scowl and ordered that they be executed on the spot. Most of the Mexican officers were honorable men who looked upon the killing of defenseless prisoners with horror and revulsion. Some of Santa Anna’s sycophants, eager to do their master’s bidding, rushed on the prisoners and hacked them to pieces with swords. Colonel Jose Enrique de la Pena remarked they died bravely, “without complaining and without humiliating themselves before their torturers.”

Davy Crockett’s death has been the subject of controversy in recent years. There are sources—some of them of dubious authenticity—that claim Crockett was captured and executed with the six others spared by General Castrillon. Crocket is such an icon of American history it seems “heresy” that he didn’t go down fighting to the end. It’s certainly possible that he was taken alive. All that we can say for sure is that Crockett died a brave man.

There were a handful of survivors, including Travis’s personal slave Joe, Susanna Dickinson and her infant daughter Angelina, and some Mexican women and children. In the frenzy of battle, Mexican soldiers killed two older boys, but officers managed to spare the rest.

Casualties will never be known with absolute certainty. Santa Anna lost somewhere between 500 and 600 dead and wounded, many of them the cream of the army. Dozens more died of wounds for lack of proper medical treatment. Alamo casualties probably stood somewhere around 200, perhaps more.

Morality apart, Santa Anna’s ruthless slaughter of the Alamo garrison was a blunder of monumental proportions. The news of the Alamo initially produced a panic among the Texian settlers, but in time this panic gave way to a burning thirst for revenge. A few weeks later, on April 21, 1836, Santa Anna was defeated and captured at the Battle of San Jacinto. Led by Sam Houston, the Texian army had been inspired by the battle cry “Remember the Alamo!”

There were once giants in the land. History is both a blessing and a curse. I can at once read about men of valor and undaunted faith who built this nation, but then know that age of brave souls evolved into the decadent, debased, godless stain on a map in which I now live.

That was extremely well written and really brought the event to life for me in my mind. Well done.

“Victory or Death.” Stuning battle!