By Dr. Carl H Marcoux

The American war in the Pacific proved to be largely a maritime endeavor. Fighting consisted of widespread naval battles between the two major opponents followed by American invasions of Japanese-held island bases. The strategy decided on by the U.S. high command consisted of taking and securing these bases one by one and moving toward a possible invasion of the Japanese home islands.

To accomplish this mission, large numbers of fighting men and vast amounts of equipment and supplies had to be moved from the U.S. mainland to the staging and combat areas. Estimates called for the movement of seven to 15 tons of supplies and equipment to support each soldier for each year of overseas service. The U.S. Merchant Marine played a major role in this critical transportation task. Merchant ships and their crews accompanied every major invasion of Japanese-held islands throughout the Pacific Theater.

Naval Action in Three Phases

Japanese naval action against American shipping occurred in three distinct phases. The first, immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, consisted of the capture or sinking of American ships at sea or berthed in ports of countries seized by the Japanese in the first few weeks of the war. The second phase, from mid-1942 until October 1944, involved the attack by Japanese submarines on single merchant vessels, generally sailing alone rather than in convoys. The third and final phase featured suicide attacks by planes, manned bombs, or torpedoes on ships berthed or lying at anchor at invasion sites.

First Phase: December 1941

Immediately after Pearl Harbor, the United States Merchant Marine was ill equipped for its crucial role that was to follow. The Japanese seized every ship flying the American flag in the Asian ports that they captured. Moreover, the bombing of Pearl Harbor served as a signal to the Japanese submarines at sea to begin action against American ships then currently sailing across the vast stretches of the Pacific. The German government joined its Japanese allies and began a campaign of destruction on Atlantic seas as well. In the three weeks following December 7, German U-boats sank 25 ships off the U.S. Atlantic coast, causing the loss of over 500 seamen.

The Japanese submarine fleet in the Pacific did not present the same formidable threat to the U.S. merchant fleet as the Germans did in the Atlantic. Nevertheless, during the first few months of the war the threat of attacks by the Japanese created a great deal of apprehension on the U.S. West Coast. Merchant ships spotted a number of enemy submarines along that coast in the first couple of months after the war began. Japanese subs sank eight ships during December 1941 and attacked a number of others without sinking them. The tankers Agriworld and H.M. Storey, sailing along the West Coast, managed to escape without major damage. A unique incident occurred when a lone Japanese sub surfaced and shelled oil fields near Santa Barbara, California, causing little damage.

Not all ships at sea in the Pacific in December 1941 were as fortunate. The Japanese sank the Matson freighter Lahaina on December 10 and its sister ship Manina five days later. The Lykes Lines Prusa suffered the same fate on the 19th. The following day, the tanker Emidio sustained a direct hit to its engine room while sailing north of San Francisco, resulting in its sinking and the death of a number of its crewmen.

The War Shipping Administration

Initially, the United States was ill equipped to fight a two-ocean war. The loss of warships at Pearl Harbor seriously crippled the U.S. Navy’s ability to respond to the Axis threat. The merchant fleet itself also was handicapped by the serious losses inflicted upon it. The remainder of the merchant fleet consisted mostly of old vessels well beyond their prime. Hog Islanders, a type of cargo ship constructed at the end of World War I, represented a disproportionate number of ships available for the tasks ahead. Further complicating the task was the fact that when the war commenced merchant shipping had to sail unarmed and proved to be an easy target for the enemy.

Skilled personnel to serve the planned expansion of the fleet were in short supply. Many merchant marine officers had joined the Navy as that organization rebuilt following the December 7 attack, thus robbing the merchant service of many of its experienced sailors. It became necessary for the U.S. government to launch a high-priority program to build ships and to train seamen. The government established a new organization, the War Shipping Administration, to oversee this critical problem.

The WSA also ordered the building of some 3,700 ships in the course of the war. Most of these were the so-called Liberty ships—10,000-ton cargo vessels powered by reciprocating steam engines and capable of a top speed of about 11 knots. American industry began to turn out these ships at a phenomenal rate although faulty construction of the all welded hulls of the new design caused a number of them to break up in bad weather. Corrections in welding techniques ultimately solved the problem as the war progressed.

Toward the end of the war, American shipyards began turning out the Victory ship to replace the Liberty. The Victory had a top speed of 17 knots and used turbine propulsion engines to replace the less powerful steam plant used to drive the Liberty. The WSA also ordered the construction of a large number of tankers as well as some ships designed strictly for the transportation of personnel.

The staffing necessary to man the new vessels presented a critical problem for the WSA. The government established maritime schools on both coasts to train novice seamen for work in the deck, engine, and stewards’ departments. The average cargo ship required a crew of approximately 45 seamen. In addition, the Navy put two dozen or so gunners, signalmen, and radio operators aboard each merchant ship to provide protection from enemy aircraft and submarines. The average merchant ship carried 10 20mm cannon, a 3-inch antiaircraft gun forward, and a 5-inch antiaircraft gun aft. Merchant seamen acted as loaders for the Navy crews.

Five state maritime academies established in California, Maine, Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania prior to the war furnished officers for the expanded Merchant Marine program. The federal government also instituted a cadet program to train officers through courses set up both on land and at sea. This program ultimately resulted in the establishment of the United States Merchant Marine Academy, an institution similar to the Army’s West Point, the Navy’s Annapolis, and the Coast Guard Academy at New London, Connecticut.

Second Phase: Japanese Submarines Hunting Merchant Marines

In 1942, the United States military undertook its island-hopping campaign across the Pacific, reversing the tide of Japanese naval victories and initiating the long trek toward the Japanese home islands with the invasion of Guadalcanal in the Solomons chain.

The Navy’s Central Pacific Command, under Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, began amphibious assaults on Japanese strongholds in the Gilbert, Marshall, and Mariana Island groups, while the South Pacific Command, under General Douglas MacArthur, began to move through the Solomons and New Guinea toward the Philippines. Both of these commands demanded heavy logistical support from the distant United States.

A steady run of merchant ships began lengthy voyages from the continental United States to these far-flung Pacific outposts. A supply trip from San Francisco or Los Angeles to Australia or New Guinea involved a run of more than 12,000 miles. Virtually all of the war material required by General MacArthur’s forces had to be shipped over that distance. For the slow Liberty ships this meant a month or more at sea, often traveling through enemy-infested waters.

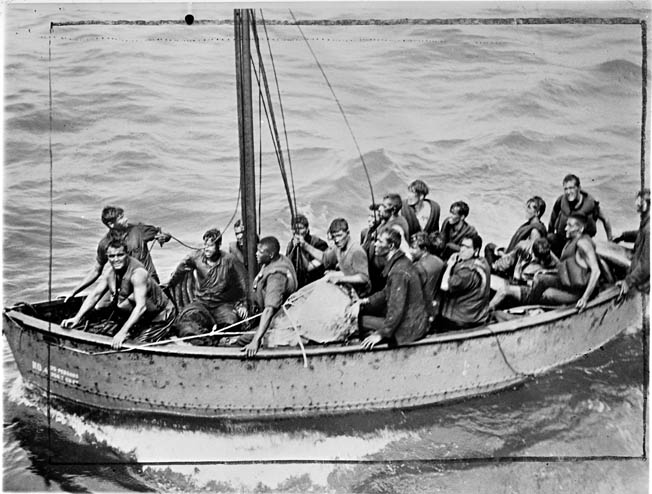

The Japanese did not pursue the same degree of aggressive submarine warfare practiced by the German Navy. The Japanese often used submarines to supply their far-flung island garrisons. However, when the Japanese did sink an Allied vessel the attacking sub would often surface and attempt to kill all of the survivors. After sinking the supply vessel John A. Johnson in October 1944, a Japanese submarine attempted to ram the ship’s surviving lifeboat and raft. It then surfaced and opened up with small arms fire on the survivors in the water. Some 35 merchant seamen and their Navy shipmates survived the onslaught and were rescued the following morning by the patrol yacht USS Argus, which had been alerted by a Pan American Airways plane flying overhead.

During most of the war in the Pacific the majority of the merchant ships managed to complete their runs successfully. These vessels often spent weeks, even months, on lengthy runs to myriad island bases that depended on them for everything from food, arms, and ammunition to mail from home. Most ships sailed in convoys as they neared the active fighting areas, although some of the newer vessels, the Victory and the C ships, sailed alone counting on their speed to outrun the enemy.

Third Phase: Kamikaze Attacks

Prior to the invasion of the Philippines in the autumn of 1944, Japanese submarine attacks against U.S. merchant ships were sporadic. With the American invasion fleet moving toward the Philippine island of Leyte in October, the Japanese naval high command made a fateful decision. Admiral Takijiro Ohnishi, commander of the First Air Fleet, instituted a plan for the crashing of Japanese aircraft into American ships accompanying the invasion of the island.

Ohnishi named this new fighting unit the Special Attack Corps, but it soon came to be known as the kamikaze, or Divine Wind. Overall Japanese strategy involved the use of three methods of suicide attack: the crashing of bomb-laden planes directly into enemy ships; the delivery of a manned rocket-propelled suicide missile, the Ohka, released from a bomber above the target; and the kaiten, a one-man midget suicide submarine carried by a mother sub and directed like a torpedo against an enemy vessel. In practice, however, only the kamikaze proved effective.

The original targets of the kamikaze were American aircraft carriers in order to reduce their overwhelming numbers in combat areas. However, in the ensuing raids Japanese suicide pilots often aimed their planes at any targets that presented themselves.

Despite the Japanese defensive preparations, the American forces landed at Leyte on October 20, 1944. A total of 108 merchant ships participated in the action, a number of them moving into San Pedro Bay to begin unloading men and supplies. On October 24, the Japanese began their waves of kamikaze attacks on American shipping. Some 20 merchant vessels were already in the process of unloading approximately 500,000 tons of food and supplies as well as 30,000 soldiers.

Although the Japanese conducted a series of desperate raids on the anchored ships, the merchant vessels successfully resisted the attempts by the kamikazes to destroy them. Many suffered substantial damage but still managed to inflict heavy losses on the attackers. The merchant ships were credited with shooting down 100 enemy aircraft during the 10 weeks following the Leyte landings. Unfortunately, a substantial number of Navy and Merchant Marine personnel were killed or wounded in the attacks along with a large number of the Army troops that had not yet disembarked for the shore.

As the liberation of the Philippines continued, merchant vessels came under even more intense attacks. In late December 1944, during the invasion of the island of Mindoro, a kamikaze dove into the Liberty ship John Burke. Loaded to the gunwales with ammunition, the vessel exploded, killing all the Merchant Marine and Navy sailors aboard. When the convoy reached Magrin Bay, Mindoro, the Liberty ship Lewis L. Dyche, also loaded with ammunition, suffered the same fate with the loss of its entire complement of personnel. In the same convoy, the Francisco Morazan managed to fight off numerous kamikazes, shooting down six attackers in the process. At twilight, the Hobart Baker became the day’s final victim. Loaded with steel airstrip landing mats, it sank to the bottom of the anchorage after being hit amidships by a kamikaze.

10 Japanese Air Offensives

During the conquest of Okinawa, an island in the Ryukyu group some 350 miles southwest of the home islands, more than 1,600 Allied ships operated off the island in the spring of 1945. Included in the strike force were 170 merchant vessels carrying ammunition, food, fuel, and other general supplies. Over 450,000 men participated in this campaign, 184,000 of whom went ashore for ground fighting. The balance of the force lay at anchor at Hagushi Bay on the west coast of the island and at Buckner Bay on its eastern shore.

In the course of the 87-day campaign, the Japanese launched 10 separate air offensives consisting of 1,465 planes against American shipping off Okinawa’s coast. The Japanese succeeded in sinking 36 ships and damaging an additional 371. The Japanese lost more than 1,900 planes during the campaign.

The merchant ships Hobbs Victory and Logan Victory were among the vessels lost in the anchorage off Hagushi Bay. Loaded with critical ammunition, their destruction resulted in a temporary shortage of phosphorous and 81mm mortar rounds. Replacement for this critical ammunition had to be flown in from the Marianas. Another merchant vessel, Canada Victory, caught by surprise after sundown on April 27, was also sunk in the kamikaze attacks. A Japanese pilot approached unseen and crashed his plane into the mast behind the midships housing, which exploded and ignited a fire that could not be controlled. In addition to these three vessels, an additional dozen or so merchant ships sustained substantial damage.

When the Japanese on Okinawa finally surrendered on June 21, the island became the staging area for the impending invasion of the Japanese homeland. Hundreds of ships arrived with troops and supplies in preparation for the attack. Senior U.S. commanders anticipated heavy losses during an invasion of Japan. Merchant ships would be especially vulnerable to attack once they were clustered in the waters surrounding the islands and attempted to offload their cargoes. However, the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought an end to the war in the Pacific without an invasion of the home islands.

6,830 Merchant Seamen Killed

The United States had about 55,000 merchant seamen in 1941. Many were old timers who could not continue to sail, faced with the rigors of war and its accompanying strains. The government found itself hard pressed to keep up with the demand for seamen in the rapidly expanding wartime merchant fleet. The government training schools accepted men and boys over and under draft age as well as those rejected by the Selective Service System, providing they had the physical capacity to handle the work. The need was so great that some 15-year-old boys were accepted. By war’s end, the Merchant Marine manpower pool had reached 215,000.

In the course of the war 6,830 merchant seamen were killed, more than 11,000 were wounded, and more than 600 became prisoners of the Japanese. The casualty rate of the United States Merchant Marine was among the highest of any service.

A total of 731 American merchant ships were lost to enemy action during the war. Forty-three of these were lost in the Pacific campaigns. Many more merchant vessels were seriously damaged. Without question, the U.S. Merchant Marine had met its goals in delivering the men, equipment, and supplies needed to defeat the Japanese Empire.

Said General MacArthur at the conclusion of the Pacific campaign: “They have brought us our lifeblood and paid for it with some of their own. I saw them bombed off the Philippines and in New Guinea. When it was humanly possible, when their ships were not blown out from under them by bombs and torpedoes, they delivered their cargoes to us. In war it is performance that counts.”

My step dad was a Merchant Marine and served in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. He told about his War service

My dad was a 2nd engineer, merchant marine officer serving on Liberty ships in Pacific, Atlantic and Med/Nor. Africa theaters. Also pre-WWII as seaman on commerce trips to China, and Japan ironically. He served on the New Guinea-Philippine shuttle runs, amongst others. Was at port in Tacloban during the epic Battle of Leyte Gulf nearby.

His stories included several close calls from torpedo attacks, low-level Japanese bomber and high-level German bomber attacks, both under-way in convoys and anchored in foreign ports. Other war-related stories: shore-leave (stepping-over dead bodies in Chinese cities), a near fire-fight aboard a PT boat at night. Other incidents: storm related, cultural/urban mishaps, wildlife encounters.