By Brooke C. Stoddard

Steaming through the summer Mediterranean night, the world having gone sour in two awful months, British Vice Admiral Sir James Somerville read the message just sent to him from London: “You are charged with one of the most disagreeable and difficult tasks that a British Admiral has ever been faced with, but we have complete confidence in you and rely on you to carry it out relentlessly.” The message was received with a heavier heart than the sender—Prime Minister Winston Churchill—surmised. Somerville not only found the task highly offensive, he was also opposed to it. Nevertheless, there it was. Duty. Orders. Had to be obeyed.

It was the night of July 2, 1940. In May Hitler had overrun the Low Countries and driven the British Army to the English Channel. In June German armies had completed the rout of the British, pressing them out to sea at Dunkirk, and then swept down to finish off the French. Winston Churchill, practically a lone voice in the 1930s against the danger of Hitlerism, had been appointed prime minister on May 10, yet had presided over little except disaster, and knew it. “Wars are not won with evacuations,” he had said of the Dunkirk retreat, but even in those dark hours believed the French armies would stiffen and halt the Wehrmacht short of Paris, or at least along some line to which the British could return. He saw this new war as a child of the one that ended in 1918, the French and the British again holding up short the German soldiers and slowly pressing them back to their borders. Indeed, France and Britain each had made a pledge to the other not to make a separate peace with Germany. During the disasters on the Continent Churchill made several flights to France—to assess the situation, to rally the flagging leaders, and to assure the French that Britain would stand by them for as long as it took to ensure victory for the freedom-loving democracies over Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.

France Bargains with Hitler

Churchill believed—and expected—France would fight on, if need be; to give ground as slowly as possible, if necessary, through the streets of Paris, then south of Paris, even battling in a dogged retreat all the way to the Mediterranean, and not even stopping then but carrying on the fight from North Africa. By early June, however, there was real speculation that France would break its pledge against a separate peace and bargain with Germany. This would have grave effects on Britain. Rather than slowly giving ground and helping to wear down the Germans, the French armies would be out of the fight. Resistance in occupied areas would be minimized. The Germans and Italians would be able to turn their full force against their one remaining foe—Great Britain.

But these, it might be said, were the least of the possible consequences. If France dropped out of the war, its powerful Navy might well fall to the Germans. This had to be viewed with the utmost gravity. As Churchill well knew—he had been First Lord of the Admiralty in 1911-1915 and again in 1939-1940—Britain could only survive so long as it retained a general command of the sea. Losing that, it could not import food, it could not order and offload arms from America, and it could not communicate with its Commonwealth countries. Indeed, without a general command of the sea around its island, it could not stave off invasion by Werhmacht divisions and armor, which would make quick work of a British Army that had been forced to abandon nearly all its heavy equipment during its evacuation from Dunkirk.

A great deal of the British Navy would be needed to protect the North Atlantic sea lanes and the Channel. The supposition from the outbreak of the war in September 1939 was that the French fleet could protect the Mediterranean and adjoining portions of the Atlantic, countering the weight of the Italian Navy should it come in on the German side. This Italy did on June 10, as the French government was preparing to flee Paris. The Italian Navy was formidable but built to operate in the Mediterranean only; the French fleet was more than a match. Indeed, the French fleet was reckoned the fourth largest in the world. The brand-new Strasbourg and Dunkerque were deliberately designed to be more powerful than the German battle cruisers Gneisenau and Scharnhorst. Almost finished was the Richelieu, believed by Britain’s First Sea Lord Admiral Sir Dudley Pound to be the world’s most powerful ship when it could be completely fitted.

All Hope Rested on the British Royal Navy

But should France declare a cease-fire and begin talks with the Nazis, the blow to Britain would be greater than having been pushed off the Continent at Dunkirk. Should the French surrender their fleet to the Germans and Italians, and should the Germans and Italians put the French ships to their own use, the combined German-Italian-French fleet (as estimated by U.S. Navy Intelligence officers at the time) would be half again as strong as the British Navy. This would not only deny to the British the Mediterranean—their conduit to the Middle East and their shortest passage to India—but also would threaten their control of the oceans around their island nation. Should the Royal Navy be overcome, all was lost for Britain.

On June13 Churchill made his last and desperate trip to the fleeing French government, then in Tours. He argued passionately against a French collapse and separate peace. There was still hope, but he specifically approached the commander of the French Navy, Admiral Jean François Darlan. “You must never let them get the French fleet,” he told the Frenchman. Darlan was equally firm. He promised the British prime minister that the French Navy would never surrender to German authority.

But each day brought new tragedy; circumstances changed by the hour and France looked increasingly defeated, in spirit as well as in the field. Still, the British worked to keep them in the fight. Indeed, when France’s hour of agony was at its height, Churchill entertained and then proposed the notion that the two nations combine. This was meant to boost the position of French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud, who wanted to keep his country in the war but who was facing terrific opposition from politicians ready to acquiesce to Germany. Churchill’s proposition was that “France and Great Britain shall no longer be two nations but one Franco-British Union, both peoples combining in a single citizenship and the Union having single departments of defense.” If this could be accomplished—and a meeting was set up with French politicians to do just that—then the French fleet would be under the command of the Union and would fight with the British under Union orders. France would not be out of the war and its navy would not be in danger of falling intact to Germany.

But by then France was too broken to be fixed. Power was shifting to those who wanted release from their pledge against a separate peace. Gone was the vision that this second war —like the one that had ended 21 years before— would be fought out on a line in France until Germans could be pressed back. All British grip on the Continent was gone; the French armies were gone. That was bad enough, but what was worse, the French fleet might go as well.

On June 16 Great Britain agreed to release France from its pledge of no separate peace, but with an important condition: “provided, but only provided, that the French Fleet is sailed forthwith to British harbours.”

“Such an Act Would Scarify Their Names for a Thousand Years of History.”

On the 17th Churchill wired the new government of France: “I wish to repeat to you my profound conviction that [you] will not injure their ally [Great Britain] by delivering over to the enemy the fine French fleet. Such an act would scarify their names for a thousand years of history.” In these critical days, the French ships could have put themselves out of reach of Germany, and some did. Some were already in British harbors, or in the great British fleet harbor of Alexandria, Egypt. Some sailed from southern France to West and North Africa. But Admiral Darlan, formerly head of the French Navy, was now a part of the new defeatist government, its minister of marine. He was resolved to keep the French ships out of German hands, but he made little substantive effort to move them. Indeed, as part of the government, he was bound ever more closely to the terms of the German-French armistice.

And these terms, when they were made public, greatly troubled Britain. Article 8 of the armistice, concerning the French fleet, read that the French ships “shall be collected in ports to be specified and there demobilized and disarmed under German or Italian control.” Here were British fears confirmed. If the ships were under German or Italian control, who could not say the Germans and Italians might change their minds about demobilizing and disarming them? They might suddenly seize them, arm them, man them, and sail them against the British, who certainly had ample evidence that Hitler was not a man who kept his word. Or Germany could say that in some manner France had violated armistice terms, nullifying the written agreements and allowing Germans to swoop down on the ships.

There was also a clause that allowed the Germans to use ships as “necessary for coast surveillance and mine-sweeping.” Who knew how the Germans might interpret that, or use large portions of the French fleet and thus free up their own vessels? The British did not doubt Darlan’s word about never surrendering the French ships to their enemies, but they did doubt whether he had the means of forever making it good. Thus they viewed the French fleet as a very large weapon idling in a kind of no-man’s land.

If the French warships could not be converted to British use or somehow neutralized peaceably, they must be destroyed. Churchill, the former First Lord of the Admiralty, was adamant. He debated with his military advisers, won them over, and set in motion operations to eliminate—by violence if need be—the threat of the French ships.

Looking back in 1949, Churchill reported in his memoirs: “The War Cabinet never hesitated. Those Ministers who, the week before, had given their whole hearts to France and offered common nationhood resolved that all necessary measures should be taken. This was a hateful decision, the most unnatural and painful in which I have ever been concerned. It recalled the episode of the destruction of the Danish Fleet in Copenhagen Harbour by Nelson in 1801…. It was a Greek tragedy. But no act was ever more necessary for the life of Britain and for all that depended upon it.”

Scattering of the French Fleet

Despite Churchill’s later statements, he did meet early opposition among his counselors. Some of his military advisers in London were opposed to the use of ultimatums and force. Commander of Britain’s Mediterranean fleet, Sir Andrew Cunningham (commanding from Alexandria), and Somerville at Gibraltar were opposed. But Churchill took some solace in the fact that Franklin Roosevelt, a former assistant secretary of the U.S. Navy, saw the terrible necessity for strident action. Both Roosevelt’s Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Harold Stark were so concerned about a strong German Navy cruising the Atlantic that they considered transferring a good portion of the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor to Atlantic waters.

On June 22, when the French agreed to their armistice with the Germans, the French fleet was scattered. In British ports were the old battleships Paris and Courbet, as well as a number of large destroyers, and seven submarines, including the Surcouf, which was the world’s largest. At Casablanca and Dakar (French West Africa) lay the new, though not yet complete, powerful battleships Jean Bart and Richelieu. Other French ships were anchored at Alexandria, along with the British Mediterranean fleet.

The largest squadron was at Mers el Kébir just northwest of Oran, Algeria. Tied up by the stern at the long jetty were the older battleships Bretagne and Provence, but also the modern, fast battle cruisers Dunkerque and Strasbourg. There was also a seaplane carrier and six large destroyers. In Oran harbor lay seven more destroyers and four submarines.

Churchill and his War Cabinet would shortly see that the French were doing little to move their ships out of harm’s way and thus they set in motion Operation Catapult, the scheme to win over or neutralize the French ships, especially at Mers-el-Kébir. Secrecy and surprise were to be essential; much was to be done in different parts of two continents on the same day or very close together. Orders were sent out to Cunningham in Alexandria and Somerville, who was to lead a squadron—code-named Force H—from Gibraltar to Mers-el-Kébir.

Meanwhile, Darlan was signaling his own fleet. On the 26th he sent a message that stated in part: “Demobilized ships are to stay French, under French flag, with reduced French crews. Secret precautions for sabotage are to be made in order that any enemy or ex-ally [French captains would know this referred to Great Britain] seizing a vessel by force may not be able to make use of it…. In no case obey the orders of a foreign admiralty.” In a communiqué two days later he wrote: “To respond to outside interests would lead our territory into becoming a German province. Our former allies are not to be listened to.” Darlan not only believed that if the French fleet submitted to Britain, then Germany would denounce the armistice and occupy all of his country, but he also probably believed that Britain would soon be defeated. In that case, what was the point in having the French fleet be defeated with them?—if the French ships held out, the French Navy could later say it was the one fighting force against the Axis that was not beaten in battle.

Both the British and the French had some cause for feeling somewhat betrayed. The British believed the French had broken their word, first about not contemplating a separate peace and then doing so, ignoring the one provision laid on by the British—moving their fleet to British-controlled ports. For their part, the French felt bitter over what they believed to be inadequate aid from the British in thwarting defeat, especially in not sending more airplanes to France to slow Werhmacht advances (the British position being that they needed these airplanes in case Germany attempted an invasion of England).

“If French Will Not Accept Any of Your Alternatives They Are to be Destroyed.”

Somerville did not like Catapult in the least. After conferring with Captain Cedric S. Holland, former British naval attaché in Paris and the person most acquainted and friendly with high-ranking French naval officials, he telegraphed London: “After talk with Holland and others Vice-Admiral Force H is impressed with the view that the use of force should be avoided at all costs. Holland considers offensive action on our part would alienate all French everywhere they are.”

Several hours later the Admiralty signaled back: “Firm intention of H.M.G. [His Majesty’s government] that if French will not accept any of your alternatives they [the ships] are to be destroyed.” Under this cloud, Somerville sailed overnight from Gibraltar to Mers-el-Kébir.

As the sun rose on July 3, Somerville and his Force H arrived off their destination. Force H was a powerful squadron comprising Somerville’s flagship the HMS Hood, possibly the most powerful ship then afloat; battleships Valiant and Resolution; aircraft carrier Ark Royal; two cruisers; and 11 destroyers. His orders were explicit: He was to deliver to Vice-Adm. Marcel Bruno Gensoul the following terms, spelled out—after an explanatory preamble—thus:

“(1) Sail with us and continue to fight for victory against the Germans and Italians.

“(2) Sail with reduced crews under our control to a British port. The reduced crews will be repatriated…. We will restore your ships to France at the conclusion of the war, or pay full compensation if they are damaged ….

“(3) Alternately, if you feel bound to stipulate that your ships should not be used against Germans or Italians, since this would break the Armistice, then sail them with us with reduced crews to some French port in the West Indies … where they will be demilitarized by us to our satisfaction, or perhaps be entrusted to the United States of America….

“If you refuse these fair offers, I must with profound regret require you to sink your ships within six hours. Finally, failing the above, I have the orders of His Majesty’s Government to use whatever force may be necessary to prevent your ships from falling into German or Italian hands.”

Attack a Former Ally?

Somewhat ahead of the main body of Force H, at 6:30 in the morning, HM destroyer Foxhound conveyed Captain Holland, the former naval attaché in Paris, to the harbor entrance to deliver these terms to his friend Admiral Marcel Gensoul. Another good friend of Holland’s, Gensoul’s flag lieutenant, a Lieutenant Dufay, received him. Dufay sped to Gensoul’s flagship Dunkerque for instructions. The French presently spotted the bulk of Force H. Gensoul did not like the smell of this at all; as a proud Frenchman he was not about to be manipulated with ultimatums, especially under the shadow of powerful guns. He had his orders to follow. Gensoul sent Dufay back to Holland with the message that he would not see him. In addition, at 8:47, Gensoul ordered Foxhound to leave the harbor. Holland ordered Foxhound to retire, but took a launch to Dunkerque himself in hopes the admiral would change his mind. He at least managed to have the written version of the British position terms delivered to Gensoul.

Then Holland, Somerville, Pound, and Churchill anxiously awaited Gensoul’s decision. In his memoirs, Churchill reported that “at the Admiralty there was manifest emotion” at the prospect of “open[ing] fire on those who had so lately been our comrades” but that “there was no weakening in the resolve of the War Cabinet.” He remained in the Cabinet Room during the critical hours in contact with the Admiralty.

Between 9:30 and 10 am, Gensoul first sent the following to the French Admiralty: “An English force composed of three battleships, an aircraft carrier, cruisers and destroyers before Oran has sent me an ultimatum: ‘Sink your ships; six-hour time limit, or we will constrain you or do so by force. My reply was: ‘French ships will answer force with force.’” He then ordered his fleet to get up steam and prepare for action. He also sent a message with Dufay to Holland: “The assurances … remain un- changed. In no case, anytime, anywhere, any way, and without further orders from the French Admiralty, will the French ships fall intact into the hands of the Germans or the Italians. Given the form and substance of the veritable ultimatum which has been sent to Admiral Gensoul, the French ships will defend themselves with force.”

Clearly, the message Gensoul signaled to his superiors was grossly and negligently incomplete. He made no mention of the options to join the British, turn over the ships to the British, or have the ships sail to neutral and safe ports. Compounding these misrepresentations was the fact that the French Admiralty was on the move—from Bordeaux to Vichy. Darlan could not be reached immediately and a Rear Admiral LeLuc had to deal with the shocking news from Oran.

LeLuc did not see much room for maneuver. The last messages from Darlan touching on the subject were those to the fleet on June 24 and 26, the former ending with the order: “In no case obey the orders of a foreign admiralty.” LeLuc responded by signaling powerful squadrons in Toulon, France, and in Algiers to prepare for action and steam in reinforcement to Oran. This message was intercepted by the British on the Continent and forwarded to Churchill and Pound.

French Sailors Were Visibly Remorseful

As the morning wore on, the British signaled quite visibly and “in clear” to French ships their offer to welcome the French ships into the British fleet. They had supposed that the French commanders might withhold that information from their sailors but that the sailors, being aware of it, might tip the tide of opinion to the British favor. Indeed, one witness later said that during the time of the negotiations the French sailors seemed to go about their duties with exceptional lethargy and remorse.

At a little after noon Gensoul sent a second message to his admiralty, being somewhat more forthcoming about the British terms: “Initial English ultimatum was: either rally to the English fleet or to destroy the ships within five hours to prevent their falling into German or Italian hands. Have replied: (1) The latter eventuality is not to be envisaged. (2) Shall defend myself with force at the first cannon shot, which will have a result diametrically opposed to that desired by the British Government.”

No new decisions were forthcoming from the French Admiralty. The British Admiralty knew only that the French were sending reinforcements prepared for combat.

Somerville ordered a British plane to drop several mines in the main shipping channel of Mers-el-Kébir, the better to box in the French ships and prevent their escape. This was done, and observed by the French.

At 1:15 pm, with the grace period drawing to a close, Somerville signaled Gensoul to accept one of the British terms by hoisting a white flag, or “if not, I will open fire.” Gensoul signaled Somerville to wait until he had heard again from his superiors.

Somerville then disobeyed his orders. He signaled to Gensoul that he would extend the deadline for two hours, until 3:30. At about this time Gensoul received a message from the French Admiralty to this effect: “Do not demobilize—reinforcements are on the way.”

An Ultimatum for Gensoul

As 3:30 neared, Gensoul signaled that he would receive Captain Holland in person. Somerville was heartened by the news and granted another two-hour extension. Holland boarded the Dunkerque and was ushered to Gensoul’s quarters. The British captain again stressed to Gensoul that his government did not at all doubt Darlan’s word, but that the Germans might be capable of a surprise attack that Darlan, even in his best efforts, could not thwart. Gensoul told him that it would never happen. He promised to use force against any German threat, or if time permitted to evade them by sailing to the West Indies or the United States. In fact, Gensoul was now more riled than before. He bristled at being given what he considered an ultimatum under threat of British guns, and since the mining of the harbor he was even more indignant. Holland stressed how close they were to a peaceful settlement.

But time was drawing close. They could come no closer to an agreement. Gensoul felt he had to remain absolutely true to his orders and to the terms of the armistice. Holland signaled Somerville of the impasse. It was 5 o’clock.

Fifteen minutes earlier Somerville had received a new dispatch from the Admiralty. It read: “Settle matters quickly or you will have reinforcements to deal with.” Somerville knew that this meant menace from both surface ships and submarines. In addition to the French ships preparing to bear down on him the Italian Navy might show up—after all, the British force had been in virtually the same location for 11 hours. He sent a final message to Gensoul: “If none of the British proposals are acceptable by 17:30 BST [British Summer Time], it will be necessary to sink your ships.”

Gensoul handed the message to Holland. Then the French admiral stood up, nodded to the British captain, and walked from the room. Holland was given departing honors as he disembarked Dunkerque. It was 5:25, and he saw the French sailors manning their battle stations. But he noted their lack of hustle and that many seemed to be milling on the upper decks as if they believed they would yet escape violence. The officer of the watch on Bretagne saluted Holland in respect.

Gensoul climbed to the bridge of the Dunkerque and said to an officer, “I have done everything to gain time. Now it is finished.”

The Foxhound cleared the harbor, laying mines as it went.

Open Fire

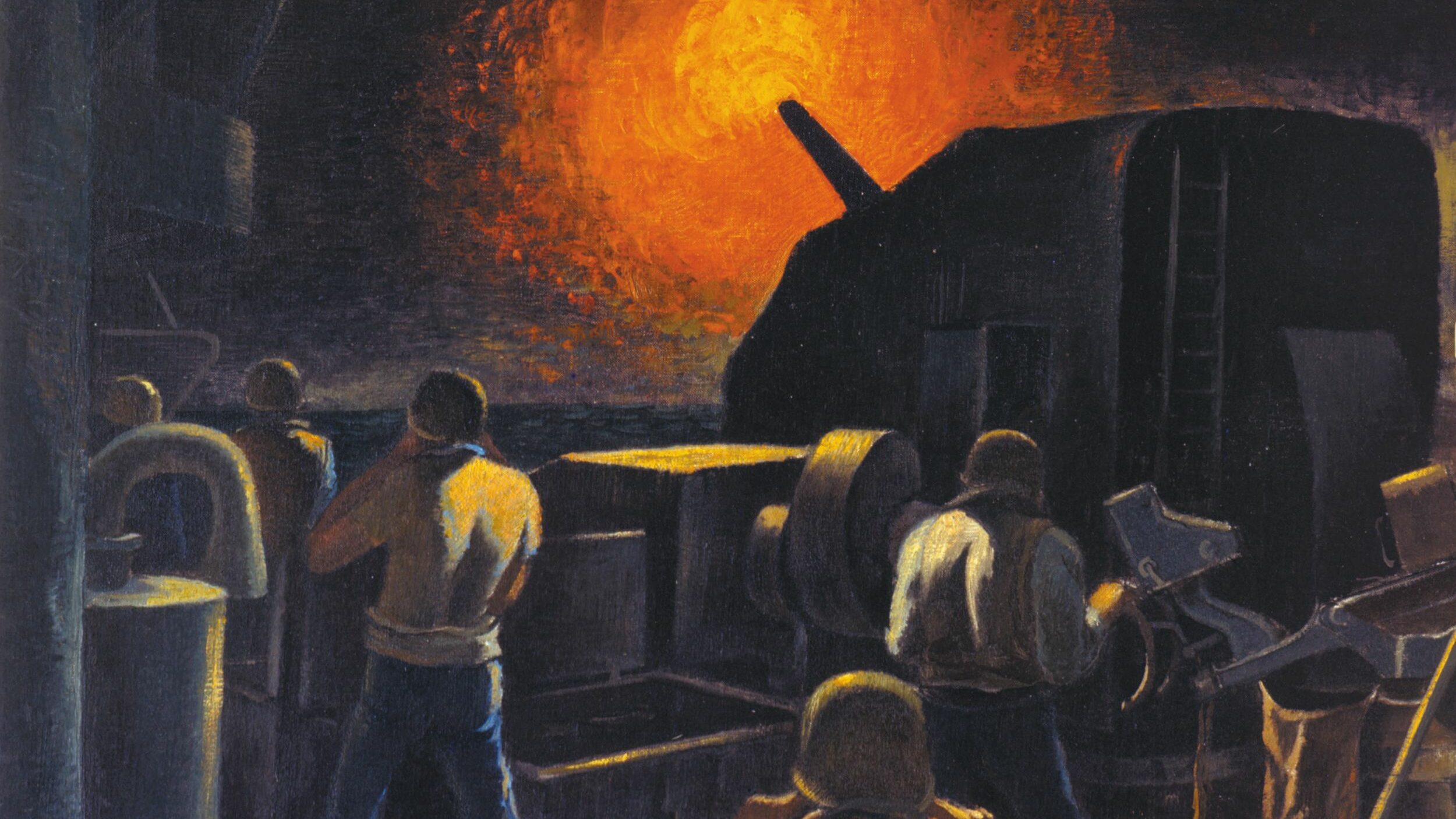

Somerville kept waiting, holding his sights on the French battlewagons, still hoping even to see the white flag that meant his former Allies would meet one of his conditions. But only the French Tricolor flew in the evening air. His deadline came and went. More time passed. At last the cold press of time and duty forced him to action. At 5:55 he gave the order he hated: “Open fire.” The Hood at the head of the British line, 17,500 yards from the French ships and steaming at 17 knots, trembled as its eight 15-inch guns roared.

The French were, of course, sitting ducks. They were lined up with sterns cabled to the jetty, bows pointing toward the land and away from the British battle line. Gensoul ordered fire returned and for his ships to make for the sea. He telegraphed his government: “In action against the British Force.”

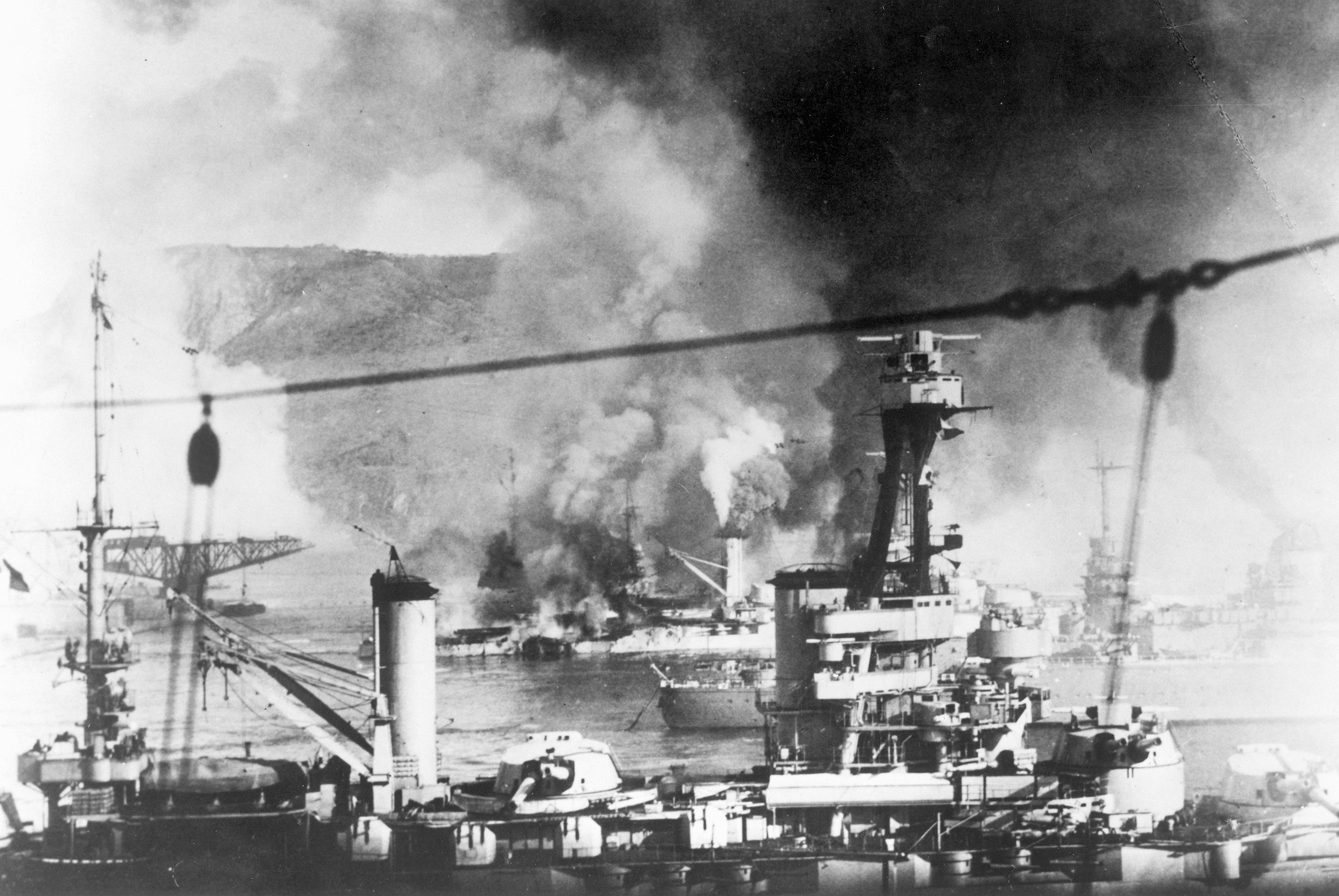

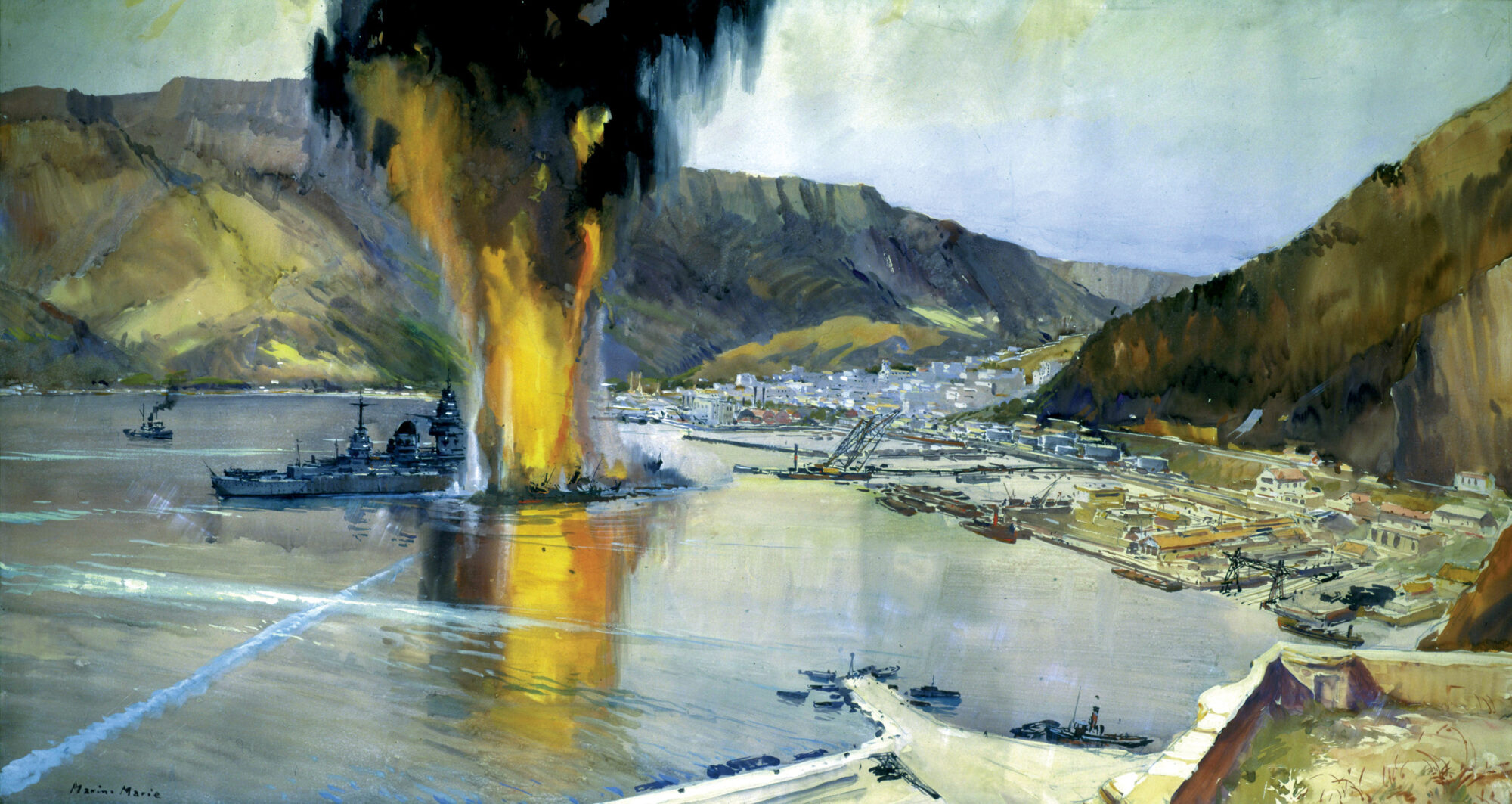

Since the French warships had been raising steam there was haze and smoke over Mers-el- Kébir harbor. This made exact ranging difficult. But the British gunners had the assistance of a Swordfish aircraft launched from the Ark Royal. Observing the bombardment from 7,000 feet it could report the location of the landing shells. The first salvo fell across the seaplane carrier, the Bretagne, and the Strasbourg.

French broadsides sent geysers of seawater up near the British battle line, but their aim was defective owing to smoke around their ships. Moreover, their biggest guns could not bear on the British force—the Dunkerque and Strasbourg’s big guns were forward, pointing away from the open sea. Only the Bretagne and Provence could put their largest guns to use. No British vessels were hit.

The second British salvo hit the Bretagne as she was attempting to cast off. At least one shell reached the after magazines, which exploded in a great mushroom cloud. Soon Bretagne was ablaze. She sank in two minutes, taking 977 French sailors to their deaths. By now the seaplane carrier was also on fire. The Dunkerque was hit four times as she attempted to maneuver. Her electrical system out, her crews turned the gun turrets by hand and fired four salvos at the Hood. But damage to her [Bretagne] was severe, and she beached. Slipping through the harbor, Provence was hit in the stern by a 15-inch shell. Her captain feared she would sink, blocking the channel to others, so he beached her.

After nine minutes of bombardment, Somerville called a respite so the French sailors might leave their ships, which he was convinced they would do once firing began. In this he was wrong. Captain Collinet of the powerful and swift Strasbourg called for full speed and turned for the open sea, and just in time, for a moment later 15-inch shells slammed into her vacated berth. Twisting and turning through the smoke and wreckage she somehow evaded slamming shells and lurking mines then gained speed in the darkening evening outside the harbor. A British plane spotted her, along with five destroyers from the Oran harbor, but Somerville at first dismissed the report.

Hoisting the White Flag

At 6:10 Gensoul signaled Somerville: “All my ships are out of action. I request you cease fire.” Somerville required Gensoul to hoist a white flag. Gensoul did not have one, but improvised with a tan blanket. There was no more firing to or from Mers el Kébir.

But soon Somerville received another report of Strasbourg’s dash out to the northeast. He broke away from land in pursuit. The Strasbourg had a good jump, however, owing to the smoke and the westward position of the British battle line. Somerville ordered a torpedo strike from six Swordfish airplanes. None made a hit, nor was a second attack two hours later successful. The Strasbourg ultimately reached the great French harbor at Toulon unscathed. So did a number of destroyers, and eventually the seaplane carrier. A British submarine sank an auxiliary ship attempting flight.

These actions off the Algerian coast were not the only operations against French ships, planned in secrecy with many far-reaching tentacles. In Portsmouth harbor, England, the British seized French vessels during the night of July 2. In Plymouth, at least one British officer and a French rating were killed in a scuffle to seize the submarine Surcouf. In Alexandria, Egypt, Admiral Cunningham began negotiations with Admiral Godfrey. The next day these talks bore fruit, and the French ships surrendered their breech-blocks to the British. On the 8th, aircraft attacked and severely damaged the Richelieu in Dakar.

The Pétain government, which had set itself up in Vichy on July 1, was furious. It ordered bombing runs by French planes against British Gibraltar, which were carried out. It broke off relations with Great Britain on July 5.

The Aftermath of Mers-el-Kébir

But not all French were so dismayed. Charles de Gaulle, then an armor general and leader of the movement to carry on the fight, but whom the British did not consult in advance about Catapult, was restrained no matter what his personal feelings. In all, more than 1,200 Frenchmen lost their lives during the British attacks on the French ships. Families of slain sailors were bereaved and shattered. But two peasant families at least, each of whom had lost sons, requested that the Union Jack as well as the French Tricolor lie upon their loved ones’ coffins.

On July 4 Churchill reported to Parliament. He wrote in his memoirs (1949) that, following his remarks on this day that for the first time, he felt the whole approval of Parliament behind him, not merely its Labour members. He then wrote that “the elimination of the French Navy as an important factor almost at a single stroke by violent action produced a profound impression in every country. Here was this Britain which so many had counted down and out, which strangers had supposed to be quivering on the brink of surrender to the mighty power arrayed against her, striking ruthlessly at her dearest friends of yesterday and securing for a while to herself the undisputed command of the sea. It was made plain that the British War Cabinet feared nothing and would stop at nothing.”

Indeed, the attack at Mers-el-Kébir was a turning point of sorts. The booms of the bombardment soon quieted around the harbor, but the shock waves traveled far and wide. Franco in nearby Spain must have been impressed; he never did enter the war on the side of his Fascist brethren. More importantly, Franklin Roosevelt across the Atlantic, and a former assistant secretary of the Navy, was deeply impressed with this show of British determination. Previously there was much talk in Washington about withholding arms and ships for Britain under the theory that in the likely event of capitulation of the British, these same arms and ships would be turned against Americans. After Mers-el-Kébir, the tenor changed. Very shortly, Roosevelt agreed to send to Britain 50 U.S. destroyers, more confident that Britain had the will to persevere, even to triumph.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments