By Colonel Robert Barr Smith

The English officer studied the Burmese river and its surroundings. The area seemed quiet, for the moment peaceful. And so the officer gave his men permission to take a brief swim in one of the little coves along the river bank. The Englishman stripped down himself, relishing the thought of the cool water. Even so, experienced soldier that he was, he did not takeoff the one critical item he could not put back on in seconds; his boots. Otherwise naked and weaponless, he wandered into the next small cove for a brief moment of privacy … and came face to face with a Japanese officer, as naked as he was.

The two men eyed one another. Both were professionals. Both knew the other could not be alone. Neither knew the strength of his enemy’s unit. Either one of them could call for help, but ran the risk of involving his own men in a hopeless fight with a far superior force. And so, in silence, the Englishman and the Japanese grappled hand-to-hand in the waist-deep water of the cove.

A Fight to the Death

The Japanese was trained in martial arts. The British officer was taller and stronger. Neither man could move easily in the water. The Japanese clawed for the Englishman’s eyes, and the Englishman shoved his face against his enemy’s chest to save his sight. Panting, they wrestled in silence, struggling to keep their footing on the slippery river bed.

At last the Englishman got a firm grip on the Japanese officer’s right wrist and twisted it behind him. Setting his feet, his boots giving him a secure footing, he slowly forced the squirming man’s head under water and held him there. The Japanese struck out in desperation, lashing out with both feet and his free arm, but the Englishman only tightened his hold, forcing his thrashing enemy deeper until the body beneath him went limp and a cloud of bubbles burst to the surface.

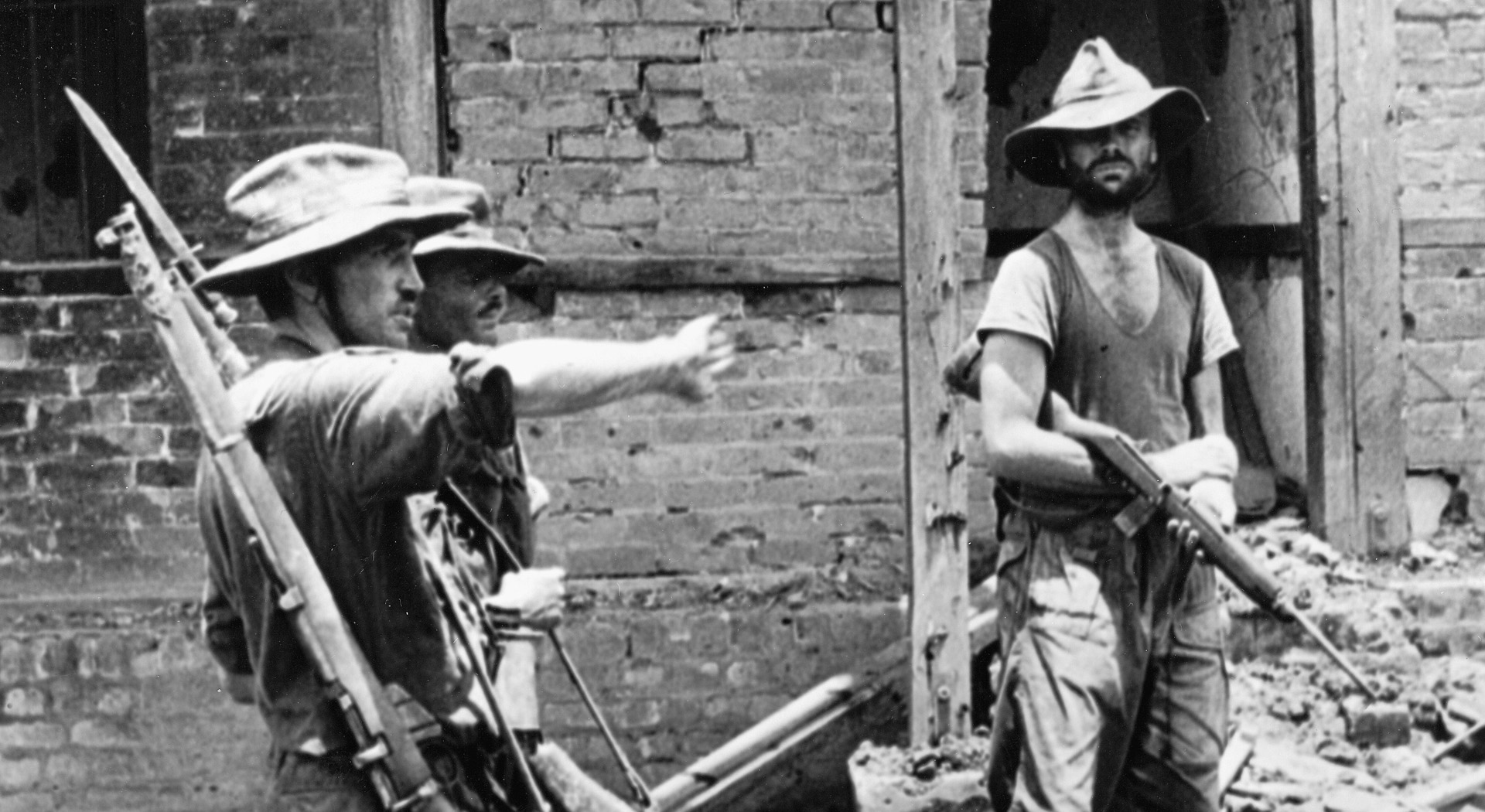

Panting, feeling sick, the Englishman watched his enemy’s corpse drift slowly away from him then trudged out of the water and hurried back to his men. Most of them were out of the water by now, joking and laughing together, but their smiles faded as they saw their commander’s grim face and battered body. “Japs,” the Englishman gasped, “in the next cove but one. I killed their officer. They don’t know we’re here but they will do in a moment. Get after them now.”

His men reacted instantly, snatching up their weapons and moving quickly along the river bank to the cove where the Japanese officer’s 20 soldiers were still enjoying a rare moment of rest. That moment was their last. In a blaze of point-blank gunfire, the Englishman’s dozen soldiers cut down the astonished Japanese, leaving nothing but naked corpses in the turgid, bloody water of the river cove.

Unforgiving, Merciless, Implacable Burma

That was war in Burma—unforgiving, merciless, implacable. This was the war this English officer fought every day. He was called Mike Calvert.

Burma was a hideous place to fight, a nightmare world haunted by fatal and debilitating disease, an unforgiving land of exhausting hills and jungle, of swarms of leeches, clouds of mosquitoes, and armies of other voracious insects, of rot and fungus and broad, treacherous rivers and wounds that would not heal.

The long, long road from the mountains along the Indian border, south through Mandalay, and on to the sea was soaked with blood and sweat, a monument to the agony of lost youth and wasted years. At the end of a series of long and terrible campaigns, the British and Indian soldiers smashed their Japanese enemies and drove the survivors in disorganized rout from the last inch of Burmese soil. Although the roadsides and fields and hills and jungle were littered with more than 100,000 Japanese dead, the victory had been won at terrible cost in death and suffering. It took a special kind of man to fight in the bowels of Burma and survive, and in the end to win.

Calvert’s Special Dislike of the Japanese

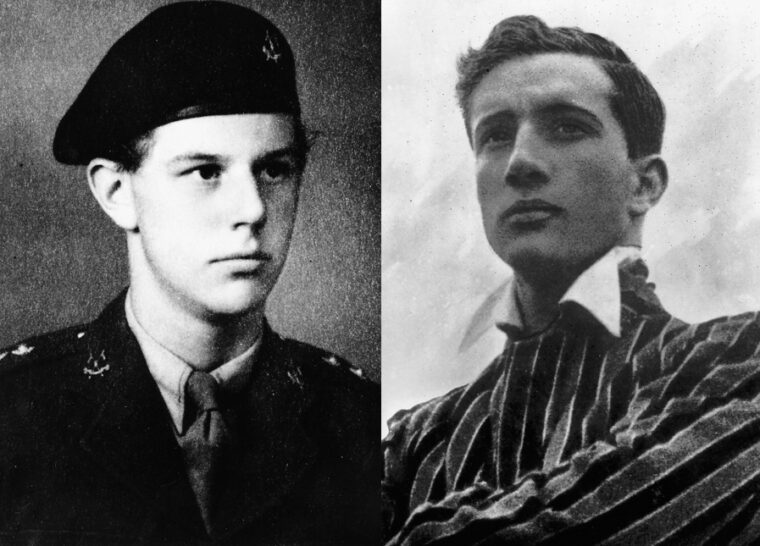

Michael Calvert was that sort of man. He was, in the purest sense, a warrior. Calvert was a regular, one of four soldier brothers, a Royal Engineer who entered the British Army well before the first shots of World War II were fired. He knew the Japanese for what they were, for he had served in Hong Kong and Shanghai during the unprovoked Japanese aggression against China in the late 1930s. In a 1994 interview in London, he told this author that he found the Japanese “infuriating … [they] were demeaning … white people, especially the British. You know, they’d make a woman strip naked on the Peiping railroad platform, that sort of thing … and it was this that made me feel ‘I must beat these bastards.’”

Calvert himself “took to wearing underpants with a rising sun on the rear, just in case I got captured and stripped.” When this author suggested that was possibly not the wisest course of action, Calvert agreed that it was not, but “that was the way I felt about those people.” After all the years, there was still a fierce light in his eyes when he said that, and for a moment you could see the young warrior, the uncompromising soldier of the Burma days.

Calvert also spoke with people fleeing to Shanghai after the orgy of atrocity called the Rape of Nanking. He had heard firsthand accounts of Japanese cruelty and sadism and arrogance from those who had seen the horrors of Nanking. He knew his enemy well, but he would have to wait to have his chance to “beat these bastards.” When that chance did come, he would make the most of it.

Service in Europe and Australia

First, however, Calvert spent time serving elsewhere. During the ill-fated Norwegian campaign of 1940, he put his engineering skills to good use, blowing up whatever might be of use to the German invaders. An order to him by Maj. Gen. Bernard Paget as the British Expeditionary Force fell back still exists: “Dear Calvert. I am trying to get the rest of the army out of this place but I am having a difficult time…. If the Germans arrive before this do your demolitions, but if possible try and hold them off until we get through.… I must leave it to you. Best of luck.”

After the Nazi blitzkrieg of 1940 drove France into abject surrender and Britain off the Continent, Calvert spent some time rigging demolition charges in vulnerable spots along the Channel coast, preparing to destroy any structure that might be of use to a German invader. Along the way, he recalled, he wreaked some unintended destruction on a long pier when a seagull landed on top of one of his infernal devices. The debris from the explosion detonated another charge, and so on, until the entire pier was a hopeless wreck—with no German within 20 miles.

Calvert served in Australia as well, teaching Australian troops how to efficiently blow things up, and in time ended up in Burma, teaching at the Mamyo Bush Warfare School.

Calvert Meets Wingate

His remarkable career thereafter began with an odd meeting with an extraordinary man, the messianic Old Testament warrior Orde Wingate. Prior to the war, Wingate had won renown in Palestine, where he organized the Night Squads, irregular units of Jewish colonists and British soldiers that raised havoc with the Arab guerrillas, who were attacking Jewish settlements. He later served in Abyssinia, brilliantly commanding an odd assortment of troops he named Gideon Force against the Italians. Wingate knew a good deal about irregular warfare, and he was in Burma to put his knowledge into practice.

This brilliant, able, abrasive man, now a major general, was presciently selected by General Archibald Wavell to attempt a very special task, and there he was to meet Calvert, a soldier after his own heart. It happened like this. In 1941 Calvert returned to his office at the Bush Warfare School to find a strange officer sitting in his chair. “Who,” asked Calvert reasonably, “are you? And you’re in my chair.”

“I’m Wingate,” the man replied, and Calvert learned that his new acquaintance had been picked by General Wavell to take command of all special operations in Burma. Wingate’s theories of deep penetration behind enemy lines immediately won Calvert’s allegiance. Back in 1940, Calvert had written a paper on small force operations “behind the enemy lines supplied and supported by air.” That notion, somewhat radical for the time, fitted Wingate’s ideas about jungle war exactly. For Calvert, who admired Wingate and served him well, Wingate was “to a certain extent … a hero looking for a cause. And far-seeing people like Wavell knew where to put these people, where they’d do their best.”

Calvert Constructs His Commando Unit

When the enemy came close to Mamyo, Calvert, thirsting for action, decided the time for training was over; what mattered now was killing as many Japanese as possible. And so he chose a solution typically Calvertian: relying on a bottle of whisky for inspiration, singing happily to himself, he burned heaps of non-essential files and set about organizing his own unit.

Calvert took with him the small staff of the school, including a handful of Australians assigned there for training. Some members of Calvert’s makeshift unit had substantial disciplinary records. His junior leaders included a number of the tough officers who taught at the school, including several of the quixotic eccentrics in which the British Army has always been rich. They included a Black Watch demolition expert, a Rhodesian who was said to have been a hangman in civilian life, and a captain who loved to eat cigarettes.

He found a couple of other allies, a Royal Marine major who commanded a few men and a launch, and the captain of a civilian river paddleboat, an elderly Royal Navy veteran with only one kidney. With this motley crew Calvert sailed up and down the Irrawaddy River, killing whatever enemy he could find and blowing up anything the Japanese might find useful. He first struck at a place called Henzada, and in a wild gun battle killed more than a hundred Japanese for the loss of only four of his own men.

Calvert went on to recruit still more men for his private commando unit—walking wounded, underemployed rear-area types, military policemen, mess attendants, and various minor offenders from the military jails. As Peter Fleming later wrote, Calvert’s lot was a makeshift unit of “odds and sods, including several lunatics and deserters.” Calvert did not lack for brash young British officers to lead this peculiar collection, youngsters eager to fight and tired of whatever they were doing.

A Tight, Tough Unit

Oddly enough, many of Calvert’s odds and sods turned out to be surprisingly good material. One was a private from the Yorkshire Light Infantry who had evaded the Japanese by swimming a river, himself wounded and pushing a raft with five nonswimmers clinging to it. Once across, he found a bottle of beer, opened it with his teeth, and walked 25 miles barefoot to a friendly town. He was Calvert’s kind of soldier.

Calvert continued to haunt the Japanese, accompanied still by the fierce Royal Marine major, but without his paddleboat, whose captain had at last been forbidden to risk his venerable craft in unlikely excursions. Calvert, adored by his men, took them perpetually in harm’s way. One raid, led by the Marine major, pitted a small detachment of Calvert’s men against four times their number of Japanese who surrounded them at night in a village called Padaung.

In a wild hand-to-hand melee in the darkness, Calvert’s men beat their enemy badly. One NCO shot three Japanese and broke the heads of two more with his rifle butt. Another sergeant split an enemy skull with the rim of his helmet, disabled another with a knee to the groin, and finished by killing a Japanese officer with his own sword.

Even when the time came for Calvert’s collection of ferocious brigands to join the dreadful retreat from Burma, his ruffians walked out as a unit, dirty, bearded, and bedraggled, but still a unit of soldiers ready to fight. Calvert led them out, dressed, for some reason now unknown, as a Burmese woman. “Those who knew him,” one writer commented, “saw nothing odd in this whatsoever.”

Wingate’s Chindits

And so, when Orde Wingate formed his Chindits, Calvert had found his element. The Chindits were regular British units trained to penetrate deep behind Japanese lines, disrupt communications, interdict supply, and draw off Japanese combat formations from the main fighting front. It was Wingate’s belief—a belief Calvert shared—that such operations were best performed not by special, elite troops like the Commandos, but by regular infantry battalions, men who trained together, shared a unit heritage, and knew one another well. Events would prove him right. His men, named for the Cinthe, the fabulous beast that guarded Burmese temples, would cause the Japanese no end of misery over the next two years.

Wingate’s tactics called for the establishment of a block or strongpoint across Japanese communications—he called such positions “strongholds.” From there, the garrison could strike in several directions at Japanese supplies and reinforcements. At least one unit from the blocking force—the “floater”—was to operate permanently outside the stronghold, so that some strength was always available to strike at the rear of Japanese besiegers. The stronghold would be established far enough from the enemy’s front that he could not easily strike at it with troops from his offensive spearhead. The Japanese would have to employ support personnel to attack Chindit penetrations, pull fighting units away from their main effort, or both.

The Vital Role of Air Supply

Wingate and Calvert were right about air resupply, too. Wingate’s Chindits would have the invaluable support of transport aircraft, fighters, liaison planes, and bombers of the Royal Air Force and the U.S. Army Air Forces. The strafing of American P-51 Mustang fighters would be critical to the success of the deep-penetration brigades. But even more important were the faithful C-47 and C-46 transports of the RAF and USAAF, flying deep into the worst terrain on earth to parachute critical supplies and ammunition to isolated Chindit columns.

Dependable resupply from the air, which the Japanese did not have, not only provided flying artillery and flew many badly wounded soldiers out to life, but insured that each battalion could use all its firepower. “The Vickers machine gun,” said Calvert, “was one of our most important weapons. I’d literally tell the troops not to use less than a whole belt at a time. There again, they’d been trained to fire in short bursts, Western Front in the First World War. With air supply, we had any amount of ammunition. The Japanese were appalled at the amount of ammunition we used.”

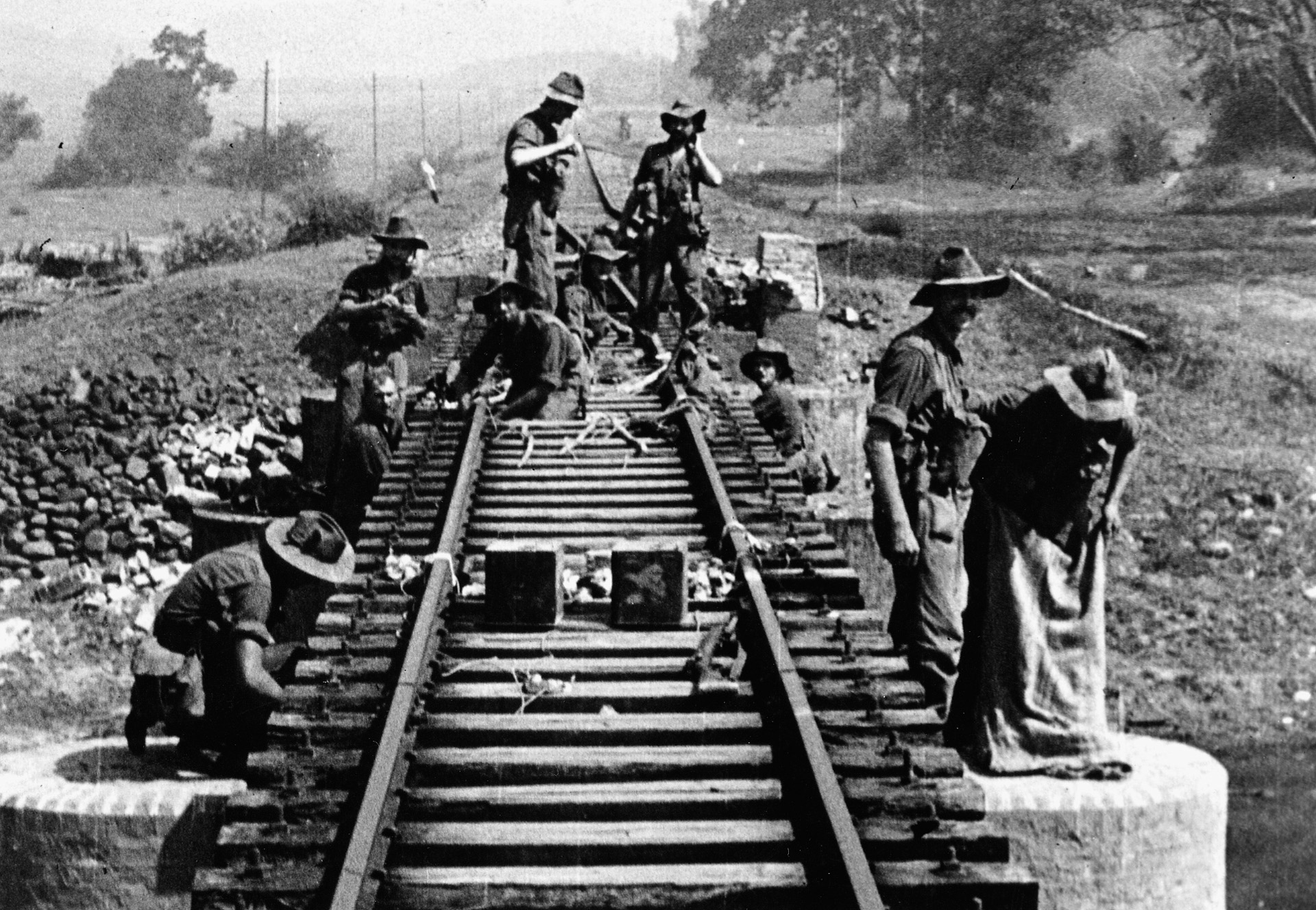

Wingate split his brigades—each of about 3,500 men—into multiple units he called “columns,” on the correct hypothesis that smaller units could move and operate more easily in the bush. His first effort, as much an experiment as an full-scale mission, sent the 77 Brigade into the rear of the Japanese 33rd Army to disrupt communications and test his new theories. Calvert, leading one of the brigade’s 400-man columns, blew two critical railway bridges without losing a man, then went on to ambush Japanese personnel and supply columns. His backtrail was littered with Japanese dead.

British Prove They Can Handle the Fierce Jungle Fighting

The other columns did not fare as well in this maiden voyage but, in spite of their considerable losses, a point was clearly made. The Japanese were not the invincible masters of the jungle. Regular British units could fight them on their own ground and do so on at least even terms. The example was not lost on the rest of the army. “And really,” Calvert told this author, “in some ways the greatest effect we had was the ordinary officer and soldier saying, ‘If those bastards can do it, we can do it.’”

Much of the Burma fighting was at very close range, some of it with bayonet, knife, entrenching tool, Gurkha kukri, or whatever other weapon was nearest to hand. During one close-quarters fight to clear a vital pass, a Gurkha shot a sword-waving Japanese officer in the belly with his PIAT anti-tank weapon. As Calvert tersely put it: “The officer and the counterattack rapidly disintegrated.”

And in March 1944, a wild charge up a vital piece of high ground called Pagoda Hill, an attack led by Brigadier Calvert in person, turned into a ferocious hand-to-hand fight for the crest. There, a South Staffords lieutenant had his arm cut off by a Japanese officer’s sword. Ignoring the blood and pain, the young subaltern shot the Japanese then picked up the sword and hewed at every enemy within reach until he collapsed. The high ground captured, Calvert ran to the young officer and knelt beside him.

“Have we won, sir?” the lieutenant asked his commander. “Was it all right? Did we do our stuff? Don’t worry about me.” And then the youngster simply died, another good man gone in the spiteful, no-quarter jungle war.

Such heroism and tragedy were commonplace. In Lt. Col. John Masters’ Chindit brigade, Number 111, Captain Jim Blaker would win the Victoria Cross leading a wild Gurkha charge that drove the Japanese from an impregnable position, against all hope. But Blaker paid for the victory, as an inordinate number of British officers did, down and dying with seven machine-gun bullets in the stomach. With his last strength he urged his tough little soldiers on: “Come on, C Company, come on. I’m going to die. Take the position!”

And his men did, with bayonet and kukri, scrambling past their commander’s body, roaring their war cry, “Ayo Gurkhali!” When it was over, nobody had the strength to bury poor Blaker and the Gurkhas who had fallen with him. Only three months later would a detail find and bury them, bamboo growing six feet tall through their remains.

The Chindits Work to Stop Operation Ha-Go

In March 1944, the Japanese began Operation Ha-Go in the southern part of Burma, prelude to the much larger effort called U-Go, which was nothing less than a maximum effort across the Chindwin and into the Naga Hills of eastern India. The goal was to penetrate west into Manipur State, into India itself. Ha-Go was a failure, however, and U-Go, the major offensive, was destined to be an unmitigated disaster for the Japanese. They were first beaten back at the tiny hill-station of Kohima, where a small garrison threw back repeated assaults by much larger Japanese units. The final blow came in the fighting around Imphal, where the British battered and repelled the Japanese 15th Army then pursued its remains back across the Chindwin into Burma.

In the same month, Wingate launched a major effort in support of the British defense against Ha-Go. Calvert by now commanded the 77 Brigade, which flew in gliders to a landing zone (LZ) called Broadway, some 50 miles northeast of the town of Indaw. This time the Japanese assigned the equivalent of an entire division to counter the ravages of the Chindit columns, including Calvert’s own. It did not work, and the Japanese lost heavily.

The men of 77 Brigade set up a block called White City along the vital railroad south of the town of Mawlu and held it for two months against frantic Japanese efforts to overwhelm it. Before the ferocious fighting there was over, more than a thousand putrefying Japanese corpses sprawled in the jungle or hung in the Chindit wire around White City. March also brought tragedy when Wingate was killed when his aircraft crashed among the wild hills of eastern India.

The 77 Brigade’s defeat of the Japanese at the White City block had been a great success, but their finest hour was still to come. In the first week of May 1944, Calvert started his brigade north through the monsoon to attack the town of Mogaung, supply conduit for the Japanese fighting Stilwell’s Chinese divisions, pushing, however slowly, south toward the critical town of Myitkyina. If Calvert’s men could take Mogaung from its large garrison and hold it, the Japanese lifeline northward would be cut. Myitkyina would fall.

Along the way, Calvert tried to go to the aid of a Chindit outfit—Jack Masters’ 111th Brigade—hard pressed in the stronghold called Blackpool. But the Namying River lay between Calvert’s men and Blackpool, and the river was so swollen with monsoon rains that it was entirely impassable. The soldiers of the 77th Brigade could not help their struggling comrades and continued on to the north. Calvert’s orders, which came from Stilwell’s headquarters, were to carry Mogaung, even though his tired, understrength brigade lacked any fire support heavier than a 3-inch mortar, and the dug-in enemy possessed mortars as large as six-inches. Calvert was promised support from Chinese units, but that support was never to materialize.

The Battle for Mogaung

And so Calvert and the 77 Brigade would carry the whole load at Mogaung. By now, the brigade was shot with malaria, typhus, and a dozen other vile diseases. Many men had foot rot so bad that they could not run; their best pace was a painful shuffle. The men who would do the hardest part of the work—the British and Gurkha infantry—were very thin on the ground. There were only a couple of thousand of them left standing when they began the last push to Mogaung, and many of these were walking hospital cases, marching on willpower alone.

Calvert’s units included the 3/6th Gurkhas and the first battalions of the King’s Regiment, the South Staffordshire Regiment, and the Lancashire Fusiliers. Along with them were detachments of the Burma Rifles, tribesmen led by British officers, and an assortment of engineers, RAF liaison personnel, and medical personnel. Among Calvert’s soldiers was a platoon of the Irish Army. Their leader, “a marvelous chap,” Calvert called him, “was a sergeant in the Irish Free State Army, and when England’s future looked low at the time of Dunkirk, he took his whole platoon over on the Angelsey ferry and joined the British Army … they all fought extraordinarily well”

The head-on attack on Mogaung, against a dug-in enemy in prepared positions, was not the sort of combat for which the lightly armed Chindits were designed. Nevertheless, orders were orders, and 77 Brigade went in to the attack. The battle for Mogaung was vicious, close range, a fight to the finish. Although USAAF Mustangs bombed and strafed in support of the ground assault, often six sorties per plane per day, in the end the work had to be done with rifles and bayonets, kukris and grenades, machine guns and flamethrowers.

As usual, Calvert’s young officers were out in front of their men, setting the example, taking hideous casualties. Captain Mike Allmand, for instance, far in front of his Gurkhas, exterminated a Japanese machine-gun nest himself and directed his men’s flamethrowers to incinerate other Japanese defenders … until he fell, hit twice.

Using grenades, flamethrowers, and PIATs, the spring-loaded antitank grenade projector, Allmand’s Gurkhas cleared one particularly tough position, a house from which intense Japanese fire enfiladed the British advance. But Captain Allmand’s luck had run out. He was down and dying by the time the position fell, shot down as he slogged through thick mud to attack, his feet too ravaged by rot for him to run. He would receive the Victoria Cross.

Another Victoria Cross went to Gurkha rifleman Tulbahadur Pun, something of a one-man army, who charged alone across 30 yards of open ground. Firing his Bren gun from the hip, he captured two Japanese machine guns, killed or routed their crews, then covered the advance of the rest of his platoon.

No Way to Go But Straight Ahead

For Allmand and Pun and their comrades, the going was bloody and tough. There were at least 3,500 dug-in Japanese in Mogaung, more men than Calvert had. And there was no way to go but straight ahead for Calvert’s sick, exhausted men.

One Fusiliers officer was killed because he advanced standing up, a sitting duck for the Japanese; he was simply too exhausted to crawl. There was little rest for anybody, and then only for a few hours. “Heaven was a letter from home, dry feet and a tin of British steak and kidney pie,” one veteran said. Calvert’s men fought on through the endless rain of the monsoon, slogging and crawling through mud and corpses and the vile, pervading stench of burned human flesh.

The British were cheered a little by the knowledge that their enemy was weakening too. The Fusiliers, cooking rations in positions taken from the Japanese the same day, watched in amazement as a weary Japanese patrol walked into the British position and began to shed their weapons and equipment. The Fusiliers finished off the Japanese quickly, then returned to the all-important business of food.

The British patrolled incessantly at night, tossing grenades into Japanese bunkers, penetrating all the way into Mogaung town to ambush stray Japanese soldiers and booby trap equipment and food. One favorite British occupation was to cut Japanese telephone lines by night, thoughtfully booby trapping the cut ends with grenades.

The trees were full of Japanese snipers; the patches of scrub concealed hidden riflemen and machine-gunners. The British losses mounted until Calvert’s battalions were down to company strength. The casualties in officers were particularly high. In the South Staffords, only one lieutenant remained of those who had marched to Mogaung. Over time, that battalion had 40 officers killed or wounded. Only two platoon leaders remained on their feet. One had been wounded four times, the other three. At this point, a deputation of platoon sergeants came to Calvert, volunteering to lead platoons in hopes of saving “so many keen, inexperienced young officers.”

Major Archie Wavell, son of the Viceroy of India, walked calmly to the rear, holding his almost severed hand, still in command, still giving orders. After treatment, Wavell refused to be evacuated until every soldier more seriously hurt than he had been flown out. Evacuation of the wounded was more difficult now, as the weather grew worse and worse. The brigade surgical team labored desperately to save lives in gooey mud and drenching rain, only to have critically wounded patients lie for days awaiting evacuation. Calvert was entirely dependent on aircraft controlled by Stilwell’s headquarters.

Many days Calvert was told that no aircraft were available. But even during the worst weather, a single American NCO pilot flew his tiny L5 into Mogaung, often against orders, one day flying 14 70-mile round-trip sorties to bring out critically wounded Chindits. This gallant sergeant flew in, kept his engine running, got his pitiful load, then took off again into the monsoon. And did it again and again. Wrote Calvert, simply, in later years, “I salute him.”

Bravery and Discipline Despite Fatigue

Calvert’s men were moving like automatons, shot with a dozen diseases, soldiering on with unhealed wounds, but determined to throw the Japanese out of vital Mogaung. When Calvert urged one South Staffords soldier to keep up with his section, the man apologetically showed him a freshly reopened wound covered by a bloody bandage. “The bullet’s still in, sir, but I wanted to join in this last attack.” And Calvert’s indispensable brigade major, Francis Stuart, served on even though, as Calvert said, “He was shot with tuberculosis. He was dying, and I think he knew it, but he stayed on because he was needed.”

Lieutenant Wilcox of the same unit—already wounded twice at White City—was shot through the neck just below the chin. He was quickly back with his unit, fighting on with a roll of gauze stuffed clear through the wound. During breaks in the fighting, he would pull the gauze through the wound to clean it, like a pull-through in a rifle barrel. Later Wilcox was shot in the head, had the scalp sewn up, and returned to his platoon to serve until Calvert personally ordered him evacuated. Wilcox would win both the Distinguished Service Order and the American Silver Star. To Calvert he was “a worthy representative of all the other subalterns who did not last so long.”

To the end, British discipline remained tight, unit spirit and morale amazingly high. After the war, a senior Japanese commander in Burma commented, “The British forces maintained their traditionally high standard of discipline throughout a most difficult campaign. The high standard of morale and discipline of the Colonial forces surprised the Japanese troops.”

Foul tropical diseases and Japanese bullets were not the only dangers in the quagmire of Mogaung. Concerned by the great number of soldiers hobbling from trenchfoot, Calvert asked for gum boots to protect the feet of soldiers perpetually living and fighting in deep mud. A distant headquarters responded: “It is the medical opinion that … wearing gumboots injures the feet … the best insurance against trench feet is to keep the feet dry.” Even after 50 years, Calvert’s comment on that advice was unprintable.

Mogaung Finally Falls

But bunker by bunker, the 77 Brigade closed on Mogaung in spite of mud and torrential rain, vicious Japanese resistance, and foolish messages from higher headquarters. Calvert held one officers’ call in a bomb crater, pervaded by the sick-sweet stench of Japanese killed and wounded by flamethrowers; some of them were still screaming as Calvert gave his orders. The final push was coming. The brigade was down to a handful, some 550 effectives out of the 2,355 who had come to Mogaung.

On June 14, Calvert ordered a British captain commanding a Burma Rifles patrol to go and find some of Stilwell’s inert Chinese and not to return without bringing at least a regiment. Four days later the captain simply reported to Calvert that he had indeed found and brought a Chinese regiment, now waiting just across the Mogaung River. Now there would be some help in keeping the town absolutely isolated, and some assistance from the Chinese 75mm artillery. Calvert was moved to comment on the officer who had produced this miracle: “We had all come to take these wonderful Burma Rifles officers for granted. You would say, ‘Bring me six elephants,’ or ‘a river,’ … or a ‘Chinese regiment,’ … and they would look at you from behind their moustaches, salute, disappear followed by a worshipful company of Kachins, Chins, or Karens, and then appear with whatever you wanted.”

The final major defense line at Mogaung was the railway embankment, running roughly north to south, carrying the vital Myitkyina railway. The British went in before dawn, South Staffords leading, clearing the Japanese strongpoints along the embankment with grenades and flamethrowers. Then the Fusiliers and a Gurkha company passed through them to hold the gains. The last Japanese line was broken.

And then, on June 25, suddenly, anticlimactically, it was over. The remnants of the Japanese defenders were gone. Calvert’s Gurkhas were in Mogaung unopposed, soon followed by a swarm of Chinese, looting and destroying. The town had been, as Calvert described it, “a pleasant place with wide tree-lined streets,” substantial buildings, and a thriving commerce. Now it was a wreck, ravaged by bombs and artillery. Its only occupants now were abandoned dogs and cats.

The few surviving Japanese had fled on improvised rafts, gone on downriver to join what remained of the imperial forces. Only a couple of dozen Japanese officers and men remained in the ruins, hiding on the river bank, probably men who could not swim. A Gurkha patrol dealt with them, and silence fell at last over the ruins of Mogaung.

Calvert Takes on Vinegar Joe

It had taken 16 days of concentrated fighting and a hideous casualty list. The men of the 77 Brigade and their commander had every reason to be deeply proud. Only one irritant remained. “It was,” as one historian pungently commented, “a victory marred by those necessary lice on the military body, the public relations staff.” Incredibly, the announcement from Stilwell’s headquarters claimed that the Chinese had taken Mogaung.

Calvert was furious. There were too many graves behind the 77 Brigade, too many good men gone back to India without arms or legs, too many soldiers whose health had been broken forever. But Calvert’s revenge was, especially for him, remarkably restrained. It was certainly subtle. His signal to Stilwell’s headquarters is a military classic: “The Chinese having taken Mogaung,” it read, “77 Brigade is proceeding to take Umbrage.”

The story goes that at Stilwell’s headquarters his staff—the British called them the Stuffed Baboons—searched diligently through their maps one long night, looking for this mysterious place called “Oom-brah-gay.” It is even said that the baboons queried Calvert, asking for the map references of this tantalizing place they could not find on the map. The 77 Brigade had shot its bolt and had to be evacuated. As Calvert said many years later, “[My men] were so out on their feet that two soldiers died afterward of simple exhaustion, on the walk out. And those two were among the handful who were still ‘fit for duty.’”

Calvert would meet the notoriously anti-British Stilwell, who chided the Englishman, “Calvert, those were strong signals you sent,” to which Calvert replied, “You should have seen those my Brigade Major would not let me send.” Something in the response appealed to Vinegar Joe, who awarded Calvert the Silver Star and gave him four more to distribute among his men.

For Calvert and the Chindits, the Burma war was over. With the Japanese in full retreat, the Chindit units were disbanded, including what remained of the 77 Brigade. Calvert would finish the war in Europe, heavily decorated, commanding an SAS brigade. But nothing would ever quite equal the sacrifice and pride of the Burma days, the days of White City, Pagoda Hill, and Mogaung.

Author Robert Barr Smith is a retired U.S. Army colonel and serves as associate dean for academic affairs at the University of Oklahoma Law Center in Norman.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments