By Donald J. Roberts II

Within a week of the Los Baños raid, paratroopers from Burgess’s 1st Battalion moved back into the Los Baños area to occupy the region. They made a horrible discovery—the Japanese 8th Division had committed brutal atrocities against Filipino civilians in the area.

The unit primarily responsible for the attacks on the civilians was the Saito Battalion, under the command of Captain Ginsaku Saito. Following the successful American/Filipino raid, Saito ordered two companies from his battalion, plus a group of ex-guards from the Los Baños prison camp, back to the camp “to kill all guerrillas, men, women, and children in Los Baños.”

For three days, Saito’s men shot, bayoneted, and set fire to as many civilians as possible. By the time Burgess’s men arrived in Los Baños, over 1,500 people had been killed.

“Sadistic Tendencies” around Lagune de Bay

The investigations that followed the murders generally agreed that the reason for the attack was a Japanese reprisal against the civilians in the area for supporting the American raid. Some people, however, believed the Japanese would have committed the brutal acts against the civilians whether the raid was conducted or not. There had been plenty of “sadistic tendencies” around Laguna de Bay in settlements such as Calamba and Canlubang before the rescue mission. Former inmate Ben Edwards said, “I do not believe the atrocities in and around the college were the direct result of the liberation. I have always been of the opinion that the taste of defeat [in the Philippines] drove the Japs into a frenzy that set off sprees of killing.”

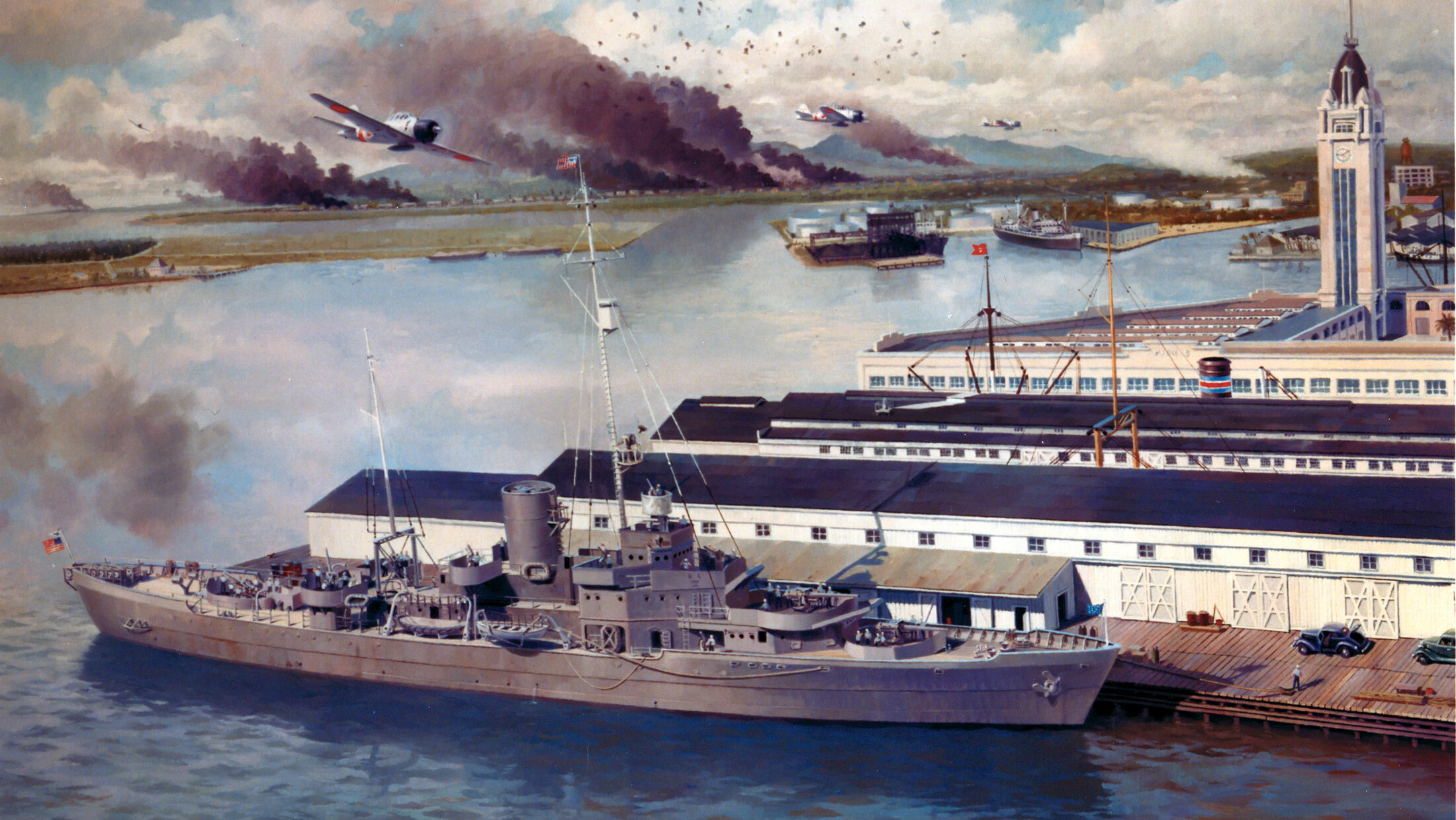

During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, it became standard procedure for the occupation troops to conduct reprisal raids on civilians whom the Japanese suspected of aiding guerrillas. In 1943 when the Japanese began to consolidate their positions in the Philippines, they began a program designed to destroy the countless guerrilla bands throughout the islands. As the Japanese increased the number of patrols designed to capture guerrillas and their sympathizers, they began to execute each member they captured. As the raids grew larger and the “sweeps” intensified, the Japanese only grew angrier over their failures to suppress guerrilla activity. In addition, the Japanese suffered from frequent ambush attacks from guerrilla units as the tired and worn-out patrols returned to base.

Increasing the Level of Harsh Treatment

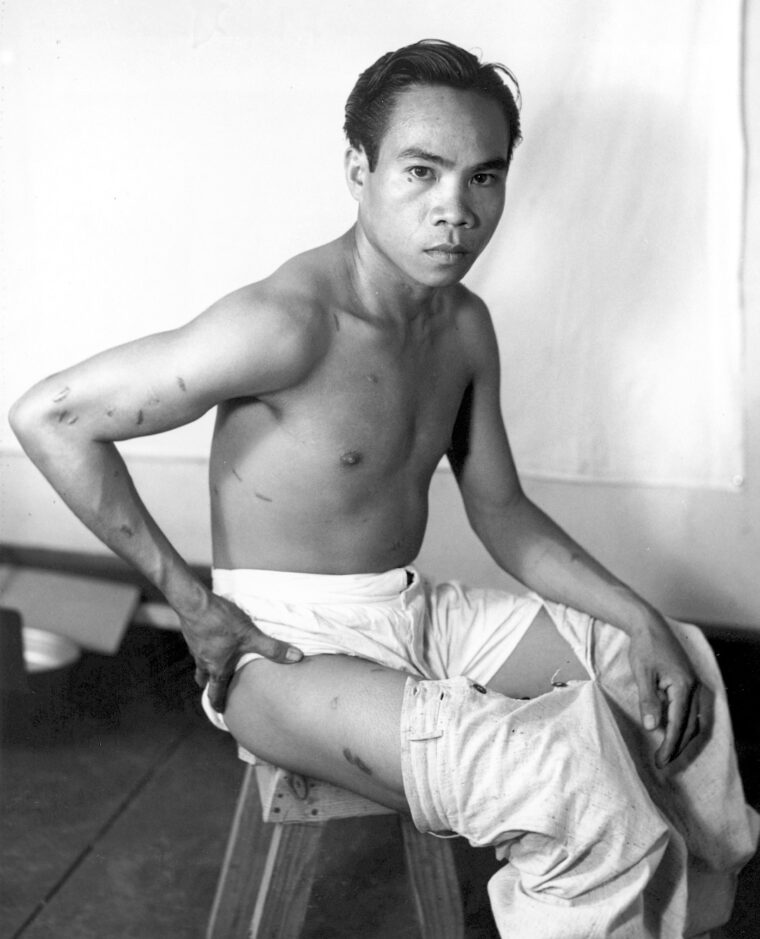

Frustrated, the Japanese increased the level of harsh treatment to the civilian population. Guerrilla or sympathizer suspects were often subjected to the salt-water torture: A person was tied throat to hands and feet so that struggling led to strangulation; the mouth was forced open and the nose pinched; seawater was poured into the mouth so that the victim had to swallow to breathe; if he talked, the torture stopped; if not the Japanese continued the torture until death.

Water torture, as well as other cruel treatments, caused many Filipinos to flee into the jungle. The Japanese would often pursue and many times kill an entire family when they caught them. They would also burn entire villages to prevent civilians from supporting guerrilla operations. In turn, bands of guerrillas effectively harassed Japanese military operations. Initially, these attacks against the Japanese were fragmented with little direction and focus. But slowly men like Lt. Col. Ruperto Kangleton, a Filipino Regular Army officer who had escaped capture, began to organize guerrilla operations throughout the Philippines.

Organizing a Resistance

Soon others, including American officers and men who had eluded capture, began organizing guerrilla and resistance movements all over the islands. In 1943, after contact was made with Australia, supplies, arms, and selected liaison personnel were transported to the islands by submarine in significant quantities to make a decided impact on guerrilla operations. Until the American liberation of the Philippines, these guerrilla groups were able to disrupt Japanese operations, ambush patrols, cut communication lines, and in general, make life miserable for Japanese occupation troops.

As guerrilla activity increased so did the atrocities against those suspected of aiding guerrillas. The main reason for such a tremendous guerrilla network was the harsh treatment of Filipino civilians by the Japanese. By the time of the Los Baños raid, Japanese brutality toward Filipinos was commonplace.

But Japanese brutality was evident from the first day of occupation. It is “doubtful that those who were engaged in any sort of guerrilla activity were pro-American by conviction,” according to Robert B. Asprey (War in the Shadows: The Guerrilla in History, Vol. I, Doubleday & Company, 1975). For the most part, with a few exceptions, “there was no real understanding of the basic issues involved in the war between the United States and Japan.” At the same time, it was believed that the Filipinos had not “developed any feeling of real attachment to the Americans, not having closely mixed or associated with them, socially or otherwise.” The real reason to join the Filipino guerrilla movement: “the sad and often tragic experiences which they or their relatives, friends, and countrymen had undergone at the hands of the Japanese.”

Through the entire experience of Japanese occupation of the Philippines, the Japanese were never able to understand the aversion exhibited by the Filipino people against them. The basic cause for the relentless guerrilla activity was the Japanese lack of “respect for common people.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments