By John Walker

Rear Admiral Keiji Shibasaki, commander of the elite Japanese garrison entrenched on tiny Betio Island in the central Pacific Ocean, boasted in mid-1943 that his heavily fortified island redoubt could hold out “against a million Americans for a thousand years.” The United States Navy, in contrast, believed that its planned amphibious assault upon Betio, one of a collection of small islands surrounded by coral reefs that made up Tarawa Atoll, stood an excellent chance of success. New techniques in naval bombardment, Navy tacticians believed, would practically annihilate any defensive forces on the island. Indeed, the admirals commanding the warships supporting the landing forces assured senior U.S. Marine Corps officers that Betio would be pounded into coral dust before the landings even began.

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet, envisioned a limited, two-division offensive starting with an invasion of the Japanese-held Gilbert Islands to develop airfields and facilities to support future American operations against the strategic Marshall Islands. Nimitz established the Central Pacific Force under the command of Rear Admiral Raymond Spruance. It consisted of three major subordinate components: the Fifth Amphibious Force commanded by Vice Admiral Richmond K. Turner, with a ground force, the V Amphibious Corps, under Marine Maj. Gen. Holland M. “Howlin’ Mad” Smith; the carrier force; and the air force.

The attack, code-named Operation Galvanic, would be a joint Marine-Army operation and initially involved Tarawa and Apamama in the Gilbert Islands chain, and the island of Nauru, which lay almost 400 miles to the west. The first two would be the 2nd Marine Division’s objectives; Nauru would be the Army’s first action in the Central Pacific campaign. Spruance, however, changed the Army’s objective from Nauru, a relatively well-defended objective that would require more troops than there were available transports, to the Japanese seaplane base at Makin Atoll, 140 miles northeast of Tarawa Atoll. The change in objective left the Army little time to prepare for its combat debut. The assault force at Makin would be limited to one regimental combat team, built around the 165th Infantry Regiment and the 3rd Battalion, 105th Infantry Regiment, and would be supported by field artillery and engineer and tank battalions.

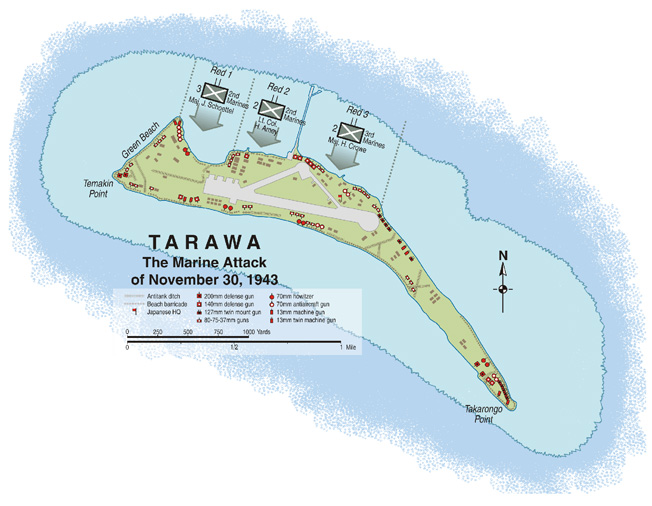

Betio Island

The main objective of the 2nd Marine Division attack upon Tarawa would be Betio Island. The attack upon Betio would be the first American amphibious assault against a heavily defended beachhead and, as such, would be a crucial test of Marine Corps amphibious doctrine. Set to begin on November 20, 1943, Operation Galvanic proposed to conquer within five days the atolls of Makin and Tarawa. Flat and sandy over sharp coral bases, these islets, unlike the densely vegetated, mountainous terrain of Guadalcanal and New Guinea, provided no surface cover for defenders or invaders. The Japanese had thus tunneled deeply into the coral to provide themselves with excellent protection against bombs, shells, and small-arms fire. The intelligence about Makin estimated a fairly small garrison, and American strategists believed a massive strike from the air and sea would soften up the defenders sufficiently for a quick victory.

The Americans anticipated a much harder fight at Betio, a 291-acre fortress with a newly built airstrip, girdled by a three-to-five-foot-high seawall and stuffed with concrete and coral emplacements housing numerous antiship guns and troops. The enemy on Betio could bring to bear 14 coastal defense guns, including four Vickers 8-inch naval rifles scattered around the island in concrete bunkers, 14 light tanks, 40 artillery pieces, and infestations of heavy and light machine guns. The seaward approaches bristled with concrete tetrahedrons festooned with mines and barbed wire; trenches connected all sectors of the island, allowing the defenders to move under cover when necessary.

A Deadly Coral Ridge

As troubling as the man-made defenses was the coral reef that entirely ringed Betio. The hard, jagged, natural obstacle could hang up landing craft, rip open bottoms, and force attackers to wade through deep water to reach the shore. Experts who had guided ships in the Gilberts predicted five feet of water over the reef at high tide, barely adequate for the Higgins LCVP (landing craft, vehicles and personnel) boats that ordinarily drew four feet. The Pacific Fleet had also begun deploying LVTs (Landing Vehicle, Tracked), amphibious tractors nicknamed “Alligators” that could crawl across a reef if necessary, but only a limited number—50 new LVT-2s and 75 old LVT-1s—were available for Tarawa.

On an ominous note, Major Frank Holland, a New Zealand reserve officer with 15 years of experience sailing the waters off Tarawa, warned that the tides there frequently fell below the norm in November; he begged Marine officers to delay the landings for five weeks until there was no chance of the low “dodging” tides. Although Nimitz and the operations staff fretted over the problem, they were pressured not to postpone operations in order to await more favorable tidal conditions. Allied momentum in the Pacific was quickening and, it was thought, any delay might allow the enemy time to regroup and reinforce its positions. Indeed, a long-range, multiservice amphibious operation the size of Galvanic was almost too complex to alter. Plans and schedules had been worked out months in advance, with cargoes waiting in a dozen ports for the assault ships. Short of cancellation, there was no way to alter the operation.

The Plan of Attack

Questions about tactics also stirred debate, especially in the matter of air and naval bombardment. Maj. Gen. Julian Smith, whose Marines would ride the Alligators and LCVPs to the beaches, wanted a lengthy artillery bombardment from the big guns offshore and from the air. Navy brass worried that this would alert the enemy and bring the ships and planes of the Japanese Combined Fleet down upon the U.S. Fleet. It was a misplaced worry. Heavy aircraft losses and the disabling of four heavy cruisers in the Solomon Islands meant that the Japanese plan to react forcefully to any American thrust in the Gilberts was scrapped, and the garrisons at Tarawa and Makin were left to their fates. The 5,000 defenders on Betio, with no chance of reinforcement or air support and forbidden by Imperial decree to surrender, had no alternative but to fight to the death. They would take many Americans with them.

Betio’s reef lay 500 to 800 yards from the beach and averaged 50 yards in width. There was only one boat passage into the lagoon, a narrow cut opposite the center of the island’s northernmost beach, about 500 yards from shore. A narrow pier, 500 yards in length, connected the passage with the island. If the tide was too low, almost the entire American assault force would be channeled toward the pier, or else the troops would have to wade through the surf for several hundred yards through withering enemy gunfire to reach the northern beaches.

Because of the possibility of low tidal conditions and the barrier reef, the three initial assault waves—six augmented companies of about 1,500 Marines—would be transported to the beach aboard nearly all the 75 old and 50 new landing boats. If the water was high enough at the reef, subsequent troops, heavy weapons, and supplies would be ferried in aboard light- and medium-weight LCVPs, or Higgins boats. If the water were too low for the boats, tractors would be used to shuttle additional troops ashore. The landing zones were three primary beaches, each about 600 yards in length, on Betio’s north shore. The first three battalions to hit the beaches would be the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 2nd Marine Regiment, and the 2nd Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment. Beaches Red 1 and Red 2 lay to the west of the pier that extended out into the lagoon, and Red 3 lay to the east. Army Air Corps bombers that struck Betio reported weak antiaircraft opposition, raising hopes that most of the Japanese defenders had been evacuated or were dead.

The Assault Begins

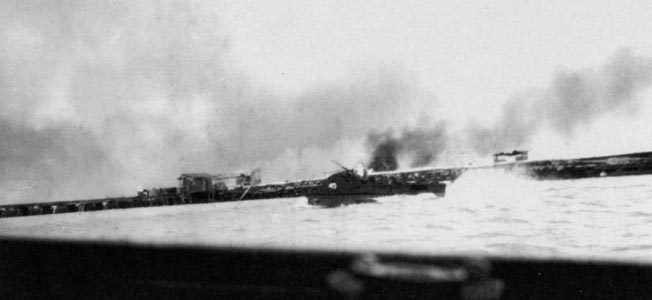

At 4 am on November 20, the first waves of amphibious tractors loaded with Marines chugged through the channel toward the line of departure, the rendezvous point from which the first three waves would begin making their way toward the beach. Overhead, shells from Japanese shore batteries testified to life and fight on the island. The battleship Maryland answered with full-throated roars from its 16-inch cannons. Two other dreadnoughts, four cruisers, and 20 destroyers cascaded 3,000 tons of ordnance upon the island, pausing only long enough to allow carrier planes to swoop in and deliver their own loads of explosives. It was the heaviest bombardment of any invasion beach to date.

Correspondent Robert Sherrod, watching from the deck of the transport Zeilin, wrote: “The sky at times was brighter than noontime on the equator. The arching, glowing cinders that were the high-explosive shells sailed through the air as though buckshot were being fired out of many shotguns from all sides of the island. The whole island of Betio seemed to erupt with bright fires that were burning everywhere. They blazed even through the thick wall of smoke that curtained the island. Surely, I thought, if there were any Japs left on the island (which I doubted strongly), they would all be dead by now.” Sherrod apparently did not hear the warning issued by Colonel Merritt Edson, chief of staff of the 2nd Marine Division, who predicted, “We cannot count on heavy naval and air bombardment to kill all the Japs on Tarawa, or even a large proportion of them.”

The gigantic blasts flung smoke, sand, coral, chunks of wood, concrete, and steel into the air. Concussive effects momentarily stunned the well-shielded defenders, many of whom staggered from their bunkers bleeding from their noses, eyes, and ears. Unfortunately, the Marines were unable to exploit the brief period when the enemy was dazed—the first waves required longer than expected to make it to shore. Smoke and haze from the pre-invasion barrages prevented naval observers (as they had warned) from using their heavy guns to the best advantage; the carrier-based aircraft ended their strafing runs too soon, as well.

Marines Hit the Beach

Only the first wave of assault teams neared the beach before the Japanese recovered and commenced to fight. The timetable called for the first wave to hit the assigned beaches—Red 1, 2, and 3 from west to east—at 8:30 am, but miscalculations of the distances and the rate of speed of the amphibious tractors through the choppy waters, delayed the arrival until 9:13. The offshore bombardment was revived for a few minutes, but the defenders still had almost 20 minutes to recover their senses and man their weapons. Some groups of landing craft met relatively little opposition, but at Beach Red 1 devastating fire from an area called “the Bird’s Beak” savaged the Marines of the 3rd Battalion.

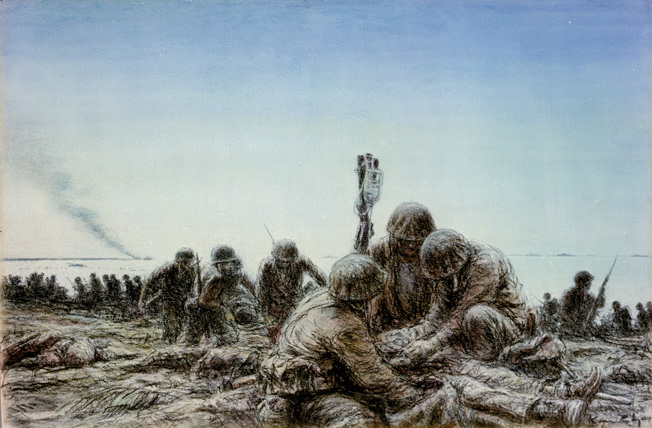

The first three waves, shuttled to the beach in 87 Alligators, were unable to move forward off the narrow beach after they made their way ashore; the Japanese defenses were intact and manned by determined foes. Pinned down, the Marines lay at the base of the coconut-log and coral-block seawall, unable to advance or retreat. Within minutes of the start of the assault, the Navy’s battle plan had gone awry, and numerous Marine troop leaders had been killed. From pillboxes, machine-gun nests, and bunkers that were camouflaged and invisible to the Marines, the Japanese sent a murderous storm of bullets and shrapnel spewing out across the airstrip toward the reef, where the carcasses of 20 disabled amtracs and a pair of LCVPs loaded with Marine dead and wounded had piled up.

Destroying the Japanese Bunkers

The tide stubbornly refused to rise sufficiently to allow LCVPs loaded with reinforcements, tanks, and artillery to navigate the coral ridge. The heavily laden Marine riflemen aboard the stranded LCVPs had no alternative but to pile out of their boats and begin wading toward shore, 500 long yards away, through a hail of murderously accurate gunfire. Marine Private Clayton Jay, from Lamesa, Texas, was one of the waders. “Our tractor was about 25 yards or so from the beach when the corporal sitting next to me was struck by enemy fire,” Jay recalled. “He slumped over on me with half his head gone. The rest of us dove out the back of the tractor, running around the side of it to the seawall. I had a chance to look around. Bodies of Marines were floating in the ocean and on the beach. Behind me I could see Marines wading in rifles, above their heads, being cut down by the Japs’ small arms fire. It was awful. Blood from the dead actually turned the water a bright crimson red.”

Once ashore, the Marines attacked pillboxes with their small arms, a few flamethrowers, grenades, and blocks of TNT fashioned into pole charges. The 2nd Scout-Sniper Platoon, led by 1st Lieutenant William Hawkins, landed first, wresting the 750-foot-long pier from enemy snipers and machine-gun nests and killing 25 of the defenders. Meanwhile, the first elements of the 3rd Battalion came in on Beach Red 1. On the left of the beach, at the boundary with Beach Red 2, an enemy strongpoint dubbed “the Pocket” raked the Marines coming in on the west side of Red 1 with withering machine-gun fire. The Marines on Red 1 suffered 35 to 50 percent casualties before they even made it to shore.

The most violently opposed landing was on Beach Red 2. Some of the Marines were driven off course by machine-gun and antiboat fire and were forced to land on Red 1. The remainder, which reached Red 2, managed to carve out a beachhead only 50 yards deep. Company E had five officers killed almost immediately. Staff Sergeant William Bordelon, of San Antonio, Texas, took matters into his own hands. The combat engineer from Company C, 1st Battalion, 18th Marines, personally destroyed four enemy pillboxes, despite being wounded twice. He was heading for a fifth bunker when he was cut down by enemy machine-gun fire. For his bravery, Bordelon was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

“The Sons of Bitches Can’t Hit Me!”

Red 3 was the next beach reached by the Marines; part of the 2nd Battalion got as far inland as the airstrip before the Japanese defenders recovered from the naval bombardment. Battalion commander Major Henry Crowe led by example. After his landing craft slammed into the reef, he jumped into the water and waded several hundred yards toward shore through knee-deep waves. “Look,” he shouted to his men. “The sons of bitches can’t hit me! Why do you think they can hit you? Get moving!” With the help of covering firepower from the destroyers Ringgold and Dashiell, the Marines were able to gain a small foothold on Red 3.

Once the first three waves of Marines were in, two more waves of landing boats were set to follow, carrying additional troops, tanks, and artillery. When their LCVPs were unable to negotiate the reef, the infantry and howitzer crews had to wade ashore with weapons and equipment. These men suffered the worst casualties of D-day; the only cover from enemy machine guns and riflemen was the pier, but many were unable to reach it. Those who did were separated from their units and unable to reach their assigned beaches. At this point, the momentum of the assault bogged down, with the reef effectively barring the LCVPs, the number of amtracs being rapidly reduced, and spotty communications adding to the overall confusion. The fierce fighting taking place ashore prevented the Marines from regrouping, establishing command posts, or moving in supplies. They could not even carry out their wounded.

Nightfall

The LCVPs bearing 37mm cannons could not pass the reef and were forced to wait until nightfall to make their approach. Ten Sherman tanks, disgorged at the outcrop, climbed over the natural barrier through three or four feet of water, rattling onto the beach and adding their firepower to the beleaguered invaders. Although all but two of the tanks were knocked out by day’s end, the firepower they unleashed against enemy pillboxes helped the Marines move their beachhead forward several hundred yards before nightfall. By 12:30 pm, the Marines had successfully taken the beach as far as the first line of Japanese defenses. By 3:30, the line had moved inland in places but was still generally along the first line of enemy defenses. The arrival of tanks started the line moving again on Red 3 and the end of Red 2. By nightfall, the Marine lines were about halfway across the island, only a short distance from the main runway.

The Marines’ situation was tenuous at best; about 5,000 Marines were ashore, but 1,500 of them had been killed or wounded in the process. The Marines held a perimeter about 700 yards wide and 300 yards deep at the base of the pier and an area about 150 yards by 500 yards at the northwest tip of the island. While the Marines held their hard-won ground, the first 75mm pack artillery began to land during the night along with medical supplies, water, and ammunition. Much-needed reinforcements straggled in as well.

The Japanese, notoriously skilled at night attacks, might well have been able to eliminate the beachhead, only 300 yards wide at most places, and drive the Marines into the sea had they mounted an all-out counterattack on the first night, as prescribed in Shibasaki’s operational orders. The constant barrages from American battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and aircraft, however, along with the small-arms fire and explosives from the landing forces, destroyed the lines of communication between Shibasaki and his units. Half of his own force was dead or wounded.

Day Two

For Colonel David Shoup, commander of all ground forces coming ashore, the first day had been harrowing and painful. During the three hours after sunrise, his three initial landing teams had been strewn across three beaches, reef, and lagoon. All had fought major, unremitting actions, and there had been little the commander could do to help. Despite being raked in the leg by enemy shrapnel, Shoup had finally made it ashore at noon and established a command post 50 yards in from the pier along the blind side of a large Japanese bunker, still occupied. As the sun rose above Shoup’s shell-hole command post on the morning of D-day + 1, the issue remained very much in doubt. He radioed a number of imperative messages, calling for ammunition, water, rations, medical supplies, and evacuation of the wounded. Sherrod, on the scene, reported: “Colonel Shoup is nervous. The telephone shakes in his hand. ‘We are in a mighty tight spot,’ he is saying. Then he lays down the phone and turns to me. ‘Division has just asked me whether we’ve got enough troops to do the job. I told them no. They are sending the 6th Marines, who will be landing right away.’”

The tactical situation on Betio remained precarious for much of the second day. Throughout the morning, the Marines paid dearly for every attempt to land reserves or advance from their beachheads. With the Marines holding a line on the island, the second day turned into an effort to cut the Japanese forces in two by extending the bulge near the airfield until it reached the southern shore. Meanwhile, the forces on Red 1 were instructed to secure Green Beach, the entire western end of the island. Major Michael P. Ryan, commanding the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines, led the effort, calling in naval artillery support to destroy Japanese pillboxes while they advanced.

Operations along Red 2 and Red 3 were considerably more difficult. The Japanese had moved in several new machine-gun nests during the night to slow the Marine assault. By noon, the Marines had brought up their own heavy machine guns and put the Japanese posts out of action. By early afternoon, the Marines had crossed the airstrip and occupied abandoned defensive positions on the island’s south side.

Around 12:30 pm, a small number of defenders on the extreme eastern end of the islet began trying to make their way across to the next islet, Bairiki. Portions of the 6th Marine Regiment, under Lt. Col. Ray Murray, landed on Bairiki, blocking the exit, while other 6th Marine units moved onto Green Beach. By the end of the day the entire western end of the island was in Marine control, as was an almost continuous line between Red 2 and Red 3 around the airfield aprons. Another group of Marines moved across the airfield and set up a perimeter on the southern side, up against Black 2 (Betio’s southern beach). Before being relieved by “Red Mike” Edson, Shoup sent a memorable message to Maj. Gen. Julian Smith: “Casualties: many. Percentage dead: unknown. Combat efficiency: We are winning.” For his stalwart command performance, Shoup would receive the Medal of Honor.

‘Banzai!’

Terrible as the invading Marines’ losses were, the defenders could not match the firepower and manpower being thrown at them. Indeed, as Shoup had reported, the tide had turned. Although on the morning of D-day + 1 there had been sufficient reason to doubt the ability of the committed Marine battalions to hold their meager gains, by dusk there was no doubt that the battalions and those reinforcing them would win the battle for Betio. All three battalions of the 2nd Marines had seized their D-day objectives. Three battalions of the 8th Marines were well short of their goals, but each had developed exploitable holdings, and each was in decent enough shape to advance on the morning of D-day + 3.

The third day of the battle for Betio saw the Marines consolidate their existing lines, thus facilitating the movement onshore of additional heavy equipment and tanks. During the morning the forces originally landed on Red 1 made some progress toward Red 2, but at some cost. Meanwhile the units of the 6th Marines on Green Beach, to the south of Red 1, formed up while the remaining battalion of the 6th landed. By the early afternoon of D-day + 3, the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines was sufficiently organized and equipped to take the offensive. At 12:30 pm, they moved out and were soon pursuing the Japanese forces across the southern coast of the island. By late afternoon, they had reached the eastern end of the airfield and formed a continuous line with the forces that had landed on Red 3 two days earlier. By evening, the Marines clearly held the upper hand. The remaining Japanese were either squeezed into the tiny amount of land to the east of the airstrip or were hunkered down in several pockets on Red 1 and Red 2 or near the strip’s eastern edge.

Aware of their situation, the Japanese formed up for a counterattack that started at about 7:30 pm. Small units were sent to infiltrate Marine lines in preparation for a full-scale assault but were beaten off by concentrated artillery fire and the assault never took place. That night, having lost Shibasaki to shellfire earlier in the day, the depleted Japanese defenders mounted an all-out counterattack. Screaming their all-too-familiar battle cry, “Banzai!” hundreds of Japanese soldiers charged Companies A and B of the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines. Lieutenant Norman K. “Hard Tom” Thomas, commanding Company B, led the repulse with heavy losses. When it was over, the Marines had suffered 45 dead and 128 wounded; the Japanese lost 325—all killed. Surveying the perimeter the next morning, Thomas said of his Marines: “Every damn one of them is a champion.”

At 4 am, the last Japanese assault finally took place; when the fighting ended about an hour later, another 200 to 300 attackers were found dead in front of the Marine lines, the vast majority killed by artillery fire. The Japanese now had little left for defending the atoll. Aware of impending doom, the last radio message from the garrison said: “Our weapons have been destroyed and from now on everyone is attempting a final charge. May Japan exist for ten thousand years!”

Seventy-Five Hours

Seventy-five hours after the first Marines waded and crawled onto the thin strip of Red Beach, Betio was declared secure. Some killing continued; last-ditch holdouts, hidden in bunkers or bypassed, potshotted unwary leathernecks before they were eliminated. A number of defenders blew themselves up rather than surrender. Of the 4,836 Japanese troops on Betio before the battle, only 17 Japanese soldiers and 129 Korean laborers were captured; the rest were killed. The Marines lost 990 killed and 2,391 wounded. Conquest of the remaining bits and pieces of coral that composed the Tarawa Atoll brought additional casualties, albeit on a much smaller scale than on Betio. The 2nd Battalion, 6th Marines landed on Bairiki and moved up the remaining islands in the atoll, conducting mopping-up actions until November 28.

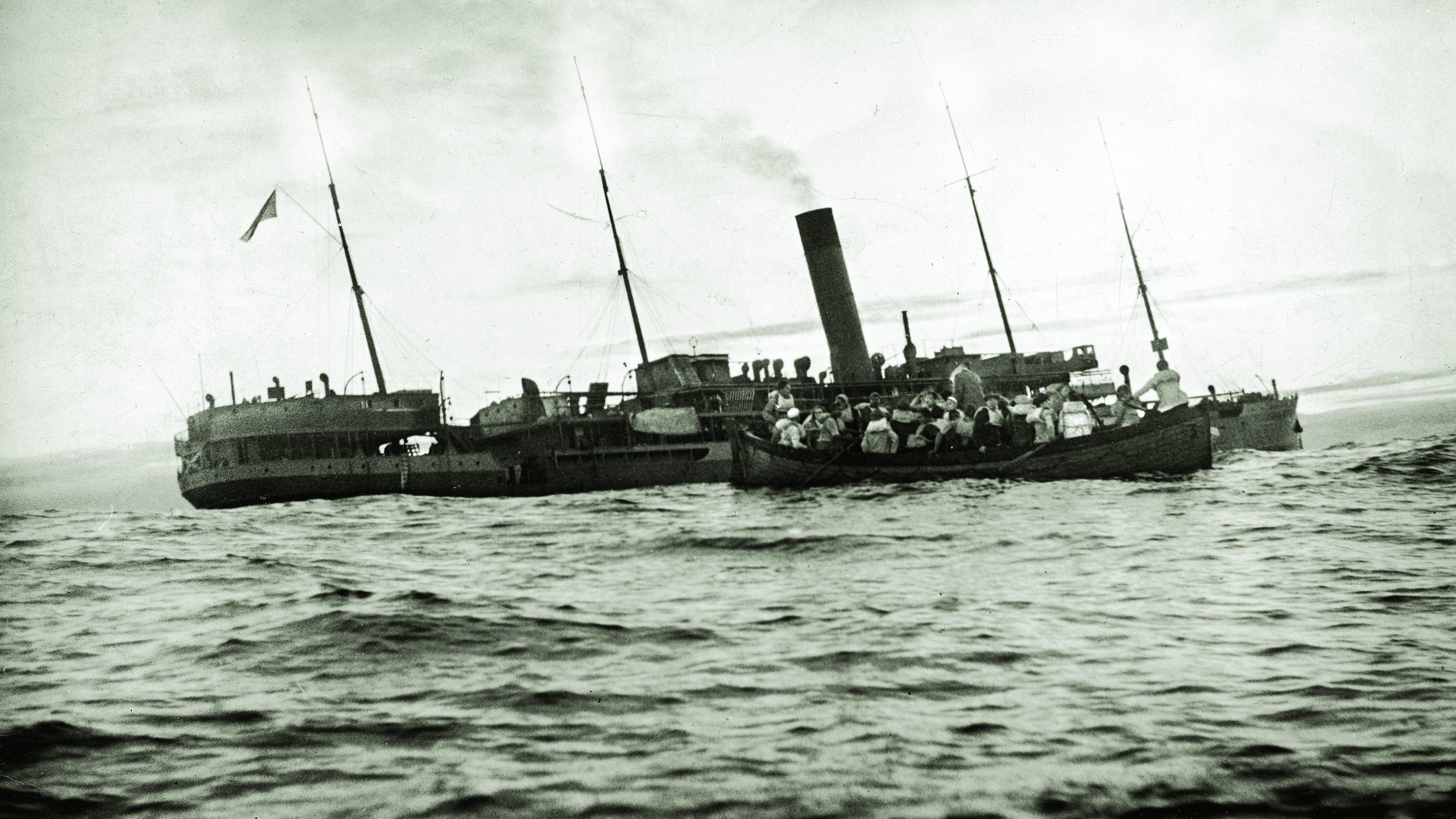

The bittersweet taste of victory turned sour less than 24 hours after Betio was declared secure. Because the conquest of Makin Atoll lasted four days instead of one, the naval task force supporting the 27th Infantry Division had remained on station in the nearby waters rather than steaming away from any Japanese submarines that might lurk in the area. In the early morning hours of November 24, the escort carrier Liscome Bay, in the company of several other vessels, prowled the area. The thin, four-ship screen around the Liscome Bay included the new destroyer Franks. When friendly radar detected unidentified aircraft, the admiral in charge dispatched Franks to investigate, punching a hole in the protection for the Makin task force’s three carriers. Another radio contact registered a surface vessel, but that blip vanished, indicating either the presence of a submarine that had just dived or perhaps a false image.

The convoy started to execute a planned maneuver just as Franks spotted a light on the water; an enemy airplane had dropped a floating flare to advise a Japanese submarine of nearby targets. At 5:13 am, a torpedo ripped into the Liscome Bay amidships. From a distance of almost three miles, Michael Bak, on the bridge of Franks, saw a gigantic explosion of fire soar into the sky after the initial detonation of the torpedo ignited the aircraft bombs stowed in the carrier’s hold. Fragments of steel, clothing, and human flesh showered the deck of the battleship New Mexico almost a mile away. Little more than 20 minutes later, the shattered hulk of the Liscome Bay sank, taking 642 officers and men down with the carrier, adding substantially to the total casualties suffered in Operation Galvanic.

Aftermath

The total of 687 U.S. Navy personnel killed brought the total American dead for the campaign to 1,677. Among those who perished was Dorie Miller, an African American steward who had shot down a pair of enemy planes at Pearl Harbor. In the segregated Navy, he died while still serving as a food handler. The heavy casualties sparked off a storm of protest in the United States, where the high losses could not be understood for such a tiny and seemingly unimportant island in the middle of nowhere. Nimitz, for his part, had no such doubts. “The capture of Tarawa knocked down the front door to the Japanese defenses in the Central Pacific,” he wrote.

Bloody as it was, Tarawa represented a swift and convincing victory. The hard lessons learned on Betio Island paved the way for continued successful amphibious assaults at pivotal battles such as Iwo Jima and Okinawa, and earned Tarawa a place in Marine Corps annals alongside such storied names as Belleau Wood, Guadalcanal, Inchon, and “Frozen Chosin.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments