By Keith Milton

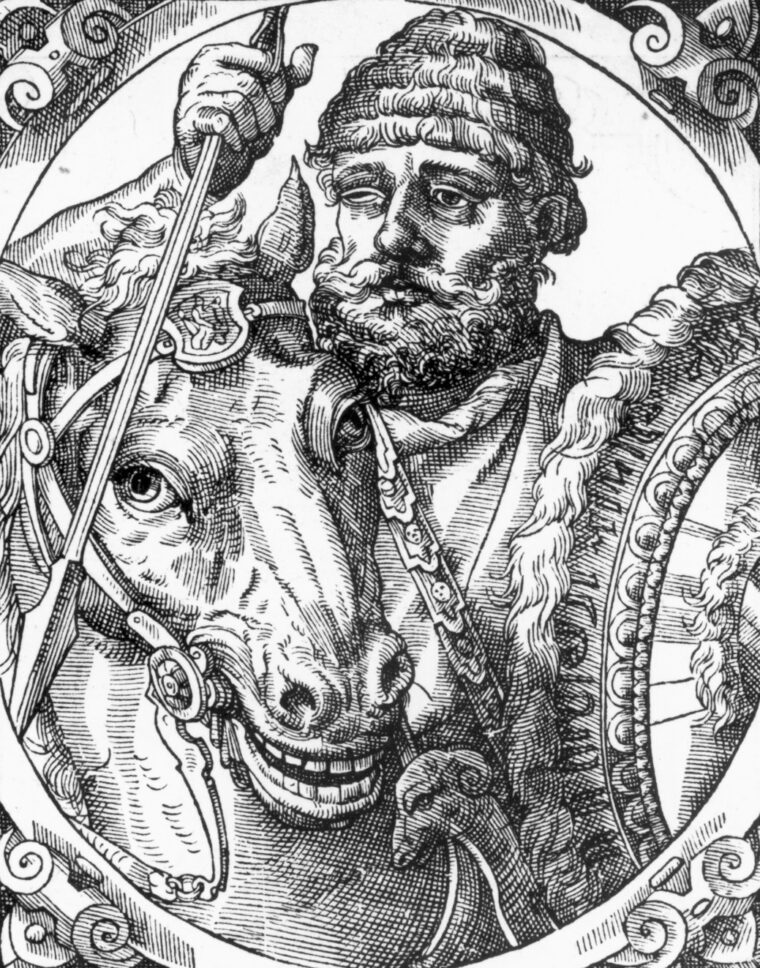

Gisgo, a commander in the Carthaginian army, sat on his horse nervously as he waited with other members of the staff for their general, the now-famous Hannibal, to complete his final inspection. Moving easily, like the superb horseman he was, Hannibal detected the apprehension of his staff as he rejoined them for a final appraisal of the situation. He had been outnumbered before by Roman legions, but had always managed to win victories through carefully laid traps, hidden ambushes, and other tactical means. Today’s battle would be a fully set piece, with everything out in plain sight. What disturbed the staff, and the entire Carthaginian army for that matter, was the size of the army facing them. Gisgo, seeking some kind of reassurance, decided to point out the obvious to Hannibal.

“Sire, they are more than twice our number!”

“I noticed that, Gisgo,” replied Hannibal, “but I also noticed something that you have apparently overlooked.”

“And that, Sire?” asked Gisgo.

“In that entire army, large as it is, there is not one man named Gisgo,” Hannibal replied.

Gisgo thought for a moment, and then began to laugh. Soon the entire group of officers was laughing. It proved to be infectious and moved through the other two lines and to the horsemen on either flank. The stodgy Romans opposite thought the entire Punic army to be mad and ordered their skirmishers forward. Hannibal’s jest had served to break the tension felt in his army and buck them up for the coming contest—The Battle of Cannae—his most spectacular battle in the Second Punic War. It would also prove to be one of the bloodiest days in the history of warfare.

The Bitter Taste of the First Punic War

A treaty to end one war very often contains the seeds of the next. Victors seldom feel magnanimous, especially if the war was long and costly, and the vanquished, smarting under the humiliation of defeat and the burden of harsh terms, can only look forward to future vengeance.

It was with this in mind that Hamilcar Barca took his nine-year-old son, Hannibal, into the Temple of Melquart, God of the City of Carthage, and placed his son’s small hand on the sacrifice at the altar. He then asked Hannibal to swear an oath that he would never be a friend of the Romans. Hannibal swore it, and although it would be several years before he could avenge his father’s defeat in the First Punic War, he would come as close as any man ever did to bringing Rome to her knees.

The First Punic War, like so many in history, was started almost by accident. Rome and Carthage were longtime former allies against Greece when Rome was still a small city-state within the borders of Latium.

Then in 264 bc, a dispute arose over which ally should assist the Mamertine rebels against Greece. One thing led to another, insults and incidents were exchanged, and the First Punic War was the result. (These wars were called Punic because the Romans called the Carthaginians “Poeni,” Latin for Phoenician. The word was later used as an adjective as well as a noun, when the Romans referred to “Punic faith,” “Punic trust,” and so on. It survives even today in its original pronunciation—“phoney”).

The contest dragged on for nearly 20 years, until the Romans built a huge navy, using a captured Punic galley as a model. They also made modifications that allowed their superior soldiery to be brought to bear, and defeated the Carthaginian fleet at the Aegates in 241 bc. Carthage sued for peace.

Hamilcar Barca, who with his guerrilla army had successfully harried the Romans in central Sicily for nearly five years, was recalled. Whether out of fear or respect, the Romans allowed him to depart with his army entire without passing under the yoke—an almost unheard of concession.

The other terms of the treaty were not so magnanimous, and placed Carthage on a near vassal status. A huge indemnity was also to be paid and 300 Punic noblemen were to stand hostage in Rome to ensure strict treaty compliance.

Carthage Turns its Attention to Spain

Hamilcar realized that the loss of Sicily and the islands of the Tyrrhenian Sea spelled the doom of Carthage unless Carthage could locate and exploit some other source of wealth. He looked to Spain.

Over the next five or six years, Hamilcar won many battles and brought nearly all of the Iberian peninsula under Punic control. Hannibal grew in stature and wisdom, learning his soldier’s trade from the ground up in his father’s camps. New Carthage (Cartagena) and Barca’s Town (Barcelona) became two of the largest trading centers in the Mediterranean as the new colony grew and prospered. Then, Hamilcar fell in battle in 230 bc, leaving command of the army to his son-in-law, Hasdrubal. Hannibal was only 16.

The army of Carthage grew steadily as more and more native tribesmen flocked to the Punic standard. By the time of Hasdrubal’s death by assassination in 221 bc, Hannibal could field an army of over 60,000 foot and 10,000 horse.

Hannibal Crosses the Pyrenees to Start the Second Punic War

All of this activity could hardly escape the notice of Rome, which had spies everywhere. When the Romans established a military mission at Saguntum, on the pretext of keeping the peace in Spain, Hannibal saw it as a breach of the treaty and demanded their withdrawal. When the Romans refused, Hannibal’s army lay siege to the city, and the Second Punic War was on.

Hannibal was in winter quarters with his army when the decision was made to invade the territory of Rome itself. His army had grown to nearly 100,000 and his Spanish cavalry had been beefed up by the importation of 5,000 Numidian horsemen from North Africa. He broke camp, crossed the Ebro, and headed for the Pyrenees. It was early spring, 218 bc.

Hannibal had sent envoys ahead to entice or bribe the fierce Celtiberian Gauls into allowing him free passage. They would have none of it and contested every foot of the way. This cost him many troops, and equally important, time. He knew that he must cross the Alps in mid-summer in order to use the passes the early winter snows would close. At last he began his ascent of the Pyrenees, leaving behind his brother Hanno along with 12,000 troops to guard the passes and protect his rear. He also released an additional 15,000 men to return home when they threatened revolt over the army’s destination.

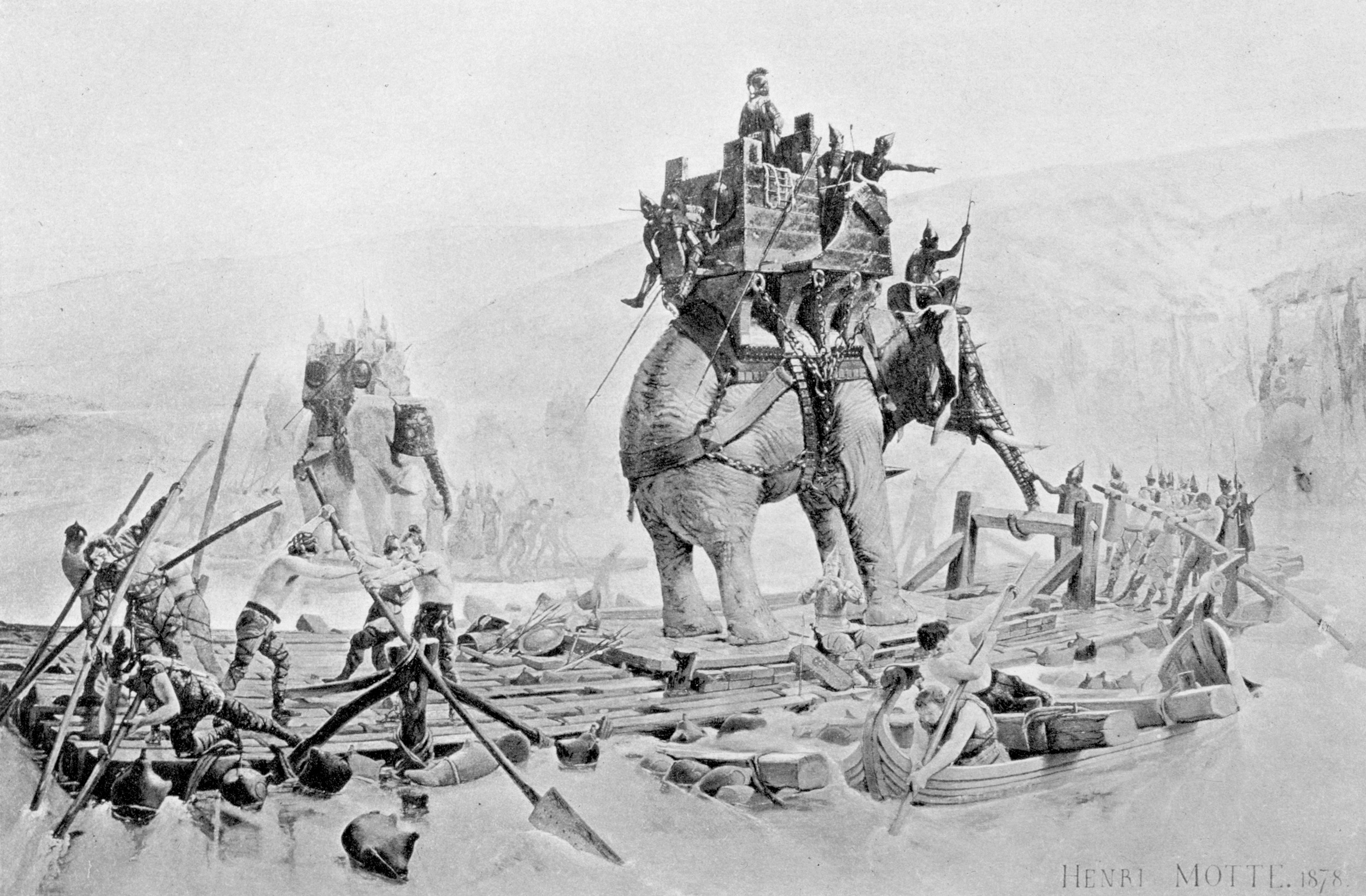

Hannibal crossed into Gaul with around 55,000 infantry, 9,000 horse, and all of the 37 elephants with which he had started. It was a much more manageable force than the one with which he had begun and was made up almost entirely of veterans. It was well that this was so, because they had a long, hard road ahead.

Rome, of course, had not been idle. The Republic was at that time operating under the Dual Consul system, and the Consuls elected for the year 218 bc were Publius Scipio and Tiberius Longus. The two cast lots for their assignments, with Scipio drawing Spain and Longus getting North Africa. The Senate had decided to mount attacks on both Carthaginian strongholds as soon as war was declared, but unrest at home had delayed the departures until midsummer.

Scipio had decided to make a mid-voyage stop at Marsalla (Marseilles) to reprovision and rest his men and horses before attacking Saguntum. It was here he learned that Hannibal had crossed the Pyrenees and was approaching the Rhone. Shocked, he immediately moved his legions along the coast and encamped on the east shore of the Rhone delta.

Meanwhile, Hannibal arrived at the Rhone about 45 miles north of the river mouth and began buying and building ferry rafts to move his army across. He also learned that two Roman legions were camped less than 50 miles downstream. Hannibal dispatched a force of light cavalry for a better look, and about half-way between the two camps they encountered a Roman patrol on a similar mission. The Romans chased the Numidians back into camp, reconnoitered the Carthaginian position, and reported back to Scipio. The Roman commander broke camp at once and speedily marched his legions north along the river bank, hoping to bring the Carthaginians to battle. When he arrived at the campsite he found it empty; Hannibal had given him the slip.

No One Would Cross the Alps in October, Would They?

Scipio immediately took ship for Rome, sending his two legions on to their original destination in Spain, under the command of his brother, Canaeus. Hannibal meanwhile began his long ascent of the Alps. Most Romans felt they had plenty of time to prepare their defenses, because, it now being late October, no one in his right mind would attempt a crossing this late in the year.

Hannibal’s army encountered all manner of hardships during the next four weeks. Wild mountain tribes continued their harassing tactics, and the weather moved against him. Food and forage ran short and parts of his army were near mutiny. Somehow, Hannibal held them together as they forged on, losing men and animals almost every day to freezing, malnutrition, and native attacks. But in the last week of October they emerged into the northern end of the Po valley and encamped for a well-earned rest. The cold and the wild Alpine tribes encountered in the crossing had cost Hannibal fully half of his army.

Scipio was shocked to learn that Hannibal had made good his crossing of the Alps and was now encamped in the Po valley. He sent word to his fellow consul Longus, now in Sicily with his two legions, to abandon the North African expedition and join him in an effort to defeat the invaders. All Rome was in a panic. Scipio hurried north to meet the threat, crossed the Po, and encamped near the Ticinius.

Hannibal Wins the First Battle

The first clash of arms was between cavalry units of brigade strength in which the Romans were outflanked and defeated, Scipio himself being badly wounded. Legend has it that he was saved from capture by the quick action of his teenage son, Publius Cornelius Scipio (later surnamed Africanus, and the only man ever to defeat Hannibal). The wounded Scipio then withdrew his entire army back across the Po to await the arrival of Longus and his army.

Hannibal’s initial success against Roman arms brought many tribes to his standard, and inspired nearly 2,500 Gallic auxiliaries to overpower their officers and leave Scipio’s camp to join him. By the time Longus arrived with his two legions to reinforce Scipio, Hannibal had enlisted enough Rome-hating Gauls and north Italian tribesmen to replace his Alpine losses. While he was inferior in infantry numbers, he enjoyed a two-to-one superiority in horsemen. Hannibal was also aware of the divided command system under which the Roman legions operated, and of the personality and temperament of each of the Consuls. Although Scipio still commanded on alternate days, his wound would prevent him from taking to the field. Scipio, who had grown cautious since his defeat at the Ticinius, advised delay. Longus was anxious for a victory before the Consular elections, which were coming up shortly, and was in favor of quick action. Hannibal decided to oblige Longus by attacking his camp.

Hannibal Attacks

He aroused his soldiers before dawn, saw that they were well fed and warmed by their campfires, their bodies oiled against the cold and their horses and elephants watered and cared for. Then he sent his light armed cavalry, the Numidian horse under Maharbal, to attack the Roman camp. Next, he moved the bulk of his army up the riverbed to take a position on the high ground beyond, but well within sight of anyone coming up the defile. On the way, he had his brother, Mago, see to the concealment of 2,000 men in the scrub bush and bracken on the sides of the small valley. His dispositions were completed just about the time that Maharbal and his Numidians finished their crossing and attacked the Roman camp.

Roused from their sleep by this quick thrust, the Romans struggled sleepy-eyed from their cots, pulling on armor as they went, trying to ward off spears and arrows, and expending their own missiles at the fast-moving horsemen. Longus ordered his own cavalry to engage the Numidians as he tried to assemble his legions. Slowly the Numidians gave ground as more and more Romans entered the action. They were under orders not to withdraw too quickly, lest the Romans give up the chase.

Soon the Romans were entering the icy Trebia in pursuit of their tormenters. As they staggered out on the opposite bank, Hannibal sent forward his slingers and pikemen to further disrupt the legions as they attempted to get into battle formation. Ignoring their losses, the Romans were soon advancing up the watercourse to meet Hannibal’s first skirmishers. Slowly the Gauls were forced back as the Romans advanced doggedly toward Hannibal’s army.

As soon as the forward elements of Longus’s legions engaged Hannibal’s main body, the war trumpets sounded and Mago’s contingent fell upon the Roman rear. Once encircled, their formations fell apart, Longus having no room to maneuver. Their only hope was to fall back to the river, which they did. Scattered into ragged groups, those who refused to surrender were cut down where they stood. Many drowned trying to regain the Roman camp as Hannibal’s heavy cavalry and seasoned Spanish infantry did their deadly work. Longus managed to save about a third of his original force as the Romans fell back to Placentia.

Rome Raises Two New Armies to Fight Hannibal

News of the defeat at the Trebia soon reached Rome and, coming so quickly after the Ticinius, caused the Roman Senate much concern. Unaccustomed to defeat, they set out at once to raise two new armies, the road to Rome now lying open. New consuls for the year 217 bc were elected, and once the new armies were levied, Gnaeus Servilius was assigned a spot at Ariminium on the Adriatic and the other Consul, Gaius Flaminius, was to cover the road to Rome from Arretium.

Early in the spring Hannibal moved his army westward to Colina, where he crossed the Apennines and descended into the marshes of the Arno. The passage was difficult and dangerous, but it gave him the tremendous tactical advantage of bypassing both Consular armies. He emerged into the central plains of Italy, plundering as he went to replenish his army’s supplies.

Flaminius, now left stranded at Arretium, had been seen by the Roman populace as barring Hannibal’s route to Rome. Now he was outwitted and outflanked. Furious, he broke camp as soon as he got the word of Hannibal’s maneuver and rushed headlong after his adversary, ignoring the advice of his staff. The cooler heads had wished to wait until they were joined by Servilius and his two legions, but Flaminius would have none of it. Even if he had not wanted all the glory for himself, he could hardly permit any further humiliation of Roman arms.

The Trap is Set for a Slaughter

Hannibal passed by Cortona and entered the defile of Malpasso on the north shore of Lake Trasimene, where he set up camp on the high ground at the northeast corner of the lake. The legions of Flaminius, following closely, encamped between Cortona and the north shore.

In the hills to the north, Hannibal stationed his Numidian light horse. Farther down, he placed the Gallic auxiliaries, and closest to the defile entrance, his Spanish and African heavy cavalry.

Early on the following morning, it all took place just as Hannibal had visualized. Drawn up in a column of march, the two legions made a line nearly two miles long. Four and six abreast, they came steadily on as Hannibal waited for the entire army to clear the defile. Then he gave the signal and the war trumpets blared. Like avenging angels, the Punic forces dropped down from the hills on the Roman left flank, the Numidians striking the van, the Gauls the center, and the heavy horse the rear where the Malpasso entrance was also sealed off. The Romans never even got into battle formation but fought as best they could, their backs to the lake. With no order in their ranks, they were cut to pieces, and in an hour, 15,000 legionaries had fallen with a like number taken prisoner. Hannibal lost but 1,500, mostly Gauls.

Hannibal now turned west to meet Servilius and his Consular army. He had the further good fortune of having the entire Roman scouting force of 4,000 horses defeated by Maharbal and his Numidians. Without his “eyes,” Servilius dared not move his army, and so was immobilized until his cavalry could be replaced.

Fabius Takes Command and Waits

News of this double disaster reached Rome and threw the city into near panic. Any other city-state of that period would have sued for peace after such serious reverses, but the stubborn Romans merely renewed their resolve. For the first time in their history, they elected a dictator by popular vote. Quintus Fabius, the elder, was selected, and he set about at once to strengthen the walls of Rome, burn the Tiber bridges, and raise a new army.

Fabius sensed that the major cause of Rome’s failures was amateur generals operating under a divided command system, and he resolved not to be drawn into a major battle. He would instead follow and harry the Carthaginians, attack their foraging parties, and cut off their patrols. He also sent word ahead of Hannibal’s line of march for the people to burn their granaries and destroy their crops. This was continued during the year following Trasimene and became known as “Fabian Policy,” and Fabius himself as “ The Cunctator” (Delayer).

Hannibal offered Fabius several chances to engage him, mostly under conditions apparently favorable to the Romans, but Fabius stood firm in his policy. Hannibal was forced to enlarge his patrols and foraging parties as Fabius continued to make life miserable for him.

Hannibal Escapes Fabius’ Trap

On one occasion near Casilinum, Fabius managed to trap Hannibal in his own snare. Instead of rushing in after Hannibal, Fabius merely reinforced both ends of the trap and decided to wait him out. Winter was coming on and Fabius knew that Hannibal would have to move soon or starve.

Hannibal had his Gauls gather a large herd of cattle together and prepare torches of faggots soaked in pitch. After dark, these torches were lashed to the horns of the cattle, and the cattle were moved up the hillside near where the Romans had set watch over the escape route. At a signal from Hannibal, the torches were lighted and the cattle driven over the hillside above the pass. Upon seeing this torchlight parade and hearing the racket, the Romans believed they were being outflanked and scrambled up the hill to meet the threat. Then Hannibal led his army through the unguarded defile to safety as the Romans stumbled among the panic-stricken cattle on the heights above.

Fabius, from his position that blocked the other way out of the plain, could see nothing in the dark and would make no move in spite of all the activity occurring near Casilinum. Hannibal had gauged his opponent correctly. The Delayer would wait until the cold light of dawn revealed exactly what was happening, but by then, it was too late. Hannibal made his way to Germonium where he captured a large grain store, fortified his position, and settled in for the winter.

The Roman Senate Doubles Down

The hotheads in Rome saw Hannibal’s escape as just one more example of the failure of Fabian Policy. They had chafed most of the year as two Roman legions meekly followed the Punic rabble around central Italy, pillaging and burning at will.

The Senate decided to return to the two-Consul system and to raise four more double legions. They had had enough. They would simply overpower this African upstart. The affront to Roman honor had gone on much too long. New levies on men and treasure were enacted as the Romans braced themselves for a supreme effort.

The Consuls elected for the year 216 bc were Aemilius Paulus, an old-line patrician, and Terentius Varro, a rabble-rousing plebian. They agreed on one thing, however; Hannibal had to go and the sooner the better.

Meanwhile, Hannibal left Germonium as soon as the grain ran out and moved south. He crossed the Aufidus and seized Cannae, thereby depriving the Roman army of another of its large grain stores. With plenty of food and water and his back to a handy hill, he decided to wait for Rome’s next move. It was not long in coming.

The same day they were installed as Consuls, Paulus and Varro moved their huge force southward to engage Hannibal. They had around 80,000 men—the largest army ever fielded by Rome.

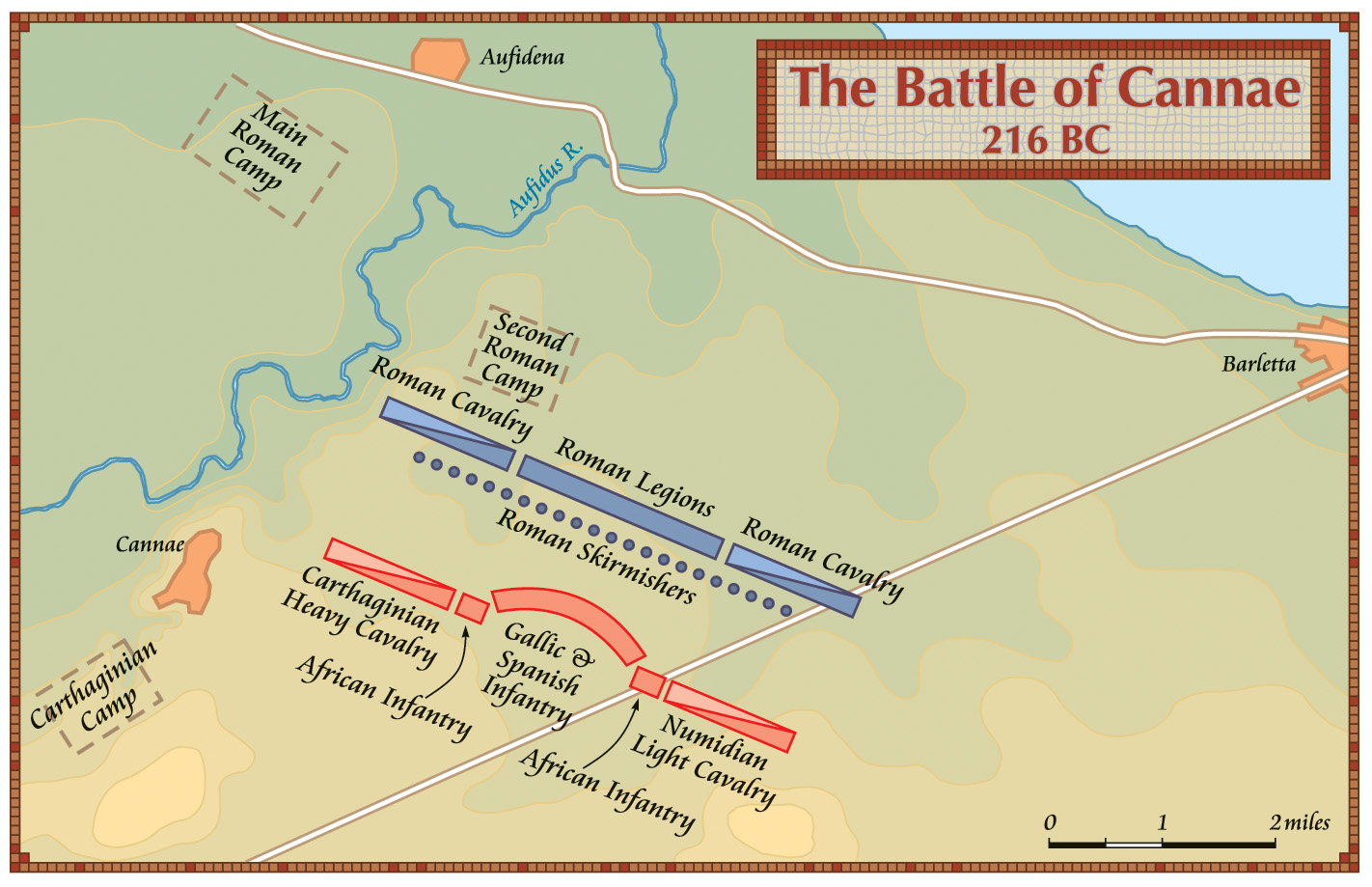

Hannibal, of course, being first on the scene, had choice of field. He moved his forces out of Cannae with one week’s stores and went about four miles south where he crossed the Aufidus and set up a fortified camp on the west bank. The ground was flatter there and was ideal for a cavalry action. The Romans arrived and made camp two miles north of the Punic camp. Because this put the Romans some distance from the river, they set up a second, smaller camp on the opposite bank and thereby secured their water supply.

The two armies eyed each other suspiciously for two more days as each made preparations. The small Roman camp was attacked by Maharbal and his Numidian horsemen on several occasions as Hannibal sought to interrupt his enemy’s water supply. It was June and the Italian summer was advancing toward the pitiless heat for which it is famous.

On Terentius Varro’s day to command, he moved his army across to the eastern bank and drew it up in battle formation. He knew that by getting between Hannibal and his food supply, Hannibal would have to move. The ground there was also more irregular and less suited for horsemen.

The Battle Begins

Hannibal then crossed with his army and proceeded with his preplanned dispositions. Both armies were placed more or less conventionally with a few exceptions. The Romans had their main body in the center, but with their maniple formation more tightly closed up than was usual. Varro had hoped to use this extra weight to hammer a hole in the Punic center, and he put Servilius in command of the main body. On the right between the rows of legionaries and the river, he placed his heavy Roman cavalry under the command of Paulus, his fellow Consul. On the left were the allies of Rome and their more lightly armed cavalry, which he himself commanded. His skirmish line was rather short and more dense than was usual so as not to interfere with his cavalry.

Hannibal’s main body was divided into three parts. The center was stretched forward in an arc-shaped bow and consisted mostly of Gauls and other auxiliaries. Each end of this bow was anchored to a formation of Spanish and African heavy infantry on either side. Facing the Roman heavy horse next to the river was the Punic heavy cavalry, and on the right facing the allied light horse was Maharbal and his Numidians. It was about at this moment that Hannibal made his jest to Gisgo and broke the tension in his outnumbered army. The Punic pikemen and slingers of Hannibal’s skirmish line moved out to meet the Romans.

As the skirmishers entered their melee, the cavalry on both sides came into collision. It was here that the superiority of Hannibal’s horsemen became evident. Hardened veterans were up against untried levies. Many of the Romans were unhorsed and forced to fight on foot. They did not lack courage, only experience. Soon, the Roman right wing began to collapse as the survivors fell back or took flight. The Spaniards and Africans caught up their horses and gave pursuit.

On the Roman left, Maharbal led the finest light cavalry in the world against Rome’s allies. Making quick jabs and thrusts, wheeling again and again like mythical harpies, they quickly outflanked the allies and put them to flight.

Meanwhile, the skirmish lines had melted into the main bodies as the Romans advanced. Seemingly unstoppable, their hammer blows bent the curve of the arc of the Punic center until it was nearly straight. Then it began to bend in the other direction as Hannibal’s center slowly gave way to the Roman thrust. The infantry on either side merely stood fast like walls of stone as the Gauls and Celts were forced inexorably back. The Romans continued to pour into this cavity like water into an empty pitcher until they were so tightly packed they could barely raise their arms. Then came the sound the Romans had learned to dread. The Punic war trumpets’ shrill cries burst through the hot and dusty air.

The Roman Legions are Put to the Sword

Hannibal’s heavy cavalry had regrouped and left it to Maharbal’s fleet Numidians to run down the retreating Roman horse. At the trumpets’ sound, they wheeled and took the legions in the rear as both wings of Hannibal’s heavy infantry now turned inward upon the mass of compressed Romans. Surrounded, the legions of Rome were systematically put to the sword. In less than two hours, the grisly task was done, as the tightly packed legionaries stood with barely enough room to fall as they were slain.

Varro, who had been so anxious for battle, led the remnants of the allied horse in flight and managed to survive. His fellow Consul and both Consuls from the previous year were all killed, along with 65,000 of the Roman host. The Carthaginians lost less than 7,000. It was the bloodiest single day in the history of warfare, before or since.

Often Hannibal brilliantly used topographical features to surprise and lay waste his adversary. At Cannae he used elements of his army itself to outwit and crush his enemy. The double envelopment on the plain of Cannae is still used in military academies today as an exceptional illustration of the principle.

If Hannibal was surprised when the Romans failed to sue for peace after Lake Trasimene, he was incredulous when the same thing happened after Cannae. They even refused to ransom or exchange the legionaries that had been captured, going against a long-standing tradition of that period. The Romans were not playing by the rules, even though their enemy controlled nearly half of the Italian peninsula, and the Romans had no army at all except for a few city garrisons. Fabius the Cunctator was again put in charge, and his policy reinstated. If they could not defeat Hannibal in the field, they would let him wither on the vine.

Livy, the famous Roman historian, said of Cannae: “Would you compare the disaster off the Aegates which the Carthaginians suffered in the sea-flight, by which their spirit was so broken that they relinquished Sicily and Sardinia and suffered themselves to become taxpayers and tributaries? Or the defeat in Africa to which this very Hannibal afterwards succumbed? In no single aspect are they to be compared with this calamity [Cannae], except that they were endured with less fortitude.”

Keith Milton, long a student of military history, turned to free-lance writing after his retirement in 1982. He spent World War II as a Merchant Seaman, completing 14 Atlantic crossings, two Mediter-ranean shuttles, and one Intercoastal voyage. He is the author of numerous articles and in November 2000 published a book about U.S. submarines in the Pacific during WWII.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments