By Shippen Swift

Looking at a 1917 newspaper photo of Frederick Funston, barely 5 feet 4 inches tall and weighing just a biscuit over a hundred pounds, today’s reader would wonder whatever made U.S. President Woodrow Wilson select such a tiny fellow as leader of the American Expeditionary Force into France—when and if the United States was to involve itself in World War I.

But Funston, who was born in 1865, cast a large shadow during his brief life—rising from raw recruit with the revolutionary forces of Cuban generals Calixto Garcia y Iniguez and Maximo Gomez, to a major generalship in the Regular U.S. Army. Beginning in his teens, Funston lived the adventures of a dime novel hero and survived an exceptional amount of combat.

Son of a former Union Army artilleryman, Ohio-born Funston moved, while still an infant, with his family to the primitive town of Iola, Kans. Funston’s mother imported the first piano as well as the first bathtub into Iola. A neighbor thought the tub was a new kind of coffin and asked who had died.

Funston’s father—a 6-foot, 200-pounder with the vocal chords of a giant—was a politically oriented successful farmer. Elected to Congress, his loud voice earned him the nickname “Foghorn,” although for obvious reasons he preferred what his constituents called him—“The Farmer’s Friend.” He was a strict teetotaler, but his son “had a throat like a dry crust” that needed alcoholic attentions, which consequently set a wall between the two.

Young Fred’s boyhood was normal for the times—fishing and hunting outscoring his interest in schoolwork—but after Iola High School he tried for an appointment to West Point. Ironically, but perhaps understandably, he failed to qualify academically as well as physically.

The Beginning of Funston’s Uncanny Luck

So he went to the University of Kansas where his grades were less than remarkable but where his ability to be in the right place matched his uncanny luck at being there at the right time. For example, among the friends he made at university was the young William Allen, later to be a world-famous editor who, by the early 1900s, became a personal friend of President Theodore Roosevelt.

The beginnings of this career gave no hints of Funston’s latent military talents, but his early activities were tributes to his extraordinary pluck. For instance, during a summer vacation from college, Funston took a job as a railroad ticket collector on the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad, a line noted for the unruly behavior of its cowboy passengers. One of them once refused Funston’s request for his ticket, pointing out that his revolver was ticket enough. Funston said, “Good! That’s good,” and went on his way. But minutes later, he returned with a cocked weapon of his own, saying, “I’ll take your ticket now, if you don’t mind,” and did so.

Initially unimpressed with his diminutive size, the rough crowd that rode his route saddled him with the disparaging nickname of “The Toy Collector.” But by the end of his tour, his nickname had changed radically. All along the tracks, Funston became known as the “Human Marmot”—a man with “death in his right fist and lingering illness in his left!”

Obviously, a spirit like Funston’s chafed at conventional college life—he had no aptitude for organized study but spent free hours in the library absorbing what he found interesting. He also disregarded the Kansas temperance laws, and after a row with Foghorn, young Fred persuaded him to pull Washington political strings and secure him a botanist’s job with the Department of Agriculture. A few months’ pleasant apprenticeship in the Montana grasslands preceded nine months of broiling hell in California’s Death Valley, enduring temperatures of 127 degrees.

The following year, 1892, Funston went to the other extreme on assignment in Alaska’s frozen mountains where his activities established a record for the longest snowshoe trip ever accomplished by a white man. And in 1894, his astonishing solo canoe paddle of 1,100 miles down the Yukon River to the sea moved his friend White to write: “No bugles sounded on his return. Yet for continued hardships, unceasing danger and uninterrupted adventure, probably this trip has been unexcelled by any other on this continent in a century.”

When the Iola Register published accounts of his journeys, Funston had a brief fling as a newspaperman. It ended when, in the editor’s absence, he substituted his own opinions for what was supposed to appear on the front page.

Still restless in 1896, he drifted to New York City trying to raise capital for a coffee plantation venture in Mexico. And once again, the right place coincided with the right time. Passing the famous auditorium known as Madison Square Garden, Funston saw a notice that former Union Army General Daniel Edgar Sickles was inside whipping up an enthusiastic crowd over the question of freedom for the Spanish island colony of Cuba.

Cuba Libre Convert

Sickles, who lost a leg leading a corps at Gettysburg in 1863, recently had been American Ambassador to Spain, and it was said that in this capacity he’d had the gall to order the Spaniards to leave the island. True or not, Sickles had then been ordered to leave Spain.

Curious, Funston strolled in to hear what Sickles had to say.

The Funston who emerged several hours later was a convert to “Cuba Libre!” and was determined to become an active participant in the effort to bring this about.

Somehow wangling an introduction to Sickles, Funston learned that the Cuban Patriot Army valued a man with knowledge of field artillery. Consequently he bought a book on the subject, boned up on it, and presented himself to Cuban exile headquarters. In the interim, he’d also taken practical instruction on the operation of the Hotchkiss 12-pounder breech-loading cannon from an arms dealer, and within short order, the son of Union Army artilleryman “Foghorn” Funston became Ordnance Advisor to the Cuban Patriot Army.

In that capacity—although his only experience with live artillery firing had been hearing a 21-gun salute for then U.S. President Rutherford Birchard Hayes at a state fair—he conducted a live demonstration for his Patriot Army superiors with the as yet unproven Sims-Dudley dynamite gun. Setting up on a remote Long Island beach a few miles east of New York City, the group watched the weapon erratically lob shells into Long Island Sound. The resultant hundred-foot geysers in the vicinity of a passing excursion boat understandably created on-board panic and terminated the demonstration—but the sale was closed.

The gun and Funston went off to Cuba, and after two years of constant combat, Funston returned to Kansas broke and in poor health. He’d contracted malaria, been shot through both lungs, one of his arms had been snapped, and both legs had been crushed under a dead horse, causing a painful hip abscess.

Despite these agonies, Funston still managed to be one of the first volunteers when the United States finally went to war with Spain in April of 1898. Aware of his Cuban experience, Kansas Governor John Leedy gave the 33-year-old Funston a colonelcy in one of the three regiments the state was raising from scratch, the 20th Kansas Volunteers. Significantly, the 20th’s ranks included several privates who’d resigned commissions in the National Guard because they figured a man with Funston’s Cuban experience would be among the first ashore when the island was invaded.

“The Smartest Thing I Ever Did in My Life”

But he wasn’t. The debarkation port of Tampa, Fla. was a chaotic monument to mismanagement, and there weren’t enough transport ships to accommodate more than 60 percent of the assembled troops. While other officers—such as Rough Riders Theodore Roosevelt and his colonel, Leonard Wood—reaped lifelong glory from the brief Cuban fight, Funston had to lead his frustrated Kansans in the other direction—to occupation duty in the former Spanish colony in the Philippine Islands.

En route, however, following an uncomfortable train ride to San Francisco, Colonel Funston found reward in the West. After a six-week courtship, he married a local girl, Eda Blankart—an act that he characterized as “the smartest thing I ever did in my life.”

But within days of his marriage, bridegroom Funston was at sea—bound for the Philippines and events that propelled him into the national spotlight for the rest of his days. The 20th Kansas was part of the U.S. force—under Maj. Gen. Arthur MacArthur—sent to the islands to ease the transition from the iron rule of the defeated Spaniards to eventual self-government.

The Filipinos, however, mistakenly imagined immediate self-government after 400 years of the Spanish yoke and were deaf to warnings about the vacuum created by the Spaniards’ departure. With no experience in governing their asset-rich homeland, they could easily lose it to the colony-hungry Japanese, or the Germans, or even the British, who were said to have “conquered half the world in a fit of absentmindedness.” To forestall any of this, the administration of U.S. President William McKinley—whom Theodore Roosevelt had earlier denounced as having “the backbone of a chocolate eclair”—authorized the questionable task of occupying the Philippine Islands “for their own good.”

Freddy’s Fast Express

Because this caused objection, upheaval, and armed rebellion, the 20th Kansas put in a year’s worth of combat on the main island of Luzon. Their spirit is best exemplified by Funston’s answer to General MacArthur when asked how long the volunteers could hold a certain critical position under fierce attack: “Until the regiment is mustered out, General!”

Eventually the 20th—proudly nicknamed “Freddy’s Fast Express”—did return to Kansas. Funston, however, reembarked for Luzon. In addition to his leadership and bravery—he had won the Medal of Honor for personally leading six men on a perilous river crossing under hostile fire—he displayed remarkable administrative ability.

But Funston—a left-hander who for some reason wrote with his right hand—was too unconventional to be content behind a desk, and his biggest success came when he captured the Filipino insurgent leader Emilio Aguinaldo.

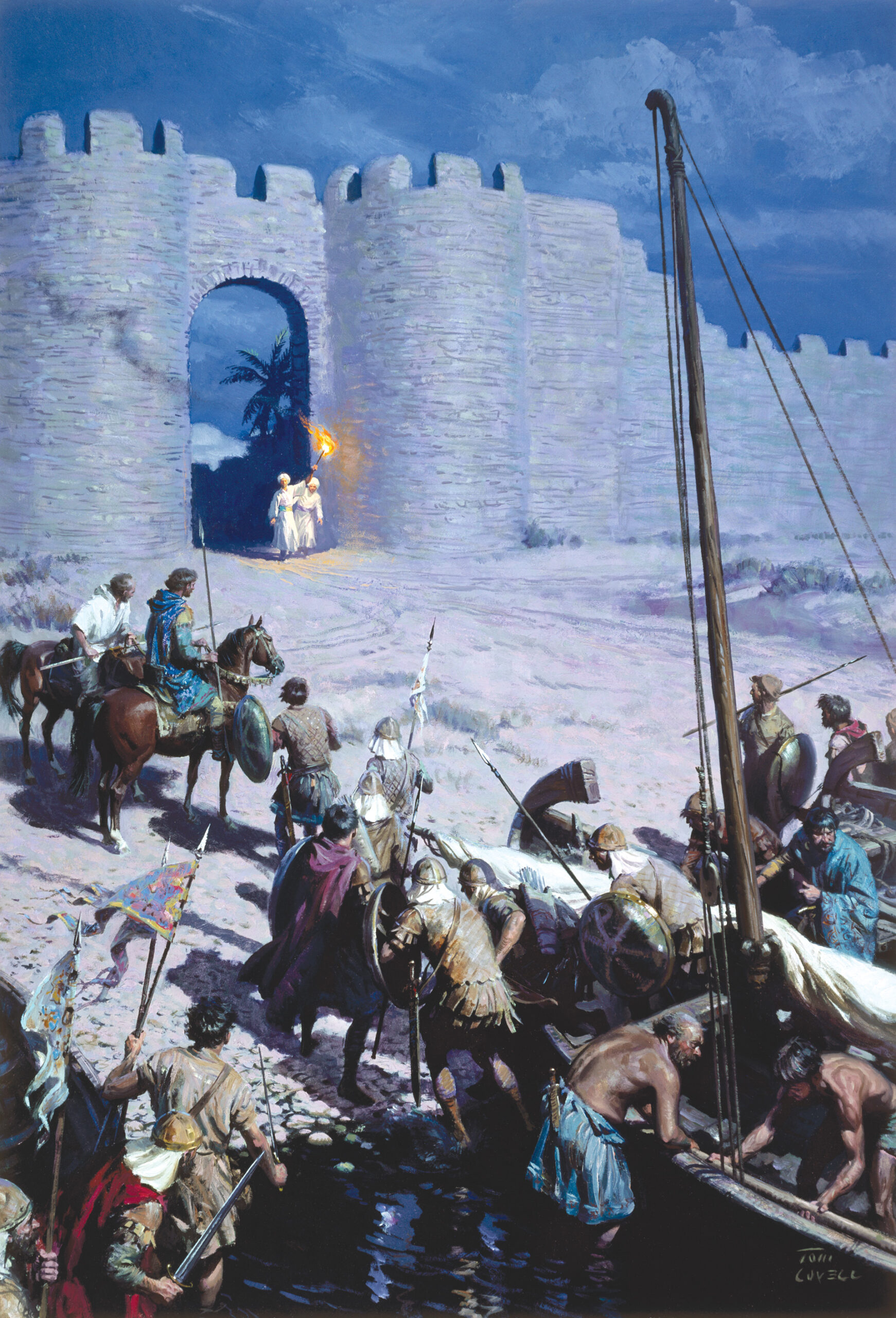

The brains behind the insurgents’ backbone, Aguinaldo had holed up in a remote jungle clearing in northeast Luzon and his capture was the stuff that made world headlines. In a ruse to snatch the rebel, Funston had been assigned the role of a captured American while a troop of anti-insurgent Filipinos had posed as his captors. Together they traveled through one of the world’s true tropical hells on a bunch of counterfeit safe-conduct passes to the mountain hideaway.

The scheme worked and with Aguinaldo out of the way, the fighting—at least on Luzon Island—tapered off. A grateful President McKinley had Congress confirm Funston as a Regular Army brigadier general, jumping him over the heads of at least a hundred senior Regular Army colonels. However, the disguise tactic and the revelation that Funston’s group had of necessity begged an emergency food supply from the unsuspecting Aguinaldo caused ethical eyebrows to raise. In addition, Funston attracted the peevish enmity of satirist Mark Twain. An ardent proponent of anti-imperialism, Twain published a viciously personal, sarcastic blast against Funston. Although stung, the new brigadier general limited his comments, merely remarking that Twain’s comments were “lady-like.”

Returning to the United States, Funston became second-in-command to Maj. Gen. Adolphus Washington Greeley, head of the Regular Army’s Department of California. Once again, on April 18, 1906, Funston’s uncanny talent for yoking the right place with the right time put him in the spotlight during the famous San Francisco earthquake and subsequent fire.

Funston Builds His ‘Take Charge’ Reputation

General Greeley was off in Washington, DC, at his daughter’s wedding, so Funston was in temporary command when the enormous quake struck. With water mains ruptured, the subsequent fires were uncontrollable, and with telephone lines out and telegraph wires down, there wasn’t a communications thread to the outside world. Funston left his home on foot, reached the main army stable, and sent off riders with orders for all troops to leave their barracks and place themselves at the disposal of the city’s police chief.

Eventually, though, Funston took complete charge, and while he was praised for firefighting and looting prevention, his decision to dynamite whole blocks of buildings to create firebreaks caused an uproar. His actions contained the fires, but the cost was four and a half square miles of dynamited devastation.

Nonetheless, his actions reinforced his reputation as a “take charge.”

But no subsequent take-charge opportunities came along until 1914, when in April an ugly incident developed at Tampico, a port on Mexico’s east coast. It started when 14 U.S. sailors on shore leave were briefly arrested. After their release, U.S. President Wilson saw an opportunity to embarrass and possibly oust Mexican dictator Victoriano Huerta. Consequently, Wilson refused to accept the man’s official apology unless Huerta publicly saluted the American flag. When this demand was refused, Wilson ordered U.S. Marines to storm the principal Mexican east-coast port of Vera Cruz—an action costing 18 American lives.

This ignited American public opinion, so the president selected Funston to take charge of Tampico’s occupation. The Tampico Funston took charge of was more of a squalid mess than a major city. To maintain order, he had to use his troops as police before setting to work sanitizing the place.

11,000 Hostile Mexicans, and Other Challenges

Understandably the next seven months were difficult, but the way he handled them eventually earned him a belated major generalship (he’d been passed over twice) and, significantly, he was back in the public eye as a hero. For although keeping the peace was tough enough when faced with 11,000 hostile Mexicans, there were many other challenges worthy of Funston’s energies.

It just so happened that while Funston was in Vera Cruz, World War I broke out. In the harbor was the German light cruiser Dresden, and French merchant sailors also in port brawled with her crew. Acting fast, Funston ordered Dresden to put out to sea at once, and held the visiting British Navy cruisers Berwick, Bristol, and Suffolk in port for 24 hours, thereby heading off an international incident.

At the end of the U.S. Vera Cruz occupation in November of 1914, Funston’s coolness and good judgment prevented another ugly incident. For as the last U.S. troop ship—ironically the Kansas—glided out of the harbor, a Mexican cavalry unit galloped up to the dock. Displaying a large Mexican flag, and taunting the Americans with shouts and rifle fire, they created the impression that Funston was retreating.

“Clark,” Funston said quietly to his aide, “if they are firing at us we will go back. But,” he shrugged, “so far they are just firing in the air.”

His major general’s two stars put Funston in command of the U.S. Army’s Southern Department based at San Antonio, Tex., and with the war in Europe heating up, there was a strong move in Congress to reactivate the rank of lieutenant general, dormant since the Civil War. The idea was to place the three stars on Funston’s shoulders, but wisely he declined the honor, saying it would humiliate those senior to him.

Nonetheless, President Wilson had his eye on him, and Funston’s rapid response to the famous March 1916 Pancho Villa raid on Columbus, New Mexico, made it clear who’d be in command if the U.S. Army got involved in the European war. Although Brig. Gen. John J. Pershing was in direct command of the troopers chasing Villa some 600 miles down into Mexico—and hence garnered the publicity—overall command responsibility was Funston’s.

Tragically, this heavy responsibility and the long hours involved exacted a toll. On the evening of February 17, 1917 Funston collapsed in the lobby of San Antonio’s St. Anthony Hotel and died almost instantly of a heart attack.

“In All His Dealings, the Element of Greatness Showed Forth Unwaveringly”

So ended the career of a most remarkable man. At a time when the miniscule U.S. Regular Army functioned like a private club for West Point graduates, Funston was one of a non-West Point trio who achieved two-star rank in an unorthodox manner while winning the U.S. Medal of Honor in the process. The others—Arthur MacArthur and Leonard Wood—were both brave and capable, but were not above using political influence for career enhancement. Funston, on the other hand, once faced political censure. As noted earlier, his friend William Allen White had become close to President Theodore Roosevelt. Consequently, when Roosevelt became enraged by Funston’s public mutterings about political appointee-governor William Howard Taft’s interference in the Philippines, he passed word to White.

Deeply worried, Funston’s old pal admonished his friend to keep his mouth shut against the tide of words coming out of it and the tide of liquor going into it. But, always a man with a sense of humor, Funston ruefully responded: “Oh, Billy, look not upon the gin rickey when it is red and giveth color to the cup, for it playeth hell and repeat with poor Timmy [Funston’s college nickname].”

After Funston’s passing, White wrote the most poignant eulogy: “In all his dealings, the element of greatness showed forth unwaveringly. He was simple and direct. He knew no simulation or poses. He never walked on stilts. He despised cant and canters. He was as dashing as Little Phil Sheridan; as unique and picturesque as the slow moving, taciturn Grant; as charming as Stonewall Jackson; as witty as old Billy Sherman; and as brave as John Paul Jones.”

A Self-Evolving Circle

Taking a last look at the whole Funston picture, two curious incidents close the book and echo the poet Emerson’s observation that: “The life of man is a self-evolving circle.”

The first involves Major General Arthur MacArthur, Funston’s commanding officer in the Philippines. Funston’s baby son had a silver christening cup engraved “Arthur MacArthur Funston/From Arthur MacArthur/1902.” This child died as a youngster, but 40 years later, when Arthur MacArthur’s young grandson Arthur MacArthur IV fled from Corregidor with his mother and his famous father Douglas, it was reported that he had the Funston baby’s cup in his hand.

And finally, the night the duty officer—a public relations officer—at Secretary of War Newton Baker’s office got word of Funston’s death in San Antonio, he sped to the secretary’s Washington, DC home with the news. Because Funston had already been selected to command all the U.S. forces if they went to France, the stunned Baker began thinking out loud. “Whom are we going to select to fill the post?” he wondered.

Without a pause, the public relations officer suggested the name of a newly promoted major general … “Pershing!” he said.

That public relations officer was a newly promoted major—Douglas MacArthur.

Great story! General Funston was truly one of a kind. We sure could use some of his type today.

It shows that height and weight does not make a soldier great. But a motivated individual and being in the right place at the right time for greatness to emerge.