By Robert Barr Smith

Throughout World War II, the British Admiralty’s deepest concern was the all-important shipping lanes that supplied their island fortress. If they failed to protect them, the British Isles would starve, and Hitler would reign triumphant. The Atlantic lifeline was very long and very fragile. There were plenty of merchant ships to keep Britain in the war; the critical need was escorts—warships—to protect the vital convoys and screen the heavy units of the Royal Navy. Early in the war there were never enough of these. A number of Royal Navy destroyers—already too few—had been sunk or damaged during the evacuation from Dunkirk in the summer of 1940, during the German invasion of Norway, and from other causes.

In September 1940, the United States would transfer 50 old four-stack destroyers to Britain in return for base rights on British possessions in the Caribbean. They would be a great help, but many more ships were needed. Shipyards in Britain, the United States and Canada hummed with activity. Over time, they would produce scores of destroyers, sloops, and corvettes for the hard-pressed Royal Navy. But until those ships arrived in numbers, the Admiralty would any tools that were available.

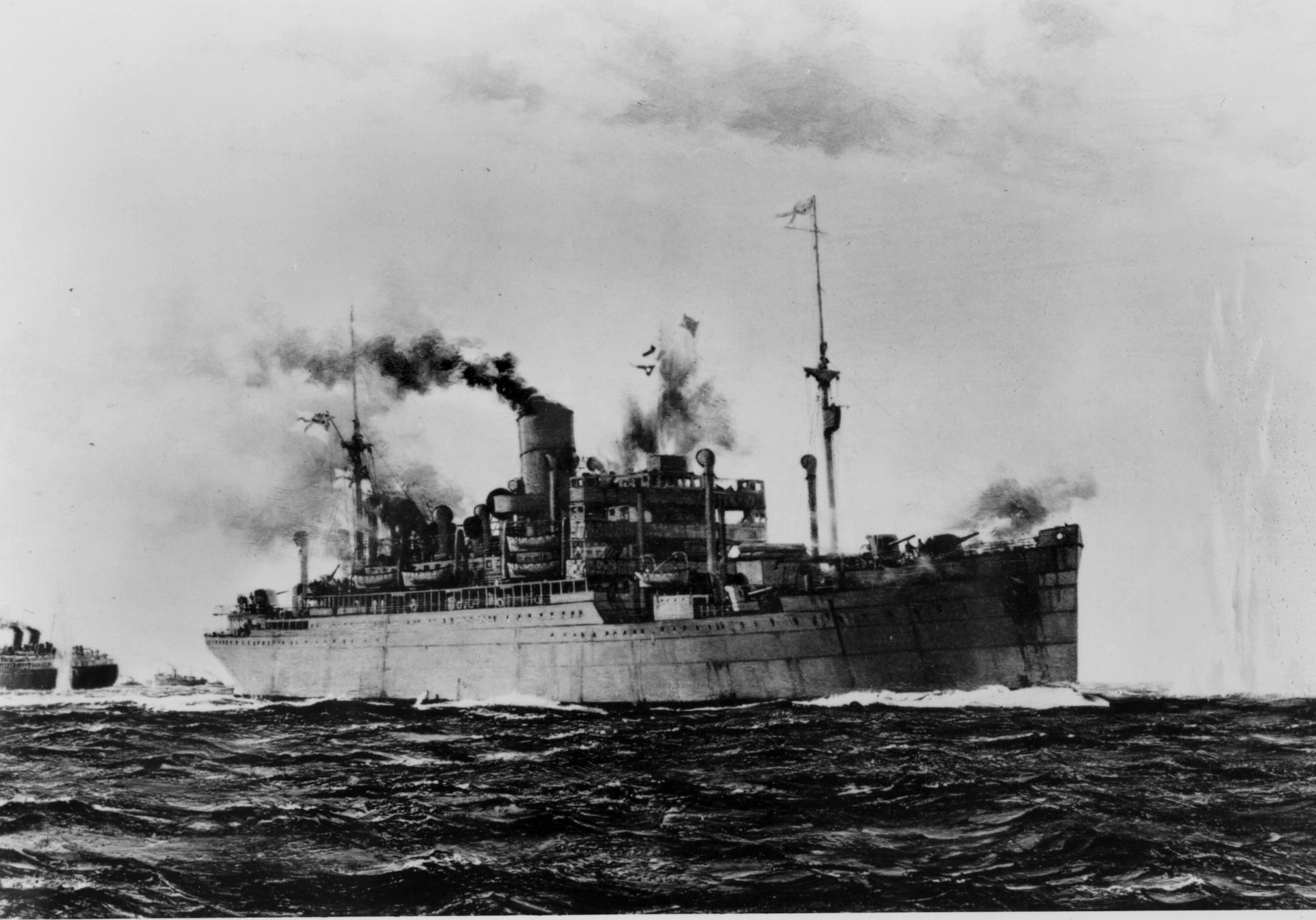

And so the Royal Navy commissioned auxiliary cruisers, civilian ships equipped with old weaponry and minimal amounts of other gear. They were manned by Navy crews, most of them reservists, and sent to sea. They would provide at least some semblance of armed escort to the armada of merchantmen that was the lifeblood of the British Isles. And they would serve other purposes as well: watchful eyes in the wild, frigid waters north of Great Britain, the remote, foggy avenues through which German surface raiders would have to pass to reach the North Atlantic.

Outgunned, Out-Armored, and Antiquated

Generally, these auxiliary cruisers had been liners by trade in their civilian days, traveling on their lawful errands to the United States, the Far East, and India. They were reasonably fast and long ranged, but high sided, virtually unarmored, and lacking the complex compartmentalization that gave warships their ability to absorb damage and still keep fighting. With all kinds of weaponry in short supply, they could be equipped with no more than old guns and minimal ranging equipment.

Still, they were better than nothing, especially since the Germans were expected to use surface raiders to prey on British shipping, and that included civilian ships converted into commerce raiders. The Kriegsmarine did indeed field a number of raiders in this war as well. Among the more famous were Kormoran, Pinguin, Thor, Atlantis, and Komet. They packed substantial armament. In her last fight, Kormoran was able to sink the Australian light cruiser Sydney, although Sydney took the German with her.

Still, an auxiliary cruiser might expect to fight such a raider on approximately even terms, at least to put up enough of a fight to hold the raider away from a convoy. In mid-September 1914, for example, Cunard liner Carmania, converted to an armed merchant cruiser, fell in with German raider Cap Trafalgar off the coast of Brazil. Carmania was outgunned by her enemy, but her own shooting was superb. Though she took repeated hits in her superstructure, Carmania’s guns hit the German again and again at the waterline. Cap Trafalgar broke off the action and ran for shelter, sinking two hours later.

And so, early in World War II, a number of British liners were converted to merchant cruisers. Some of them were lost, several to submarines, against which they had little defense. That was the fate of Laurentic and Patroclus west of Ireland in November 1940, and Salopian off Cape Farewell near Greenland the following May. Two of the ex-liners, Rawalpindi and Jervis Bay, met the ultimate test, a head-to-head fight against cruisers or pocket battleships of the German Navy. Vastly outgunned, with antique rangefinding gear, lacking any armor worthy of the name against the big German guns, the merchant cruisers’ ends were preordained. But they did their duty to the end in the bitter waters of the North Atlantic, and a lot of cargo ships and merchant seamen survived because of their heroism. This is how it happened.

Encountering Scharnhorst and Gneisenau

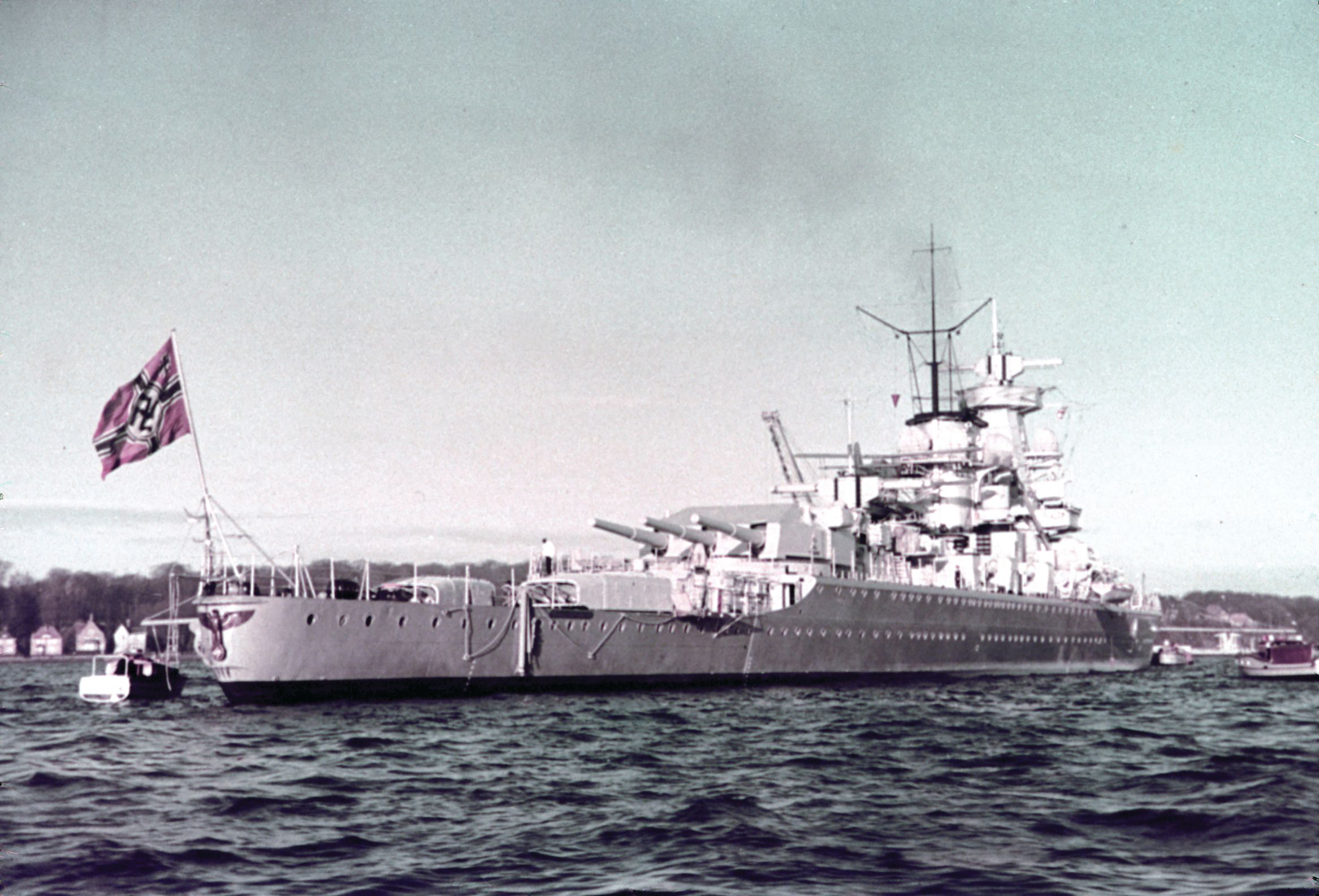

Rawalpindi could not have met more trouble unless she had run into super battleships Tirpitz and Bismarck, a pair that never went to sea together. What this vulnerable liner had encountered were sister ships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, fast 26,000-ton battlecruisers protected by heavy armor, 12 inches covering their turrets and the amidships portion of their hulls. They carried 11-inch main armament, nine tubes in three turrets, plus a dozen 5.9-inch guns and a formidable collection of antiaircraft weaponry.

Under the command of Vice Admiral Wilhelm Marschall, these two monsters sortied from Wilhelmshaven on November 21, 1939, sailing northward through a brutal sea and winds of gale force and higher. The foul weather at least blinded British air reconnaissance, especially as the two big ships ran the dangerous 130-mile-wide passage between the Shetland Islands and the Norwegian coast.

For a day and a half the two battlecruisers crashed through wild seas, heading into the storms and darkness of the north, their goal the passage between Iceland and the Faroe Islands and the picket line of smaller British ships that watched that strategic gap. The big ships’ mission was to “roll up enemy control of the sea passage … and by a feint at penetration of the North Atlantic appear to threaten his sea-borne traffic.”

Late on the 23rd, only an hour or so before the stygian gloom of the arctic night came rushing down, Scharnhorst spotted a large ship through the murk and notified Gneisenau. Both ships turned toward the stranger, which seemed to be making maximum speed away from them. Although Kurt Hoffman, captain of Scharnhorst, was reasonably sure he had sighted an armed merchant cruiser, he still took the precaution of signaling with his big searchlight to the stranger. “Stop,” he flashed. “What ship? Do not use your wireless. Where from and where bound?”

“FAM,” came the reply, sent repeatedly. The response meant nothing to the Germans, who thought that it had to be some sort of recognition signal, or perhaps a code for the vessel’s name. At last the battlecruisers got near enough to make out guns on the deck of the big ship, a liner, and to see that she was dropping smoke floats overboard. At just after 5 pm, Scharnhorst’s big guns belched fire, sending nine shells howling toward the strange ship. Almost instantly the target replied, and six-inch shells burst close alongside Scharnhorst.

Captain Kennedy’s Error

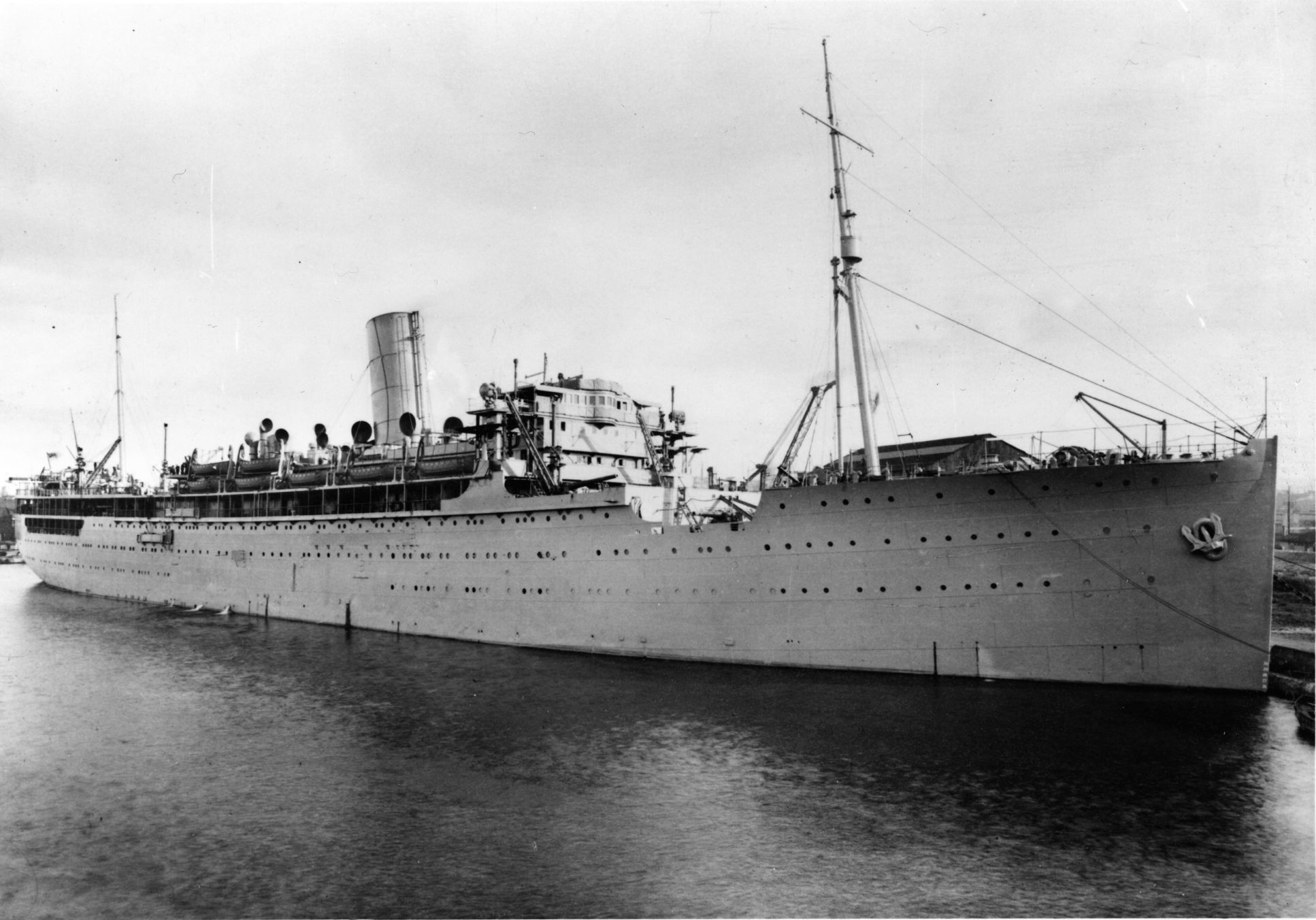

The stranger was British, HMS Rawalpindi, a 16,697-ton liner, one of four sister ships built in the mid-1920s for the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company. In happier times, she and her P & O sisters sailed the long route from Britain to India via the Mediterranean, Suez, and the Red Sea. Now armed with eight old 5.9-inch guns, she was part of the Northern Patrol, manning the picket line of ships stretched across the malignant waters of the 200-mile gap between the Faroes and Iceland.

Her captain was Edward Kennedy, a 60-year-old Royal Navy officer who had come out of retirement to command Rawalpindi. Her ship’s company of 306 was the usual mix of Royal Navy regulars and reservists, plus 126 members of her peacetime crew who volunteered to stay with her when she was pressed into wartime service. On November 23, she was about 95 miles east of Iceland, bucking a rising sea and a howling northwest wind that was getting stronger by the moment. The temperature was already below freezing, and it was falling. Hail banged intermittently against the windows of the bridge. The Iceland-Faroes gap was as ugly as usual.

Kennedy was concerned that his improvised warship might meet the pocket battleship Deutschland; Admiralty intelligence believed that she was probably still in the North Atlantic and might try to reach home through the screen of the Northern Patrol. In fact, Deutschland was already back in Germany, and Kennedy was about to meet something much worse. At first, Kennedy thought a strange ship crossing his bow was a blockade runner and ordered that a boarding party be mustered and stand by. It was just before 4 pm on this miserable evening and already very dark. A cold, brilliant moon shimmered above the heaving white wave crests of a black and greedy sea.

It did not take the British commander long to identify the stranger as a German warship, and a big one. At first he could see only one warship, and he concluded that his opponent was probably Deutschland, a smaller ship than either Scharnhorst or Gneisenau. Even at that, Kennedy knew he was hopelessly outgunned, facing a powerful warship he could not hope to damage with his own puny armament. The situation was even worse than he knew, for in fact he was faced with not one but two even bigger enemy ships, both more powerful than the pocket battleship.

“Stop or We Sink You”

Captain Kennedy knew that his ancient 5.9s were no match for an armored ship bearing 11-inch, radar-directed guns. To buy time, Kennedy signaled to Scharnhorst that he would heave to, and at the same time he went to full ahead, pushing Rawalpindi past her maximum speed. At the same time, he radioed that he had encountered Deutschland, alerting the Admiralty and the other ships of the picket line that at least one big German surface unit was at sea.

For a little while, he could shelter inside intermittent rain squalls, but they could not hide his ship for long. And now he spotted another warship looming up out of the night and radioed that he had also sighted either heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper or light cruiser Emden. He was wrong, of course. The newcomer was Gneisenau, but the identity of her killers did not matter much to Rawalpindi. She was finished in either case, and now all that remained to Captain Kennedy was to decide how this encounter would end. He had no good alternatives.

Now Scharnhorst signaled again, “Stop or we sink you,” and at last fired a round across Rawalpindi’s bow. Kennedy knew he could bluff no longer, but he kept on steaming away in an effort to save his ship, driving hard to the east, trying to lay a smoke screen with chemical floats dropped overboard. These did not function, and his ship was deprived of even this minimal protection.

Abandoning Ship

Kennedy knew that Deutschland could easily run down Rawalpindi and crush the thin-flanked liner with her big guns. The same was of course true of Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, both of which could make 29 knots. The auxiliary cruiser had even less hope of hurting her huge opponents with her own obsolescent weapons, popguns in comparison to the battlecruisers’ heavy artillery.

And so Captain Kennedy was faced with a dismal choice: keep running and delay the inevitable, or turn and go down fighting. Being Royal Navy, that was no choice at all. And so he turned Rawalpindi back into the teeth of the big German guns, charging down on his huge opponents. A salvo from Scharnhorst’s guns roared in, close but falling short. Rawalpindi answered, and her gunnery was good. Shells ripped the water close to Scharnhorst, and one of Rawalpindi’s old guns got a shell into the battlecruiser, hitting her quarterdeck and causing some casualties.

Rawalpindi sheltered briefly in a rain squall, but as she steamed into the open again, she was hammered by salvo after salvo. When a big shell destroyed her generators she lost all electric power, including power to her shell hoists, so that her gun crews were reduced to manhandling shells up from the magazines to feed the old guns. On decks littered with dead and wounded shipmates they keep shooting. And now, within 10 minutes of the start of the engagement, Gneisenau entered the fray, swinging around to Rawalpindi’s unengaged flank and pounding the suffering vessel from her other side. Now Kennedy’s gunners had to divide their fire between the two big ships, and gun after gun fell silent on Rawalpindi as the crews died at their posts.

Early in the engagement a salvo from Scharnhorst tore into the superstructure of the British ship, causing massive damage and starting an enormous fire that lit up the night like some sort of maleficent torch. A German shell smashed into Rawalpindi’s bridge, and her radio, still sending a warning of the German raiders, fell silent for good. The same shell probably killed Captain Kennedy, his quartermaster, and everybody else on the bridge. At last, in the blazing chaos a single British gun kept on firing, only two men of her crew still standing, and the story goes that other sailors vainly fired on the German ships with machine guns and even rifles. By 12 minutes past four the liner lay dead in the water, a huge blazing pyre, her last gun out of action, only a hulk but still afloat. The German ships kept on shelling her for another 10 minutes and then ceased fire.

Rawalpindi’s crewmen, those who were still alive, began to abandon ship, but only three boats remained intact after the pounding the ship had taken. The crew loaded wounded men into the surviving boats as Rawalpindi shook and trembled from internal explosions. Even one of the three boats was holed, and some men dove into the icy sea. At these latitudes, a man in the water did not last long.

“Please Send Boats”

From Rawalpindi’s blazing superstructure somebody—a hero never identified—sent a message in Morse Code to the Germans, repeating over and over: “please send boats.” And in the best tradition of the sea, Admiral Marschall gave the order to rescue survivors from the wild seas. Just launching boats in this chaos of squalls and gale and crashing seas was desperate work, but Scharnhorst managed to pluck a few British survivors from the sea. To their enormous credit, the German ships stayed for an hour or more, doing everything in their power to save a few more seamen. Marschall knew Rawalpindi almost surely got a radio message out, bringing other British warships charging to the rescue, but still he stayed.

And then, a little after 7 pm, a German lookout spotted a warship in the gloom—she had to be British—and Marschall reluctantly broke off rescue operations just as a boatload of survivors was about to be lifted from the sea. Nobody, then or after, would blame Marschall. His first responsibility was to safeguard his own ships and crews, and he could not wait motionless in the presence of an enemy vessel. It was the luck of the sea, and it affected both sides. When the Royal Navy sank the battleship Bismarck in May 1941, British rescue operations had to be broken off with survivors still in the water because a U-boat was reported in the area.

As the German battlecruisers moved away, they were shadowed by the newcomer, the British light cruiser Newcastle. She had been Rawalpindi’s nearest neighbor in the Northern Patrol’s screen and had sailed for the scene of the fight as soon as she had gotten Rawalpindi’s report that she had sighted a German warship. She had spotted the blazing furnace that was Rawalpindi and homed in on the flames. Although she packed 12 six-inch guns, Newcastle could not hope to fight either of the big German ships, let alone both.

She could shadow the Germans, however, for she was nimble and she could do 32 knots, fast enough to run from Scharnhorst and Gneisenau if either of them turned on her. She was not equipped with radar, however, and she lost the two battlecruisers in the gloom as the rain turned into a swirling white wall of snow that cut visibility to about 1,200 feet. Once the snow cleared a little, Newcastle tried in vain to regain contact, then turned back to the site of the battle in time to see the flaming hulk of Rawalpindi turn turtle and go down. The cruiser found the boatload of men that Marschall had to abandon and miraculously fished from the sea two half-frozen crewmen still clinging grimly to an overturned boat. There were no more.

Captain Kennedy, 41 officers, and 226 men had died with their ship.

An Exposed British Convoy

HMS Jervis Bay was also a liner by trade, constructed by Vickers at Barrow in Furness in 1922. She was one of five such ships originally built for the Australian Commonwealth Line, and she and her sisters plied a monthly schedule between London and Brisbane. In the mid-30s, she became part of the new Aberdeen & Commonwealth Line, serving the same route. She and her sisters, all named for bays, could do 15 knots.

And so it went through the last years of peace until, when the specter of war loomed over Europe in August 1939, she was requisitioned by the Admiralty and converted into an armed merchant cruiser. Since everything, including weapons, was in short supply, all the yards could give her were seven 6-inch guns manufactured prior to World War I. She had no ranging equipment worthy of the name, and no armor at all. But she did get a coat of gray paint, a white ensign, a 255-man crew, and a captain with a heart of oak, Captain S.E. Fogarty Fegen, Royal Navy.

On November 5, 1940, about halfway between Ireland and Newfoundland, Jervis Bay was shepherding convoy HGX84, 37 merchantmen bound eastward for Britain. Jervis Bay was the only escort. In mid-afternoon, as the long North Atlantic night was already coming down, the liner sighted a huge shape on the skyline, a capital ship obviously, but at that range the lookouts could not make out the newcomer’s nationality. Fegen signaled the stranger, asking “what ship?” over and over, but he got no answer. At last the captain had to conclude that the big stranger was an enemy. And he knew where his duty lay.

The strange, silent warship was the pocket battleship Admiral Scheer, which had slipped into the Atlantic through the Denmark Strait in the last days of October. The German Navy’s B-Dienst (Funkbeobachdungsdienst or radio observation service) had intercepted British signals and advised the Kriegsmarine command that a large British convoy had left Halifax, Nova Scotia, on October 27. Admiral Scheer put to sea to attack the convoy, and on November 5, her Arado floatplane located HGX84 and reported that there was no sign of an escort. The British ships should be cold meat.

HMS Jervis Bay and Scheer Converge

Scheer was a powerful ship, the ideal commerce raider, one of the Deutschland-class warships launched in the 1930s; she was sister to Admiral Graf Spee and Deutschland (renamed Lützow to avoid national embarrassment if she were lost in battle). After an undistinguished career, Lützow would go down under British bombs at Scheinemuende in 1945. And it would not be long, mid-December 1939, before Graf Spee would be gone forever, scuttled in the estuary of the River Plate after she was engaged in the South Atlantic by Royal Navy cruisers and driven to sanctuary in Uruguay.

But all of that was in the future, and now Scheer was loose, sailing toward the convoy lanes looking for prey. She was a mighty hunter with an enormous range, something around 20,000 nautical miles depending on her speed. She was fast, too, designed with the speed to run away from any ship she did not outgun. She was new, launched in 1934, and she and her sisters were the first ships of this size to have welded hulls and diesel engines. Her diesels could give her 28 knots at need, some 10 knots faster than Jervis Bay.

Admiral Scheer’s ship’s company numbered more than 900, and her formidable main armament was six 11-inch Krupp guns in two turrets. These tubes were a new model, which could hurl a 670-pound shell some 30,000 yards. She also packed 14 5.9-inch guns, torpedo tubes, and a gaggle of antiaircraft weaponry as well. Her armor was heavy over her vital parts—some five inches over the front of her turrets and on her conning tower.

As Scheer bore down on convoy HGX84, Jervis Bay turned to meet her, swinging in to close with the raider at her best speed. Standing on his bridge watching the big German, Captain Fegen again signaled “what ship?” There was still no answer, as Scheer’s commander, Kapitaen-zur-See Theodor Kranke drove his big ship ever closer, intent on bringing Jervis Bay well within the range of his heavy guns before confirming that Scheer was hostile.

Captain Fegen had no notice that a German raider was loose in the Atlantic, and at first he naturally assumed that the newcomer was friendly. His suspicions grew as Scheer bore down on the convoy without answering his signals. And then, about 5:30 on this dreary night, Scheer turned broadside to Jervis Bay, opening the arc of fire for both her turrets, and the muzzle flashes of her main guns flickered in the gathering darkness. Now captain Fegen must have known that time was running out for him, his crew and his ship. His ship could not match speed with the attacker, which could stay outside the range of his antique guns and pound Jervis Bay to junk without risk to itself. Even if he could close with Scheer, he could not hurt her much with his venerable six-inch weapons.

Captain Fegen’s Brave Sacrifice

Captain Fegen ordered the firing of red flares, warning the ships of the convoy to scatter. As the merchantmen fled in all directions, Fegen sent Jervis Bay straight at the battleship, her four little forward guns banging away, dropping smoke floats as she tried to close with her enemy. The raider was then about eight miles away, well out of range of Fegen’s old guns, but Jervis Bay kept shooting, trying to keep the German as far as possible from the helpless convoy.

Speer’s big 11-inch main guns quickly began to hit Jervis Bay, knocking out her fire direction center and finally sending a shell howling into the bridge. The explosion killed nearly everyone on the bridge; it tore off one of Fegen’s arms, but he stayed grimly in command, keeping his ship headed for Scheer. With his bridge destroyed and everybody on it killed or wounded, in spite of his hideous injury Fegen made his way aft through the flaming wreckage of his dying ship. There he remained in command in the secondary steering position until a second shell killed him.

With her central fire direction destroyed, Jervis Bay’s surviving guns kept on shooting independently, their shells still falling short as the battered liner vainly tried to close the range and damage her huge enemy. Shell after enormous shell tore at Jervis Bay until at last she lay dead in the water, her decks and bulkheads splashed with the blood of her crew. Finally, her last gun fell silent and she began to founder, but she had bought the ships of the convoy a chance to get away; she had held up the German raider long enough for the convoy’s plodding merchantmen to scatter into the night.

Her life finished, she turned on her side and then began her slide to the bottom bow first, taking with her 190 of her crew of more than 250. With enormous daring, Swedish Captain Sven Olander waited until Scheer had passed by in the darkness in pursuit of the other ships, then turned his freighter, Stureholm, back to recover such survivors of Jervis Bay as he could find. There were only 65. A few more were picked up over the next few days.

By now the merchantmen had scattered to the four winds, hurrying at top speed toward every point of the compass, and the gloom of arctic night was coming swiftly down to cover their escape. Thanks to Fegen’s gritty charge, by the time Scheer could turn her attention to her primary targets, the merchantmen of the convoy, she could only catch and sink five ships. Thirty-two got away in the darkness to reach Britain with their vital cargoes. Jervis Bay was gone, but she had died well, and the courage of her crew was reflected in the posthumous award of the Victoria Cross to Captain Fegen. The citation told it all: “Captain Fegen immediately engaged the enemy head-on, thus giving the ships of the convoy time to scatter. Out-gunned and on fire Jervis Bay maintained the unequal fight for three hours, although the captain’s right arm was shattered and his bridge was shot from under him. He went down with his ship but it was due to him that 31 ships of the convoy escaped.”

HGX84 Escapes

There is a little-known postscript to the gallantry of Fegen and his crew, played out in the cold and fog and darkness not far from Jervis Bay’s grave. Beaverford, a merchantman owned by the Canadian Pacific Railways, was part of Convoy HGX84 and scattered with the rest. She was a 10,000-ton, Glasgow-built freighter capable of 15 knots, requisitioned for war service early in 1940 and fitted with a couple of little 4-inch guns. In the falling darkness Captain E. Pettigrew watched the big German warship bearing down on Beaverford and decided he would not go softly into that dark night. Pettigrew swung his ship through 180 degrees and went straight for the raider, a little like a mouse charging a mastiff, banging away with his forward 4-incher.

In the gathering gloom Captain Kranke of Scheer could not be certain what sort of ship was shooting at him. Understandably cautious, he stood off and hammered Beaverford with his big guns. In the arctic darkness the stubborn freighter occupied her huge opponent until about an hour before midnight. Then she blew up, a monstrous fireball in the gloom of the northern night. Only wreckage remained in the icy water, and of her 77-man crew, there were no survivors.

All in all, Scheer’s attack on HGX84 was a great disappointment to the Kriegsmarine. Thanks to the fierce resistance of Jervis Bay and Beaverford, most of the convoy’s ships won their way clear to sail to safety in Great Britain. Besides Jervis Bay and Beaverford, the pocket battleship had managed to sink merchantmen Fresno City, Maidan, Trewellard, Kenbane Head, and Mopan, a lonely little banana boat Scheer had sunk on her way to attack the convoy. Tanker San Demetrio, set ablaze by the battleship’s guns and abandoned by her crew, stubbornly refused to sink, and at last her men rowed back to her, reboarded her, attacked and beat down the flames, and brought her limping to port in England.

The Fate of the Kriegsmarine Surface Fleet

In the end, the killers of Rawalpindi and Jervis Bay became victims themselves. On the day after Christmas 1943, shells from the battleship HMS Duke of York and British cruisers mortally wounded Scharnhorst in the arctic darkness above North Cape. She was finally sent to the bottom by the torpedoes of cruisers Belfast and Jamaica and accompanying Royal Navy destroyers. Of her crew, 1,800 died with her.

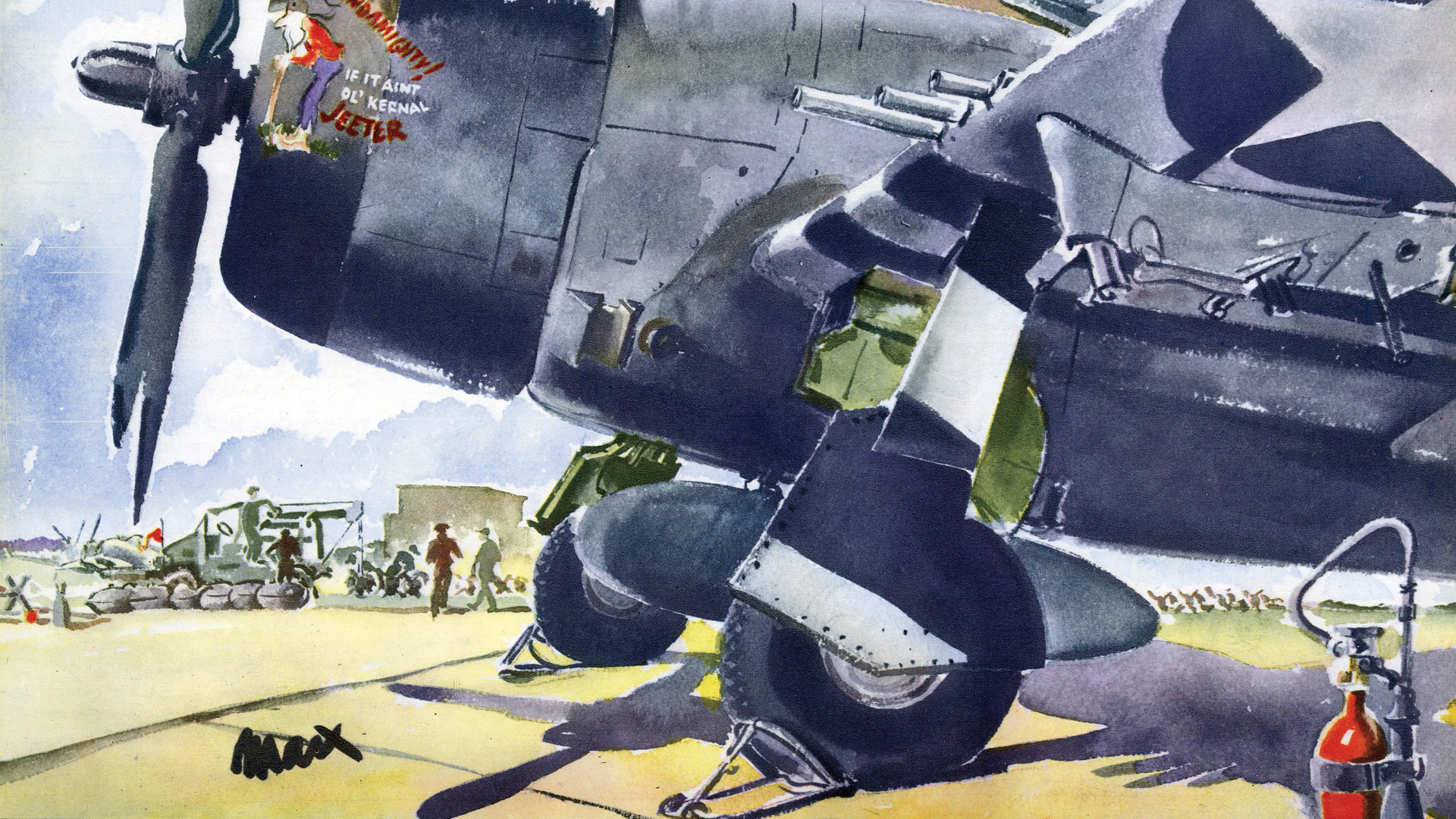

Her sister ship, Gneisenau, was out of action for most of a year from a British submarine’s torpedo during the 1940 Norwegian invasion. And then, while she was docked for repairs at Brest, in the gray dawn of April 6, 1941, a single Bristol Beaufort torpedo bomber bore in through a hail of flak to put a torpedo into her stern. Antiaircraft fire tore the Beaufort and her gutsy crew to pieces, but it was the beginning of the end for big Gneisenau. Five nights later British bombers hit her four times, doing more damage. Repaired, she was damaged by a British mine in early 1942, and she was never again operational. In March 1945, she was scuttled by the Germans after a British bomb had touched off an enormous fire in her vitals.

Scheer, transferred to the Baltic, had no more substantial successes, save for a remarkable foray deep into Russian waters. In the latter days of the war she fired missions in support of German ground forces falling back along the rim of the Baltic. And then, in April 1945, she took five British bombs and capsized while docked at Kiel, probably pitched over by the sheer force of the big bombs landing beside her. There she remained, lying on her side, literally part of the harbor. She was later covered with earth and rubble, and an industrial area was constructed over her grave.

The armed merchant cruisers were never considered anything but a stopgap, a temporary expedient to remedy the crucial lack of escort vessels for the all-important convoys. All the merchant cruisers were withdrawn from service well before the end of the war. But while they were needed they did their job in the best traditions of the Royal Navy, even to the final sacrifice. They should not be forgotten.

Join The Conversation

Comments