By Herb Kugel

Special Sea Attack Force (SSAF) was an ordinary-sounding name for the pitifully tiny remnant of what was once the mighty Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). However, the word “Special” in the Japanese military possessed a unique and dark meaning. In late 1944, when Japan’s defeat became obvious, the desperate Japanese began encouraging kamikaze, or suicide aircraft missions, and created “special” units for carrying out these missions. Thus, “special” became a nonthreatening word for “suicidal,” and Special Sea Attack Force became the euphemistic name for a Suicide Sea Attack Force. The SSAF comprised just 10 ships. The first and foremost of these was the mighty battleship Yamato, the world’s largest dreadnought and pride of the IJN. She was to be escorted to her glorious death by the light cruiser Yahagi and eight destroyers: Asashimo, Fuyutsuki, Hamakaze, Hatsushimo, Isokaze, Kasumi, Suzutsuki, and Yukikaze, which were also scheduled to be sacrificed in a final attempt to cripple the American fleet.

The “Super Battleship” Yamato Class: Why Only Two Were Built

The design and construction of these battleships began in October 1934––well before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, although the Japanese Naval General Staff was even then planning for the inevitable showdown with the United States. Thus they ordered their Navy Technical Department (Kampon) to report on the feasibility of building a new generation of battleships that were superior to anything America had manufactured up to that time. The Japanese realized they could not match American quantity; the Americans could produce far more battleships than Japan ever might, but the Japanese designers felt certain they could build more powerful battleships than the Americans could.

The Japanese government expressed little doubt that these “super battleships” could be designed and built, and so, on December 29, 1934, it gave the required two years’ notice that, after December 31, 1936, Japan would no longer be a party to either the 1922 Washington and 1930 London naval treaties. Both agreements contained restrictions on Japanese naval armaments, something Japan now totally rejected. As of January 1, 1937, Japan unilaterally declared it would no longer be bound by these treaties or any restrictions whatsoever to its powerfully expanding military.

After the final construction plans for the three ships were approved in March 1937, they were quickly ordered into production under the Third Fleet Replenishment Program. Following tradition, each ship was named after a prefecture of old Japan. Not merely muscle-flexing or saber-rattling, Japan invaded China on July 7, 1937.

The battleship Yamato was the first of what were to have been five Yamato-class battleships, but only three were built. The Yamato was commissioned on December 16, 1941, and the second Yamato-class ship, the Musashi, was commissioned on August 5, 1942. A third Yamato-class battleship, the Shinano, was in the works, but she was hurriedly converted into an aircraft carrier while still under construction, this conversion being made to help make up for the Japanese carrier losses at the Battle of Midway in early June 1942. The carrier Shinano was formally commissioned on November 19, 1944, but just 10 days later, on the second day of her maiden cruise, she was torpedoed and sunk by the American submarine Archer-Fish (SS-311).

The Yamato-class battleship characteristics, according to their final production plan, placed their overall length at 862.83 feet and their fully loaded displacement at 72,800 long tons (73,968 metric tons, 81,536 short tons). They had a top speed of 27 knots. (By comparison, the new American Iowa-class battleships were 887 feet long, but displaced only 45,000 tons and had a top speed of 33 knots.)

Naoyoshi Ishida, an officer who served aboard the Yamato, recalled that when he first saw her, his initial thought was, “How huge it is! When you walk inside, there are arrows telling you which direction is the front and which is the back—otherwise you can’t tell. For a couple of days I didn’t even know how to get back to my own quarters. Everyone was like that…. I knew it was a very capable battleship. The guns were enormous. Back then, I really wanted to engage in battle with an American battleship in the Pacific.”

Both the battleship Yamato and the Musashi were heavily armed and armored, and the Japanese firmly believed these battleships were unmatchable and unsinkable.

What were certainly unmatchable were the nine 18.1-inch (460mm) guns both battleships carried, as opposed to the nine 16-inch (406mm) guns on America’s top warships, the Iowa-class battleships. The Yamato’s armor-piercing 18.1-inch shells weighed 3,200 pounds each and could be hurled more than 25 miles at 40-second intervals. No Western battleship ever matched this.

A Reluctance to Use the Yamato and Musashi

But the Japanese encountered difficulties with the Yamato and the Musashi soon after they were completed. Because of their weight, the two battleships consumed huge quantities of fuel oil, a product Japan did not have in great supply. Another consideration was the fact that the battleships were not only devastating weapons, they were also powerful symbols of national pride, and their loss would be a decimating blow to national as well as to naval morale. Thus, the battleships were to be used in battle cautiously, and not until late in the war, when the Japanese Naval General Staff saw the shadows of defeat darkening around them.

Various reasons for not using the Yamato were put forth, but Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the commander in chief of the Combined Fleet, the main oceangoing component of the IJN, displayed a reluctance to commit the Yamato, his flagship, to battle. Even after Yamamoto died when his plane was shot down by U.S. Army Air Force P-38 Lightning fighters on April 18, 1943, his successors did not involve either the Yamato or the Musashi in any significant combat until the closing months of the war.

The battleship Yamato was given the name “Hotel Yamato” by the Japanese Pacific Ocean cruiser and destroyer crews. The battleship spent only a single day away from her Japanese Truk Island naval base in the Caroline Islands during the period between her arrival on August 29, 1942, and her departure on May 8, 1943. Nor did she take part in the critical Solomon Islands Campaign, which began on August 7, 1942, and lasted through February 1943.

While on patrol in December 1943, the Yamato was damaged by a torpedo launched from the USS Skate (SS-305), which struck fear in the hearts of the IJN admirals, who did not want to lose her. She finally saw action during later stages of the war, participating in actions in the Philippine Sea and then as the command ship of Admiral Takeo Kurita, when she devastated a small American fleet off Samar.

“The Most Tragic and Heroic Act of the War”

By early October 1944, the Americans had “island-hopped” their way across the Pacific and were preparing to invade the Philippine Islands. The Japanese naval defense plan was code-named named Sho-I-Go (“Victory”), and its objective was simple: Sink the American invasion fleet, maintain the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, and, by doing this, protect Japan from invasion.

To accomplish this goal, the Japanese committed virtually everything that was left of the IJN in a desperate effort to destroy the American invasion force. However, they were committing what remained of a navy that had no air support left. Significantly, both the Yamato and the Musashi were committed to stop America at what became known as the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

On October 24, 1944, the Musashi was sunk during this battle by 17 bomb strikes and 19 torpedo strikes; 1,023 of the Musashi’s crew of 2,399 perished, while the Americans lost 18 planes. The Yamato suffered relatively little significant damage during the battle and slipped away.

The Japanese were beaten at Leyte Gulf and the Americans pushed closer to the Central Japanese Home Islands by invading Okinawa in Operation Iceberg on April 1, 1945. Okinawa was in the Ryukyu Islands which, despite Chinese objections, had been incorporated into the Japanese empire in 1879. Because of this incorporation, the Japanese considered Okinawa a part of their homeland and would do everything to defend it.

The Japanese grew desperate as the American invasion of Okinawa was under way. The American success forced the Japanese to resort to the full deployment of their powerful last-gasp countermeasure, the “Special Forces”—the suicidal kamikaze, and, for the first time, this included the Navy. Japanese Combined Fleet commander in chief, Admiral Soemu Toyoda, overrode strong objections from members of his Naval General Staff concerning the naval usage of suicidal “special forces.” On April 3, 1945, he informed the men of his just-formed Special (Suicidal) Sea Attack Force that “the fate of our Empire depends upon this one action. I order the Special Sea Attack Force to carry out on Okinawa the most tragic and heroic act of the war.”

Admiral Toyoda’s “most tragic and heroic act of the war” involved ordering all of the SSAF’s sailors to embark on a mission to fight “to the last man.” On April 5, 1945, the SSAF staff received the following order: “The Surface Special Attack Unit is ordered to proceed via Bungo Suido Channel at dawn on Y-1 Day to reach the prescribed holding position for a high-speed run-in to the area west of Okinawa at dawn on Y-Day. Your mission is to attack the enemy fleet and supply train and destroy them. Y-Day is April 8th.”

Shizuo Kunimoto, a lieutenant junior grade on the Yamato, reported: “The special order sending the Yamato to Okinawa was written with large letters on white paper and posted on the port side of the first deck. After the Yamato set sail, all hands not on duty (about 2,000 men) were assembled on the forecastle to hear their specific orders read by the ship’s Executive Officer.”

The Yamato sailors bravely continued to honor their traditions after hearing their collective death warrant. Kunimoto commanded his men to bow toward the Imperial Palace and then toward their homes. He then led them in singing patriotic military songs for about 10 minutes, but patriotism and courage didn’t change what most of the Yamato’s sailors realized would happen to them.

On April 6, 1945 (Y-2 Day for the SSAF), waves of Japanese planes dove in suicidal attacks into Allied Pacific Fleet ships as part of Operation Kikusui (“Floating Chrysanthemums”), so named after the chrysanthemum crest of Kusunoki Masashige, a 14th-century samurai hero. Kusunoki, in what became remembered as an ultimate act of samurai fidelity, accepted a fatal and foolish command from his emperor and obediently and knowingly led his army and himself to death while fighting to carry out this absurd command. Absolute devotion to their emperor, who was considered a deity before and during World War II, was one of the foundations of kamikaze.

First Japanese pilots and now the sailors of the SSAF, allegedly all volunteers, were ordered to end their lives in the same heroic manner as Kusunoki Masashige. The IJN named their mission Ten Ichi-Go (“Heaven Number One”), and the orders to the SSAF were grimly simple: The SSAF was to sail directly into the American ships and transports supporting the Okinawa landing and inflict as much punishment on them as possible.

After this, the Yamato would be beached and use its 18.1-inch main batteries and other weapons as support for Okinawa’s land defense forces. “Surplus” Yamato crew members (that is, all nongunners) would then leave the beached Yamato and die on land while fighting together with soldiers of Okinawa’s defense garrison. The sailors on the escort ships would also die fighting. Absolutely no one was to return alive.

Nevertheless, while the Japanese Naval General Staff instructed that each ship be given only enough fuel for a one-way trip to Okinawa, harbor officials risked execution by disobeying this order and refueling the entire SSAF to capacity, giving them more than enough oil to return home if they somehow survived.

The Men of the Suicide Mission

There were three admirals in the SSAF, two of whom were aboard the Yamato. While Admiral Kosaku Ariga captained the Yamato, Vice Admiral Seiichi Ito commanded the entire SSAF. The Yahagi and the eight escort destroyers that constituted the Second Destroyer Squadron were commanded by Rear Admiral KeizoōKomura, whose headquarters were on the Yahagi. Seiichi Itoōhad furiously opposed the mission, but ultimate control rested with Admiral Soemu Toyoda, who was stationed near Tokyo.

Seiichi Ito’s main reason for objecting was the complete lack of air protection, something not the case for the kamikaze pilots as they flew into their April 6 death dives. Ito’s other reasons for opposing the mission were his concern about the terrible numerical inferiority of his force—eight destroyers compared to America’s 60 destroyers. He also objected to the time of sailing. He wanted the time arranged to allow the SSAF to arrive and attack at night. Ito reportedly gnashed his teeth in rage when his argument that the time of departure should be left to the mission commander was rejected.

Instead of being elated at the prospect of being chosen to die gloriously for the emperor, the Yamato’s crew was miserable and despondent on the night of April 5, 1945 (Y-3 Day), the night before the SSAF departed on its final mission. At 5:30 pm, three orders were broadcast over the ship’s public address system:

“All cadets prepare to leave the ship.”

“Distribute sake to all divisions.”

“Open the ship’s store.”

Sixty-seven naval cadets of Etajima Naval Academy Class No. 74, who had arrived three days earlier, were ordered to go ashore. But first, the cadets were summoned to the First Wardroom, a room normally reserved for the Yamato’s ensigns and junior grade lieutenants. Sake was drunk in ceremonial farewell. The cadets begged to remain but were gently yet firmly ordered to leave by the Yamato’s executive officer, Jiro Nomura. “We couldn’t bear to take them along on an expedition into certain death,” Nomura said. That night many sailors sang unhappy folk songs and drank heavily.

The next morning, April 6, a dozen or so seriously ill sailors were transferred and some 20 sailors were reassigned at the last moment. Their eyes filled with both regret and relief when they heard the news. In addition, there was the matter of the older sailors, those over age 40, who had proven to be ineffective in what little combat the Yamato had already seen; their deaths for no reason would be a brutal blow to their families. After consultation, Admiral Ariga permitted some of these men to leave the ship.

A Black Omen: Sinking of the Asashimo

The SSAF set sail that day, the ships leaving Tokuyama at 4:00 pm. The Yahagi led the SSAF, followed by the eight destroyers, with the Yamato bringing up the rear. On the same day, 355 kamikaze planes attacked the Allied Pacific Fleet in the largest kamikaze attack of the war, while the SSAF, as planned, sailed without any air protection whatsoever.

The nine escort vessels were manned by first-rate crews, combat veterans of many battles. However, their little fleet had absolutely no chance to successfully protect the Yamato on her final voyage.

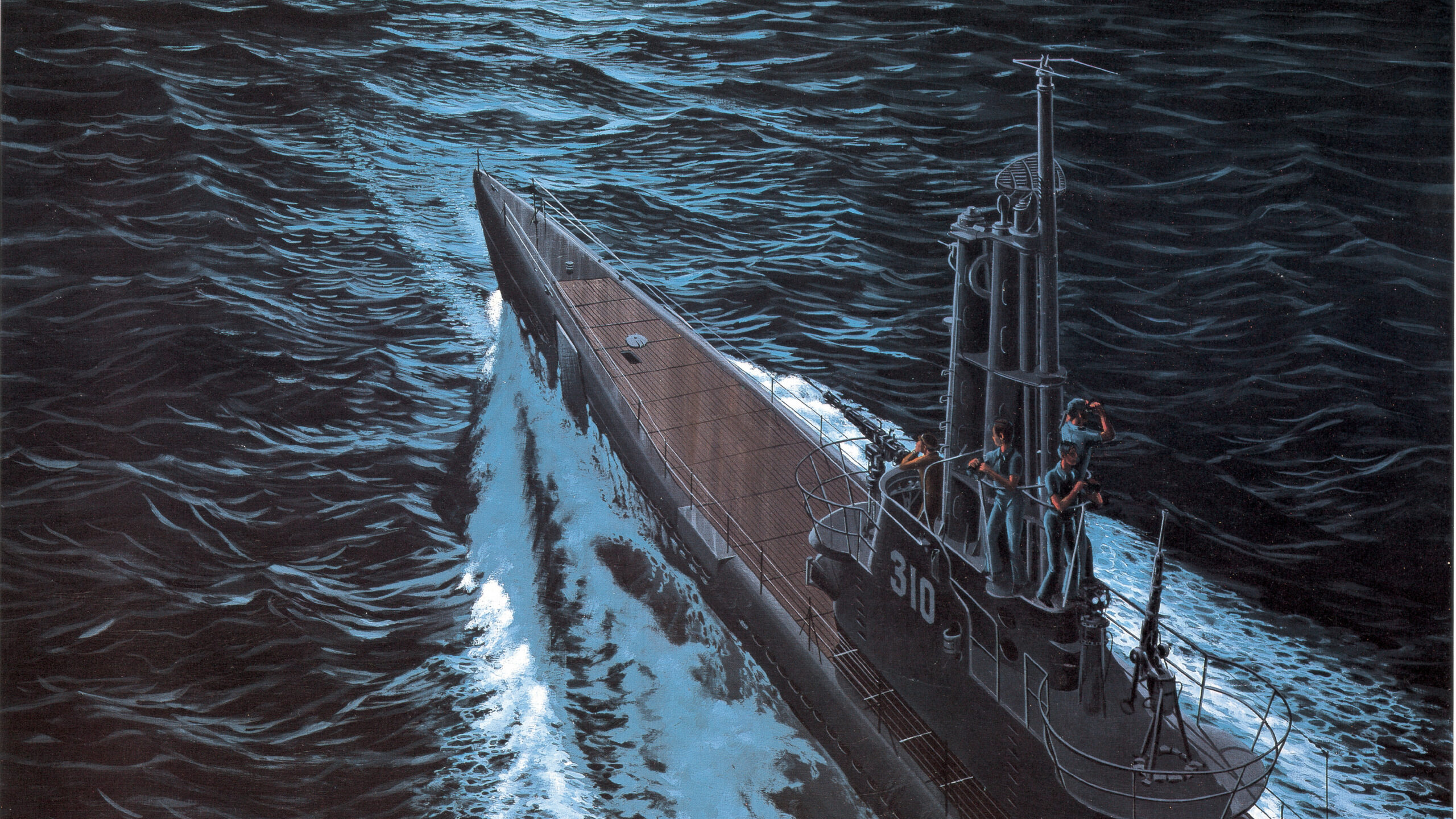

The Americans were alerted by the submarine Threadfin (SS-410), which was on patrol near Fukashima, a tiny island at the mouth of the Bungo Strait. At 9:00 pm on Y-2, the Threadfin radioed the SSAF’s location to ComSubPac (Commander, Submarine Forces, Pacific) at Guam. Later, the submarine Hackleback (SS-295) sighted the Yamato and reported the SSAF’s location. The American submarines openly communicated with each other via radio in unencrypted English, with the radio operators frequently mentioning the Yamato by name. According to U.S. Navy records that Japanese researchers obtained after the war, the two submarines were ordered to track and report the movements of the Japanese ships but not to attack unless given permission.

What the Americans could not know was that Radio Officer Ensign Shigeo Yamada on the Yahagi was a Nisei, the son of Japanese immigrants to the United States. Born and educated in America, Yamada translated and reported to his senior officers what he overheard the Americans saying. Yamada, who was born in Idaho and claimed to have been “raised on potatoes,” reported that the American radio operators often referred to the Yamato as “King Battleship.” He, like fellow Nisei Kunio Nakatani, had been sent to university in Japan by their families and were trapped when the war started. These and other Nisei students could face either the draft, or imprisonment for collaboration, or even possible execution for espionage. Enlisting in the IJN often seemed the best choice for these young American citizens.

(Shigeo Yamada would survive the sinking of the cruiser Yahagi. After the war, his American citizenship was revoked, but he was later allowed to return to the United States, where he worked for Japan Air Lines (JAL) and eventually returned to Japan as a JAL vice president.)

Shortly before 7:00 am on April 7 (Y-1 Day), the Asashimo hoisted the signal “engine casualty” and began to fall behind the SSAF armada. Some sailors on the Yahagi called this a black omen for the entire unit as the Asashimo fell farther and farther behind the rest of the SSAF. Takekuni Ikeda, who was serving as an ensign aboard the Yahagi, recalled in his 2007 memoir The Imperial Navy’s Final Sortie, “But … [the Asashimo] continued to fall behind and gradually disappeared in the mist. I clearly remember that the bridge of the Yahagi was in total silence. The day of destiny began under such circumstance.”

As the morning progressed, the Yamato’s radar detected more and more American planes hovering above them. At 10 minutes past noon, the Asashimo radioed that she was engaging enemy planes; then her radio abruptly went silent. The Asashimo had been sunk; her entire crew, 326 men, died when she went down.

First Strike on the Battleship Yamato

While the Americans’ initial attacks inflicted a heavy toll, their main attacks were yet to come. On the other SSAF ships, experienced Japanese lookouts recognized the increasing number of U.S. Navy Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters, Chance-Vought F4U Corsair fighters, Curtiss SB2C Helldiver dive-bombers, and Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers circling above them.

Initially, Fifth Fleet commander Admiral Raymond Spruance ordered six of his battleships that were engaged in shore bombardment at the Okinawa beaches to prepare to attack the battleship Yamato. However, Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher, commander of the powerful Carrier Task Force 58, pushed Spruance to change his orders and replace the six battleships with air strikes from Task Force 58 planes. Mitscher had been determined to attack the Yamato and had ignored Spruance’s order to avoid the battleship. At about 10:00 am on Y-1 day, Mitscher had ordered up flights of 280 and 106 planes, respectively, and requested permission from Spruance to attack the Yamato and her escorts only after his planes were airborne. Spruance’s reply was curt: “You take them.”

The SSAF crews had been at general quarters from dawn on Y-1 Day. At 7:00 am there had been a ceremonial breakfast after which all doors, hatches, and ventilators were closed tightly as the ships readied for battle. At about 8:45, the SSAF was sighted as seven Grumman F6F Hellcat scout planes flew over them. The Hellcats circled the force but kept their distance and made no effort to attack. At 10:14, the Japanese detected two Martin Mariner PBM seaplanes, and the Yamato fired a salvo at them from her 18.1-inch guns but missed. The Japanese also spotted the submarine Hackleback trailing them. Three minutes later, the Yamato received a report from a scout plane that Task Force 58 had been located east of Okinawa, 250 nautical miles (288 statute miles) from the SSAF.

Within Task Force 58, at around 10:00 am on Y-1 Day, the first full strike of Mitscher’s aircraft—280 fighters, dive-bombers, and torpedo planes—readied to attack the SSAF. Tension was high among the American pilots; they knew they had only one primary target: the Yamato.

Aboard the Yamato, a messenger boy, his face all smiles and showing no awareness of the anguish of the older men, happily informed everyone that the crew would be served bean soup and dumplings for dinner.

At 10:38, the carrier Yorktown (CV-10) launched 43 planes, taking off more than half an hour later than the other groups. At about 12:34, the Yamato’s lookouts detected American planes off the battleship’s port bow at 40,000 yards (23 miles). The Yamato commenced firing, and at 12:41 the SSAF increased its speed to nearly 28 knots (32 mph), matching the Yamato’s maximum speed. The nine 18.1-inch guns fired Sanshikidan “beehive” shells––projectiles that functioned like shotgun shells, scattering thousands of pellets or bits of shrapnel into the air when they exploded. Although these shells were especially designed to be fired from ships against attacking aircraft, the American planes flew straight through the shrapnel the shells generated.

The Yamato’s main guns were joined in firing by six 6.1-inch guns, 24 5-inch antiaircraft guns, 150 25mm (0.98 inch) antiaircraft guns, and four 13mm (0.51-inch) machine guns, but this firing failed to produce any significant American losses; the gunners quickly learned that their curtain of anti-aircraft fire was far less effective than they had assumed it would be.

The Japanese anti-aircraft gunners, suffering casualties and communications damage, could not maintain coordinated fire against the zigzagging American planes. Fear was a powerful factor. Harvey Ewing, a rear seat gunner in an attacking Avenger, reported: “I could see bursts of anti-aircraft fire all around the plane as I made the run. To say that I was scared would be an understatement. We dropped the fish [torpedoes] and pulled up on one wing over the Yamato and seemed to hang there for minutes as the ship was firing every gun, including its 18-inch rifles, at the planes following us in.”

At about 12:40, the battleship Yamato was hit by two bombs, both landing near the aft secondary gun turret, and three minutes later her port bow was struck by a torpedo. The bombs inflicted casualties; they knocked out the aft secondary battery fire control unit and caused other serious damage. The exploding torpedo killed sailors and also allowed about 2,350 tons of water to pour into the Yamato. The damage-control unit contained the damage by counterflooding with about 604 tons of water. (Counterflooding is flooding an “opposing” section of a listing ship in an effort to balance the ship and keep it level.)

At about 12:47, the destroyer Hamakaze was sunk. A bomb hit her aft deck, sending up a column of flames, and then a torpedo blast broke her in two. Of her crew of 240 men, 100 were killed and another 45 injured. At about the same time, the Suzutsuki received a 500-pound bomb hit to starboard, on top of her No. 2 gun mount, and caught fire. Although hit again, she managed to struggle back to Japan. Of her 263-man crew, 57 were killed and 34 were wounded.

SSAF Collapses

At about 12:50, the first wave of American warplanes had completed its attack and withdrew; at approximately 1:02 pm, the second wave arrived. The second wave attack was a coordinated strike, with dive-bombers flying high overhead to begin their attacks while torpedo bombers came in from all directions, flying at just above the wave tops. This second attack lasted about a half hour, during which the Yamato was hit with at least two more bombs and no fewer than four torpedoes. The ship also took in about 3,000 tons of water and listed some seven degrees to port. Damage control corrected this dangerous list by counterflooding the starboard engine and boiler rooms. The list was temporarily corrected, but many men within the ship drowned during the flooding.

At this time, many SSAF sailors were in the water and feared there would be no efforts made to rescue them by their fellow sailors because they were all part of a suicide force. However, Admiral Seiichi Ito, realizing his suicide attack force would never reach Okinawa, aborted the mission and ordered the rescue of survivors; Admiral Toyoda accepted Ito’s decision.

Men responded differently as what they knew to be certain death approached. An officer, his face wreathed in smiles, cheerfully praised the Americans for their skill and bravery. Kunimoto, who was a damage-control officer, realized his ship was doomed as water rushed in around them. Still, he and his shipmates began giving cheers of “Long reign the emperor.”

Not all the sailors could accept the idea that their mighty Yamato could sink or that they could die. Heiji Tsuboi, who had been a petty officer 2nd class and manned the battleship’s No. 5 anti-aircraft battery, recalled: “We were told [by] our Senior Chief that we were not able to return alive from the mission.… I was busy operating my anti-aircraft gun all through the battle until the ship’s last minutes. I remember well that I felt a somewhat heavy shock had been transmitted from the bottom of the ship. I thought it must be a torpedo attack but did not think the ship would be sunk.”

The Yamato’s sheer size made her a tempting target, and she continued to be pummeled unmercifully from above by an unceasing rain of bombs and bullets and from below by torpedoes.

Scenes of sadness and courage played out aboard the task force’s doomed ships. As the end approached, 20-year-old Ensign Yoshida Mitsuru, stationed on the Yamato’s bridge, watched in disbelief and horror as American dive-bombers sent three more torpedoes into the ship’s port side and then raked the anti-aircraft gun crews with lethal machine-gun fire. He wrote later: “That these pilots repeated their attacks with accuracy and coolness was a sheer display of the unfathomable undreamed-of strength of our foes.”

Mitsuru survived the sinking of the ship and wrote his account in Requiem for Battleship Yamato. One the most poignant incidents he relates involved an assistant communications officer, a Nisei ensign named Kunio Nakatani, who was drafted out of the classroom while attending Keio University; both of his two younger brothers were in the U.S. Army and serving in Europe. Mitsuru described Nakatani as a good-natured young man who went diligently about his work. Although Nakatani alone on the Yamato could pick up and translate American transmissions, the younger officers looked at him with contempt and constantly reviled him.

Nakatani showed Yoshida a letter he had just received from his mother in America, sent through Switzerland and received just before the Yamato sailed on her final voyage: “We are fine. Please put your best effort into your duties. And let’s both pray for peace.”

Recalling the capsizing battleship’s last moments, Yoshida attributed to the ocean an almost malevolent presence when he wrote: “Dark waves splattered and reached for us as the stricken ship heeled to an incredible list of 80 degrees.”

As the SSAF disintegrated, sailors aboard the light cruiser Yahagi continued to die when an abrupt break in the low clouds allowed the American pilots to mount a massive attack against the cruiser.

Takekuni Ikeda recalled what happened: “At 1330, [the Yahagi] was hit at the stern… [and] the ship started to make a continuous turn to starboard … [then] she stopped completely and began to drift in a swell…. Weapons fire from … American aircraft hit the motionless Yahagi again and again. I felt my whole body shaking heavily. Because of the damage to my eardrums, it was as if I were watching a silent movie. Columns of water jumped up around the ship, one after another, taller than the mast. Steam spouted from the cruiser’s funnel. The bloody odor of our dead and wounded sailors mixed with the smell of gunpowder.”

The Yahagi was doomed. Rear Admiral Keizo Komura, who commanded the destroyer squadron, realized that his flagship was sinking and decided to transfer his flag to a destroyer. He sent a signal to the Isokaze to approach, but little could be done because of the nonstop American attacks; the Isokaze was badly damaged by American bombs during her attempt to reach the Yahagi and was later scuttled by gunfire. Of her crew of 239, she suffered 20 dead and 54 injured. The destroyer Kasumi was also scuttled due to severe damage from American bombs. Of her crew of 200, she suffered 17 dead and 47 wounded.

Going Down With the Ship

The aerial assault continued without interruption. The third American strike force of 43 planes of Air Group 9––the final and most damaging attack––led by the Yorktown’s assault leader, Lt. Cmdr. Herbert Houck, arrived at about 1:45. Although accounts vary, it appears that three or more bombs decimated what was left of the Yamato’s superstructure and caused heavy casualties among what remained of her 25mm anti-aircraft gun crews. Three torpedoes, close together, slammed into the port side and caused the Yamato to resume what proved to be an inexorable roll to port as thousands of gallons of water rushed into her. This continuing roll to port exposed the battleship’s now-vulnerable starboard hull to attack as American planes continued their unrelenting strikes.

Counterflooding reduced the list to 10 degrees, but further list reduction required flooding the starboard engine and fire rooms. Many crewmen were trapped belowdecks and drowned by the ever-increasing torrent of water that was pouring in through the ripped hull and by the desperate counterflooding measures undertaken to save the ship. At 2:02, three bombs exploded amidships––about the same time as the much-too-late order to abandon ship was finally given as the Yamato was hit by additional torpedoes. The ship’s roll to port and sinking created a suction that pulled swimming crewmen back toward the ship and into her propellers. Each three-bladed propeller was nearly 20 feet in diameter.

The Yorktown’s planes showed the Japanese ships and sailors no mercy; for many of the pilots, it was payback for Pearl Harbor. At 2:05, the Yahagi, hit by 12 bombs and seven torpedoes, sank exactly one minute after the last bomb smashed into her. Out of a crew of 736 men, 446 men were killed and 133 injured.

In desperation, Ariga aboard the Yamato again ordered the starboard engineering spaces counterflooded; the counterflooding did no good. Worse, hundreds of men manning the battleship’s lower decks were thus sentenced to drown without being given the slightest chance of survival; Tsuboi stayed at his station until the order to abandon ship was given. He, like Kunimoto and Yoshida, would manage to swim clear.

Vice Admiral Ito did not survive. When he saw that he would not fulfill his mission, and that most of the men in his squadron were either dead or wounded, he shook hands and said farewell to the few of his remaining staff officers and started for his flag cabin to await the end. His adjutant, Lt. Cmdr. Ishida, followed behind him. It was Ishida’s job to wait on the admiral; now he wished to join the admiral in death, but the chief of staff forcibly stopped him. “You don’t have to go. Don’t be a fool.” Ishida hesitated, averted his face, and then gave in. He did not follow his admiral.

Ishida survived but Ariga did not. Having completed the final dispositions—the code books, the portrait of the emperor, and so on—Ariga, still in the anti-aircraft command post on the very top of the bridge and wearing his helmet and flak jacket, tied himself to the binnacle, the nonmagnetic housing for the ship’s compass. He did this so that his body would not be washed away when the Yamato sank; he wanted to go down with his ship.

He then issued a command for all hands to come on deck, shouted the Japanese cheer and battle cry banzai! three times, and then turned to the four surviving lookouts standing by his side. They were devoted to their captain and did not want to leave him, but Ariga would have none of this. He clapped each on the shoulder, encouraged them to be cheerful, and pushed them into the water. The fourth sailor pressed his last four biscuits into the captain’s hand, as if to show his deepest feelings. The captain took them with a grin. He was last seen eating the second biscuit when he and the Yamato disappeared in a huge explosion. (Captain Ariga was posthumously promoted two ranks to vice admiral in May 1945.)

Kunio Nakatani did not survive the Yamato’s sinking. Yoshida Mitsuru said of his American-born friend and shipmate: “Radio officer Ensign Nakatani must have died, too, at his post intercepting enemy communications. Because he was a Nisei, his conduct always attracted attention; I can guess that his death was as splendid as the deaths of his fellows.”

Death Blow to the Yamato

Also at 2:05, the Yamato’s list, which had increased to 15 degrees to port, was such that torpedoes set to a depth of 20 feet and fired into the Yamato’s starboard side smashed below the battleship’s armor and exploded directly into her vulnerable hull. (The Yamato’s 16.5-inch-thick armor plate formed a ledge along the outer hull; it tapered down to 3.9 inches at 20 feet below the waterline.)

Houck reported what happened: “I saw the runs and figured they got at least five hits. With the 20-degree listing, the torpedoes exploded right in the belly of the ship.”

From Houck’s statement, it appears that the Yamato was hit by at least eight torpedoes during this third raid. It was the death blow for the great ship. She capsized slowly, rolling over her port side. This was followed by a huge explosion at 2:23 which hurled most of the Yamato’s sailors into the sea or killed them outright. Houck took photographs with a wing camera and later recalled what he saw: “It made a mighty big bang. Smoke went up. The fireball was about 1,000 feet high.”

Houck was right—the explosion was a “mighty big bang,” and the resulting mushroom cloud, more than four miles high, was seen by sentries at Kagoshima, more than 124 miles away. Though nobody can be certain exactly what caused the explosion, it is speculated that one of the Yamato’s two bow magazines exploded, shattering the doomed battleship’s foresection in a tremendous blast. The Yamato sank quickly. Of her crew of about 3,332 men, 2,740 men died and 117 were wounded.

Not only was the great battleship gone, but the Yahagi and four of her eight escort destroyers had also plunged beneath the waves. All of the four surviving destroyers—the Fuyutsuki, Hatsushimo, Suzutsuki, and Yukikaze—suffered casualties, with a total of 72 men killed and 34 wounded. About 981 officers and men in the escort ships died while 342 more were wounded in the ill-fated suicide attack, an attack that never had the slightest chance of fulfilling its kamikaze mission, even by samurai standards.

The Americans lost 10 planes and 14 air crewmen; three others were injured. The world’s largest and most powerful battleship was destroyed in less than two hours by an unknown number of bombs and torpedoes.

Legacy of the Yamato

The story of the SSAF and the Yamato does not end on April 7, 1945. Over the years, successful efforts were made to locate the wreckage of the ship, and success was initially reported in 1985. The photographic records made during this successful first search were confirmed by one of the Yamato’s designers, Shigeru Makino, as showing identifiable remnants of the Yamato. The researchers reported that the wreck lies 180 miles southwest of Kagoshima, off the southern island of Kyushu, in more than 1,100 feet of water. The battleship is broken into two main pieces: a bow-to-midships section roughly 560 feet long and a 264-foot stern section.

In a society that seeks to atone for its warlike past, the Yamato remains a powerful influence in Japanese culture. Books and films about the ship and the SSAF have been produced, and museums and memorials to the behemoth, her crew, and the other doomed sailors of the ill-fated SSAF have been built. A television science-fiction series was created in which the wreck of the Yamato is used to create a starship bearing the same name. Some of the characters on the Starship Yamato bear the same names as their counterparts on the real Yamato.

Although an impressive Yamato Museum opened in 2005 in Kure with a huge scale model of the ship, there is a dark footnote to the SSAF story. The IJN held the SSAF survivors virtual prisoners when they returned to Japan. In an interview, Yamato survivor Kazuhiro Fukumoto said, “We were held in Kure for a month. So parents who knew about the Yamato sinking didn’t see their sons for a month and a half. They gave up, thinking that their sons had died.”

The destruction of the SSAF haunted the psyche of many of the survivors and their immediate families. On April 3, 2006, more than 280 remaining immediate family members and surviving veterans of the SSAF set sail on a commemorative memorial voyage and followed the same route as the SSAF, sailing to the exact locations where relatives and comrades perished on Y-1 Day, April 7, 1945. There had been similar memorial trips in 1987, 1994, and 1995, but in 2006, because the youngest survivor on the memorial trip was more than 80 years old, the families and survivors decided that 2006 would be the final year for the memorial voyage to honor those who died serving with the Special (Suicide) Attack Surface Force.

Yamato: “Of her crew of about 3,332 men, 2,740 men died and 117 were wounded.”

Wikipedia on USS Arizona: “The bombs and subsequent explosion killed 1,177 of the 1,512 crewmen on board at the time, approximately half of the lives lost during the attack”

Karma is a b*tch.

Dear Loring Chien,

I with great interest read you historical account of the sinking of the Yamato. One of favorite books is Mahan’s The History of Naval Warfare.

However, the reason I am contacting you is because of this:

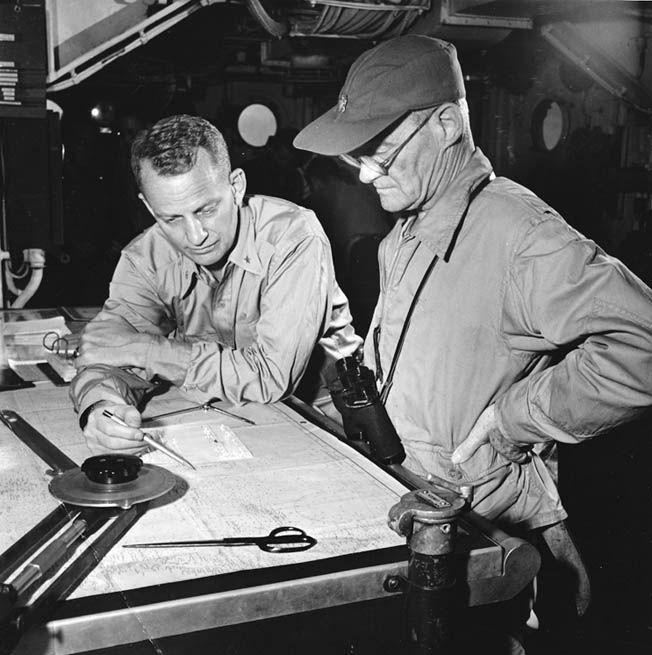

QUOTE: This is in the forward fire control room of the USS Wisconsin. My girlfriend’s grandfather served on the Iowa, New Jersey, and Wisconsin as an FCO …. UNQUOTE.

i was a NROTC Contract midshipmen that sailed on the 1957 Wisconsin Training Cruse – departing from Norfolk, passing through the Panama Canal and on to Chile and back again. It was a life changing experience of found memories. Regrettably, I do not have one picture of my life experiences on board the USS BB-64, Wisconsin. It is so difficult to try to explain, the respect, comradery and the hilarious initiation of crossing the Equator; to my wife, daughter, in-laws and grand children.

FYI I was planning on being a Navy pilot, but I did not stay in the NROTC after my second year because the Navy increased the required enlistment time from three to five years. Never the less the two years of Navy training was better that the “Personal Management” training I received at the Harvard Business. School. Many times, I think “I should have stayed in”. But I did not.

I went on to spend ten years in the Oklahoma Air National Guard, 137th Wing and became a 1st Lieutenant and Wing Training Officer.

If you, your girl friend or her father; have any pictures of life on board the Wisky, I would greatly appreciate emailing copies to me at: darrell@sino-texinternational.com

Thank you and yours truly,

Darrell Layne Vincent

P.S. Keep up the good work.