By Michael D. Hull

After two grueling months of action in the Pacific, Vice Admiral John S. “Slew” McCain’s powerful Task Force 38 retired in late November 1944 to the big Caroline Islands base of Ulithi Atoll for a 10-day breather.

No one needed a break more than Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey, the feisty, hard-drinking commander of the U.S. Third Fleet, who had come under fire for leaving San Bernardino Strait unguarded during the great Battle of Leyte Gulf on October 23-26, 1944. Pacing while “blue with rage,” Admiral Ernest J. King, chief of naval operations, had told Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander of the Pacific Fleet, that Halsey should be given a “rest.” General Douglas A. MacArthur, supreme commander of the Southwest Pacific Area, called for Halsey’s relief.

On the tiny northernmost island of Mogmog, Ulithi’s recreation center, McCain’s bluejackets joyfully swam, played baseball and basketball, pitched horseshoes, and swigged soft drinks and beer. Halsey, meanwhile, visited wounded sailors. He joked and shook hands with them, but it was an ordeal because he was torn by the suffering of his men. He tried to console himself at a wardroom party attended by hospital ship nurses. The event became well oiled and rowdy, climaxing when an officer doused a wastebasket fire with a bottle of carbon dioxide and then squirted a nurse between the legs. She screamed as the dry ice burned.

The Ulithi respite was soon over, and by Thanksgiving Day Halsey and Task Force 38 were dodging Japanese kamikaze assaults off the Philippines. Three aircraft carriers were damaged, including the veteran USS Intrepid. The volatile “Patton of the Pacific” had initially dismissed the suicide planes as “a sort of token terror, a tissue-paper dragon.” But his disdain gave way to anxiety as he watched his flattops burn. Halsey’s fortunes worsened by mid-December, but his next ordeal was not to come at the hands of the Japanese.

“Tropical Storm, Very Weak,”

Task Force 38 embarked from Ulithi on December 11, 1944. The fast carrier fleet had replenished, and its defensive tactics had been revised because of the increasing kamikaze threat. The armada comprised Task Group 38.1 commanded by Rear Admiral Alfred E. Montgomery, Task Group 38.2 led by Rear Admiral Gerald F. “Jerry” Bogan, and Task Group 38.3 commanded by Rear Admiral Forrest C. Sherman. Ninety ships set sail, including 13 carriers, eight battleships, three heavy cruisers, seven light cruisers, three antiaircraft cruisers, and 56 destroyers. McCain was aboard the carrier USS Hancock, and Halsey was in his flagship, the 45,000-ton battleship New Jersey. Both vessels were part of Task Group 38.2.

Plans called for the flattops to hit Luzon to support General MacArthur’s imminent invasion of Mindoro and then to make an unprecedented foray into the South China Sea to sever Japan’s remaining shipping lanes to the East Indies. The latter operation had long been sought by Halsey, but it was delayed because of the need for air support in the invasion of Leyte.

On December 13, the fast carriers topped off from their shadowing oilers and headed in toward the Luzon coast. Fighter sweeps started at dawn on the 14th and continued for three days. When the flattops withdrew on December 16, their fighters and dive bombers had destroyed 269 Japanese aircraft, sunk merchant ships, and blasted airfields and railroads. Twenty-seven American planes were lost. Enemy air opposition to the Mindoro landings was minimal, and none of the fast carriers were attacked.

Admiral Halsey planned to refuel his ships at sea on Sunday, December 17, and commence another three-day fighter strike on the 19th. Early on the morning of the 17th, TF-38 rendezvoused with 12 fleet oilers escorted by destroyers, destroyer escorts, and five escort carriers about 500 miles east of Luzon. Three days of high-speed operations had left many of the task force’s ships critically low on fuel.

The vessels began refueling on schedule at 10 am on the 17th, but a 20-30-knot wind and a cross swell made the operation difficult. “The wind,” said Admiral Robert B. “Mick” Carney, Halsey’s chief of staff, “was across the sea and it was impossible to find a course which would prevent yawing and surging.” On the previous day, Commander George F. Kosco, the Third Fleet aerologist, had received reports from Ulithi and Pearl Harbor of a “tropical storm, very weak,” and had informed Halsey and Carney. Kosco could not pinpoint the storm, but he did not think it would be anything serious.

An Erratic Storm

At 11:07 am on December 17, the destroyer USS Spence eased alongside the New Jersey to start fueling. When Halsey and his staff sat for lunch in the flag mess, they were alarmed to see the Spence rolling excessively on the starboard side, and it seemed that she might be slammed against the flagship. “She was riding up ahead,” reported Halsey later, “and she’d drop well astern and charge ahead and drop astern…. She was pitching and rolling heavily.”

Commander Kosco calculated that the “tropical storm” was coming closer to the fleet than he had estimated and was increasing in intensity. The swells mounted, and at 11:27 am the fueling hoses parted on the Spence. Disturbing reports came in from task group commanders. The destroyers Healy and The Sullivans experienced steering problems, and hoses parted aboard the Collett, Stephen Potter, L.K. Swenson, Preston, Thatcher, and Manatee. A seaman on the Caperton fractured his leg when seas smashed over the forecastle.

At 12:51 pm, when the storm’s center was 120 miles southeast of the task force’s position, Halsey ordered a halt to the fueling operations, planning to resume them at 6 the next morning. “No warning of the typhoon was received up to this point from any outside source,” he said later. “The storm followed an erratic course, different … and contrary to available history of December typhoons.”

Halsey called a conference in the flag mess, where lunch dishes were cleared and maps and charts spread out. Kosco placed in front of the admiral his morning’s weather map, which indicated a storm center 400 miles southeast of the task force and moving toward it. He expected that the “tropical disturbance” would merge with a weak cold front and veer off to the northeast. Aboard the carrier Lexington, however, Admiral Bogan was sure that a severe storm was approaching, while Captain Jasper T. Acuff, commander of the TF-38 replenishment group, was the first to make the correct guess as to the storm’s position and course. He and two escort carrier skippers agreed that the fueling rendezvous set for 6 am on December 18 would be directly in the storm’s path. Captain Michael H. Kernodle of the carrier San Jacinto had received storm warnings for 24 hours, but the information was not passed on to Kosco.

The weather continued to worsen as Halsey and his aides pored tensely over their maps, struggling to make a course toward calmer water. The assignment to support MacArthur on the 19th meant that TF-38 must refuel no later than the morning of the 18th. During the evening of December 17, the task force and its oilers butted steadily westward through mounting seas. At midnight, Halsey ordered a change of course from due west to due south, hoping to reach smoother water. Unwittingly, he was taking the armada directly into the path of the approaching typhoon.

“We Were Completely Cornered”

At dawn on Monday, December 18, Halsey realized that fueling would be even more difficult than on the previous day. But it had to be attempted because of the Luzon combat commitment and for the safety of the smaller vessels in the task force. With their fuel tanks almost empty, the destroyers were riding higher in the water and becoming unseaworthy. But prevailing conditions made the operation impossible. Halsey had no choice but to halt the fueling just after 8 am and send a dispatch to General MacArthur saying that TF-38 would not be able to support him the next day.

The storm soon assailed the task force and its support ships with howling winds and blinding rain. The fleet was by then 180 miles northeast of Samar in the eastern Philippines. The sea heaved, foam sloshed across decks, and vessels canted sickeningly, wallowing under tons of water. Some ships lost steering control, and sailors were reported washed overboard. Few men in the fleet had seen anything like the storm’s fury.

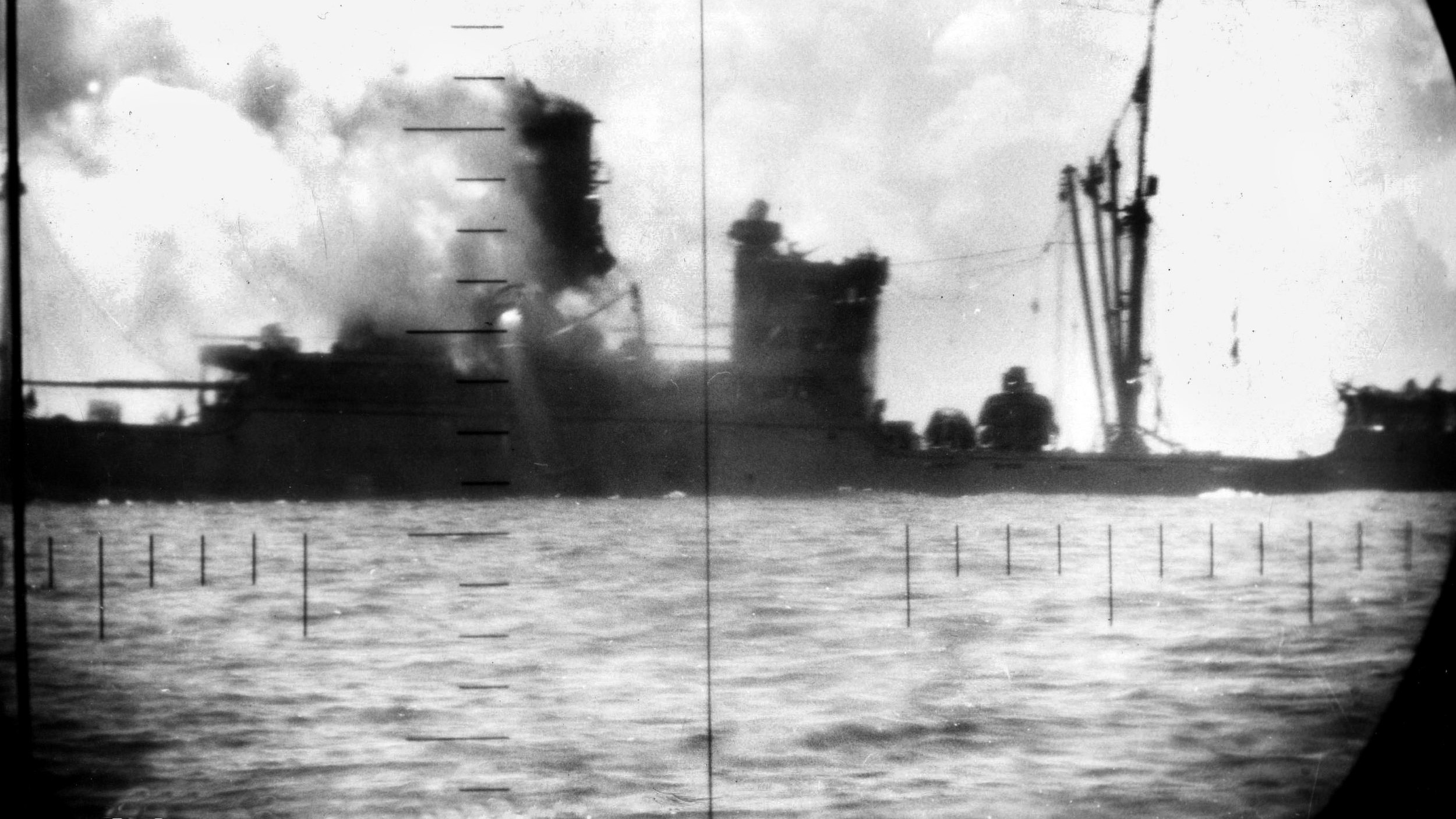

The fleet and “jeep” carriers rolled heavily. Planes were swept from the flight decks, while others broke loose in their hangar decks, slamming against bulkheads and catching fire. Efficient firefighting was impossible. The carrier Monterey lost steerage way, the carrier Independence lost two men overboard, and the escort carrier Kwajalein temporarily lost steering control. The carrier Cowpens lost seven planes, the Monterey 18, and the San Jacinto eight. Nineteen floatplanes were blown off the battleships and cruisers, and a total of 146 aircraft were lost during the storm.

“We were completely cornered,” Halsey reported. “The consideration then was the fastest way to get out of the dangerous semicircle and to get to a position where our destroyers could be fueled.” He sent a warning to all ships and weather stations at 9:14 am. “We didn’t think that we were dealing with a storm as severe as a typhoon until we were within 100 miles of it,” said Commander Kosco. Admiral McCain ordered changes in course and advised ships to disregard formation keeping and take the best courses and speeds for security.

As the barometer fell rapidly, the wind velocity rose sharply to 73 knots while 70-foot waves battered the ships from all sides. Some destroyers heeled over on their beam ends with their funnels almost horizontal. Water surged into their intakes and ventilators, shorting circuits, killing power, and leaving them adrift.

The ships rose and fell in the mountainous seas. The mighty New Jersey hung in the troughs and then slowly righted herself, lurching and laboring to the tops of swells. “No one who has not been through a typhoon can conceive its fury,” reported Halsey. “The 70-foot seas smash you from all sides. The rain and the scud are blinding; they drive you flat-out, until you can’t tell the ocean from the air…. At broad noon, I couldn’t see the bow of my ship, 350 feet from the bridge…. This typhoon tossed our enormous ship as if she were a canoe…. We ourselves were buffeted from one bulkhead to another; we could not hear our own voices above the uproar.” Admiral Carney voiced “grave doubts” that the battlewagon would survive, while Halsey feared for the fate of the destroyers. “What it was like on a destroyer one-twentieth the New Jersey’s size I can only imagine,” he said.

He was right. The smaller ships were the worst hit, and the destroyer crews underwent a nightmare as the rising winds and seas tossed their craft around like toys. Caught near the storm center, the Hull, Spence, and Monaghan capsized and sank with practically all hands.

Surviving the Sinking Ships

Water Tender Second Class Joseph C. McCrane was one of only six survivors of the USS Monaghan, which had rammed and sunk a Japanese midget submarine at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and fought in the Aleutians. He reported, “The storm broke in all its fury. We started to roll, heaving to the starboard, and everyone was holding on to something and praying as hard as he could. We knew that we had lost our power and were dead in the water…. We must have taken about seven or eight rolls to the starboard before she went over on her side.”

It was later believed that the three destroyers went down because their oil and ballast were out of trim as a result of the interrupted refueling operation. Though damaged, the destroyer escort Tabberer managed to rescue 41 Hull survivors and 14 from the Spence.

The typhoon raged on, with the ships—now strewn across about 2,500 square miles—tossing, heeling over, and drifting with no way to escape. The storm reached its height between noon and 2 pm. The wind increased to 83 knots with gusts reaching 93 knots.

Many of the Third Fleet ships suffered varying degrees of damage. They included the carriers Cowpens, Monterey, San Jacinto, Kwajalein, Cabot, Altamaha, Nehenta Bay, and Cape Esperance; the light cruiser Miami; the destroyers Dewey, Aylwin, Buchanan, Dyson, Hickox, Maddox, and Benham; the destroyer escorts Tabberer, Melvin R. Nawman, and Waterman; the oiler Nantahala, and the fleet tug Jicarilla.

An estimated 790 officers and men were lost or killed, and scores of others injured. Task Force 38 was as severely battered as if it had been in a major battle.

Thankfully, the winds abated and the skies cleared late in the afternoon of that harrowing Monday. Halsey promptly dispatched ships and planes to search for survivors, and the operation lasted for three days. Lone swimmers were picked up, and sometimes raft loads. Destroyers rescued 54 men who had been aboard the Hull, 24 from the Spence, and 16 from the Monaghan. The search, said Halsey, was “the most exhaustive in naval history.”

The shaken Third Fleet regrouped and finally fueled on December 19, and then steamed westward toward Luzon the following day. Predawn air strikes in support of MacArthur’s invasion were planned on the 21st, but the seas became increasingly heavy and the typhoon was then passing over Luzon. Halsey and his staff agreed that the operation could not be conducted successfully, so MacArthur and Nimitz were notified. Early on December 24, the ships entered Ulithi harbor. The weary crews were allowed some much needed rest while a service squadron started repairing the damaged vessels.

Investigating the Loss of Halsey’s Ships

Nimitz, who had been promoted to fleet admiral 10 days before, was hosted by Halsey at a festive Christmas Eve dinner aboard the New Jersey. The admirals and their staffs then spent much of Christmas Day in conference. Nimitz, meanwhile, had appointed a court of inquiry to investigate the loss of the Hull, Spence, and Monaghan, and to find out why Halsey’s fleet had been caught by the typhoon.

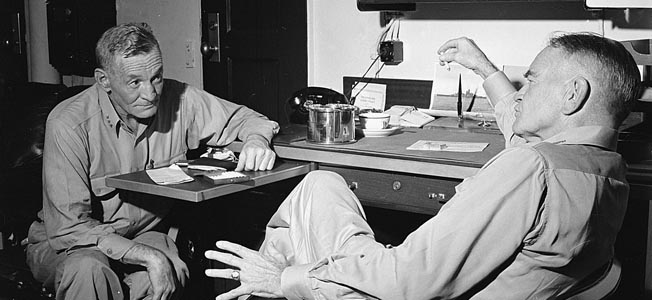

Comprising Vice Admirals John H. Hoover and George D. Murray and Rear Admiral Glenn B. Davis, the court of inquiry convened aboard the destroyer tender USS Cascade, anchored in Ulithi harbor, in the last week of December 1944. The witnesses included Halsey, McCain, Bogan, Sherman, and Kosco, and the testimony was lengthy and complex. Halsey was blamed for the damage and ship losses, but no negligence was found, only the “stress of war operations” and “a commendable desire to meet military commitments.”

Halsey stressed that he had received no “timely warning” of the typhoon and strongly criticized the Pacific Fleet’s meteorological system. The court put the “preponderance of responsibility” on Halsey and cited his “large errors” made in predicting the location and path of the storm, but it concluded that the “aerological talent” assisting him was “inadequate in practical experience and service background in view of the importance of the services to be expected and required.”

The court of inquiry recommended action to “impress upon all commanders the necessity of giving full consideration to adverse weather likely to be met in the Western Pacific, especially the … formation and movements of typhoons.” Nimitz promptly approved the court’s findings, and Admiral King concurred. At the court’s suggestion, Nimitz called for three weather ships to be stationed in the Western Pacific, the deployment of weather reconnaissance planes, and for the Bureau of Naval Personnel to make more experienced aerological officers available to the Pacific Fleet. The Navy improved its weather service.

Admiral Nimitz also sent a letter to his fleet stressing the need for safety at sea, with much advice for dealing with severe weather conditions. “The time for taking all measures for a ship’s safety is while still able to do so,” he wrote. “Nothing is more dangerous than for a seaman to be grudging in taking precautions lest they turn out to have been unnecessary. Safety at sea for a thousand years has depended on exactly the opposite philosophy.”

The typhoon was to provide the climactic sequence in Herman Wouk’s blockbuster 1951 novel, The Caine Mutiny, and the 1954 film masterpiece directed by Edward Dmytryk and starring Humphrey Bogart, Fred MacMurray, Van Johnson, Robert Francis, Jose Ferrer, E.G. Marshall, and Arthur Franz.

Typhoon Connie: Halsey’s Second Storm

Halsey characteristically wasted no time in December 1944 commiserating over the tarnishing of his outstanding service record and got busy with the plans for air strikes against Formosa, Okinawa, and Luzon in support of MacArthur’s invasion at Lingayen Gulf on January 9, 1945. The admiral did not mention the court of inquiry to his staff except in a series of proposals for improving the weather reporting service and did not refer to it in his 1947 autobiography, although he recounted the typhoon. To him it was just “water over the dam.”

Hewing to his motto, “Hit hard, hit fast, hit often,” Halsey led his mighty Third Fleet in harm’s way during the first half of 1945 as Allied naval, ground, and air forces relentlessly pushed the Japanese back toward their home islands. After supporting MacArthur’s operations on Leyte, Luzon, and throughout the Philippine area, the fleet made a broad sweep through the South China Sea on January 10-20 and destroyed huge amounts of enemy shipping. In May, Halsey began planning operations against the Japanese homeland. His hatred of the enemy had not dimmed. “Before we’re through with them,” he had remarked, “the Japanese language will be spoken only in hell.”

But, in his last campaign of the war, the costly April 1-June 22, 1945, battle to capture Okinawa, Halsey would again fall victim ironically to the fearsome enemy he had faced six months before—another typhoon. After hoisting his flag in the 45,000-ton battleship USS Missouri at Guam on May 18, Halsey headed for Okinawa to relieve Admiral Raymond A. Spruance’s Fifth Fleet. On the barren, 60-mile-long island, soldiers and Marines of Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner’s U.S. Tenth Army were struggling to overcome fierce Japanese resistance while naval units offshore withstood many kamikaze attacks. Aerial support was provided by McCain’s Task Force 38, which comprised Task Group 38.1 commanded by Rear Admiral Joseph J. Clark; Sherman’s Task Group 38.3, and Task Group 38.4 led by Rear Admiral Arthur W. Radford. McCain flew his flag in the carrier Shangri-La.

After sending Sherman’s group to Leyte for a rest period, Halsey ordered Radford’s force northward on June 2 to strike the airfields on Kyushu, the southernmost Japanese main island. Halsey and McCain remained with Clark’s group off Okinawa. When Radford returned on the afternoon of June 3, Halsey sent Task Group 38.1 southeast to rendezvous with Rear Admiral Donald B. Beary’s Service Squadron 6. Ships and search planes, meanwhile, reported a tropical storm moving up from the south.

The Missouri and Shangri-La headed southeast with Radford’s group, and Halsey ordered the amphibious command ship Ancon to monitor the storm. On the evening of June 4, Task Group 38.4 joined Clark’s force and Beary’s fueling squadron, and they all headed east-southeast. At this time, radar operators aboard the Ancon sighted the typhoon, but the ship’s report did not reach Halsey until 1 the next morning. Later reports indicated that the typhoon was heading rapidly northeast, almost directly toward the Third Fleet.

Course changes were made, and there was much feverish plotting aboard the Missouri and other ships through the night and into the early hours of Tuesday, June 5. Halsey did not want his fleet scattered as before, and he hoped to find better weather so that his flattops could fend off kamikaze attacks. But the barometer was falling, and the howling typhoon closed in. While Radford’s group steamed through fairly calm seas 15 miles to the north, Task Group 38.1 was sucked into a maelstrom of high winds and mountainous waves. Clark ordered his ships to stop their engines and heave to.

Beary’s fueling group, meanwhile, struggled against 75-foot waves and wind gusts up to 127 knots as it passed through the eye of the typhoon. His 48 ships were “riding very heavily,” he reported, yet only four—two jeep carriers, a tanker, and a destroyer escort—received serious damage. Clark’s group passed through the eye half an hour after Beary’s, and almost all of his 33 ships suffered some damage. But none were sunk. The cruiser Pittsburgh had 110 feet of her bow section torn off, and Clark’s four carriers—the San Jacinto, Hornet, Bennington, and Belleau Wood—were battered. Clark and Beary lost six men killed or swept overboard and four seriously injured. Seventy-six planes were lost.

The other TF-38 ships damaged in the typhoon included the battleships Missouri, Massachusetts, Indiana, and Alabama; the escort carriers Windham Bay, Salamaua, Bougainville, and Attu; the cruisers Baltimore, Quincy, Detroit, San Juan, Duluth, and Atlanta; 11 destroyers; three destroyer escorts; two oilers, and an ammunition ship.

Challenging Halsey’s “Extremely Ill Advised” Change of Course

Aware that he would have to face another court of inquiry, Halsey took the offensive. In an angry message to Admiral Nimitz, he complained that early-warning messages were garbled, that weather estimates conflicted, and that coding regulations critically delayed the Ancon’s message. The Third Fleet, meanwhile, soon went back into action. On June 6, 1945, Clark’s and Radford’s groups again provided air support off Okinawa, and Radford’s carriers resumed strikes against Kyushu on the 8th. U.S. troops gained the upper hand on Okinawa, the kamikaze attacks tapered off, and TF-38 retired to Leyte Gulf on June 13 after 92 wearying days at sea.

Admirals Halsey, McCain, Clark, and Beary were ordered to appear before a court of inquiry aboard the aging battleship USS New Mexico anchored in San Pedro Bay, a Leyte Gulf inlet. Presided over again by the harsh Admiral Hoover, the tribunal convened on June 15 and deliberated for eight days. Blame was placed squarely on Halsey and McCain, with the court concluding that the main cause of the Third Fleet’s damage was Halsey’s “extremely ill advised” change of course from 110 to 300 degrees at 1:34 am on June 5. McCain, Clark, and Beary were indicted because “they continued on courses and at speeds which eventually led their task groups into dangerous weather, although their better judgment dictated a course of action which would have taken them fairly clear of the typhoon path.”

Hoover recommended the reassignment of Halsey and McCain, and Navy Secretary James V. Forrestal was reportedly ready to retire Halsey. When the court’s finding reached the Navy Department, Admiral King agreed that the two officers had been inept and, with the weather data available to them, should have avoided the typhoon. But Halsey was a national hero, and King had no wish to humiliate him. It would tarnish the Navy’s triumph in the Pacific. King decided to take no action, and Forrestal agreed.

McCain, however, received no such consideration. Nimitz had long doubted his competence, and it was decided that it was time for him to go. He was ordered by the Navy Department on July 15 to hand over command of Task Force 38 to Admiral John H. Towers and, after a furlough, become deputy head of the Veterans Administration. But McCain, worn out and emaciated, died of a heart attack on the day after he returned to his Coronado, California, home.

Halsey, meanwhile, sailed back to America and was greeted in San Francisco and Los Angeles by blaring bands, sirens, whistles, and cheering thousands. His reputation had been tarnished, yet he emerged from the war as a fighting admiral revered by the men who served under him.

That picture of the Langley rolling to port. Wrong. That’s to starboard

In the old photos, the Langley’s bridge appears to be on the port side after she was converted to a seaplane tender in 1937, so she would be coming toward the camera, rolling to port in that picture from 1944.

The Langley in this picture is CVL-27. She is rolling to starboard. USS Langley CV-1 in your reference was scuttled and sunk in Feb 1942.

Poorly written full of questionable language. Obvious desire to denigrate Admiral Halsey. An admiral in a battle situation does not do all jobs and does not make single autonomous decisions. King seems to have made all the correct decisions in his career as a commanding admiral but then King never sent men in to combat or battle with little assurance of a positive outcome. Fletcher’s problems originated with indecision and a desire to be slow and methodical. Other commanders were slow and methodical but not many were fighters. Spruance scored in Midway but spent the rest of the war quiet and roaming the sidelines as it were. Weather was unpredictable and not much of a science in WW. II.

I’m not sure what language you found questionable, but I am certain the author did not intend to denigrate Halsey. Did you read the last sentence of the story? “His reputation had been tarnished, yet he emerged from the war as a fighting admiral revered by the men who served under him.”

“Spruance scored in Midway but spent the rest of the war quiet and roaming the sidelines as it were.”

LOL. I guess Truk, the Marshalls, the Gilberts, the Mariannas, Iwo Jima and Okinawa were just picnics, right? By far Spruance was the better commander and was more respected by the officers under him than Halsey who wasn’t a great planner and made a huge tactical error chasing toothless IJN carriers leaving the Leyte beaches and support ships defenseless. He was almost relieved twice for errors in judgement, as was noted above, and in my opinion, didn’t deserve a fifth star. But he was the more popular at home because of his aggressive demeanor and had much better relations with the press. Spruance wasn’t one to toot his own horn but his list of accomplishments far outshine Halsey’s and he ended up as the commander of the Pacific Fleet after the war. One other thing. During the surrender ceremony in Tokyo Bay, Nimitz wanted Spruance to stay on his flagship off Okinawa in case Japan tried anything funny. It was Nimitz that trusted Spruance the most operationally. The fact that he didn’t get a fifth star is, in my mind, an egregious wrong by the USN.

Halsey proved to be impulsive and impatient to the point of recklessness at times. Leaving the Leyte invasion force unguarded while not knowing the intentions of the Japanese center force was a serious error. The invasion force was saved only by the courage and tenacity of the smaller forces left behind and the Japanese commander losing his nerve. I’ve often wondered how Midway would have played out had he been in command. I fear not as well as it did with Spruance. He likely would have charged right into Yamamoto’s main force lying in wait behind the attack force. Anyway, I have read that King and McArthur wanted him relieved after the typhoon incidents but his old friend Nimitz protested due to their close friendship and for past support.

Also, though Halsey is not a meteorologist he is ultimately responsible for all operations of the task force. They saw the storm on radar from a distance, so how is it possible they steamed right through the middle of it. Some very questionable seamanship at best.

And the beat goes on. With the passage of another decade

or two, the role of Halsey will continue to be debated. I am

not yet convinced that the irrepressible admiral was

professionally qualified nor could he be expected to make

sound sound judgements about adverse weather when the

science of meteorology in 1945 had not yet recognized the

existence of the jet stream. If you will ask any long resident in

Florida about the anticipated course of an approaching

hurricane 24 hours in advance, they will likely tell you, it is too

soon to know. And they would be correct.

I would note two quick points. I went through a typhoon in the Philippines. It is near impossible to predict its course in more than a highly generalized estimate. It is why there are so many casualties in the country when todays modern weather service, the PAGASA, can give only a general blanket warning. Re Halsey’s tactics. The condition of the Japanese Navy and the number of capital ships available to it at the time required rather different tactics than the hard charging that made Halsey’s fame earlier on. I believe it was Sun Tzu that said something about changing tactics in changed situations.