By David Alan Johnson

At exactly 6:45 on the morning of October 25, 1944, Rear Admiral Clifton A.F. Sprague received a message from one of his pilots on antisubmarine patrol. The admiral recalled that the message went something like this: “Enemy surface force of 4 battleships, 7 cruisers, and 11 destroyers sighted 20 miles northwest of your task group and closing in on you at 30 knots.”

Admiral Sprague, nicknamed “Ziggy,” was annoyed by the message. He was certain that the sighting report was a case of mistaken identity. “Now, there’s some screwy young aviator reporting part of our own forces,” he said to himself with no small amount of exasperation. The “enemy surface force” was probably just part of Admiral William F. Halsey’s fast battleship group. Actually, Halsey’s Third Fleet was miles away to the north.

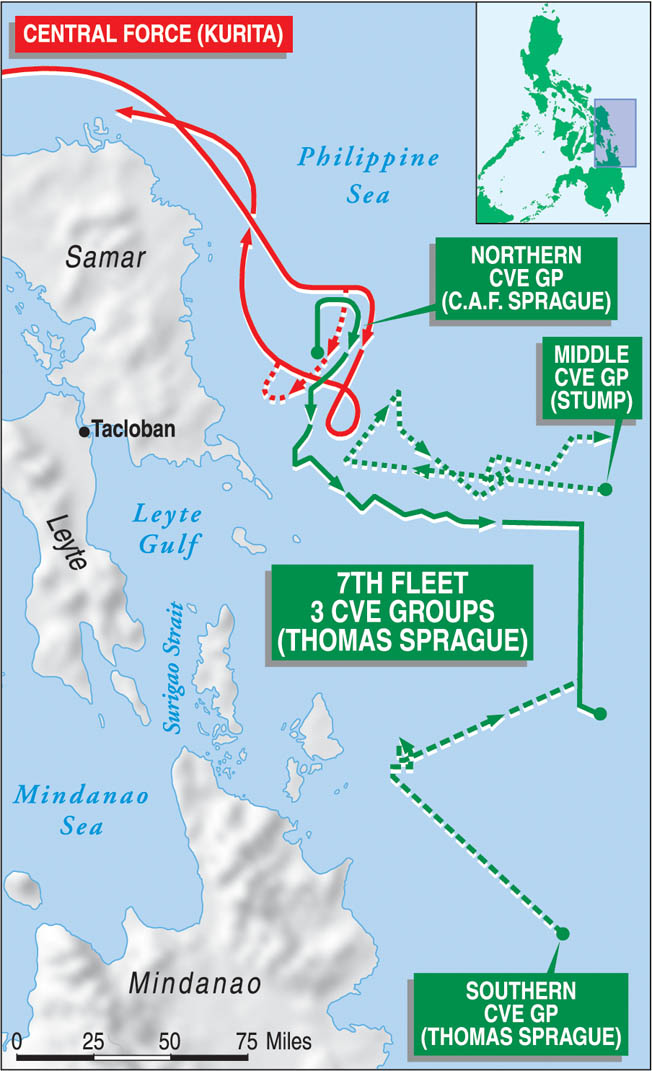

Admiral Sprague shouted into the squawk box, “Air plot, tell him to check his identification,” and went back to work. His six escort carriers, screened by three destroyers and four destroyer escorts—officially known as Task Group 77.4.3, but usually referred to by its call sign, “Taffy 3”—had been flying support strikes for the recent landings on the Philippine island of Leyte for the past eight days. Taffy 3 was operating just east of Samar Island, and Sprague had another full day of patrols and air strikes to schedule.

Three minutes after the first report, Sprague received another message from the pilot who made the first report. “Identification of enemy force confirmed,” he radioed. “Ships have pagoda masts.”

At about the same time, a thick pattern of antiaircraft puffs began bursting off to the northwest—another confirmation that the surface force was not Admiral Halsey’s battleships. Enemy gunners were shooting at the pilot who had just spotted them. The pilot, Ensign William C. Brooks of Pasadena, California, was returning the compliment, dropping his payload on an enemy cruiser. The only trouble was that the ensign’s payload consisted of two depth charges—hardly effective weapons against an enemy cruiser. This attack could be seen as a symbol of the battle that was to come—an American David confronting a Japanese Goliath, armed with not much more than a slingshot.

The force that Brooks had sighted was the middle section of a three-pronged Japanese advance against the American landing beaches at Leyte Gulf. Admiral Takeo Kurita’s Center Force, which was made up of four battleships, six heavy cruisers, two light cruisers,

and 11 destroyers, had been hit by air strikes from Halsey’s Third Fleet in the Sibuyan Sea the previous day. Although Kurita had initially withdrawn his force after Halsey’s fleet had damaged several Japanese warships and had sunk the battleship Musashi, he reversed course and made his way through the San Bernardino Strait during the night. Many senior American officers reached the conclusion that Kurita was retreating from the battle, but that was not the case.

Shortly after Ensign Brooks confirmed that the approaching warships were Japanese, Sprague’s lookouts were able to provide visual confirmation—the unmistakable superstructures of Japanese cruisers and battleships began popping over the northwestern horizon. At 6:58, the ships opened fire. Less than a minute later, colored splashes from the Japanese shells landed astern of Taffy 3. Each Japanese warship used a different color dye marker, which allowed them to spot their own shells and make targeting adjustments.

Admiral Sprague’s command, Taffy 3, was made up of six escort carriers: Fanshaw Bay, St. Lo, White Plains, Kalinin Bay, Kitkun Bay, and Gambier Bay along with three destroyers, Heermann, Hoel, and Johnston, and four destroyer escorts, Dennis, J.C. Butler, Raymond, and Samuel B. Roberts. Kitkun Bay and Gambier Bay were actually a separate carrier division, under Rear Admiral Ralph Ofstie, although they were still part of Taffy 3. The heaviest armament on any of these ships was the 5-inch batteries aboard the destroyers and destroyer escorts. Each of the escort carriers also had one 5-inch gun. This was clearly no match for Kurita’s force, which included the 18-inch guns of Musashi’s sister ship, the giant battleship Yamato.

“Wicked salvos straddled the USS White Plains, and then colored geysers began to sprout among all the other carriers,” Sprague later reported. “In various shades of pink, green, red, yellow and purple, the splashes had a kind of horrid beauty.” A seaman aboard the White Plains remarked, “They’re shooting at us in Technicolor!”

Sprague was fully aware of his predicament and did not think that his force of “baby flattops” and their escorts would last 15 minutes against the oncoming battleships and cruisers. As soon as the approaching task force was confirmed as Japanese, he “took several defensive actions in quick succession.” He ordered a change in course from north to due east, which pointed Taffy 3 “at full speed toward a friendly rain squall nearby.” The new course also turned his carriers into the wind, and at 6:56 Sprague ordered all carriers to begin launching aircraft for torpedo and bombing attacks against Kurita’s force. A minute later, he ordered the carriers and their escorts to make as much smoke as possible to screen Taffy 3 from the Japanese gunners. A smokescreen offered scant protection against large-caliber enemy shells, but it was better than nothing.

The carriers began launching their aircraft as soon as it was practical. Admiral Sprague’s flagship Fanshaw Bay, called “Fannie Bee” by her crew, sent her full complement of Grumman TBF Avengers off first, armed with torpedoes. White Plains began by launching Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters and brought her bomb-carrying Avengers up to the flight deck after the fighters were in the air.

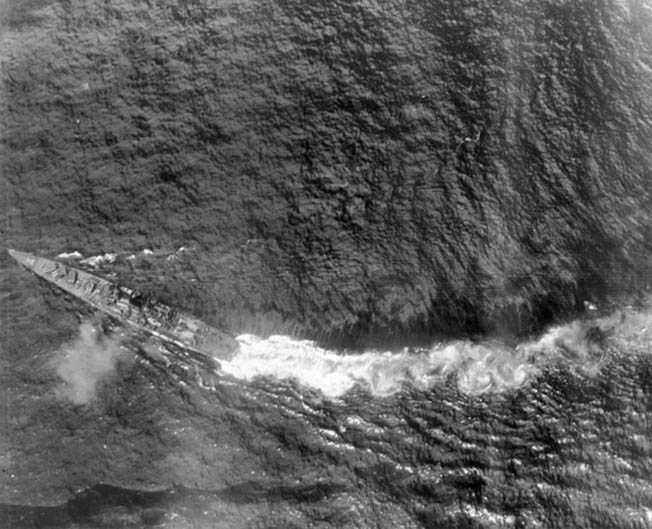

It would have made very little difference to Sprague at that particular moment, but Kurita was having some harrowing thoughts of his own. When lookouts aboard Yamato first spotted the American ships at 6:44, he was as surprised as Sprague by the encounter. No one aboard Yamato could see that the carriers of the enemy task force were escort carriers and not fleet carriers. Kurita had already seen what American carriers could do and was shaken by the unexpected sight of still more of them off Samar.

He ordered his force to deploy from sailing in columns on course 170 to a circular antiaircraft formation on course 110. Before the command could be carried out, Kurita changed his orders, this time to “General Attack,” which threw his entire fleet into confusion. “No heed was taken of order or coordination,” his chief of staff reported. Instead of forming a battle line with his four battleships and six heavy cruisers, which would have allowed Kurita to bring all of his big guns to bear, he scattered his ships and his firepower. Because of the general attack order, each Japanese ship would operate independently, which dispersed Kurita’s advantage in gunnery.

Sprague did not know anything about Kurita’s confusion. He only knew that he had a large enemy force bearing down on his lightly armored carriers and escort vessels. At 7:01, he broadcast an urgent request, in plain language, for assistance. Admiral Thomas Stump, commander of Taffy 2, responded immediately. Taffy 2 was the nearest carrier force to Sprague, about 30 miles away. Admiral Thomas Sprague (no relation to Ziggy Sprague) also sent aircraft from Taffy 1, about 70 miles away. Admiral Stump sent words of encouragement to his friend. “Don’t be alarmed, Ziggy,” he shouted over the TBS (Talk Between Ships), “Remember, we’re in back of you—don’t get excited—don’t do anything rash!” His voice went up a level or two every time he spoke, making the officers on Fanshaw Bay’s flag bridge smile in spite of themselves.

The attacking Avengers went in singly or in small groups. They did not have time to form up in a coordinated attack. Whether they carried torpedoes or bombs, the Avengers made their runs without the benefit of strafing fighters to run interference for them.

By 7:30, just about every one of Taffy 3’s operational aircraft had been launched. The heavy cruiser Suzuya was one of the first Japanese warships to come under attack. The cruiser was hit several times and, according to one report, was “slowed down.” All aircraft in the Leyte Gulf area were ordered to attack Admiral Kurita’s Center Force. Six Avengers armed with torpedoes and 20 fighters attacked at 8:30, along with aircraft that had already been launched from the escort carriers.

But these planes were very hurriedly armed and launched and had no time to coordinate their movements, either. Even so, their attacks were aggressive and constant. Most of the Avengers were armed with torpedoes until the supply of torpedoes ran out. Then they were sent out with bombs—any kind of bombs that were available, including 100-pound all-purpose bombs that were designed for hitting small land-based targets.

After they dropped their bombs, the pilots made dry runs on the enemy ships to distract the Japanese gunners. The commander of Gambier Bay’s air group flew his Avenger through enemy flak for two hours after he dropped his bombs. The pilots of the Wildcat fighters were sent in to strafe “with the hope that their strafing would kill personnel on the Japanese warships, silence automatic weapons, and, most important, draw attention from the struggling escort carriers.” When their ammunition ran out, the fighter pilots also resorted to dry runs to harass the enemy. One pilot made 20 strafing runs, 10 of them without ammunition.

Five planes of Gambier Bay’s air group circled the Japanese fleet for 20 minutes looking for a hole in the clouds that would allow them to make their runs against the big ships. While they were waiting for their chance, the pilots watched a group of Avengers and Wildcats going after the battleships. “The attacks were well executed,” observed the flight leader. But there were too few aircraft, and the Avengers had bomb loads that were too dissimilar, usually too light, to do any real damage.

Japanese officers were inclined to disagree with this assessment. “The bombers and torpedo planes were very aggressive and skilful and the coordination was impressive,” a Japanese officer told his American interpreter after the war, “even in comparison with the many experiences of American attacks we had already had, this was the most skilful work of your planes.”

In addition to his carrier’s air groups, Sprague also sent his destroyers and destroyer escorts against Kurita’s force. The normal job of these screening warships was to protect the escort carriers from submarines, but now they would be performing a completely different task.

The Johnston, under Commander Ernest E Evans, was a Fletcher-class destroyer (along with Heermann and Hoel) and would be one year old in two days’ time. Evans opened fire at 7:10; his target was the Japanese cruiser Kumano. Johnston fired more than 200 rounds at the cruiser, and numerous hits were observed. The Japanese ships returned fire. Enormous splashes of four or five different colors erupted around the destroyer.

American warships had a distinct advantage in gunnery over the Japanese due to the radar-controlled Mark 37 Fire Control System and the Ford Mark I Fire Control Computer. The radar-directed system gave Johnston efficient firing solutions for her 5-inch guns, which allowed her gunners to hit their target repeatedly in spite of the greater range of the enemy warships. Japanese gunners had to rely on their colored dye markers from initial salvos to find the range.

Evans also gave the word to begin a torpedo attack. Sprague had ordered all three destroyers to attack with their torpedoes, and Johnston would go in with Heermann and Hoel. Because Johnston was closest to the enemy, she was the first to attack, closing to within 10,000 yards of Kumano. She fired her full complement of 10 torpedoes, which were observed to run hot, straight, and normal. When all torpedoes had been fired, Evans reversed course and retired behind a smokescreen.

“Two and possibly three heavy underwater explosions were heard by two officers,” reported another officer from Johnston, “at the time our torpedoes were scheduled to hit.” The leading enemy cruiser emerged from the smoke about a minute later, her stern section burning furiously. Most reports mention two or three torpedoes striking Kumano, but Kurita acknowledged only one hit from an American destroyer. Kumano dropped out of the fight. The heavy cruiser Suzuya, which had been hit by bombs and was traveling at a speed of 20 knots, also withdrew.

At 7:30, Johnston was finally hit by three 14-inch shells and three 6-inch shells. These hits knocked out the after fire room and engine room, cut all power to the steering engine and the three after 5-inch guns, and rendered the gyrocompass useless. The ship’s speed was reduced to 17 knots. Its radar antenna snapped off its mast, crashing into the bridge and killing three officers. All of Evans’ clothes above his waist were blown off, along with two fingers of his left hand. Many sailors stationed below decks were killed.

But the destroyer did not sink, and all stations answered “aye” to bridge inquiries. The same rain squall that covered the escort carriers now passed over Johnston, giving her crew about 10 minutes to repair some of the damage. Japanese gunners depended on optical rangefinders, and their shooting tended to be ineffective when their target was obscured by rain, clouds, or smoke. Three of Johnston’s 5-inch guns would be back in action in a short time.

Hoel’s target was the battleship Kongo. Hoel’s captain, Commander Leon S. Kintberger, began firing at the enemy battleship at 14,000 yards. Kongo fired back, hitting Hoel’s bridge and knocking out all voice and radio communication. Two minutes after opening fire with her 5-inch guns, Hoel launched a half-salvo of five torpedoes at the battleship. Kongo managed to avoid the torpedoes by making a hard left turn at 7:33.

American torpedoes were not fast and were easily avoided. However, the evasive action not only slowed the advance of the Japanese warships but also created confusion. Admiral Kurita himself said, “Major units [warships] were separating all the time because of the destroyer torpedo attacks.” He realized that he was losing more tactical control every time his ships had to turn to avoid Taffy 3’s torpedoes.

While her torpedoes were still running their course, Hoel was struck by several heavy caliber shells. The destroyer’s port engine was knocked out along with three guns, and the rudder was jammed hard right. Before her rudder could be brought amidships, Hoel found herself heading straight for Kongo. While steering was being corrected, her number one and two guns continued to fire at targets of opportunity.

Even though the destroyer was badly damaged, Kintberger did not withdraw from the battle. He fired the rest of his torpedoes at the heavy cruiser Haguro, the leading ship in the straggling cruiser column. All five torpedoes ran straight toward their target, and “large columns of water were observed to rise from the cruiser at about the time scheduled for the torpedo run.” Japanese records do not confirm that any of Hoel’s torpedoes struck the cruiser.

After launching the last of his torpedoes, Kintberger did his best to withdraw to the southwest, away from the enemy’s big guns. But the destroyer only had one engine, the battleship Kongo was only 8,000 yards off his port beam, and heavy cruisers were only 7,000 yards off his starboard quarter. Hoel was boxed in and did not have enough speed to get away.

“Every Japanese ship within range took a crack at her,” according to one report. Hoel zigzagged for over an hour, and her two bow guns fired about 500 rounds of 5-inch ammunition at whatever enemy ship seemed the most menacing. At the same time, she received more than 40 hits herself, 5-inch, 8-inch, and even 16-inch. The shells were armor piercing, and some went right through without exploding. But these unexploded shells punched the destroyer full of holes, including many below the waterline. The Japanese heavy cruisers passed close enough that Hoel’s crew was able to observe their antiaircraft gunners at work.

At 8:30, an 8-inch shell knocked out the remaining engine, leaving Hoel dead in the water. The ship began flooding and settling by the stern. Kintberger saw no alternative to giving the order, “Prepare to abandon ship.” Some crewmen stayed behind to make sure that no explosion would occur—No. 1 magazine was on fire—while the destroyer was being abandoned. At 8:55, after all the men left the ship, Hoel finally rolled over and sank. Japanese ships continued firing at her until the end.

The last of the three American destroyers, Heermann, did not hear the order to join Hoel and Johnston in the torpedo attack. She had been busy screening the escort carriers and just did not get the word. The order finally did get through at 7:50, and Heermann went charging off at full speed through the carrier formation, or what was left of it. Visibility was not the best, owing to both the smoke and the rain. The destroyer’s captain, Commander Amos T. Hathaway, had his hands full. Twice Hathaway had to signal his engine room to go to emergency astern to avoid a collision. As it was, Heermann narrowly missed both Hoel and the destroyer escort Samuel B. Roberts.

After literally steering clear of all nearby friendly vessels, Hathaway straightened his course and headed toward the nearest enemy warship, which happened to be the heavy cruiser Haguro. Heermann began shooting at the cruiser with her 5-inch guns and launched seven torpedoes at 7:54. Actually, the attack was supposed to be only a five-torpedo salvo, but the torpedoman accidentally fired two extras. Haguro dodged all of the torpedoes and opened fire on the Heermann. All of the cruiser’s salvos missed their target.

Hathaway turned away from Haguro after firing his torpedoes and headed toward Kongo and Haruna. Astern of these two battleships were Yamato and the fourth Japanese battleship, Nagato. Enemy warships seemed to be at every point of the compass, but more enemy warships meant more targets, at least as far as Hathaway was concerned. He turned to course 270 to get into a firing position for the rest of his torpedoes and shifted his 5-inch guns to the cruiser Chikuma.

While Heermann had Chikuma under fire, Kongo, Nagato, and Yamato were targeting Heermann. Red, yellow, and green shell splashes erupted all around her, but she was not hit by anything larger than shell fragments. After maneuvering to avoid the big guns of the battleships, Heermann was only 4,400 yards away from Haruna. At 8 am, Hathaway launched his remaining three torpedoes at Haruna, opened fire with his 5-inch batteries, and broke away.

All of this frantic activity happened within a matter of minutes—between 7:50, when Hathaway began his high-speed run past Taffy 3’s escort carriers, and 8:03, when he turned away from Haruna. It was a lucky 13 minutes for Heermann; the ship had not been hit by enemy gunfire, even though she had been the target for several Japanese warships.

Heermann’s action report claims that one of her torpedoes hit Haruna, but two of the torpedoes missed their mark and headed for Yamato along with two torpedoes that had probably been fired by Hoel at another Japanese ship. Yamato turned away to evade the torpedoes, heading north and keeping on that course for about 10 minutes. This effectively took Yamato out of the fight. Kurita had lost his biggest battleship, as well as what should have been his most effective gun platform, at the height of the battle.

Kurita was becoming convinced that he was facing a major American task force, not just a few escort carriers and destroyers. However, the battle was far from over. At about the same time that Hoel was firing her torpedoes at Haguro, Sprague ordered his destroyer escorts to begin their runs at Kurita’s warships: “Little Wolves form up for a second attack,” he barked. “Wolves” was code for the destroyers, while the radio call sign for the destroyer escorts was “Little Wolves.” So far, the destroyer escorts had been assigned almost exclusively to antisubmarine patrols. Torpedo attacks against cruisers and battleships were something new to Taffy 3’s Little Wolves.

They threw themselves into the task. Raymond took on Haguro, the leading Japanese cruiser. Just before 8 am, she launched three torpedoes at a range of about 6,000 yards. Haguro turned to avoid them while Raymond changed course and got away from the scene as quickly as possible.

Dennis followed the same course of action. She fired her torpedoes at the nearest Japanese cruiser, either Chokai or Tone, and turned sharply to the southwest. At about 8:10, Dennis opened fire with her after 5-inch battery on a cruiser that was already under air attack. After exchanging gunfire with the cruiser for about seven minutes, Dennis wheeled off to the southwest at high speed.

As soon as they made their torpedo attacks, all of the Little Wolves reversed course and headed southwest, making smoke and firing their 5-inch guns at the nearest enemy ship. None of the little ships were hit by enemy gunfire, and there were no collisions, which is nothing short of miraculous considering the fact that all of them were turning and swerving to avoid enemy salvos.

Nobody on either side had anything resembling a clear overall view of what was taking place. The weather was not helping—rain and clouds reduced visibility and sometimes blocked it altogether. Smoke from the destroyers, destroyer escorts, and escort carriers further obscured visibility.

Japanese officers still had no real idea of what they were facing. At first the escort carriers of Taffy 3 were identified as carriers of Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet. Some lookouts identified them as Japanese carriers. Others imagined that they saw cruisers and even battleships. Both Haguro and Tone reported firing on a “heavy cruiser”—actually the Johnston—and Haguro opened fire on a “destroyer”—actually the Raymond.

Japanese gunners began to register hits on the American escort vessels. At about 8:50, Dennis received a direct hit from Tone. The shell went through the main deck and out the starboard side about three feet above the waterline. Ten minutes later, she had her 40mm gun director knocked out by a second hit and a third hit struck her No. 1 5-inch gun shield, rendering the gun inoperative. Since the destroyer escort had already lost her No. 2 gun to mechanical trouble, she altered course to 220 and retired to the southwest.

Samuel B. Roberts was hit at about the same time and received three more in rapid succession. At about 9 am, her captain, Commander R.W. Copeland, reported a “tremendous explosion” with the impact of two 14-inch shells fired by Kongo. The explosion blew a long, jagged hole 30 or 40 feet long and about seven to 10 feet high in the destroyer escort’s port side, right at the waterline. It wiped out No. 2 engine room, burst the after fuel tanks, and started fires on the fantail. The order to abandon ship was given at 9:10. Samuel B. Roberts rolled over and sank at 10:05. Of her crew of eight officers and 170 men, three officers and 86 men were killed, missing, or died of wounds.

Gambier Bay managed to outmaneuver everything the Japanese fired at her for about 30 minutes. The carrier changed course every time an enemy salvo fell, confusing enemy gunners and making them correct their aim. From 7:41 to 8:10, the range between Gambier Bay and the enemy cruisers decreased from 17,000 yards to 10,000 yards.

At 8:10, the escort carrier received her first hit, which started fires on the flight deck and in the hangars. From that point, she was hit continuously. The forward port engine room was holed below the waterline, flooding the forward spaces and causing the engine room to be abandoned. The ship slowed to 11 knots and dropped astern of the rest of the group.

Johnston reentered the fight at about this time. Commander Evans saw what was happening to Gambier Bay and told his gunnery officer to begin firing on the nearest cruiser, which happened to be Chikuma. His idea was to draw her fire away from the escort carrier. “We closed to 6,000 and scored five hits,” according to Johnston’s gunnery officer, but the tactic did not work. Chikuma ignored the destroyer and kept firing at Gambier Bay. Johnston’s gunnery officer thought it was stupid for Chikuma to concentrate on the escort carrier. “He could have sunk us both.”

Heermann also did her best to distract Chikuma, but she had no luck either. Although the big cruiser did shift some of her fire to Heermann and managed to hit the destroyer, her primary target continued to be Gambier Bay. Steering was knocked out, radar was disabled, and the carrier’s engine room flooded. By 8:45, Gambier Bay was dead in the water and sinking.

Five minutes later, the order was given to abandon ship. Chikuma and another cruiser kept firing, killing men in the water with shell fragments, until the carrier finally capsized and sank at 9:07.

After Gambier Bay sank, Johnston turned her attention to Japanese destroyers that were moving into position to attack the escort carriers. The destroyers were sighted when they were still more than 10,000 yards away. Johnston immediately opened fire on the leader, which was actually the light cruiser Yahagi. The enemy fired right back, hitting Johnston several times, according to one account. Johnston hit Yahagi about 12 times, and the cruiser turned 90 degrees to starboard to get into position to fire torpedoes.

Yahagi fired seven torpedoes at 9:05, and the Japanese destroyers began launching shortly afterward. They were too far away from their target. The nearest carrier, Kalinin Bay, was 10,500 yards distant. The squadron commander’s decision to launch torpedoes was premature; he was rattled by Johnston’s determined attack. The Japanese action report states, “Three enemy carriers and one cruiser were enveloped in black smoke and observed to sink one after the other” as a result of the attack. This was nothing but wishful thinking.

Actually, the torpedoes had no effect at all—every one missed. One was deflected by an accurate shot—some would say a lucky shot—from St. Lo’s 5-inch gun. Another was detonated by strafing from one of St. Lo’s Avengers. The others were evaded, their runs toward the escort carriers so long that the targets had more than enough time to get out of the way.

“Thus,” according to historian Samuel Eliot Morison, “one damaged destroyer, which had expended all her torpedoes and lost one engine, managed to delay, badger, and disconcert a Japanese destroyer squadron.”

Johnston’s captain, Commander Evans, was absolutely elated over what he had accomplished. “Now I’ve seen everything,” he chuckled.

But Evans did not have much time to celebrate. After the Japanese destroyer squadron fired its torpedoes, it turned its attention to Johnston. The destroyer was hit by what has been described as “an avalanche of shells.” All power and communications were lost, and only the No. 4 5-inch gun, which was being operated manually, could return fire.

“There were two cruisers on our port, another dead ahead of us, and several destroyers on our starboard side,” one of Johnston’s officers recounted. And the Japanese destroyers circled around her, shooting at her “like Indians attacking a prairie schooner.” At 9:40, Johnston went dead in the water. Five minutes later Evans gave the order to abandon ship. When the destroyer went down shortly after 10:10, the captain of one of the Japanese destroyers saluted. It was one of the few acts of gallantry shown that morning.

Losses were not entirely one sided. The cruiser Chokai was hit by a 5-inch shell, possibly from White Plains, which set off eight of the ship’s Long Lance torpedoes. The resulting explosion knocked out the cruiser’s rudder and damaged her engines, slowing her down and causing her to drop out of formation. A flight of Avengers completed the damage, scoring five bomb hits amidships, one hit and two near-misses near the stern, and three hits on the bow. One of the pilots observed the heavy cruiser “to go about 500 yards, blow up and sink within five minutes.” A report from Haguro puts the cruiser’s sinking at 9:30.

An air strike from Admiral Stump’s Taffy 2 accounted for the cruiser Chikuma. Stump claimed that his torpedo bombers scored hits on two cruisers. Tone’s action report states that Chikuma was “knocked out” by a torpedo attack at 8:53.

Kurita lost two cruisers but still had more than enough firepower to sink what was left of Taffy 3. His battleships and cruisers had been firing at the American escort carriers since before 8 am. Kalinin Bay received a direct hit at 7:50. Fanshaw Bay was hit by four 8-inch shells with a loss of three killed and 20 wounded. White Plains was damaged by a 6-inch salvo, and Kitkun Bay had several men wounded by shell fragments. Kalinin Bay was hit by no fewer than 13 8-inch shells and almost certainly would have gone down if it had not been for the determination of her damage control team. Holes below the waterline were plugged, power was restored, and steering control was done by hand from far below decks. The carrier remained afloat.

Nobody aboard any of Taffy 3’s carriers or escort vessels had any idea that Admiral Kurita’s destroyer attack, which had been short-circuited by Johnston, was the last Japanese offensive action of the morning. At 9:25, while he was preoccupied with dodging torpedoes on the bridge of Fanshaw Bay, Sprague heard one of his signalmen shout, “Goddammit boys, they’re getting away!”

Sprague looked to see what all the shouting was about. “I could not believe my eyes, but it looked as if the whole Japanese fleet was retiring.” He admitted, “It took a whole series of reports from circling planes to convince me.”

It was true. Kurita had decided to break off action. At 9:25, he ordered: “Rendezvous, my course north, speed 20.” His intention was to regroup his scattered warships and take stock of damage before resuming course toward Leyte Gulf. But as the morning went on, and as he thought about the air and surface attacks he had suffered at the hands of Taffy 3, the prospect of going back toward Leyte Gulf became less appealing.

Kurita hovered in the vicinity of the morning’s battle for more than 31/2 hours, changing course several times—from due north to west to southwest to west again, then back to southwest, and finally to due north. At about 1:10 pm, it was apparent that he was heading away from the Leyte landing beaches and the vulnerable American transport craft offshore, which had been his intended target early that morning.

Kurita’s decision to withdraw was based on a lack of solid information. No one was able to give him any reliable information on the true makeup of Taffy 3. His staff officers kept insisting that it must be a part of Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet and that the escort carriers were either Ranger-class or Independence-class aircraft carriers. Also, the optical rangefinders aboard the Japanese ships were not able to track Taffy 3’s carriers. Some reports stated that the escort carriers were making 30 knots, possibly an optical illusion. The little escort carriers were built on Liberty Ship hulls and had an optimistic top speed of about 18 knots.

To make a bad situation even worse, Yamato’s two spotter planes failed to return; they had been sent out to reconnoiter Leyte Gulf. Their loss deprived Kurita of a vital source of information. A report that the admiral did receive at 9:45 only added to his confusion. A mysterious enemy task force was spotted only 113 miles north of Suluan Island, off the coast of Samar. And the plain language calls for help—there was more than one—made him fear the worst. After the war, he admitted that he had been influenced in deciding to withdraw by hearing this plain-language transmission, which led him to believe that powerful American surface units were on the way to reinforce the ships he was attacking.

Kurita had received a severe beating from Halsey’s Third Fleet the day before and had no desire to repeat the encounter. From what he knew, as well as from what he imagined, he might very well be doing just that if he remained off Samar. At 12:36, Kurita signalled Tokyo: “First Striking force has abandoned penetration of Leyte anchorage. Is proceeding north searching for enemy task force. Will engage decisively, then pass through San Bernadino Strait.” The enemy task force he was searching for did not exist. This was the mysterious fleet that was reported at 9:45.

Sprague had no insight into Kurita’s motives. He only knew that a large Japanese fleet, which by rights should have sunk his entire force and gone on to attack the landing force at Leyte Gulf, had inexplicably turned away. The battle was summed up by one historian: “In a running fight lasting almost two hours and a half, six escort carriers and their screen of three destroyers and four destroyer escorts, aided by planes from Stump’s escort carrier unit, has stopped Kurita’s powerful Center Force, and inflicted greater loss than they sustained.”

Sprague himself had this to say about what had happened off Samar. “The failure of the enemy main body and encircling light forces to completely wipe out all vessels of this task unit can be attributed to our successful smoke screen, our torpedo counterattack, continuous harassment of enemy by bomb, torpedo and strafing air attacks, timely maneuvers, and the definite partiality of Almighty God.”

The action for Taffy 3 that day was not over. At about 10:50, five kamikazes from an air base on Luzon attacked Sprague’s carriers while they were recovering aircraft. The suicide planes approached at low altitude and never showed up on radar. Kitkun Bay was badly damaged by a bomb from one of the Japanese aircraft, although the kamikaze itself bounded off the port catwalk and splashed harmlessly into the sea.

St. Lo was not as fortunate. One kamikaze, a Zero fighter, crashed through the flight deck and exploded below. Torpedoes and bombs that had been brought up to the flight deck began exploding, setting the entire length of the carrier on fire. At 11:25, St. Lo went down under a dense cloud of smoke. St. Lo has been originally commissioned as USS Midway, but had her name changed when Midway was given to one of the new fleet carriers. Old timers blamed St. Lo’s misfortune, after surviving the big guns of Admiral Kurita’s Center Force, on the carrier’s renaming. Everyone knew that changing the name of a ship was sure to bring bad luck.

Morison wrote fittingly of Taffy 3’s fight: “In no engagement of its entire history has the United States Navy shown more gallantry, guts and gumption than in those two morning hours between 0730 and 0930 off Samar.”

Author David A. Johnson has written numerous articles on a variety of World War II topics. His recent book Yanks in the RAF is now available through Prometheus Books.

From when I first read about this battle (I was about 16 then), I am breathless at the courage, self-sacrifice, and determination of the sailors and airmen who fought this battle.

It’s not only one of the most amazing stories of the US Navy, or naval history, but of all-time combat history.

If ever there was an example of “It’s not the size of the dog in the fight, it’s the size of the fight in the dog,” this is it.

I always thought this would make a great movie.