By William E. Welsh

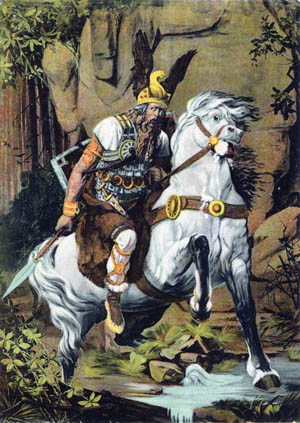

The Saxon warriors worked tirelessly from dawn to dusk atop the mountain felling trees, cutting them into logs, and adding them to the field fort they were building on a flat spur of the Suntel Mountains in the heart of their homeland. Widukind, a Westphalian chieftain who ruled the Saxon warriors, had ordered them to fortify on the Hohenstein, a spur on the north side of the Suntel ridgeline. He wanted his men to be ready if the Franks suddenly attacked. The Saxon rebellion in the summer of 782 was widespread. Carolingian King Charlemagne, who sought to subjugate them, not only wanted to convert them to Christianity but also wanted to send Christian priests to live among them. What is more, the Frankish king planned to require the Saxons to pay tithes to support the church and the priests whose job it was to baptize the pagan Saxons. As if this were not enough, Charlemagne planned to procure large parts of the Saxon wilderness as part of his royal domain.

The Frankish initiatives were an enormous affront to the Saxons, and warriors from Westphalia, Angria, and Eastphalia snatched up their spears and shields and flocked to Widukind’s new fortress by the hundreds. The wily rebel leader planned to use the stronghold as a base from which to assail Frankish forts and monasteries in eastern Francia and Hesse.

Saxons loyal to the Franks informed them of Widukind’s mountaintop fortress and his intention to resume raiding towns and abbeys. Coincidentally, a column of Frankish heavy cavalry was marching west to punish the Slav Sorbs for raiding Frankish-held Thuringia. When the commanders of the column learned of Widukind’s plans, they dismissed the Saxon auxiliaries attached to their force and counter marched to meet the bigger threat to Frankish security. A clash was inevitable. Saxon foot soldiers were no match for Frankish heavy cavalry, so Widukind deemed it essential for his men to entrench and await the inevitable Frankish assault.

The Franks had begun converting to Christianity in the late 5th century, but the pagan Saxons, who were the last group of pagans in so-called inner Germany, continued to worship multiple gods. In the mid-6th century, Frankish King Chlotar I imposed an annual tribute on the Saxons of 500 cows. Several generations later, Frankish King Dagobert rescinded the tribute in return for assis- tance in fighting the Slavs.

In the final years of the 7th century, some Saxons had begun expanding into Frankish-co trolled Hesse. This was part of a quest to leave the marshlands of the lower Rhine, Weser, and Elbe Rivers for the drier uplands south of Saxony. The Franks viewed this as a serious encroachment on their territory.

In 738 Charles Martel, Charlemagne’s grandfather, who had risen from the powerful position of Mayor of the Palace of both Austrasia and Neustria to become the de facto king of the Franks during the last four years of his reign, had designated Anglo-Saxon monk Boniface the archbishop of all of Germany east of the Rhine. Significantly, Boniface assisted the Franks in establishing a handful of fortified monasteries in Hesse during his lifetime, including Fulda, Fritzlar, Hersfeld, Amo- nenberg, and Buraburg. At the time of his last raid in 737, Martel informed the Saxons that hence- forth he would require them to pay taxes to the Carolingian crown. Pepin the Short, who was Charlemagne’s father, continued the Frankish tradition of punitive expeditions against the Saxons.

Pepin had left explicit instructions that after his death his eldest son Charlemagne was to rule the northern part of the Carolingian realm and his second son Carloman the southern part. Fol- lowing the death of his brother Carloman in 771, after which Charlemagne became the sole king of Francia, he began the forcible conversion of the Saxons to Christianity. The Franks had grown weary of the Saxons’ annual raids against the settlements on the eastern border of their realm. During their bloody forays, the Saxons carted off gold, silver, and precious objects. They also murdered priests and monks at abbeys established by Saint Boniface and his followers in the early 8th century.

When the Frankish sword was against their throat, the Saxons would swear oaths of loyalty. To get the Saxons to abide by their oaths, the Carolingian rulers demanded that they give hostages to the Franks to guarantee their oaths. Much to the Franks’ frustration, the Saxons routinely broke their sworn oaths even though the hostages’ lives were forfeit if the oaths were broken. Charlemagne eventually came to realize after a decade of fighting the Saxons that it was necessary assimilate the Saxons into Frankish society.

Charlemagne’s biographer Einhard, author of the 9th-century work Vita Karoli Magni (Life of Charles the Great), succinctly captured the challenges facing Charlemagne in subjugating the Sax- ons. “Our boundaries and theirs touch almost everywhere on the open plain … so that on both sides murder, robbery, and arson were of constant occurrence,” wrote Einhard. “The Franks were so irritated by these things that they thought it was time to no longer be satisfied with retaliation but to declare open war against them.”

Dealing with the Saxons was problematic, for they had no monarch with whom Charlemagne could negotiate. Instead, the Saxons were organized in tribes under chieftains. The two peoples’ value systems were several centuries apart and there seemed to be no way to breach the wide gulf between the cultures.

When the Franks rode into Saxony, it was if they had stepped back in time. There were nei- ther cities nor roads. The Saxons lived in wattle huts in small settlements scattered throughout the heavily forested north German plain.

While in his prime, Charlemagne campaigned annually. He typically held an annual assembly between March and May at one of his Aus- trasian palaces and afterward embarked on a major military expedition to punish or conquer an adversary as the situation required. During the protracted Saxon Wars, the annual assembly was occasionally held in Hesse. The Carolingians often were engaged in more than one offensive military expedition at a time, and Charlemagne frequently had to delegate an expedition to a trusted subordinate commander so that he could personally lead the most important expedition.

Charlemagne also wanted to convert the Saxon pagans to Christianity as a way to further the interests of the powerful Church of Rome. Charlemagne would allow himself to be deceived during the 770s into believing that he had succeeded in subjugating the Saxons and putting them on a path to Christianity. What he failed to consider was the difficulty of transforming the religious and social customs of a fiercely independent people. It ultimately would take Charlemagne 32 years to completely conquer and assimilate the Saxons. “Never was there a war more prolonged or more cruel than this, nor one that required greater efforts on the part of the Frankish peoples,” wrote Einhard.

The Carolingian king held his annual assembly in the Rhine River city of Worms in the spring of 772. His most powerful nobles attended the gathering at which Charlemagne made the case for invading Saxony in a puni- tive raid during which one of the key objectives would be the destruction of the pagan shrine known as the Irminsul. The Irminsul was a wooden pillar in a grove in southern Saxony that served as a symbolic representation of the column in Saxon mythology that held up the universe. Charlemagne’s intention was to destroy the Irminsul to show the Saxons that their Gods—Woden, Thor, and Saxnot—could not protect them against the Franks and that Christianity was a stronger religion than their paganism. Weary of Saxon raids, the nobility of Austrasia enthusiastically agreed to the armed expedition.

A large Carolingian army crossed the Rhine River at Mainz in July and marched north approximately 80 miles to the Saxon stronghold of Eresburg. After a successful assault on Eres- burg, the army marched a short distance to the Irminsul, which was located in a grove and surrounded by the residences of pagan priests. The Franks were delighted to find that the caretakers of the shrine had failed to remove large stores of gold and silver, which the attackers eagerly plundered.

Contemporary Frankish sources are conflicted as to how the shrine was destroyed. Some accounts state that it was simply cut down by soldiers with axes. The Royal Frankish Annals, however, advances a far more intriguing method of destruction. The author of the annals con- tends it was destroyed by flood as the result of an act of God. Charlemagne “wished to stay there two or three days in order to destroy the temple completely, but they had no water,” writes the Annalist. “Suddenly at noon, through the grace of God, while the army rested and nobody knew what was happening, so much water poured forth in a stream that the whole army had enough.” If this account is accepted, then the Franks may have cut down the pillar and then diverted a stream to flood the site so that it could no longer be used by the Saxons as a holy site. Charlemagne met with local Saxon nobles, accepted a dozen hostages as an act of good faith, and withdrew his army, hoping the pagans had learned a lesson.

The Saxons had no intention of honoring any pledge made under duress. What is more, they were irate over the destruction of the Irminsul. The rebellion that erupted the following year succeeded because it was well led and because Charlemagne was absent from the region while campaigning in Lombardy. The Saxons, facing a major external threat, united under Widukind. The Saxon guerrilla leader not only had the backing of the various Saxon tribes, but also had alliances in place with the Frisians and Danes. During a whirlwind counterattack, the Saxons retook Eresburg and assaulted the Frankish fortresses of Buraburg on the Eder River in north central Hesse and Syburg on the Austrasian-Westphalian border. Charlemagne was tied up besieging Pavia in Lombardy throughout the winter of 773-774 and unable to return to Austrasia. Widukind and his rebels struck again in the spring of 774, massacring monks at the Benedictine Abbey of Fritzlar on the Eder.

Upon returning in the fall of 774, Charle- magne went to his palace at Ingelheim on the Rhine to plan a quick strike against the Saxons. Four columns were dispatched, three of which “fought the Saxons and, with God’s help, had victory,” states the Annalist. During the quick strike, Charlemagne retook Eresburg, but the onset of winter called a halt to further cam- paigning. By that time, Charlemagne had resolved to begin the gradual annexation of Saxony. He believed that the only way to end the Saxons’ annual raids and convert them to Christianity was under the iron thumb of the Franks.

Charlemagne summoned his royal officials and leading nobles to the palace at Quierzy in January 775 to plan a major invasion that involved fighting in various locations between the Rhine and the Weser. The Carolingian king was determined to complete the conquest of the Saxons. The Carolingians marched up the Moselle Valley two months later and turned north at Koblenz. They drove a small force of Saxons out of Syburg and continued east to Eresburg. When Frankish scouts reported that a Saxon army was at Braunsberg on the east bank of the Weser River approximately 50 miles northeast of Eresburg, Charlemagne conducted a forced march to fall upon the Saxons before they could withdraw to the safety of the deep forests on both sides of the north-flowing Weser. The Franks won a decisive victory over the Saxons at Braunsberg.

At that point in the 775 campaign, Charlemagne divided his army into two columns. He led one column east into Eastphalia to find and destroy any hostile forces, and a Frankish commander whose name is not recorded led a group north into Westphalia with the same objective. Charle- magne achieved his objective without incident. When he reached the town of Orhum on the Oker River, the Carolingian king met with Hessi, the chieftain of the Eastphalians. Hessi, who had no standing force with which to fight the Franks, pledged an oath of loyalty to Charlemagne and turned over hostages to guarantee his pledge.

Meanwhile, the other Frankish column had detailed orders to clear the Weser Valley of any rebel group it encountered. The mounted column followed the Weser north, moving for many miles through thick forests until they eventually entered the marshy lowlands of northeastern Westphalia. They bivouacked near the Saxon settlement of Lubbecke to decide their next move.

Unknown to them, the wily Widukind was leading a band of Westphalians that had been shadowing the Frankish column. The following morning, the Franks sent out a forage party. When it returned with what it had procured from the Westphalians, a group of Saxons disguised as Franks followed the returning foragers and infiltrated the camp’s perimeter. Once inside the camp, “the Saxons attacked the sleeping or half-awake soldiers and are said to have caused quite a slaughter among the multitude who were off guard,” wrote the Annalist. “But they were repulsed by the valor of those who were awake and resisted bravely.” Badly shaken by the guerrillas’ ability to infiltrate their supposedly secure camp, the Frankish commander sent a messenger to request assistance from Charlemagne. The Annalist’s disgust is evident in his summation of the failed probe into Westphalia. “The men acted carelessly, and were tricked by Saxon guile,” he wrote.

Charlemagne ordered the commander of the force in Westphalia to hold his ground until the two Carolingian columns were reunited. Charlemagne marched west, crossed the Weser, and stopped for a short time at Buckegau where he met with Angrian chieftain Brun. Like Hessi, Brun also pledged an oath of loyalty to Charlemagne and turned over hostages to the Carolingian king. The Franks subsequently converted the hostages to Christianity and used them as pawns in their relent- less push to convert the pagan Saxons. Shortly afterward, the two Frankish columns united at Lubbecke. Charlemagne was eager to punish the Westphalians for their guerrilla attack. He sent scouts to scour the surrounding area, and they located Widukind’s force. The reunited Carolingian army clashed twice with Widukind’s rebels. The first clash was a draw, and the second one a decisive victory for the Franks. Unfortunately, Widukind slipped away. He travelled north to Denmark where his close ally King Sigfred protected him from the Franks.

In the autumn of 775, Charlemagne cleared the Westphalian Hellweg, the main road connect- ing the lower Rhine with Thuringia, of any threat from armed Saxons. The Westphalian Hellweg ran from the confluence of the Rhine and Ruhr Rivers through the Lippe Valley to the middle Elbe River. The Franks would soon strengthen their defenses in the eastern end of the Lippe Valley with the construction of a fortress near Pader Springs that they named Karlsburg in Charlemagne’s honor. By the close of the 8th century, the Frankish settlement in the area would expand to include a royal palace and become the seat of the Bishopric of Paderborn.

Charlemagne held his annual assembly in May 777 at Pader Springs. He informed the Ripuar- ian and Saxon nobles in attendance that he intended to divide Saxony into bishoprics. Having established a church at Paderborn, Frankish priests and monks baptized large numbers of pagan Saxons. Conspicuously absent from the assembly was Widukind, who bided his time in Denmark waiting for another chance to disrupt the Frankish subjugation of the Saxons.

The Carolingian king led a great army into the Iberian Peninsula in 778. On his return to Austrasia, Charlemagne learned that Widukind had assembled a large Saxon army east of the Weser River. The Saxons’ first objective was the new Frankish fortress of Karlsburg. They defeated the garrison and destroyed the fortress. Afterward, the rebel army marched southeast to Deutz, a Frankish-held town on the right bank of the Rhine River, which they sacked and burned. “The rebels advanced as far as the Rhine at Deutz, plundered along the river, and committed many atrocities, such as the burning of the churches of God in the monasteries and other acts to loathsome to enumerate,” wrote the Annalist.

Widukind’s rebels then engaged in a running battle with the Frankish garrison from Koblenz, which sought to weaken the rebels until reinforcements arrived to assist them in crushing the insurrection. The clever rebel leader pretended to retreat but turned around suddenly and attacked the Franks. The Saxons prevailed in what was likely a bloody encounter. Charlemagne, who had reached Auxerre on his way back to the Rhine region, dispatched a large force to Sax- ony with orders to destroy Widukind’s army. Having learned that the Saxons were in the Lahn Valley, the Franks pursued them. They finally overtook the Saxons near Leisa and overpowered them. Widukind led the remnants of his force north to Wigmodia, the region that lay between the lower Weser and Elbe Rivers. He established a base for future operations in Wigmodia where he could receive assistance from the Danes and several tribes of pagan Slavs that lived east of the Elbe.

Charlemagne gathered a new army at Duren on the west side of the Rhine in the spring of 779. The Carolingian army marched north along the west bank of the Rhine and then crossed the wide river to attack the Westphalian settlement at Bocholt. The Saxons cowered before the Carolingian host, according to the Annalist. “The Saxons wanted to put up resis- tance at Bocholt,” he wrote. “With the help of God they did not prevail but fled, abandoning every one of their bulwarks.”

With the Frankish sword at their throat, the Westphalian nobles, with the exception of Widukind who once again had fled to safety with the Danes, all swore their loyalty to Charlemagne. The Carolingian king then turned south to the Lippe Valley. He led his Frankish host east along the Westphalian Hellweg to the East- phalian town of Medofulli where he compelled the Angrians and Eastphalians to submit to him.

The following year, Charlemagne marched with a sizable force to the Eastphalian settlement of Orhum. He once again demanded that the Saxons swear their loyalty to him, which they traditionally did by swearing on their weapons, and hand over additional hostages as a way to guarantee their compliance. He also continued with the work of dividing Saxony into ecclesiastical units with bishops overseeing the monumental task of converting the pagan Saxons to Christianity.

Two years passed by without a major Saxon revolt. The Frankish fortresses in southern Saxony and northern Hesse had substantial garrisons, and this likely discouraged large-scale Saxon raids against Frankish towns and settlements. In the spring of 782, Charlemagne held his annual assembly at the Lippespringe, which was the source of the Lippe River. He ordered the Saxon nobility to attend, and he informed them that he planned to divide Saxony into Frankish counties and that they would be ruled by Saxon counts who had converted to Chris- tianity. At the same time, Charlemagne’s royal advisers working with church officials issued a harsh set of rules known as the “First Saxon Capitulary.” The document outlawed pagan worship and contained a comprehensive set of rules regarding Christian worship to which the Saxons were to adhere. Of the 34 clauses contained in the capitulary, violation of any one of 14 of them was punishable by death.

Once these matters had been addressed, Charlemagne departed for the Duchy of Bavaria where he went to work planning the conquest of the Avar Khanate that lay east of the duchy. While in Bavaria, he was informed during the summer that the Slav Sorbs were conducting raids against Saxony and Thuringia. He therefore ordered three of his ministers to assemble a Frankish scara, which was to be supplemented with Saxon auxiliaries. A scara was a picked group of strong warriors, according to the 7th-century Chronicle of Fredegar. Depending on the scope of the campaign, scarae might be recruited locally or, in the case of a large cam- paign, from multiple regions. The scara mobilized for the 782 expedition was to punish the Slav Sorbs for their transgressions and consisted of light and heavy cavalry, but no foot soldiers, and was supplemented with mounted Saxon auxiliaries. The nobles, each of whom belonged to Charlemagne’s court, were Chamberlain Adalgis, Count of the Stables Gallo, and Count of the Palace Worad. Of the three ministers, Adalgis was the senior commander.

Charlemagne built upon the Carolingian system for military recruitment of free men by estab- lishing a quota tied to wealth. A free man’s wealth determined the minimum amount of equipment he should furnish when answering the call to participate in an expedition. A free man who owned 12 manses (the equivalent of approximately 300 to 500 acres) was required to outfit himself as a heavy cavalryman. Those who owned fewer than 12 manses were required to equip themselves as light cavalry. Nobles with large estates were required to furnish a specified number of cavalry or foot soldiers in relation to their wealth.

The Frankish heavy cavalry was superior to any troops on the eastern frontier that might be encountered in the open field, including Saxons, Slavs, Avars, Frisians, and Danes. The Frankish heavy cavalryman wore a helmet and mail coat and carried a shield with a boss. He carried a spear and a double-edged long sword between 35 to 39 inches in length. As for the Frankish foot sol- diers, their primary weapon was the heavy spear, which was used for thrusting. They also carried a shield and a bow with a dozen arrows.

The three commanders of the Carolingian expedition against the Slav Sorbs departed in late summer from Koblenz. Rather than take the Westphalian Hellweg, Adalgis led them through Hesse and Thuringia. They were operating east of the Thuringian-Sorbian border when they learned that the Saxons had risen up in revolt and were murdering Christian priests and monks.

Aware that Charlemagne was campaigning in Bavaria, Widukind returned to Saxony from Denmark. He crossed the Aller River at Verden and established a fortified camp on a northern spur of the Suntel Mountains known as the Hohenstein, which overlooked the Weser River. The Suntel Mountains are not characterized by sharp peaks; instead, their tops are gently rounded and some spurs are crowned by plateaus. Widukind had a keen eye for terrain, and he had chosen his ground carefully. Surrounded on three sides by cliffs, the Saxons awaited a Frankish attack from the southeast, which offered the only approach over level ground available to a mounted force of attackers.

While the Saxons toiled to enhance their field fortifications, Aldagis and his co-commanders backtracked to Hesse and turned north to Eresburg where they rendezvoused with Count Theodoric, a trusted cousin of Charlemagne, who had led a large scara of foot soldiers into Saxony to reinforce the scara under the three Carolingian officials.

After a brief meeting, the four Frankish commanders agreed to conduct a pincer attack. That approach, however, would only be viable if the terrain allowed it. If Widukind had his troops deployed with their backs to the Suntel Mountains, it might not be possible to get behind them. Therefore, Theodoric suggested that the nobles conduct a thorough reconnaissance of the Saxon position before launching their attack. Theodoric seemed to be acting like the principal leader of the combined army, and Adalgis and the other two commanders feared that he would try to steal their glory after they had crushed the rebels.

The Carolingian troops set off together to engage Widukind’s rebel army, which continued to grow in size as Saxons flocked to his side from the north and east, which were areas not yet pacified by the Franks. The Carolingians marched east through the Diemal Valley and then turned north to continue their advance along the Weser River. The cavalry under the trio of senior commanders formed the vanguard, and the foot soldiers under Theodoric constituted the main body. The exact size of the combined Carolingian forces is unknown, but it was smaller than the Saxon army that it was marching to destroy. A large Carolingian army of the time might have 15,000 men, but that was the size of an army Charlemagne might lead on a major campaign. The army that marched to crush Widukind probably numbered 3,000 men. As for Widukind, he commanded approximately 4,500 men.

When the Carolingian army was opposite the Suntel Hills to the northeast, Adalgis led the vanguard across the Weser at a suitable crossing point. North of the Lippe River the terrain changed dramatically, becoming more rugged on both sides of the Weser River. The land on the right bank of the Weser belonged to the Angrians, and they knew every track and trail. The vanguard proceeded with a sense of urgency, knowing that it was operating in rebel-infested terrain to the east side of the mountains. At that point, the Carolingian cavalry entered thick woods that blotted out the sun and ascended to the top of the 1,500-foot ridgeline where it bivouacked in the vicinity of the Hohe Egge, which was the highest point in the Suntel Mountains. At that point, the Carolin- gian vanguard was only two miles from Widukind’s fortified encampment on the Hohenstein.

Once the vanguard had crossed to the east bank of the Weser, Theodoric led the main body downstream. The foot soldiers plunged through a ford of the Weser and established a camp on the right bank astride a principal track that led west into Westphalia. He purposely chose that location so that if the Saxons tried to raid westward, he would be in a good location to disrupt their advance. While he waited for word from the commanders of the vanguard, Theodoric set his men to work fortifying their position in case they were attacked by the rebels.

At their mountain camp, the three commanders of the Frankish vanguard conferred as to their next step. The trio of veteran commanders assumed that they would have no trouble over- running the Saxons. For that reason, they con- spired to smash the rebels without coordinating their movement with Theodoric. They believed “that if they had Theodoric with them in the battle the renown of the victory would be transferred to his name, and they therefore resolved to engage the Saxons without him,” wrote the Annalist. Believing that a reconnaissance would only serve to alert the Saxons of their approach, they decided to forego a fundamental part of any offensive action.

But Adalgis and his co-commanders deeply underestimated their foe. Believing that the Frankish horsemen would not attack a fortified position alone without the assistance of a sizable force of foot soldiers, Widukind led his foot soldiers outside the fort. They deployed in line of battle with the palisade directly behind them. By making his army seem vulnerable, Widukind hoped to lure the Frankish cavalry into a pre- mature attack before it could be reinforced with foot soldiers.

The day of the battle, the Franks in the vanguard mounted their horses and rode as quickly as possible along the ridgeline. Their mood was one of unbounded confidence, according to the Annalist. “They took up their arms and, as if they were chasing runaways rather and gather- ingbootyinsteadof facinganenemylinedup for battle,” he wrote. “Everybody dashed as fast as his horse would carry him for the place out- side the Saxon camp, where the Saxons were standing in battle array.”

Although details are almost nonexistent for the battle that unfolded at the Saxons’ camp, modern historians offer a likely scenario based on similar encounters and knowledge of Saxon tactics. Widukind ordered archers and men armed with javelins into the woods along the track leading to the Hohenstein encampment. The Saxon archers, javelin throwers, and slingers were light foot soldiers who had neither helmets nor mail and therefore could not engage a Frankish warrior in hand-to-hand combat with any hope of success. Their job was simply to try to inflict injury with their missile fire. The commanders of the ambush teams allowed the Franks to get well into the kill zone before giving the order to fire. From their hiding positions behind trees, the bowman killed some of the Frankish horsemen, but since the Franks wore helmets and mail, many of the riders avoided serious injury during the ambush.

The Carolingian heavy cavalry rode as fast as possible through the ambush. When they neared the Saxons’ encampment, the Franks saw a line of Saxon spearmen deployed in front of their palisade with archers on a rampart inside the field fort. The Saxon archers fired over the heads of the spearmen in an effort to inflict more casualties on the Franks as they prepared to charge. At that point, Widukind’s heavy foot soldiers, who stood shoulder to shoulder, planted their spears at an angle to foil the cavalry charge. They wore helmets and carried large round shields, which they positioned in an overlapping manner for increased protection.

Adalgis was in the center of the line with Gallo and Worad commanding warriors on Adalgis’ right and left, respectively. Because of the rugged nature of the terrain and their hasty attack, the Franks struck the Saxon line in a piecemeal fashion. The Saxons killed the Franks’ horses to prevent their escape. The Sax- ons stabbed the Franks with their spears and hacked at them with swords and battle axes. As Frankish casualties mounted, the remaining Franks fled into the surrounding ravines pursued by the victorious Saxons.

The Annalist exaggerates somewhat by stating that all of the Franks were slain, but he is correct in his assessment that the Franks never had the upper hand. “The battle was as bad as the approach,” he wrote. “As soon as the fight- ing began, they were surrounded by the Saxons and slain almost to a man.”

Aldagis and Gallo made a last stand in the Blutbach (Blood Stream) in a valley on the north side of the Hohenstein. They fought to the death against overwhelming Saxon numbers. As for Worad, he and a small group of men managed to successfully fight their way out to the south. To reach Theodoric’s camp, they scrambled over the mountain and made their way toward the Weser. When Theodoric learned of the disaster, he ordered a general withdrawal to Eresburg. Although the exact losses are unknown, the Carolingian mounted vanguard lost two of its three commanders, four counts, and 20 other high-ranking nobles, according to the Annalist.

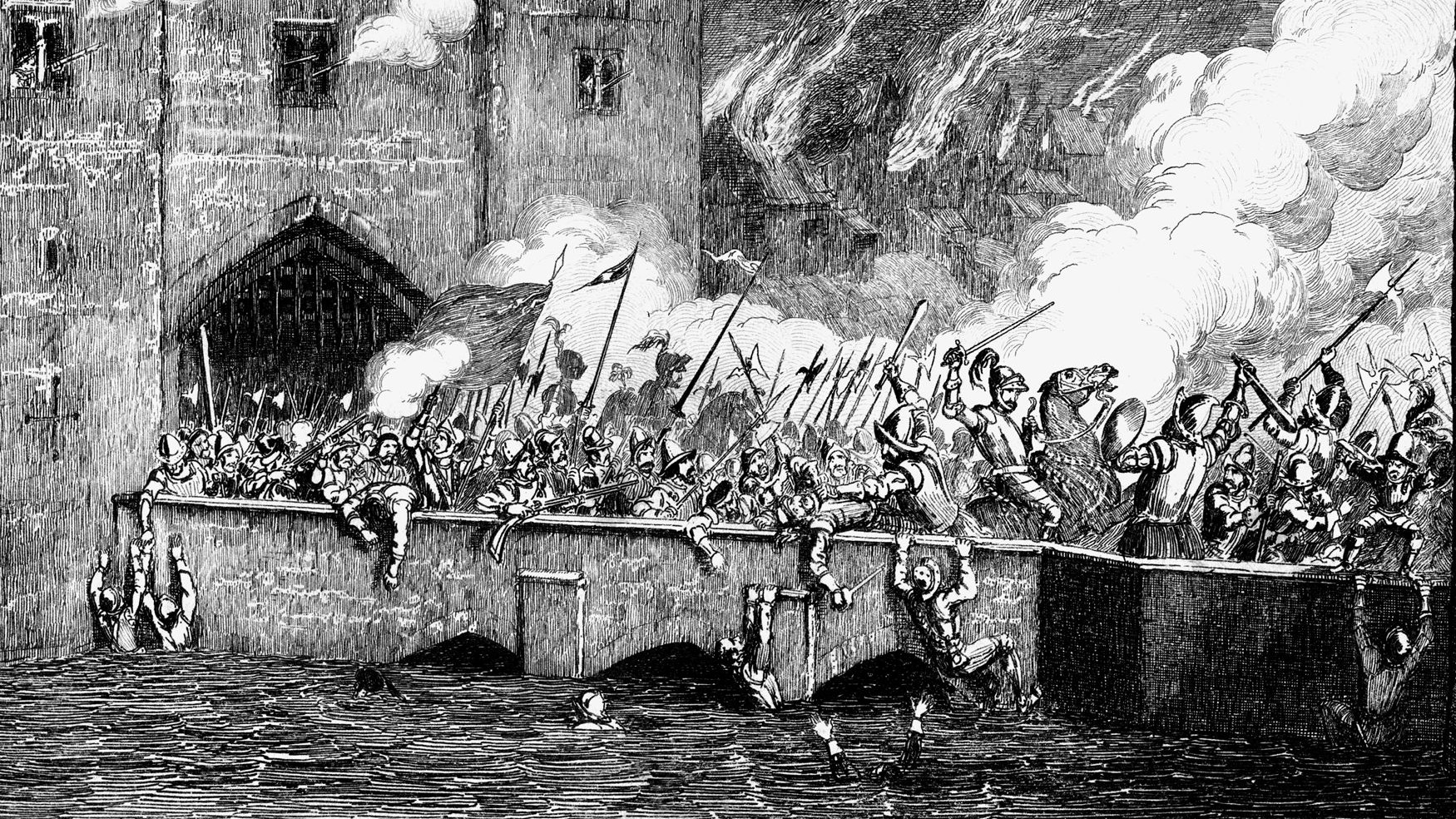

Upon learning of the humiliating defeat in the Suntel Mountains, Charlemagne departed Bavaria for Saxony. He led a large Carolingian army from Bavaria to Eresburg. Sensing retri- bution at hand, Widukind once again sought safe haven with the Danes, thus leaving his hapless rebels to their fate. The Carolingian king summoned the Saxons who had destroyed the Frankish army in the Suntel Mountains to appear before him to receive their punishment. The Saxons who had participated in the rebellion were ordered to assemble at the Saxon settlement of Verden on the Aller River and await Charlemagne’s arrival. Since they probably believed Charlemagne would hunt them down if they failed to appear, the cowed Saxons assembled at Verden as instructed. Aware that his reputation throughout Europe was at stake following the debacle, Charlemagne unmercifully ordered the immediate execution of 4,500 Saxons who answered the summons. The tyranny that Charlemagne displayed at Verden was regarded by many Franks as unconscionable.

Despite Charlemagne’s decision to execute the rebels, the Saxon rebellion flared up anew the following year. Widukind returned to Saxony to lead the rebellion. To gain the upper hand, Charle- magne recruited additional forces, which he fed into the main theater of the war between the Hase River in Westphalia and the Elbe River in Eastphalia. The Carolingian troops used Paderborn and several nearby fortresses as their base from which to conduct strikes against the Saxon rebels. Once the Carolingian forces had gained the upper hand, Charlemagne led a fast-moving mounted column on a lengthy raid that began in Westphalia and went as far east as the Elbe River. Once his column reached the Elbe, Charlemagne turned south into friendly territory in Thuringia. Afterward, the Franks disbanded for the year, and Charlemagne returned to Austrasia.

In 784, Charlemagne once again marched into Saxony. He divided his army in half to form two smaller armies. He gave command of one army to his son, Charles the Younger, with instructions to suppress the Westphalians, and he took command of the other army. Charle- magne led his army on a long raid through Eastphalia during which the Franks burned Saxon villages and destroyed their crops. Widukind stayed in Saxony to fight the Franks, but as always he remained elusive. In the late spring of 785, Charlemagne held his annual assembly at Paderborn during which he met with both Frankish and Saxon nobles. From Paderborn, Charlemagne “marched through all of Saxony wherever he wished, on open roads with nobody putting up any resistance,” wrote the Annalist.

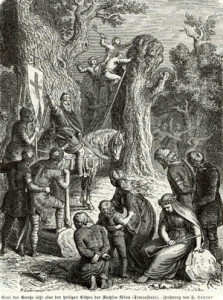

Later that year, Widukind signaled his willingness to negotiate with Charlemagne provided the Carolingian ruler guaranteed his safety. Charlemagne agreed, and Widukind travelled under escort to Attigny in Austrasia where he and other recalcitrant Saxon leaders were baptized on Christmas Day 785. Although this was a significant milestone in the suppression of the Saxons, further uprisings would occur intermittently for nearly two more decades until they finally stopped in 804. During that time, Charlemagne ordered the resettlement of many of the Sax- ons into the interior of the Carolingian realm. “He took ten thousand of the inhabitants of both banks of the Elbe, with their wives and children, and planted them in many groups in various parts of Germany and Gaul,” wrote Einhard.

Through his conquest of Saxony, Charlemagne proved that he had nearly superhuman stamina and an iron will. Although faced with constant setbacks, he kept his eye on the goal of integrating the Saxons into the Carolingian realm, and he eventually achieved that objective.

remember, this was written by the winner so this is his opinion.

The author cites a painting of Widukind being baptized. Which one is he? The one in the center bowing with his sword, a helmet on? Or the in at far right end with wearing white sheets?