By Jon Diamond

After the carrier attack by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, Japanese forces conducted offensive operations across an incredibly broad front of 7,000 miles from Singapore to Midway Island. The success of Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s aerial assault on the anchorage of the United States Navy’s Pacific Fleet that fateful morning assured the Japanese complete naval supremacy in the Pacific Ocean.

During early war-planning sessions in Tokyo, Malaya and Singapore were targets for the Imperial Japanese Army’s (IJA) major thrusts while additional supporting operations were mounted to seize the Philippines, Guam, Hong Kong, and parts of British Borneo in the Western Pacific. Guam was occupied easily by December 8, 1941, and Wake Island fell on December 23 after a spirited fight from its U.S. Marine Defense Battalion.

The Japanese high command had planned that once Malaya and Singapore were captured these British bastions would serve as a springboard to seize southern Sumatra and launch an invasion of the Netherlands East Indies with its vast resources to supply Japan and its war effort, which had been occurring on the Asian mainland for almost a decade. Adding to the Japanese hegemony over the Pacific Ocean was the sinking in the South China Sea of the battleship HMS Prince of Wales and battlecruiser HMS Repulse, dispatched by Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill to serve as a deterrent to Japanese expansion, on December 10, 1941, by land-based Mitsubishi G4M Betty and G3M Nell medium horizontal and torpedo bombers.

Malaya and Singapore fell to a numerically inferior Japanese 25th Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita, on February 15, 1942 after only 70 days of resistance to the Japanese juggernaut down the Malay Peninsula and across the Straits of Johore to Singapore Island.

Australia had sent two brigades of its 8th Division to Malaya. This 15,000-man contingent, after considerable fighting toward the end of the campaign, was forced to surrender in mid-February with the rest of Singapore’s garrison. The three remaining battalions of the Australian Imperial Force’s (AIF) 8th Division were sent to reinforce the Dutch at Amboina and Timor in the Netherlands East Indies, as well as Rabaul on the northern tip of New Britain in the Bismarck Archipelago, which was administered by Australia.

Before the fall of Singapore, Japanese units started their conquest of the Netherlands East Indies despite the fact that the local Dutch government had more than 100,000 men available. Unfortunately, this large force was spread out piecemeal across the major islands of the Indonesian archipelago. The American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) forces were quickly routed on the ground and in the skies and dispatched in the Battle of the Java Sea. Tarakan Island fell on January 10, 1942, followed by the capture of Borneo and Sumatra. Java ended its resistance on March 8. After the loss of the Netherlands East Indies, American General George Brett, who had been British General Archibald Wavell’s chief American deputy in the ABDA command, was appointed commander of all U.S. forces in Australia until General Douglas MacArthur arrived at the behest of President Franklin Roosevelt and Prime Minister John Curtin of Australia. At this juncture, most of this force was composed of air units that landed in Australia after fleeing the Philippines and East Indies.

Also, prior to the collapse of Malaya, the first Japanese air attack against Rabaul occurred on January 21, 1942, with more than 100 Japanese fighters and bombers attacking the main Australian air base in the Bismarck Archipelago, northeast of New Guinea. Eight of 10 RAAF Wirraway fighters, which were basically American AT-6 (Texan) trainers, and three Lockheed Hudson bombers were destroyed. On the night of January 22, Maj. Gen. Tomitaro Horii’s 5,300-strong South Seas Detachment steamed into Rabaul Harbor. The 1,400 Australian defenders put up a brave fight but eventually withdrew. As the Japanese overran the northern part of New Britain in the ensuing days, most of the Australians were brutally massacred or died as prisoners.

The RAAF chief at Rabaul evacuated the remainder of his air detachment, two surviving Wirraways and one Lockheed Hudson, back to Australia. Now all that separated Australia from the Japanese offensive were a few Australian troops in the Bulolo Valley near Wau, southeast of Salamaua on the Huon Gulf in northeast New Guinea, and the small garrison at Port Moresby on the southern coast of Papua. After seizing Rabaul, the Japanese became interested in occupying both of these areas. Japanese staging moves to take Papua began on March 8-11, 1942, when IJA and Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) elements landed at Salamaua, Lae, and Finschhafen on the Huon Gulf. From April 1-20, Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF) troops landed at Fafak, Babo, Sorong, Manokwari, Momi, Nabire, Seroi, Sarmi, and Hollandia along the north coast of New Guinea.

New Guinea is the second largest island in the world, located immediately north of the Australian continent. It is 1,500 miles long, and Australia’s military planners regarded it as a buffer against Japanese invasion of its Northern Territories. The southeastern part of New Guinea, Papua, which occupies one-third of the total area, was administered by Australia. Papua’s interior is inhospitable. The Owen Stanley Mountains dominate the topography, and the area is replete with jungles and swamps.

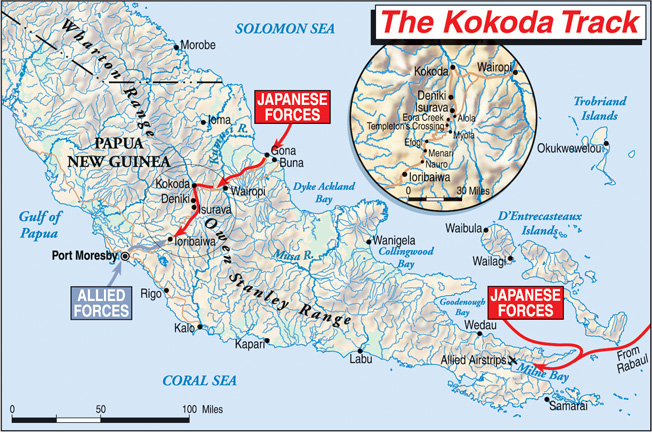

Although New Guinea possessed no cities or towns with the exception of the smaller ones at Port Moresby, Milne Bay, Lae, and Finschhafen, Papua had numerous small villages inhabited by roughly 100,000 native Melanesians of differing tribal origin. The main town was Port Moresby on the south coast with a population of 3,000 before the war. The name Papua emanates from a Dutch word meaning “fuzzy,” a reference to the bushy hair of the Melanesian populace. In the almost 400 years of Portuguese, Dutch, British, German, and Australian colonial involvement on New Guinea, all that existed were a few coconut plantations, trading posts, and small Christian missions, such as at the villages of Buna and Gona on the northeastern coast. Away from Port Moresby, only native paths connected the northern and southern Papuan coasts. The most famous was the Kokoda Trail, named after a village on that mountainous, muddy track. Much of the Kokoda Trail spanned high hills that rose into the clouds cordoned by forests thick with undergrowth. Torrential tropical rains fell so extensively that they filled the ravines and gullies with fast-flowing streams that impeded infantry movement.

The village of Kokoda lay in a valley 1,200 feet above sea level on the northern foothills of the Owen Stanley Range. In addition to having a Papuan Administration post and a rubber plantation, Kokoda also had a small airfield that was a main objective in the Japanese advance from Papua’s northern coast. Toward the end of July 1942, Lt. Gen. Harukichi Hyakutake, the IJA 17th Army commander, had landed some 13,500 troops at Buna and Gona and forced the Australians, mainly militia, back beyond Kokoda to a ridge position at Deniki. The fighting was mostly guerrilla-style with firefights and ambushes in both wet jungle and tall Kunai grasslands. There was no possibility of taking any vehicle along the track since it was only a few feet wide and could only be traversed through its ridges, valley, jungles, and streams by foot-slogging marches through calf-high mud.

Rabaul would become the headquarters for the Japanese 8th Area Army and would also have five airfields and a harbor that could serve as an anchorage for a large part of the IJN. Across the Arafura Sea from Papua lay the arid Northern Territories of the Australian continent. After their amazing string of lightning successes, the Japanese were presented with a military decision borne from their rapid conquests; namely, should there be a further expansion into the South Pacific to cut the long supply lines from the United States to Australia and New Zealand? However, the IJA decided to move southward in mid-January, first to New Britain with Rabaul’s seizure and from there to occupy key positions in Papua, notably the town of Port Moresby on the southern coast. By so doing, the Japanese high command left the South Pacific supply routes open to Australia and New Zealand, an omission it would later regret. Eventually, the Japanese decided that the establishment of further bases at New Caledonia, Fiji, the Solomon Islands, and Samoa would isolate Australia and allow better defense of the southern rim of the Pacific.

Darwin, an administrative seat in the Northwest Territories of Australia, was now under direct threat from the advancing Japanese. Darwin was also a terminus for European air routes to Australia and a major seaport in the north. The Australian government, with most of its army in the Middle East, could only spare modest reinforcements for Darwin’s garrison of 14,000 men and a couple of Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) squadrons stationed there. At the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, 121,000 Australian soldiers were serving overseas, leaving only 37,000 to defend Australia. The RAAF had suffered grievously in Malaya and Singapore, losing 165 planes, thus leaving only 175 for Australia’s defense. Aside from Consolidated PBY Catalina patrol bombers and 53 Lockheed Hudson bombers, the majority of planes of the RAAF were Wirraways. The Japanese bombed Darwin on February 19, 1942, for the first time from aircraft carriers and from the Kendari base in the Celebes.

The Japanese were establishing bases along the northern coast of northeastern New Guinea and Papua. They had for the time being abandoned any idea of invading Australia directly, partially due to their major troop commitment to China and Manchuria, and instead planned to isolate the Northern Territories, including Darwin and its harbor, by occupying Port Moresby.

Thus, the town of Port Moresby became Japan’s prime strategic objective in the spring of 1942. Initially, rather than taking Port Moresby by an overland route, the IJN was to capture it in an amphibious operation, which was mitigated by a U.S. carrier task force at the Battle of the Coral Sea on May 4-8, 1942. Despite the loss of the aircraft carrier USS Lexington and damage to the carrier USS Yorktown, the U.S. Navy compelled the Japanese invasion force to retreat after losing a carrier and having another one damaged. Additionally, many experienced IJN pilots died in the sea battle, the first fought solely by carrier-based planes.

The surrender of Singapore, with a large contingent of the Australian 8th Division, upset Australia’s prewar defense planning. Prime Minister John Curtin wanted his divisions in the Middle East to return home for the defense of Australia. Two brigades of the 6th Division were temporarily transferred to Ceylon, while the division’s remaining brigade and the 7th Division would be returned to Australia with its leading elements arriving in mid-March 1942. With the 9th Division remaining in the Middle East, Curtin was mollified with the green American 32nd and 41st Infantry Divisions being hastily deployed to Australia’s defense. The 41st Division arrived in Australia in April 1942 and the 32nd in May.

In early March 1942, Port Moresby had only the 30th Infantry Brigade, a field artillery regiment, and coastal and antiaircraft units, totaling between 6,000 and 7,000 men, for defense. On February 21, President Franklin Roosevelt cabled General Douglas MacArthur on Corregidor and ordered him to leave the besieged island in the Philippines and proceed to Australia. He arrived at Batchelor Field, south of Darwin, on March 17.

Neither the Allies nor the Japanese were prepared for a major war in the South Pacific, which was not only remote but also disease ridden and ubiquitously wet. The Australians, many of whom had experience in the North African desert, Greece, Crete, and Syria, had not had any training for the upland jungle they found in several parts of Papua. In order for the combatants to advance in New Guinea, they would need to be able to construct improvised bridges and roads. Because of the extensive coastline of the northern Papuan coast near Buna, troops of the American 32nd Division sailed there on a motley collection of coastal craft and wooden schooners.

As an Allied land forces commander, Prime Minister Curtin selected General Sir Thomas Blamey. MacArthur and his staff derided Blamey, although he had served gallantly in World War I. After as stint as police chief in Melbourne, he served in North Africa and the Levant. Maj. Gen. and Deputy Chief of the Australian General Staff George A. Vasey lambasted MacArthur’s headquarters in Brisbane as being “like a bloody barometer in a cyclone-up and down every two minutes.”

Lieutenant General Sydney F. Rowell was the commander of New Guinea Force comprising the crack Australian 7th Division, veterans of the Middle East, two of its brigades going to Port Moresby while its third, the 18th, was dispatched to Milne Bay. After displeasing MacArthur, primarily due to the continued withdrawal of his Australian forces on the Kokoda Trail, Blamey was forced to relieve Rowell of his command of New Guinea Force.

After the Battle of Midway in June 1942, Lt. Gen. Harukichi Hyakutake’s 17th Army was ordered to gather its divisions in the Philippines, Java, and Rabaul and prepare for the attack on Port Moresby. The Japanese decided to bypass New Caledonia, Fiji, and Samoa and to make a two-pronged approach on Port Moresby; one route would be along the coast from Milne Bay, which would be taken in an assault from the sea, while the other route would be overland from Buna and Gona along the rugged Kokoda Trail.

Milne Bay and Buna were coveted as future bases by both the Japanese and the Allied war planners in the Southwest Pacific. The Japanese beat the Allies to Buna and Gona; however, the Allies were more fortunate at Milne Bay, on the southeast end of Papua, getting there first in July 1942 with the Australian Militia 7th Brigade and a force of U.S. engineers to occupy the northern and western coastline, establish defensive positions, and begin constructing an airfield to accommodate two RAAF Kittyhawk fighter squadrons and a few Hudson reconnaissance bombers. The airfield was completed by August 1942.

The airstrip had been constructed by the 43rd U.S. Engineer Regiment and 24th Field Company of the Australian Militia. Second and third airstrips were being cleared of coconut trees and defensive positions prepared. Milne Bay was 20 miles long from east to west. On the western shore of the bay was a large coconut plantation, Gili Gili, surrounded heavily wooded hills. A track that winding the entire way around the bay was usually muddy and closed in by nearby mangrove swamps on both the seaward and northern sides.

The Japanese conducted an amphibious offensive in late August 1942, using the IJN’s 8th Fleet and a landing force to seize Milne Bay’s airfields and base to support the ongoing overland Port Moresby assault and concurrent Guadalcanal operation. The Japanese force that attacked Milne Bay had lost some of its offensive strength when one of its regiments was transferred to Guadalcanal. The 2,000-man Hayashi Force (1st Landing Force), launched from New Ireland, landed on the bay’s northern shore on the night of August 25 against a strong Allied defense. The Japanese were under the faulty impression that there were only two or three companies of Australian infantry to defend the airfield. A second landing force with a naval labor corps arrived at Milne Bay on the morning of August 26. At Milne Bay, the Japanese owned the sea since the U.S. and Royal Australian Navies were heavily engaged off Guadalcanal. However, ashore there were two Australian infantry brigades at Milne Bay comprised of the veteran 18th Brigade under Brigadier George F. Wooten, who led the same three battalions (2/9th, 2/10th, 2/12th) of his brigade in Libya, and the Australian Militia’s 7th Brigade, under Brigadier Field, comprising Queenslanders of the 9th, 25th, and 61st battalions. The whole of Milne Force, as the collective brigades had been named, was controlled by Maj. Gen. Cyril Clowes and numbered about 4,500 infantry. In addition, there was a 25-pounder battery of the 2/5th Field Regiment. Clowes was a regular soldier who had served as an artilleryman and led the Anzac Corps artillery in Greece in 1940. Without naval forces, coastal guns, or searchlights, Clowes awaited the Japanese landings after he had received reports of transports moving along the eastern Papuan coast.

The initial Japanese landing was made against the Australian 61st (Militia) Battalion, 7th Infantry Brigade, spread out in company strength at Ahioma at the eastern end of Milne Bay, early on August 26. As more Japanese troops landed, the Australians withdrew along the northern shore’s track, faster when they saw an enemy tank crawling along. The Japanese had landed some light and medium tanks, and the Australian defenders lacked effective anti-tank weaponry. The RAAF Kittyhawk and Hudson pilots attacked the enemy landing points and destroyed stores and fuel supplies on the beaches as well as stranding seven Japanese landing barges that had to be beached on nearby Goodenough Island. The transport Nankai Maru was sunk with several hundred Japanese infantrymen aboard. A Hudson’s bomb hit forced a Japanese destroyer to return to its base. The Japanese used their patented tactics of encirclement and night assaults in an attempt to confuse and divide the Australians. The 2/10th Battalion of the veteran Australian 18th Infantry Brigade moved up to help the beleaguered 61st Battalion and took the brunt of the ensuing Japanese advance westward to the KB Mission on August 27. The Queensland militia battalions, in their initial combat, had shown the North African combat-hardened formations that they, too, could fight like veterans. As the Japanese advanced on the track along the northern coast of Milne Bay, Clowes sensed the danger but held onto his reserve battalions, maintaining a narrow base perimeter with the rear clear in case he needed to move back into the hills to the north of the bay and the airfields. However, the 25th (Militia) Battalion, 7th Infantry Brigade moved up along the northern coast road to Rabi with an antitank gun, some sticky bombs, and Molotov cocktails on the night of the August 27.

On the 28th, the Australian defenses were forming near the cleared but unused Number 3 airstrip, northeast of Gili Gili, the target for a prolonged three-day series of Japanese frontal assaults that had been massing in the surrounding jungles. During the night of August 3, Clowes sent 2/12th Battalion of the 18th Infantry Brigade to support the 61st Battalion already positioned on Strip Number 3. This day marked Clowes’ start of a counteroffensive, which was characterized by a steady series of skirmishes that forced the Japanese to yield territory as they retreated to the east.

On September 5, the 2/9th Battalion, 18th Infantry Brigade attacked behind an artillery barrage supported by RAAF Kittyhawk strafing sorties and pushed the Japanese back until they were forced to give up their main supply base. Clowes was anticipating another Japanese landing on the night of September 6, since Japanese destroyers once again entered Milne Bay; however, their mission was to pick up the surviving infantrymen after their defeated amphibious assault, not to land reinforcements. On the morning of September 7, a cruiser and two corvettes extracted about 600 soldiers, the last of the invasion force. Previously, 350 Japanese were left stranded on Goodenough Island, another 300 drowned when their transport was sunk, and 700 died in the fighting along Milne Bay’s northern shore track.

At the conclusion of the fighting at Milne Bay, with the Japanese evacuating under naval cover on September 6th, General William Slim of Indian Army fame wrote of the Milne Bay defenders, “It was Australian soldiers who first broke the spell of the invincibility of the Japanese Army.” It pleased the Australian General Staff, despite MacArthur’s condescension, that their militia was able to stand up to several determined Japanese attacks.

After the repulse of the amphibious assault on Port Moresby at the Battle of the Coral Sea, an overland campaign was launched on July 21 when Japanese cruisers, destroyers, and transports landed infantry and engineers of the Yokoyama Advance Force at Buna and Gona on Papua’s north coast.

With an airfield at Buna, the Japanese thought that they could go overland to seize Port Moresby. After the Japanese occupied Buna, they next pushed down the Kokoda Trail, over the Owen Stanley Mountains, toward Port Moresby. The trail was a 145-mile mud path that crossed some of the most inhospitable terrain in the world.

Thus began the brutal confrontation for the Kokoda Trail, lasting well into October 1942, which committed the remainder of the Japanese 144th Infantry Regiment, the South Seas Detachment HQ (Horii Detachment, 4,400 troops, which had captured Rabaul), elements of the 41st Infantry Regiment (2,100 troops) under Colonel Yazawa Kiyomi, two artillery regiments, and service troops added to the reconnaissance force, led by engineer officer Colonel Yokoyama, that had landed there in late July. General Horii had a well-balanced total fighting force of about 10,000 troops built around a nucleus of the 144th and 41st Infantry Regiments, battle-hardened veterans of campaigns in China, the Philippines, and Malaya.

The Allies had wanted Australian troops with the American I Corps, the 32nd and 41st Divisions under Lt. Gen. Robert Eichelberger, to secure the crest of the Owen Stanley Range from Kokoda northwest to Wau and then advance all the way to the Buna-Gona area. However, with the Japanese coming south down the Kokoda Trail from Buna in force, the Australian 39th Militia Battalion, led by Brigadier Porter, was hurriedly sent to block the advance from Papua’s northern coast to Kokoda Village. However, they were too few in number to hold the Japanese back, and the enemy was gaining ground in its drive against the Australian militia.

Yokoyama’s engineer group met the Australian militiamen and quickly drove them off with their superior infantry tactics. The understrength 39th Battalion sent out small patrols, set up ambushes, and functioned as skirmishers. Despite a large number of casualties, the Japanese inexorably pushed southward, forcing the Australians back. By the end of July, after only seven days of fighting, Kokoda Village and its airfield were in Japanese hands. Japanese 17th Army headquarters ordered Horii to attack along the old native trail with his larger force. Kokoda Village became a Japanese supply base as more troops were in transit from Rabaul for the overland attack.

The Australian efforts to delay the Japanese were intensified when the 53rd Battalion, under Lt. Col. Honner, moved up to assist the 39th Battalion, a spent force after three weeks of combat. By August 16, the 21st Brigade, 7th Division, under Maj. Gen. Arthur “Tubby” Allen, who had commanded a brigade in North Africa, Greece, and the Levant, arrived on the Kokoda Trail with its 2/14th Battalion starting the ascent up the “Golden Stairs” from Uberi. The Golden Stairs consisted of steps varying from 10 to 18 inches in height with the front edge of the step being a small log held in place by stakes. The Australian militiamen and regulars often carried sticks to support their weight as they ascended this exhausting trail. Native Papuan bearers provided much needed assistance transporting supplies and carrying wounded back down the trail toward Port Moresby.

On August 26, the Japanese launched a general offensive to take Port Moresby. The Australian Militia 39th and 53rd Battalions stood between them and Isurava and Alola. As the 21st Brigade, 7th Division came into the line, the Japanese attacks stiffened, and the fighting became more continuous. Machine-gun nests, sniping, and booby traps became the tactics of choice. The weight of the Japanese offensive continued, and the Australians fell back roughly 15 miles to Efogi. On September 1, General Horii’s offensive received an additional 1,000 fresh reinforcements that had landed on the Papuan northern coast, which he intended to send to his 144th Infantry Regiment. Horii now had roughly a force of two complete infantry brigades along with service troops and engineers and two mountain guns.

As the Japanese engaged the seasoned 21st Brigade, now including the 2/16th Battalion, their casualties began to mount. Malnutrition, infected leg sores, and tropical diseases were culling the Japanese ranks. Yet, the Australians were forced to retreat, and the Japanese were driven by their officers to keep up pressure on their flanks. The Japanese were positioned along the ridge at Ioribaiwa, and the Australian infantry on the Imita Ridge across the valley from the enemy. Each side stood firm.

Although Horii had 5,000 troops attacking the Australians, Japanese lines of communication had been steadily lengthening from both Buna and Gona, while the Australian communication lines was becoming shorter as they retreated toward Port Moresby. The Ioribaiwa-Imita area was only a few hours’ march, under 10 miles, from Port Moresby, leading Allen and Rowell to believe that at this point, with better communications, they could stop the Japanese movement.

This final defensive position would also become the starting line for the Australian counteroffensive to retake Kokoda Village and continue to Buna and Gona. The fresh Australian 25th Brigade, in its new jungle green kit, arrived at the Ioribaiwa-Imita area, raising the spirits of the Australian defenders, although the Japanese could now vaguely see distant Port Moresby from their positions. At the end of August, however, General Horii was ordered by Imperial General Headquarters to assume defensive positions on the Kokoda Trail as soon as he crossed the main Owen Stanley Range. As the defeat at Milne Bay and setbacks on Guadalcanal registered in the minds of the Imperial General Headquarters, Horii was further instructed to move back to Papua’s northern coast, although the Japanese general was planning to leave a strong rearguard position at Ioribaiwa. By September 19, the Japanese had lost about 1,000 dead and 1,500 wounded. Australian casualties were 314 killed and 367 wounded.

However, after Rowell was sacked by MacArthur for tardiness in defeating the Japanese and replaced by Lt. Gen. Edmund Herring, the Australian counteroffensive (largely devised by Rowell) from the Imita Ridge began on September 26, forcing the Japanese to start their withdrawal up the Kokoda Trail to Buna and Gona. It was the Australian redoubt at Imita Ridge that had stopped Horii’s advance; the Australians had two “short” 25-pounder field artillery pieces specifically designed for the jungle, which they had dragged up the Golden Stairs. However, it was the orders of the Imperial General Staff that made Horii retreat.

The 25th Brigade led the way north from Imita Ridge back to Kokoda Village. On October 12, Brigadier Kenneth Eather’s three battalions of the 25th Brigade attacked the Japanese at Templeton’s Crossing on the northern side of the main ridge of the Owen Stanley Mountains, successfully dislodging them after five days of stubborn resistance. Brigadier John Lloyd’s 16th Brigade (2/1st, 2/2nd, 2/3rd) entered the fray at Eora Creek, the valley below the climb to the Kokoda plateau, where the Japanese held them up for about a week until a flank attack by the 2/3rd ended enemy resistance.

From Eora Creek the Australians fought uphill against a series Japanese positions beyond which were strong main defenses with a long perimeter. These held until the end of October. MacArthur’s hectoring from the rear headquarters showed a complete ignorance of the battlefield conditions and the Australian generals’ distaste for running up a huge butcher’s bill. MacArthur wanted Kokoda recaptured as quickly as possible so that the force could be built up by airlifting men and supplies to its airfield for the future assault on Buna and Gona. No one commented whether MacArthur was aware that it had taken the Japanese 51 days to advance from Kokoda to Ioribaiwa, but the Australians had required only 35 days to recapture the same ground from an enemy that had acquired much more jungle fieldcraft and tactical use of the terrain and was suicidal in defense of its positions.

The outcome of the fighting on the Kokoda Trail was largely determined by logistics and terrain, in addition to the determination of the Australian Army and militia battalions. The Japanese supply system was stretched to its limits, and the enemy offensive had resulted in 80 percent of its manpower killed, wounded, or disabled by disease. General Horii, under orders, withdrew up the Kokoda Trail to reinforce his defensive positions and garrisons at Buna and Gona, the scenes of horrific jungle fighting that would last into January 1943. This was a strategic retreat for the Japanese because of an increasing need to divert reinforcements elsewhere. From the end of September, the IJA was ordered to redirect its efforts to reclaim Guadalcanal from the American 1st Marine Division, which had landed there and at Tulagi on August 7, 1942.

By the end of 1942, the Australian defenders of southeastern Papua had foiled the Japanese attempt to seize Port Moresby by an overland route. After the recapture of Kokoda Village, Allied planners prepared for their next offensive, which would become a three-month bloody onslaught to recover the vital bases and airfields of Buna, an administration center, and Gona an old mission. Buna consisted of an Australian government station called Buna Mission, a small settlement 500 yards away called Buna Village, and an airstrip. Allied headquarters envisioned a general advance to commence on November 16, 1942, with the Australian 7th Division and the U.S. 32nd Division against the Buna-Gona beachhead. The dividing line between the Australian and U.S. troops was to be the Girua River.

As the crisis on the Kokoda Trail passed, General Blamey demanded that the Allied offensive be an Australian operation. Having initially been overwhelmed by the Japanese just weeks before, he reasoned it was the right place for the “Diggers” to win back their fighting reputation. The Australians, with the Americans advancing along the northern New Guinea coast, would expend much blood to take control of both Buna and Gona. By late 1942, the Australian 7th Division, under Maj. Gen. George Vasey, had reached the northern end of the Kokoda Trail. Their arrival had been anticipated by Blamey, who had flown in the 2/10th Battalion, 18th Infantry Brigade from Milne Bay to Wanigela, a village southeast of Buna. There they established a base and began to reconnoiter the Japanese-held areas on Papua’s northern coast.

Lieutenant General Hatazo Adachi, commander of the Japanese 18th Army, with his headquarters at Rabaul, had about 18,000 troops available for Kokoda-Buna-Gona operations including IJA formations, Imperial Japanese Marine units, engineers, and service troops that had either just landed or survived the retreat up the Kokoda Trail, which had claimed the life of General Horii and his staff, who were drowned trying to escape when their rafts capsized going downstream on the fast-flowing Kumusi River to Lae.

The Japanese garrisons consisted of 2,500 men around Buna; 5,000 men on the northern part of the Kokoda Trail leading into Sanananda Point on the coast a few miles northwest of Buna; about 800 men around Gona, 15 miles to the northwest of Buna (including some highly valued jungle fighters from Formosa); and roughly 900 troops at the mouth of the Kumusi River, 10 miles farther along the coast from Gona. At Sanananda and on the road leading to it, the Japanese commanders placed the bulk of their combat effectives together with some engineers and naval construction troops and two mountain gun batteries. Except at Sanananda Point, the Japanese front was never more than a half a mile from the coast, but the perimeter was covered by the most hellish terrain and extraordinarily fanatical and well-armed defenders. Swamps and dense jungle channeled the Allied attackers down a handful of trails, where a Japanese machine gun in a reinforced pillbox could hold off a battalion.

Blamey’s plan for clearing the Japanese was to advance through Kokoda Village with two brigades of the Australian 7th Division and from south of Buna with regiments of the U.S. 32nd Infantry Division. These forces were pressing Japanese defenses near Buna by late November, but the Americans suffered heavy losses, nearly 2,000 men out of their force of 5,000, and had to be reinforced by another of the regiments stationed at Port Moresby.

An Australian report after the capture of Gona recalled just how well the Japanese engineers had prepared the defenses along the eleven-mile front from Gona in the west to Cape Endaiadere east of Buna Mission and Giropa Point. Hundreds of coconut log bunkers were constructed, some reinforced with iron plates, others with iron rails and oil drums filled with sand. In areas that were too wet for trenches and dugouts, bunkers were built seven to eight feet above the surface and then concealed with earth, tree fronds, and other vegetation. The bunkers, which contained from three to five machine guns, provided interlocking fields of fire. The bunkers were protected by infantry in open rifle pits to the front, sides, and rear. Also, the emplacements had screened loopholes to fend off thrown hand grenades. Some infantry were concealed in foxholes in the ground, under trees, or even in hollowed out logs, while others simply waited in the jungle, where they were heavily camouflaged. Snipers in the tall coconut trees or in concealed positions were a menace.

The Australian advance also moved slowly. The 16th Brigade had lost half its number through battle casualties and sickness and by the end of November was suffering from fatigue, malnutrition, and a shortage of supplies. In early December, General Vasey diverted his reserve brigade to Gona to relieve the exhausted 16th Brigade, which had lost 85 percent of its original complement and could no longer function in an offensive role. The eastern and southern parts of the front were bogged down by mid-December, although the Australians were progressing on the western flank around Gona. Here, the Australian 25th Brigade had pushed the Japanese into swamps and then, exhausted by heavy fighting, the brigade was relieved by the fresh 21st Brigade under Brigadier I.N. Dougherty. This move tipped the balance around Gona to the Australians, who entered the town on December 9, while the battle raged around Buna.

To relieve the stalemate around Buna, the main front, Blamey brought in his remaining 18th Brigade battalions from Milne Bay along with a squadron of M3 Australian-crewed U.S. light tanks, since the Allied attackers at Buna had extremely limited artillery. Only the short 25-pounder and a couple of 105mm howitzers with limited ammunition were available to penetrate the reinforced Japanese bunkers there. Due to the dense vegetation, it was difficult to effectively spot where their rounds were landing. The U.S. 105mm howitzer was a great bunker buster; however, the absence of shipping and the terrain necessitated using mortars. The M3 light tanks, although armed with a 37mm turret gun and .30-caliber machine guns, could still only move properly on relatively cleared, firm ground. All the tanks were knocked out in the first four days, although the Australian infantry was through the Japanese front in two places on Buna’s eastern sector.

Further tank reinforcements arrived, and the hardcore Japanese resistance east of Buna was broken at the expense of just over 50 percent of the 18th Brigade as battle casualties. In late December the Americans, under Lt. Gen. Eichelberger, took Buna, linking up with the Australians on January 2, 1943, and leaving the Allied force available to concentrate on Sanananda Point between Buna and Gona.

The hard fighting in the early stages had so exhausted the Australian units that progress on this part of the front was impossible until the depleted ranks of the 18th Brigade had been freed from around Buna and the U.S. 163rd Regiment, 41st Division was brought forward. There were literally no other intact Australian infantry formations in Papua.

Consequently, Vasey had to wait until the end of December before he could move across to the Sanananda Trail and drive toward the coast with the 163rd Regiment and 18th Brigade, the latter reinforced by 1,000 fresh men. The Allied attack began on January 12, 1943, and made slow progress, gradually bearing down on Sanananda with a two-pronged thrust, one from the northeast along the coast, and the other from the track to the southeast. The Japanese tried on several occasions to reinforce Sanananda, but most convoys were strongly attacked by Allied aircraft, and only a few hundred men were landed.

Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo decided in early January that Papua would have to be abandoned, and on the 13th the Japanese at Sanananda began to collect their forces at suitable embarkation points along the coast. By January 22, the battle for the Buna-Gona-Sanananda beachhead was over. Japanese losses at Sanananda were at least 1,600 dead with many more missing. At Sanananda, 1,400 Australians and 800 Americans were killed or wounded. For the entire Papuan campaign the cost was staggering for both sides. The Allies had a total of 8,546 killed or wounded, of whom 5,700 were Australian. The Japanese had committed approximately 18,000 men to the campaign, of whom 6,200 were lost after the withdrawal from the Owen Stanley Range. Between November 19, 1942, and January 22, 1943, at least 8,000 more Japanese were killed or wounded. Malaria produced 27,000 medical casualties among all combatants, largely because of the shortage of quinine, which was produced mainly in Japanese-held Indonesia.

The Australian 7th and American 32nd Infantry Divisions were severely mauled. Australian militia battalions had suffered grievously. The American 41st Infantry Division was exhausted as well. Both American infantry divisions would require six to 12 months of reinforcement and refitting to prepare for the next series of battles, while the Australians would defend against further Japanese incursions into the Markham River Valley to the west.

After the disastrous Philippine campaign of early 1942, General MacArthur needed a victory in Papua so the American leaders would regain confidence in his military prowess. The U.S. Army learned a lot from the Papuan campaign of 1942-1943, but at a high cost. It was clear that in the summer of 1942, U.S. Army units were insufficiently trained in contrast to the Australians, many of whom had served in the Middle East.

After the victory in Papua in January 1943, MacArthur decreed that there would be “no more Bunas!” According to the Australian official history, “The primaeval swamps, the dank and silent bush, the heavy loss of life, the fixity of purpose of the Japanese, for most of whom death could be the only ending, all combined to make the struggle so appalling that most of the hardened soldiers who were to emerge from it would remember it unwillingly as their most exacting experience of the whole war … a ghastly nightmare.”

Jon Diamond is a frequent contributor to WWII History. His book, Stilwell and the Chindits: The Allied Campaign for North Burma 1943-44, was released by Pen & Sword.

It’s actually Kokoda ‘Track’ not ‘Trail’